Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Pehr Forsskål – brilliant Swedish scientist

Centered around him was a group of scientists, who were often called his disciples, or even ‘apostles’, as he sent them on travels around the world to collect plants and animals. Among the most prominent of these disciples were Pehr Forsskål (1732-1763), Daniel Solander (1733-1782), Carl Thunberg (1743-1828), Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), and Adam Afzelius (1750-1837).

He had just received a letter, which had been sent from Yemen the previous year by one of his disciples, Pehr Forsskål. The letter contained a number of items, including a twig from the balsam tree of the Bible, sent by Forsskål to his master. Sadly, Forsskål died of malaria shortly after the letter was sent. He was an exceptionally gifted scientist, and his untimely death was a huge loss to Sweden and to the academic world.

In scientific literature, Forsskåls name appears in many different forms, including Forsskaal, Forsskal, Forskål, Forsskåhl, Forskåhl, and Forskaol, and his Christian name as Pehr, Per, Peter, Petter, and Petrus. In this paper, I use Pehr Forsskål, which is the most commonly used form in Sweden.

Forsskål was born in Helsinki on January 11, 1732, the youngest son of clergyman Johann Forsskål. His mother died, when he was only 3 years old. In 1741, the family moved to Uppland, where his father was appointed.

In those days, it was customary for sons of prominent citizens to start university studies at an early age. In 1742, when Pehr was only 10 years old, he and his two brothers were enrolled at the University of Uppsala. However, their father’s income was only sufficient to pay for two of the sons, and as Pehr was the youngest of the three, he was instead taught by the father himself, in subjects like theology, philosophy, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. Pehr was indeed an exceptionally gifted person. When he was only 13 years old he was able to write letters in Hebrew.

In 1751, due to his “outstanding knowledge”, he was granted a scholarship for 7 years of studies, 5 years in Uppsala, and 2 years at a European university, of his own choice. In those days, you studied broadly, and Pehr’s subjects were theology, philosophy, and natural sciences. The same year he passed his grade in theology.

Forsskål studied various natural subjects, including the metamorphosis of insects, and his interest in natural sciences made him an acquaintance of Linnaeus, whom he quickly came to admire.

In 1753, at this university, Forsskål began studies of philosophy and oriental languages. In 1756, he graduated as a doctor of philosophy, defending a thesis named Dubia de principiis philosophiæ recentioris (’Doubts about the principles of newer philosophies’), in which he was criticizing Wolffianism, which in those days was the most popular philosophical doctrine. The same year he returned to Uppsala, where he wanted to study economics, agriculture, and natural sciences.

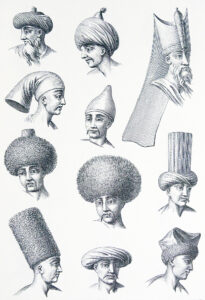

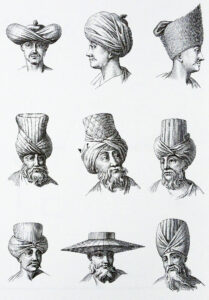

At this time, the ruling party in Sweden was Hattene (’The Hats’), thus named because of the hats that the members of this party were wearing, as opposed to members of another party, Mössorne (’The Caps’, or ‘The Berets’).

Censorship was widespread – a state which Forsskål found extremely unsatisfactory. In May 1759, he submitted an application to dispute on a paper of his, called De libertate civilii, which, simultaneously, was to be published in Swedish, titled Thoughts about civil freedom. This paper contained permissive thoughts, requesting political and economical freedom, as well as freedom of press.

To write a controversial paper in Latin is one thing, but to publish it in the common language was an entirely different matter, unheard of in those days. The day the paper was printed, Forsskål himself distributed the 500 Swedish copies among the students of the university.

When members of ’The Hats’ read the paper, they instantly forbade distribution of it, but it was already too late. Many people got acquainted with these new thoughts, and the paper contributed strongly to the abolition of censorship, which took place in 1766. However, Forsskål died several years prior, and thus didn’t experience the result of his efforts.

Until then, a greater part of this information had been rather accidental and often highly subjective descriptions, supplied by seamen and other traders. Now the time had come to make a more thorough description of the World – not only to promote trade and exploitation of natural resources, but also to increase theoretical and scientific knowledge.

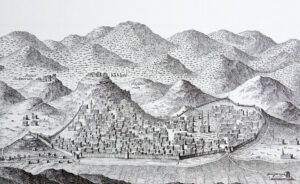

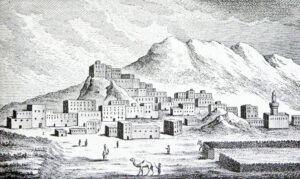

Danish King Frederik V (1723-1766) and his minister of foreign affairs, German Count Johann Hartwig Ernst von Bernstorff (1712-1772), were both eager patrons of this achievement of new knowledge. In 1756, Professor Michaëlis in Göttingen sent a letter to his fellow-countryman in Copenhagen, suggesting that the Danish king should send an expedition to Yemen in southern Arabia, since ancient times known as the legendary Arabia Felix (’Happy Arabia’) – a symbol of the unobtainable ’Land of Happiness’. In all probability, this epithet was bestowed on Yemen solely due to its remoteness.

