Nature’s patterns

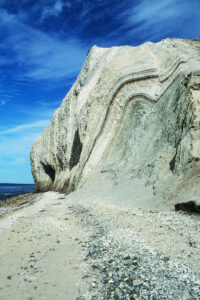

A beautiful pattern is created by these eroded rock formations, consisting of volcanic tuff, Göreme, central Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Light and shadows on a wall along a canal, overgrown by green algae, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers and leaves, which have been brought as an offering to the Hindu Water Temple near Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, are now floating on the surface of a pond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in a withered leaf, Basianshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“(…) in every case it was the northern face [of the dune], which was steep. On this side, the sand fell away from beneath the summit in an unbroken wall, set at as steep an angle as the grains of sand would lie. Down this face small avalanches constantly subsided, each fall leaving a temporary, light-coloured smear upon the surface of the sand. On either side of this face, sharp-crested ridges swept down in undulating curves, and behind them were other alternating ridges and troughs, smaller and more involved, as they became farther from the main face. The sand on the lower slopes at the back of the dune was firm, and rose and fell in broad sinuous trenches, or was dimpled with shallow holes. The surface of the sand was marked with diminutive ripples, of which the ridges were built from the heavier and darker grains, while the hollows were filled with the smaller paler-coloured stuff. Continuously, the wind shifted the sand, separating the heavier from the lighter grains, which are always of different colour. Only once did I notice sands, where the large were paler than the small. Although they are the least numerous, it is the large grains which give the prevailing hue to the landscape. Disturb the surface of the sand, and the underlying paleness is immediately revealed. It is this blending of two colours, which gives such depth and richness of the Sands: gold with silver, orange with cream, brick-red with white, burnt-brown with pink, yellow with grey – they have an infinite variety of shades and colours.”

British explorer and author Wilfred Thesiger (1910-2003) in his book Arabian Sands, Longmans 1959.

Ripples on a reddish sand dune, Sossusvlei, Namib Desert, western Namibia. These dunes and other natural phenomena in Namibia are described on the page Countries and places: Namibia – a desert country. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ripples on another sand dune in Namibia, near Swakopmund. Darker grains have gathered in the grooves. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ripples on a dune near Rabaa, Egypt. A species of tamarisk, Tamarix africana, is silhouetted against the dune. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in dunes, Maspalomas, Gran Canaria. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in a wandering dune, Råbjerg Mile, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) is a small gull, which is widely distributed in Arctic seas, breeding in colonies on steep rocks or cliffs, where each pair builds a nest, consisting of plants and seaweeds, on a narrow ledge. As a breeding bird, this species is found southwards to the Kuril Islands, southern Alaska, Newfoundland, the British Isles, and France, with scattered colonies in Portugal and Spain. In winter, it disperses to a huge area in subarctic and temperate seas.

The generic name is derived from the Icelandic name of the bird, rita, whereas the English name was given in allusion to its call. The specific name is from the Greek tridaktylos (‘three toes’), referring to the fact that this species is missing the small, back-pointing fourth toe, which most other gull species possess.

In North America, this species is called black-legged kittiwake to differentiate it from its near relative, the red-legged kittiwake (Rissa brevirostris), which breeds on small islands in the far northern Pacific.

White kittiwakes, breeding on a dark rock monolith, off Rauðanupur (‘Red Cliff’), northern Iceland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting kittiwakes, creating patterns in the Denmark Strait, between Greenland and Iceland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

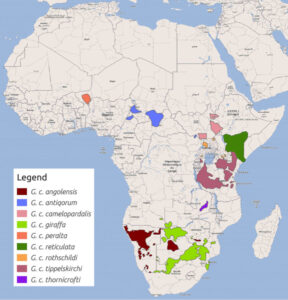

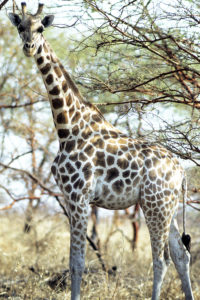

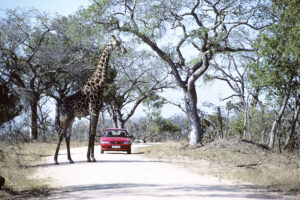

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) is one of only two living genera of the family Giraffidae, the other being the okapi (Okapia johnstoni) in Zaire.