In his suggestion, Michaëlis wrote the following: “Nature in this land is still rich in gifts, which are unknown to us. Its history goes back to ancient times; its dialect is different from Western Arabic, and as the latter form of Arabic, which is the one we know, has hitherto been the best aid to describe Hebrew, what light might be thrown on the text of The Bible – the most important book of ancient times – if we were to learn the eastern dialect of Arabic as well as the western?”

King Frederik approved of the idea. Initially, the plan was to send a researcher, accompanied by a servant, to the Near East, travelling on board a Danish merchant ship. His task was to explore the Yemen and other countries, primarily to make it possible to interpret The Bible with new eyes. Secondly, he was going to carry out studies of geography and natural sciences.

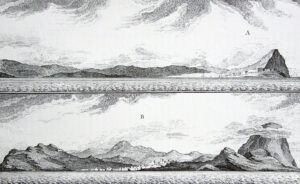

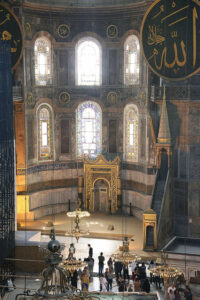

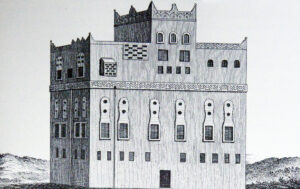

As time went by, Michaëlis succeeded in convincing Bernstorff that all these tasks would be too much for one person to carry out. It was agreed that four scientists should go to Constantinople (today Istanbul) on board a Danish ship, and from there travel on their own to Egypt, and along The Red Sea to Yemen. The research subjects were oriental languages, ethnography, medicine, geography, cartography, astronomy, botany, and zoology. An artist should accompany the scientists, besides an orderly to service these five men. This plan roused a stir in European academic circles.

Like a majority of nobles in those days, von Haven was very self-centered and extremely conscious of his honour. To carry out studies of oriental manuscripts prior to the expedition, he spent a couple of years among Arabic Maronites in Rome – paid by the Danish king. He was also supposed to learn Arabic here, but at the start of the expedition his knowledge of this language was rather limited.

As it turned out, Denmark only had few persons in the natural sciences with the necessary qualifications for the expedition. When corresponding with Bernstorff, Michaëlis as well as Linnaeus praised Pehr Forsskål, Michaëlis because of his knowledge of Hebrew and other oriental languages, Linnaeus because of his qualifications in natural sciences.

Bernstorff was soon convinced that Forsskål should become a member of the expedition. Forsskål’s dispute with ’The Hats’ had made it extremely difficult for him to obtain an academic career in Sweden, so when he, in October 1759, received Bernstorff’s offer to participate in a Danish scientific expedition to the Near East, he grabbed this opportunity with pleasure. His tasks were to collect and describe as many plants and animals as possible, and to note their utilization among the local inhabitants, if any. It was of special importance to find as many species as possible of the plants mentioned in The Bible.

According to instructions from Danish Professor Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (1723-1795), Forsskål also had to carry out marine-biological studies, including subjects like phosphorescence, fishes, molluscs, and corals.

However, Forsskål did not hide his light under a bushel. To participate in the expedition, he demanded a Danish professorship. He also demanded to become the leader of the expedition – a title, to which von Haven considered himself the obvious choice. Because of these two learned gentlemen’s dispute, Bernstorff chose to make all five members of the expedition equal – something which was unheard of in those days.

Forsskål also demanded that when the expedition had been successfully carried out, he was to receive pension from the Danish government, and that he could reside anywhere in Europe. It must have taken Bernstorff some swallowing to accept this demand, but it seems that he was hard up for suitable scientists.

Forsskål was a great admirer of Linnaeus, so he applied for permission to send duplicates of collected plants and animals to Uppsala. This was flatly denied, referring to the fact that this was a Danish expedition, and Denmark alone should benefit from the achieved results. All collections were to be sent directly to Copenhagen, from where any duplicates later could be sent to Linnaeus or other scientists in Europe.

Forsskål was furious, but accepted this order. Later, however, he started sending letters to Uppsala, containing a system of numbers that only he and Linnaeus had knowledge of. In this way, his mentor could obtain descriptions, getting around the Danish bönåser (‘dabblers’) – referring to his employers in Copenhagen. His criticism of Kratzenstein was completely unreasonable, as his marine-biological instructions were far ahead of their time.

As geographer and cartographer on the expedition, Michaëlis recommended a German, Carsten Niebuhr (1733-1815). His primary task was to determine latitude and longitude of locations visited by the expedition, and to produce maps from these measurements. Furthermore, he was supposed to research in climate and human population issues.

He made a good impression on Bernstorff, and as the latter had had a number of bad experiences with von Haven, who had squandered the king’s money during his stay in Italy, Bernstorff made Niebuhr the economist of the expedition – which made von Haven furious.

Niebuhr was younger than the other members, and when he, like von Haven and Forsskål, was offered a professorship, he humbly declined. Instead he got the title of engineer-lieutenant (corresponding to a surveyor today).

The tasks of Danish member Christian Carl Kramer (died 1764) was to research scientific and everyday medical treatment in the Arabian countries. Furthermore, he had to assist Forsskål during his collections.

Kramer’s knowledge was limited, and Forsskål doubted his competence. Instead, he suggested a disciple of Linnaeus, Johann Peter Falck. Forsskål wasn’t exactly diplomatic, and his impetuous behaviour caused Bernstorff to decline his suggestion. Furthermore, he didn’t want the expedition to hold more Swedes than Danes.

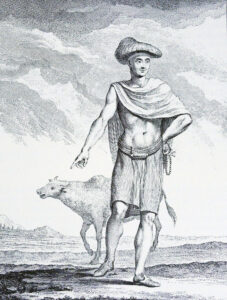

The primary task for German artist Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind (1728-1763) was to draw plants and animals, which were too fragile to conserve (including medusa). Furthermore, he was supposed to illustrate architecture, people, and other subjects, which the other members of the expedition found interesting.

The servant was a Swedish dragoon, named Berggren (died 1763). His knowledge of horses was beneficial to the expedition in Yemen, where he cured one of Emir Bahr’s horses. Apart from that, nothing is known about him.

That winter was characterized by repeated strong gales from north-west, and each time the ship tried to round the northern tip of Jutland, Skagen, it had to return to the town of Elsinore. As von Haven suffered much from seasickness and other agonies on board, he applied for permission to go overland to Marseilles, which was granted. In Marseilles, he would again join the party.

On March 10, Grønland once again left Elsinore, this time passing Skagen without problems. However, a strong southerly gale now blew the ship all the way up into Icelandic waters – after which it was dead calm for days.

Despite all these delays, Forsskål and Niebuhr were full of optimism and didn’t waste their time. Niebuhr practiced locating positions, using his so-called astrolabium, while Forsskål caught sea creatures in a net through the gun ports. He tried to solve the mystery of phosphorescence. By sieving sea water through ever finer cloth, he was able to conclude that the water finally stopped phosphorizing – which meant that the light did not stem from the water itself, but from a living organism in it.

The ship reached Marseille on May 13. Forsskål went on several botanical collecting trips around the city, and he had time to visit colleagues in Montpellier.

By now, von Haven had rejoined the party, and during a banquet on board the ship it quickly became obvious that the composition of the expedition members was very unfavourable. During the banquet, various subjects were discussed, including the elected heir to the throne in Sweden. Von Haven’s pronounced lack of diplomacy caused him to insult the Swedish chief court official, Tessin. Forsskål retorted, and the quarrel between the two eventually caused von Haven to fling out these pithy words: ”Kiss my arse!” From this day, there was cold air between the two learned gentlemen.

On several occasions during the journey across the Mediterranean, Grønland’s crew made preparations to confront English war ships who demanded to inspect the Danish merchant ships, which was refused by the captain. However, direct actions of war were avoided.

On June 5, enemy ships were spotted in the distance, and on June 6, the crew on Grønland was busy, preparing defence of the ships. While this took place, Niebuhr calmly stood on deck, using his astrolabium and his telescope to observe and describe a Venus Passage. However, he complained that the ship was shaking too much to make precise observations.

The ships called at the port of Malta June 14-20. On this island, Forsskål’s and Niebuhr’s field work started in earnest – almost half a year after the start of the expedition. Forsskål made a list of encountered fossils, 11 molluscs and 3 sea urchins. He does not mention the highly interesting mammal sub-fossils, including dwarf elephants and hippos, which can be found among the rocks on Malta – presumably he didn’t encounter them.

His Florula Insulæ Melitæ includes 78 wild and 9 cultivated plant species from the island, of which he is still author of the genus Pteranthus, and of 7 species: Pteranthus dichotomus, Urtica dubia, Coronopus squamatus, Orobanche crenata, Halophila stipulacea, Vulpea fasciculate, and Polypogon semiverticulatus.

Following a visit to the San Giovanni Church in Valletta, he complained that a relic in this church, which is supposedly a thorn from the Crown of Thorns of Christ, could not stem from Rhamnus spinosa (today named Paliurus spina-christi), and, therefore, had to be a forgery.