The tall and seemingly ungainly giraffe was once distributed throughout Africa, except in rainforest. However, it has diminished alarmingly, and today there may be less than 100,000 individuals.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only one species of giraffe exists, divided into nine subspecies, whereas other authorities recognize up to eight separate species.

The generic name was derived from the Arabic zarafah, ultimately from Persian sotorgavpalang (‘camel-ox-leopard’), whereas the specific name is derived from the Greek kamelos (‘camel’) and pardos (‘leopard’), and the Latin alis (‘resembling’), alluding to its camel-like shape and leopard-like pattern.

This map shows the distribution of the nine subspecies of the giraffe. (Borrowed from Wikipedia)

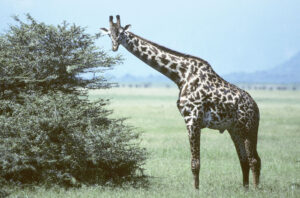

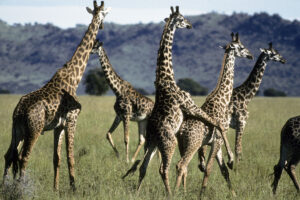

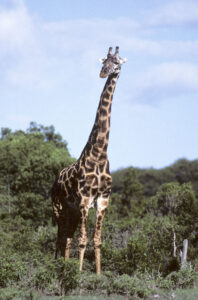

The Masai giraffe, subspecies tippelskirchi, lives in Kenya and Tanzania. It has a jagged pattern.

Masai giraffe, feeding on acacia leaves, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two bulls of Masai giraffe, engaged in dominance display. In turn they bang their head against the other bull’s neck. Afterwards, the dominant bull mounts its opponent. – Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The reticulated giraffe, subspecies reticulata, is native to southern Ethiopia, Somalia, and north-eastern Kenya. It has a reddish-brown rhombic pattern with narrow white stripes.

In Arusha National Park, northern Tanzania, the pattern of the local giraffes is quite unique, a mixture of reticulated and Masai giraffes. Some authorities regard them as hybrids between these two subspecies, naming them Galana giraffes.

Bulls of reticulated giraffe, engaged in dominance display, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reticulated giraffe, feeding on acacia leaves, Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A so-called Galana giraffe, maybe a hybrid between reticulated giraffe and Masai giraffe, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Kordofan giraffe, subspecies antiquorum, is distributed in southern Chad, the Central African Republic, northern Cameroun, and north-eastern Zaire. Formerly, it was believed that populations in Cameroun belonged to subspecies peralta, but genetic research has shown that this is incorrect. The pattern somewhat resembles that of the reticulated giraffe, but is much paler.

This subspecies is highly endangered, as only about 400 individuals survive in fragmented populations.

Kordofan giraffe, Waza National Park, Cameroun. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

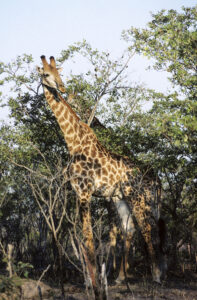

The southern giraffe, subspecies giraffa, lives in Botswana, northern South Africa, and south-western Mozambique. Its pattern is somewhat rhombic, pale brown with a darker centre.

The giraffe is a tall animal. Bulls can reach a height of almost 6 m, cows 5 m. – Southern giraffe, Krüger National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding southern giraffe, Krüger National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

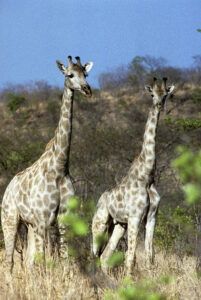

The Angolan giraffe, subspecies angolensis, is found in south-western Zambia, central Botswana, Zimbabwe, and northern Namibia. The pattern resembles that of the southern giraffe, but is usually much paler.