He described a black and rose-coloured bird, which he thought was a thrush, naming it Turdus seleucis. He was told by locals that, according to the Koran, it was prohibited to kill this bird, because it was able to eat more than 10,000 grasshoppers a day. However, the bird is not a thrush, but the rosy starling, today named Pastor roseus.

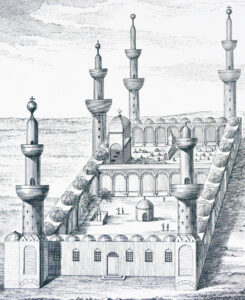

On their way north towards Constantinople (today Istanbul), Forsskål also went ashore on several plant collecting trips. Finally, on July 30, the ship called at the port of Constantinople, where the expedition members were housed by von Gähler, the Danish envoy. Their stay in the city was prolonged by Niebuhr’s illness, but Forsskål didn’t waste his time, making several trips to collect specimens.

In the beginning of September, Niebuhr had almost recovered, and the members left Constantinople on board a Turkish ship, bringing female slaves to Alexandria. Von Gähler had advised them to wear oriental dress, as he thought this would help them to carry out their work, unchallenged by the locals. On board, Forsskål caught animals in the sea water through a port-hole, and his activities were noticed by some slave girls, who were accommodated in the cabin above. He had fun exchanging sweets and fruit with the young ladies.

However, Kramer was present and noticed the purchase, and later he referred the incident to the other members who were deeply alarmed and wrote a letter to Bernstorff, in which they urged him to dismiss von Haven. The answer took many months to arrive, but was very clear: According to the royal instructions, the entire party must stay together, and disagreements had to be solved with tolerance.

Supposedly, von Haven’s purchase was an act of desperation, as he had several opportunities to poison the other members. However, it never happened.

Collecting around Cairo was not without risk, and on several occasions Forsskål was attacked by robbers. His guide suggested that Forsskål should stay in the city, while he and his assistants, for a small fee, would bring back plants and animals, making it possible for Forsskål to study and describe them at his leisure. This arrangement worked to everyone’s satisfaction.

In town, Forsskål visited Greek apothecaries to describe which plants, animals, and minerals their medicine stemmed from. He collected information about 565 types of medicine, noting their name in Latin as well as in Arabic, but unfortunately not always their usage.

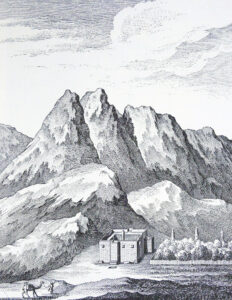

While Niebuhr and von Haven travelled to the Sinai Peninsula to visit Jebel el Mokateb and the Santa Catarina Monastery, Forsskål remained in Suez with Kramer to nurse Baurenfeind, who was ill. In this way, he could avoid accompanying von Haven, whom he detested and despised. However, he later regretted his decision, as time went by, and he began to get bored.

A visit to the Catarina Monastery could only be made with due permission from the Bishop of Cairo, but he had gone to Constantinople, after the expedition members had applied for a letter of introduction, without issuing this important document. For this reason, von Haven and Niebuhr were refused permission to enter the monastery.

Forsskål informed the pilgrims that a solar eclipse would occur on October 17. As it turned out, he was correct, causing many on board to regard these foreigners as wizards. Sick people were brought to them to be cured, and Forsskål gave many useful and practical recommendations.

On board were also rich Turks, accompanied by their harem. Niebuhr discovered that the bathroom of these ladies was just next door to the cabin of the expedition. He writes: ”Until our departure from Suez I had scarcely seen the naked face of a Muslim woman,” but through a crack in the wall “(…) I saw more.”

After a voyage of 20 days, the boat anchored at the port of Djidda. In this town, the party had to wait until December 13, before they could continue their journey southwards on board a smaller boat, a so-called tarrad. For once, it seems that Forsskål didn’t make any collections, but it must be admitted that he had already sent numerous collections to Copenhagen. Some speculate that he suffered from homesickness in Djidda.

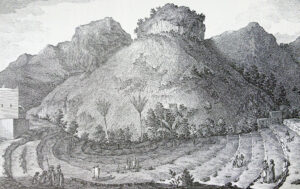

Two weeks later, the party arrived at the port of Al Luhayyah (Lohaja), northern Yemen. Here they encountered widespread hospitality, and for all of them the happiest time of the entire journey occurred. Forsskål, who was a linguistic genius, learned the local dialect in no time, and for weeks he and Niebuhr rode on donkeys through the Coffee Mountains, which stretch north-south along the coast of Yemen, some distance inland.

They visited one friendly village after the other, and in a crumbling house, near the town of Bayt al Faqih, Forsskål studied termites, which he had not encountered before.

Instead of continuing their journey towards the capital, San’a, in the mountains, the party decided to travel to the sea port of Al Mukha (Mocha). As it turned out, this was the most serious mistake on the entire expedition. The cool air in the mountains around San’a might have cured the disease, while the humid air on the coastal plain – where Forsskål measured temperatures as high as 39 degrees Centigrade – made it worse. The party, however, thought that travelling in the mountains would be too strenuous for the sick.

In Mocha, their troubles started in earnest. The Dola, the Turkish governor of the city, was very suspicious of these foreigners, and he demanded them to open the boxes, which contained their collections. Forsskål writes about this event: “Emir Farhan had already written to the Dola that we were learned travellers, who did not bring anything liable to customs duty, and that we only needed protection. When the Dola as usual went to the customs building early in the morning, some of our party went out to greet him. He was a weak old man, supported by his subordinates. The young tradesman Ismael told him that we were the same Franks, whom Emir Farhan had recommended. He ordered Emir Bahr, the ship inspector, only to inspect the bagage and leave it our quarters, as is the custom with everything not liable to customs duty. Soon another order was given that the Dola wanted to survey the inspection. As bad luck would have it, the boxes with natural objects were first inspectes. This happened without mercy, and fragile conches were thrown away as junk without any value. Iron spikes were thrusted through the boxes, and the staff made faces about such items, which were considered unworthy to bring about at a great cost. On purpose, the staff broke large conches and other items in the box. Later, another box was opened, which contained jellyfish, which had not dried completely, and emitted a bad smell in the entire room. And to make things worse, the box contained a bottle with a snake in alcohol. This caused a great sensation, and by now the Dola and his staff regarded us as people who travelled around with illegal things. It was ordered that our things should be thrown into the sea, and we were not permitted to stay one more night in the city. I took out the bottles containing fishes, and showed him that they were not suspicious, and we were not suspicious, only keeping such things to be able to show rarities from far away places in our country. To no avail. The anchors, which contained alcohol, broke due to mishandling, and some of it ran out. This smell was even worse for the Muslims who hate alcohol. This was more than enough to make the entire city against us. At 11 o’clock, the customs building was closed, and the Dola went home, embittered. Our things, which were kept in the house that we were supposed to stay in, were thrown out, and the gate was closed. The boxes, which had been inspected, were placed in the street in front of the customs building, where the mob fingered the things, declaring that we were sorcerers who wanted to poison the entire population with unclean things. Ismael had disappeared, and when we went to his house, a subordinate Dola abused us with foul words. All this was very trying indeed.”

The party ended up paying 50 Ducates as a bribe to get their boxes back. In a letter to Linnaeus, Forsskål wrote: “Later, we made peace with the stupid governor, and their opinion about us improved somewhat.”

Von Haven went from bad to worse and succumbed to the illness on May 25. By now, Forsskål was desperate, and after von Haven’s funeral, the party left Mocha as quickly as possible. On June 9, they travelled inland, and despite the difficult conditions, Forsskål continued to carry out botanical collections.

In the town of Torba, his Arab donkey driver committed burglary in the local mosque. Forsskål managed to prevent the donkey from entering the mosque. Later, he wrote, ”which would have been the only instance in the entire Muslim World History.” Again, his fluent Arabic carried the expedition unscathed past this incident.

Slowly, Niebuhr’s condition improved. Forsskål wished to climb a mountain, Jabal Saber, which, at an altitude of 3,007 m, has a very interesting flora, but he had huge difficulties obtaning permission to do it.

However, his plans were cancelled, as he, on June 28, suddenly broke down with a high fever. The other members of the party tied him to a dromedary, and, suffering tremendous hardships, they arrived at the town of Yarim (Jerim) on July 5. Here, the mob threw stones at them, and only by paying a huge sum they succeeded in renting a house, in which they could nurse Forsskål. However, his condition worsened, and on July 11, he succumbed to the fever. With great difficulty, Niebuhr managed to obtain a place to bury him, but the grave was plundered shortly after the burial, and today the location of Forsskål’s grave is unknown.

By now, all the members had a fever, and, at a forced speed, they continued towards Mocha, reaching the city on August 5. Here they were able to board a British ship, bound for Bombay (today Mumbai), India. Kramer, Baurenfeind and Berggren were now so weak that they had to be carried on board, and only Niebuhr was able to walk. After a few days of journey, Baurenfeind and Berggren died, and their bodies were lowered into the sea. In Bombay, Niebuhr slowly recovered, but Kramer passed away in February 1764.

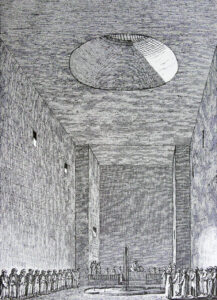

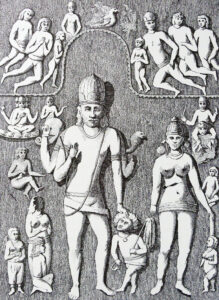

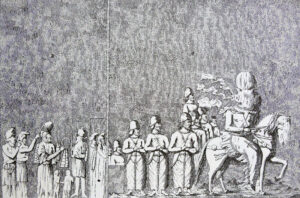

While in Bombay, Niebuhr made an excursion to a famous Hindu temple on the island of Elephanta, in which a marvellous statue, called Trimurti, or Mahesamurti, shows the three aspects of the god Shiva: the destructive one, called Bhairava, the preserving one, and the feminine one, Shakti, locally called Vamadeva.