Angolan giraffes, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Angolan giraffes, Chief’s Island, Okawango, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Angolan giraffe, drinking from a waterhole, Etosha National Park, Namibia. The bird is a blacksmith lapwing (Vanellus armatus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Strangler figs are a group of fig trees that often begin their life as an epiphyte in another tree, where the seed often sprouts in a pile of bird dung, delivered by the bird that ate the fig fruit. Over the years, aerial roots of the strangler fig wrap around the host tree, growing down to the ground, where they take root. Eventually, the host tree is strangled to death, and as its trunk decays, it leaves the strangler fig standing as a hollow cylinder of aerial roots.

Other fig trees are presented on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

As the trunk of the host tree decays, it leaves the strangler fig tree as a hollow cylinder of aerial roots, here in the town of Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One strangler fig is pipal (Ficus religiosa), also called sacred fig tree, as it is sacred to Buddhists. It is described in depth on the page Plants: Pipal and banyan – two sacred fig trees. Most pipals begin their life as epiphytes, but also often grows in cracks on buildings. If left alone, its aerial roots will envelop the building and, over time, destroy it.

Morning light is reddening this row of pipal trees in the city of Taichung, Taiwan. This species is widely planted on the island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pipal may be identified by the broad, heart-shaped leaves, ending in a long, tapering point. This fallen leaf has been attacked by fungi. – Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The large-leaved fig tree (Ficus superba) is another strangler fig, which is distributed in China, Japan, and parts of Southeast Asia, southwards to Indonesia. Like pipal, it readily grows on buildings, and it is also able to thrive as a normal free-standing tree.

Aerial roots of a giant large-leaved fig, climbing over the remains of a former warehouse of Tait & Co., in the town of Anping, Taiwan. Today, the building is called Anping Tree House. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leaves of floating sweetgrass (Glyceria fluitans), eastern Jutland, Denmark. This species is described on the page Plants: Grasses. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cycads are ancient gymnosperms, which flourished during the late Triassic and the Jurassic, app. 225-150 million years ago. They have a woody trunk with a crown of large, stiff, evergreen, palm-like leaves, and plants are either male or female, both having a cone-like flowering club at the end of the trunk. Most species grow very slowly, and some specimens may be as much as a thousand years old.

Cycas rumphii is a small tree, growing to about 10 m tall, with a trunk to 40 cm across. The bright green leaves, to 2.5 m long, is divided into 150-200 leaflets. The species is native to Indonesia, New Guinea and Christmas Island, but is widely cultivated elsewhere.

The specific name was given in honour of Dutch naturalist Georg Eberhard Rumphius (1628-1702), who served as a military officer with the Dutch East India Company.

Cone of Cycas rumphii with seeds, Mayabunder, Andaman Islands, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A cultivated cycad, Encephalartos friederici-guilielmi, Botanical Garden, Cape Town, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stone with patterns, Lyø, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A jumble of of rosebay willowherb (Chamaenerion angustifolium) create a complicated pattern, Öland, Sweden. The upper ones are still unripe, whereas the lower ones have already spread their seeds. This species is described in depth on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Expanding wilderness. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green algae, growing on hairy bracket (Trametes hirsuta), a member of the polypore family (Polyporaceae), Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A close relative is Trametes versicolor, here photographed in Velling Skov, Jutland, Denmark. One of its common names is turkey-tail, given due to its shape and multiple colors, which resemble those of the tail of the wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yet another member of Polyporaceae, growing on a rotten stick in Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Knot in the trunk of a Norway maple (Acer platanoides), Funen, Denmark. This species is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spruces (Picea), a genus with about 35 species of conifers, are native to temperate areas of the northern hemisphere. Some species grow to a very large size, up to 60 m tall.

Resin, creating patterns on a spruce trunk, Gludsted Plantation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red campion (Silene dioica) in front of stacked spruce trunks, Plan de Gralba, Val Gardena, Dolomites, Italy. The red campion is described on the page In praise of the colour red. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-spotted longhorn beetle (Rhagium mordax) on a sawn spruce log, Jutland, Denmark. This beetle of the family Cerambycidae grows to about 2.3 cm long. It is found in the entire Europe, eastwards to Kazakhstan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Norway spruce (Picea abies) is native from Scandinavia and the Alps, southwards to the Balkans and eastwards to somewhere in Russia. Its eastern limit is very difficult to define, as it hybridizes freely with the Siberian spruce (P. obovata), which is distributed from western Russia and eastern Finland eastwards across Siberia. Norway spruce is widely planted elsewhere for its wood. The specific name abies is the Latin generic name of firs. This name was given in allusion to the fact that Norway spruce, at some distance, often resembles the common fir (Abies alba).