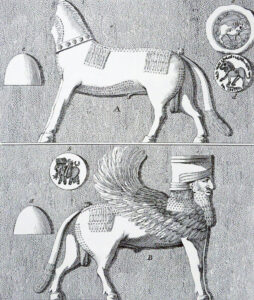

He also visited Gujarat, before travelling by ship from Bombay to Mascat, Oman, in December 1764. From here, he was able to go to Bushire in Iran, and in spring 1765 he spent a month in the ruined city of Persepolis, copying the numerous cuneiform writings on the pillars.

Then, joining caravans, he continued overland to Baghdad and Mosul in Iraq, and on to Halep (Aleppo), Syria. In 1766, he made two side trips to Cyprus and the Palestine, before travelling through Turkey to Constantinople. Here he was housed by von Gähler, who had long thought him dead.

Finally, Niebuhr rode overland across eastern Europe, reaching Copenhagen on November 20, 1767, almost seven years after the start of the expedition.

Undeterred by these events, Niebuhr now arranged Forsskål’s zoological and botanical collections and notes. The herbarium alone comprised about 1750 sheets (more than 2000, if you include algae). When nobody showed the slightest interest in publishing the material, Niebuhr himself published it in 1775 and 1776, in three volumes.

The zoological collections are described in a volume, named Descriptiones Animalium Avium, Amphibiorum, Piscium, Insectorum, Vermium; quæ in itinere orientali observavit Petrus Forskål, while the botanical results are presented in a volume, named Flora Ægyptiaco-Arabica sive descriptiones Plantarum quas per Ægyptum Inferiorem et Arabiam Felicem, detexit, illustravit Petrus Forskål.

The third volume, Icones rerum naturalium, quæ in itinere orientali dipingi curavit Petrus Forskål, contains 43 of Baurenfeind’s illustrations from the expedition, namely 20 plant species, one bird, and the rest marine animals, of which the major part were new to science. The text in this volume was supplied by botanist Johan Zoëga (1742-1788), who presumably also assisted Niebuhr editing the other two volumes.

Within the zoological field, Forsskål was a pioneer in marine biology, and in the study of bird migration. At Istanbul, Alexandria, and Lohaja, he noted the arrival and departure time of several migrating bird species. He described 17 bird species and 13 species of reptiles (tortoises, lizards, and snakes).

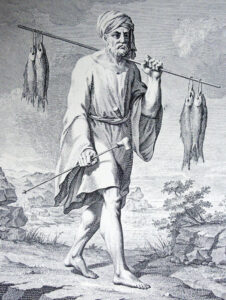

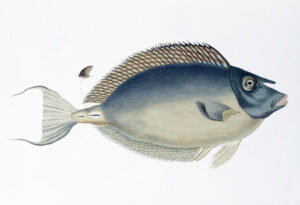

However, his most important zoological contributions concern fishes and molluscs. No less than 151 species of fish were described during the expedition. Forsskål invented a unique method to conserve the collected fishes, so that they wouldn’t rot. He simple cut open the fish, removed guts, meat, and most of the bones, after which he placed the skin, including the head, tail, fins, and sometimes part of the vertebra, in the strong sunshine, under pressure. After being dried, the fishes could be kept between sheets, just like pressed plants.

Altogether 99 skins from the Red Sea, belonging to 60 species, are still present in the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen. This collection is popularly labelled ’Forsskål’s Fish Herbarium’. Today, 52 of the species still carry Forsskål’s name as author, although 48 have been moved to other genera. 44 species from the Red Sea, and two genera, Abudefduf and Siganus, were named using Arabic terms. In Arabic, abu means ‘father’ and def ‘side’, while duf is a plural appendix, expressing something which is intense. Thus, Abudefduf means ‘the father (i.e. the head) of prominent sides’. The body of several species in this genus is heavily striped.

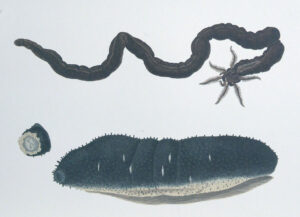

The term vermium in the title of the book denotes numerous animal groups, which, in those days, were considered to be related to each other: molluscs without shell or skeleton, molluscs with shell, molluscs with a ‘soft’ skeleton, including sea salps and coelenterates, and corals.