Stacked trunks of Norway spruce, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stacked trunks of Norway spruce, Store Hjøllund Plantation, Jutland, Denmark. A polyporous fungus, Ischnoderma benzoinum, is seen above. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in a sawn trunk of Norway spruce, Store Hjøllund Plantation. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis) is a huge conifer, which may sometimes grow to almost 100 m tall, with a trunk diameter over 5 m. It is by far the largest species of spruce and among the 5 largest conifers in the world, and the third-tallest.

It is a native along the American Pacific coast, from southern Alaska southwards to northern California. However, it is widely cultivated elsewhere in cooler regions around the globe.

The specific and common names refer to the community of Sitka in south-eastern Alaska, where it is common.

Patterns on a fallen trunk of Sitka spruce, Vrads Sande, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Schrenk’s spruce (Picea schrenkiana) can grow to a large tree, to 50 m tall and with a trunk diameter up to 2 m. It is restricted to the Tien Shan Mountains in Xinjiang, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, usually forming pure forests at altitudes between 1,200 and 3,500 m. Two subspecies are found, schrenkiana in Kazakhstan and Xinjiang, and tianshanica in Kyrgyzstan.

It was named in honour of Baltic-German naturalist Alexander von Schrenk (1816-1876), known for his expeditions to Central Asia and northern Russia, and author of Reise nach dem Nordosten des europäischen Rußlands, durch die Tundren der Samojeden, zum arktischen Uralgebirge (1848).

Early morning light on tall and slender Schrenk’s spruces, Arashan Valley, Kyrgyzstan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in a cut red cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata f. rubra), Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A fungus, Monilia fructigena, creates patterns on a rotten apple, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vegetation, creating patterns in an old lava flow from the Batur Volcano, Kintamani, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Firs (Abies), a genus with about 50 species of conifers, are mainly found in montane areas across Eurasia, North Africa, and much of North and Central America.

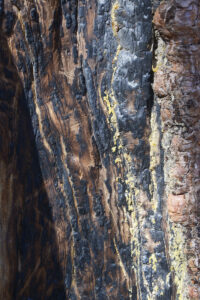

The Himalayan silver fir (Abies spectabilis) can grow to very large proportions, to 50 m tall, with a trunk up to 1.5 m across. This species is very common in the Himalaya, found from Afghanistan eastwards to Myanmar. It is widely used locally, its wood for construction, carpentry, furniture, paper-making, and firewood. The foliage is utilized medicinally for asthma, bronchitis, colds, and rheumatism, and is also burned as incense.

Patterns on the trunk of a burned Himalayan silver fir, encountered on the Lamjura La Pass (3530 m), Solu, eastern Nepal. The yellow fungus in the lower left part of the picture is a species of stagshorn (Calocera). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ponds, alternating with vegetation, creates a pattern, Izvilistaya River, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arisaema is a large genus in the arum family (Araceae), comprising about 200 species, distributed in southern and eastern Asia, southwards to Indonesia, and also in eastern Africa, southern Arabia, eastern North America, and Mexico. The largest concentration of species is in eastern Asia.

The inflorescence is very distinctive, with a large, often brightly coloured blade, the spathe, which encircles a central club-shaped axis, the spadix, on which numerous tiny flowers are clustered, male flowers above, females below. The tip of the spadix often has a flowerless part, the appendage. In many species, the flowers are foul-smelling, attracting flies that pollinate the flowers. The fruit is a club-like cluster of red berries, remaining on the spadix when the spathe has withered.

A common name of these plants is Jack-in-the-pulpit. It seems that to some people the flower resembles a person in a pulpit: ‘Jack’ is the flowering club, and the ‘pulpit’ is the spathe. Another name is cobra plant, referring to the cobra-like spathe on some species. The Nepalese name of the genus is sarpa ko makai (‘snake maize’), likewise alluding to the cobra-like spathe, and to the cluster of fruits, which resembles a maize cob.

The generic name is derived from the Greek arisamos (‘conspicuous’, ‘distinguished’), naturally alluding to the spectacular appearance of these plants. In some species, spathe and spadix have a thread-like tip, which is sometimes up to 1 m long.

Strikingly patterned spathe and spadix of Arisaema triphyllum, Meadow Brook Conservation Area, Haverhill, Massachusetts. This species is common in eastern North America, found from Manitoba eastwards to Nova Scotia, southwards to Texas and Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The fly amanita (Amanita muscaria) is described in depth on the page In praise of the colour red.

Cap of a fly amanita with white warts, remnants of the universal veil, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica) is an extremely poisonous viper, which lives in forests and savannas of sub-Saharan Africa. It has the longest fangs of any venomous snake, up to 5 cm long. Some authorities regard the western populations as a distinct species, named B. rhinoceros.

The specific and common names refer to Gabon, an area in Equatorial West Africa, named Gabão by the Portuguese, which was originally much larger than the present-day country of Gabon.

The diamond pattern down the back of the Gaboon viper is very beautiful. This one is lying on a sandy road in the Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The origin of the narrow-leaved primrose-willowherb (Ludwigia hyssopifolia), of the evening-primrose family (Onagraceae), is not clear. Today, this plant, which grows to 2 m, sometimes 3 m tall, is a very widespread weed of rice fields and wetlands in tropical and subtropical areas around the world. The upper stem is ribbed, and the leaves are lanceolate, to 10 cm long and 1-2 cm wide, with a short stalk.

The specific name refers to the likeness of its leaves to those of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis), of the mint family (Lamiaceae).

In the picture below, it is growing up a wall along a drainage canal in the city of Taichung, Taiwan. The wind has created a pattern by moving the plants back and forth, hereby scraping dust and dirt off the wall. The plant with white flowers is downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa), presented on the page Nature: Invasive species.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In one of his Just So Stories, English author Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) describes how the zebra got its stripes by standing half in the shade and half out, “with the slippery-slidy shadows of the trees” falling on its body.

But what is the true reason for these stripes, when, in other members of the genus Equus (horses and asses), the striping is limited to the lower legs, or entirely lacking?

Recent research has suggested that the stripes are a defence mechanism against blood-sucking flies, such as horseflies and tsetseflies, which transmit diseases like sleeping sickness, African horse sickness, and the potentially fatal equine influenza.

The thin coat of zebras does not give much protection against biting flies. However, analyses of the diet of tsetseflies have shown no trace of zebra blood. Research has shown that flies tend to avoid striped surfaces. Horseflies would hover in equal numbers around zebras and horses in the same enclosure, where some of the latter had been covered by black-and-white striped blankets. Far fewer flies would land on zebras or horses with striped blankets than on the horses without blankets. They would try to land on the stripes, but would then bounce off. (Source: bbc.com)

Three species of zebra live in Africa. The commonest and most widespread is the plains zebra (Equus quagga, previously known as E. burchellii). It was formerly far more widespread, but today the range is fragmented, with scattered populations of 5-6 subspecies found from southern Ethiopia southwards through eastern Africa to northern Namibia and north-eastern South Africa.

Plains zebras, subspecies boehmi, standing in front of basalt columns, Hell’s Gate, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plains zebras, subspecies chapmani, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. This subspecies may, or may not, have faint ‘shadow’ stripes in the white stripes. The bird in the lower picture is a yellow-billed oxpecker (Buphagus africanus), described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Previously, plains zebras in Namibia were regarded as a distinct subspecies, antiquorum. However, recent studies have revealed that it is genetically identical to Burchell’s zebra, subspecies burchelli, which was once regarded as extinct. As subspecies burchelli was described prior to antiquorum, the former name takes precedence. Thus, the plains zebras of Namibia are now called E. quagga ssp. burchelli.

Following the extermination of the quagga, ssp. quagga, in the late 1800s, Burchell’s zebra is today the least striped surviving subspecies. It is also characterized by having many faint ‘shadow’ stripes in the white stripes.