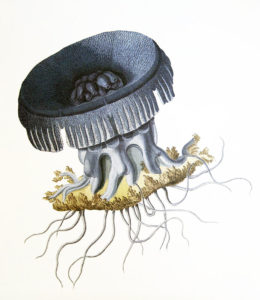

Within these groups, Forsskål described numerous new species. He caught the drifting gilled gastropod Ianthina, and described the development of the larvae of this group, which was hitherto unknown. He discovered a new group of keeled marine gastropods, which are pelagic, and an entirely new group of animals, the sea salps, of which he described no less than 10 species. He also described numerous new medusa and no less than 26 species of corals.

Among arthropods, such as spiders, insects, and crustaceans, Forsskål described 62 species, including a locust, and a species of gall wasp, which plays an important role in the pollination and ripening of the fig fruit. 53 species were briefly mentioned.

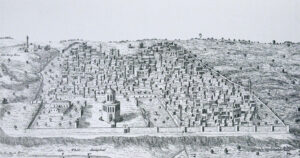

The drawings below were made by Baurenfeind and published in Icones rerum naturalium.

In Flora Ægyptiaco-Arabica, a detailed description of more than 800 species can be found, many of them also provided with their Arabic name. In 1790, in his volume Symbolæ Botanicæ, Danish botanist Martin Vahl (1749-1804) gives a detailed description of Forsskål’s entire botanical collection. Since then, the collection has been revised several times, in 1915-1918 by Danish botanist Carl Christensen (1872-1942), who called it ”the most important treasure of our botanical museum,” and in the 1980s by British botanists Frank Nigel Hepper (1929-2013) and John Richard Ironside Wood (born 1944).

From the described plants, Forsskål collected no less than six sets of seeds. French botanist Antoine Banal had given him the idea to send seeds to six important universities in Europe: Copenhagen, Uppsala, London, Paris, Göttingen, and Montpellier. In this cunning way, his mentor Linnaeus could obtain, if not the plant itself, then at least its seeds – and, what was important, with Bernstorff’s acceptance.

During his long stay in Lower Egypt, Forsskål acquired a thorough knowledge of the adaptation of the plant species to the annual alternation between dry season and rainy season. He was the originator of several completely new theories. In his opinion, the flower is a modified shoot, in which the petals are modified leaves – a theory which the poet Johann Goethe was accredited with many years later.

Furthermore, Forsskål was a pioneer in plant geography. He drew the conclusion that a geographical area can be characterized by its composition of plant species. Again, another person was accredited with this new theory, namely Alexander von Humboldt, in 1805.

Linnaeus had urged his disciple to make a special effort to find the famous Mecca balsam tree of The Bible, which was unknown in those days. Today, we know that Mecca balsam, as well as myrrh, is resin from trees of the genus Commiphora, of the torchwood family (Burseraceae). Mecca balsam is from Commiphora gileadensis (syn. C. opobalsamum), which is a native of southern Arabian mountains, whereas myrrh is from Commiphora myrrha (syn. C. molmol), which is from Somalia and Ethiopia. These two products, and resin from Boswellia sacra, which is utilized as incense, were very important trading items during more than 3,500 years, and numerous caravans travelled from Southern Arabia to the coasts of The Mediterranean.

In April 1763, Forsskål and Niebuhr were working in the Coffee Mountains, when Forsskål, near the village Öude (Uday), noticed something glinting in a flowering tree. As it turned out, the glinting was caused by the reflection of sunshine on resin on the tree. After a short inspection, Forsskål realized that he had found the Mecca balsam tree. As quickly as possible he sent a letter to Linnaeus, containing a flowering twig from the tree. The letter, however, didn’t reach Sweden until September 1764. Naturally, the flowers had withered by then, but nevertheless Linnaeus, from the twig, and from Forsskål’s enclosed notes, was able to describe the species, naming it Amyris opobalsamum.

Forsskål described many other new plant species in Yemen, including a very low member of the dogbane family (Apocynaceae) with a very fat trunk, which he named Nerium obesum (today called Adenium obesum), a member of the arum family with a yellow spathe, Arum flavum (today Arisaema flavum), a species of fig, Ficus palmata, two legumes, Lathyrus spectabilis (today Clitoria ternatea) and Indigofera spicata, a species of primrose, Primula verticillata, and two orchids, Orchis aphylla (today Habenaria aphylla) and Orchis flava (today Eulophia streptopetala var. rueppelii).

In Yemen, like in Egypt, Forsskål made notes about the utilization of plant species as traditional medicine etc. A single example is a species of the birthwort family, Aristolochia sempervirens (today A. bracteolata), whose crushed leaves were used as a remedy to heal wounds, and to treat snake bites. Even today, this species is a remedy in Yemen for treatment of snake bites.

The drawings below were made by Baurenfeind and published in Icones rerum naturalium.

During the 1770s, there were plans to publish Forsskål’s diary, but they were not carried out. As a matter of fact, for almost 200 years it was believed that the diary had disappeared, until a copy was found in the university library in the town of Kiel, northern Germany. It was published in Swedish in 1950, titled Resa till lycklige Arabien. Petrus Forsskål’s dagbok 1761-1763 (‘Journey to Happy Arabia. The diary of Petrus Forsskål 1761-1763’).

Niebuhr’s diary and other notes were published in German in 3 volumes, in 1774, 1778, and 1837, respectively, titled Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern (‘Description of Arabia and other nearby countries’).

Niebuhr’s greatest achievement was in cartography. For the first time, Malta was precisely placed on the Mediterranean map. His map of The Red Sea was so detailed that European ships, by following it, without problems could navigate waters, filled with reefs, all the way up to Suez. His copies of the cuneiform writings on the pillars of Persepolis were so precise that they provided a basis for the deciphering of the script in 1802.

Von Haven’s notes are kept in The Royal Library in Copenhagen, comprising two volumes. One is a travelogue, the other contains a list of acquired manuscripts, copies of inscriptions, and two short lists of translated words, one Arabic-Danish and one Arabic-Italian (the latter from his stay in Rome).

Prior to the expedition, the library’s collection of Near-Oriental manuscripts consisted of rather accidental purchases and gifts, but with von Haven’s competent purchases, the library was now in a much stronger position in this field. His diary was published in Danish in 2005, titled Min Sundheds Forliis. Frederik Christian von Havens rejsejournal fra Den arabiske Rejse 1760-1763 (‘The loss of my health. Frederik Christian von Haven’s travelogue from The Arabian Journey 1760-1763’).

Baurenfeind’s drawings were precise and realistic.

Niebuhr notes: ”(…) through his mingling with the common people during his botanical trips (…) he was the one of our party, who had best learned Arabic and its various dialects (…) He was born, so to speak, to participate in a journey to Arabia. He didn’t easily get dissatisfied, when comfort was lacking. He instantly got used to live according to the local ways, and this is necessary, if you want to travel in Arabia with benefit and pleasure.”

Forsskål was utterly cool to hardships and dangers, and during his research trips in Egypt he was confronted by robbers on several occasions. He also assisted Niebuhr, when the latter was making measurements of the Giza Pyramids, but here his stubbornness caused quite a few problems. A young Bedouin offered to be their guide, which was declined by Forsskål. This made the young man so angry that he knocked Forsskål’s turban off his head.

However, instead of reacting, Forsskål calmly said to the young Bedouin’s two companions: ”You Bedouins, among your fellow-countrymen it is believed that the Franks (Europeans) at any time are safe under your protection. I have travelled among your fellow-countrymen. If you allow your companion to rob me, I am going to tell my fellow-countrymen that among you you find neither faithfulness or faith.”

His speech had the effect that the young Bedouin’s companions did not allow him to rob Forsskål. Instead, he turned towards Niebuhr and tried to grab his precious astrolabium. This made the quiet German so upset that he pulled at the Bedouin’s clothes, which caused him to tumble off his horse. The young man got so furious that he pulled his pistol and pointed it at Niebuhr’s chest. Niebuhr later wrote: ”I must admit that I thought I was going to die. But, presumably, the pistol was not loaded.” The Bedouin was calmed by his companions and finally accepted a small sum as compensation from Niebuhr.

Forsskål showed great versatility in his knowledge and interests. Likewise, his nature was indeed complex. He was friendly and amiable towards the locals on most occasions, and towards persons whom he respected, such as Niebuhr, who possessed the same virtues as himself.

On the other hand, he could be extremely arrogant and condescending towards persons, who showed signs of weakness, for instance the lazy Kramer and the indolent and timid von Haven, who spoke only a little Arabic and, furthermore, didn’t like the Arabs and their way of life. This passage from Forsskål’s letter to Linnaeus, following von Haven’s death in Mocha, shows his implacability after his controversies with the deceased, coupled with an ample dose of cynicism: “One of our party, Professor von Haven, died here on May 25, and his departure made travelling so much easier for the rest of us. His disposition was rather troublesome.”

Forsskål had asked Linnaeus to name a plant after him. Linnaeus chose a plant of the nettle family, which Forsskål had named Caidbeja after the town of Caid Bey, where he first found it. Linnaeus renamed it Forsskaolea tenacissima, and his description also contained the adjectives hispida, adhærens, and uncinata. These four words mean something like stubborn, stiff, obstinate, and bent.

When Niebuhr read the description, he was infuriated, regarding it as a scorn towards the deceased. However, this was hardly Linnaeus’s intention, as he regarded Forsskål as one of his most gifted disciples, but, presumably, he found his characterization of the temperamental and somewhat obstinate Forsskål very apt. In reality, the word tenacissima can also be translated as determined or energetic!

Niebuhr characterized his friend as follows: “Forsskål was the most learned person of our party, and had he returned home alive, he would have been the most learned person in all of Europe. He was hard-working, and he despised all dangers, hardships, and renunciations. His shortcomings were his fondness of discussion, his willfulness, and his hot temper.”