Burchell’s zebras, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi), which is slightly larger than the plains zebra, has a very limited distribution, found only in scattered grasslands in northern Kenya and eastern Ethiopia. It is a highly endangered species, whose population since the 1970s has dropped from c. 15,000 to only about 3,000. However, this number now seems to be fairly stable.

This zebra was described in 1882 by French naturalist Jean-Frédéric Émile Oustalet (1844-1905), who named it after Jules Grévy (1807-1891), president of France, who received a Grevy’s zebra as a gift by the government of Ethiopia.

Grevy’s zebra is beautifully patterned, as is evident from these pictures from Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. In the upper picture, beisa oryx (Oryx beisa) is also seen. This large antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Grevy’s zebra in Buffalo Springs National Park shows the distinct rump pattern of this species. The tail is squirting water drops up to the right. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The third species is the mountain zebra (Equus zebra), which is divided into two subspecies, the Cape mountain zebra, subspecies zebra, which is restricted to a few scattered herds in southern South Africa, and Hartmann’s mountain zebra, subspecies hartmannae, which lives several places in western Namibia and extreme south-western Angola. They differ from the plains zebra in being slightly smaller and by having stripes all the way down the legs.

By the 1930s, the Cape mountain zebra had been hunted to near extinction, and only about 100 individuals survived. Since then, strict conservation measures have had the effect that the population has increased to more than 2,700.

In 1998, the population of Hartmann’s mountain zebra was estimated at about 25,000 individuals, whereas recent estimates say around 33,000.

Cape mountain zebras, De Hoop Nature Reserve, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hartmann’s mountain zebra, Daan Viljoen National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common ragwort (Senecio jacobaea, also known as tansy ragwort, and in Latin Jacobaea vulgaris), is very common in open places, distributed in the entire Europe and northern Asia, southwards to northern Africa, Turkey, Tibet, and northern China. It has also become widely naturalized in many other places.

Leaf rosette of common ragwort, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The tufted duck (Aythya fuligula) is a small diving duck, widely distributed as a breeding bird in northern Eurasia. The northernmost populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as tropical Africa, India, and the Philippines.

Swimming tufted ducks create patterns in a moat, surrounding Nyborg Castle, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

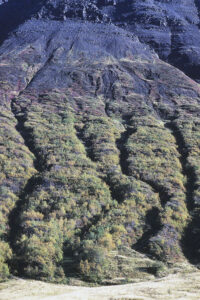

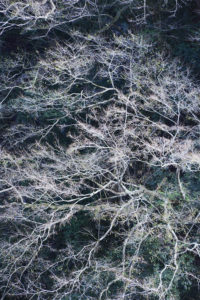

Planted trees create an intricate pattern, Huoyan Mountains (’99 Peaks’), Pinglin, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The striated swallow (Cecropis striolata, previously known as Hirundo striolata) is distributed from north-eastern India, south-western China, and Taiwan southwards through Southeast Asia and the Philippines to the major part of Indonesia.

Formerly, this bird was regarded as a subspecies of the widespread red-rumped swallow (C. daurica). The nominate subspecies is extremely similar to race japonica of the red-rumped swallow, which breeds in eastern China, Korea, and Japan. Striated tends to be a little larger and with less rufous on crown and cheeks, but the two species are very difficult to separate in the field. To me, it is a bit of a mystery why they are not regarded as a single species.

Other pictures, depicting striated swallows, may be seen on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

These striated swallows form ‘nodes’ on electrical wires, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These flat coastal rocks at Laomei, near Cape Fugueijiao, northern Taiwan, have been eroded into wedge-shaped, more or less parallel rocks, covered in a species of sea lettuce, Ulva compressa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In recent years, most populations of vultures, living in the Indian Subcontinent, have diminished alarmingly due to poisoning from diclofenac, a veterinary drug widely used to treat diseases in livestock. Research has shown that when these vultures feed on cattle carcasses, diclofenac will destroy their livers. The Himalayan griffon vulture (Gyps himalayensis), however, is still fairly common, as it lives in the high Himalaya, where cattle cannot thrive.

Symmetry. – Two slender-billed vultures (Gyps tenuirostris) dry their wings by spreading them out, facing the sun, near Pokhara, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

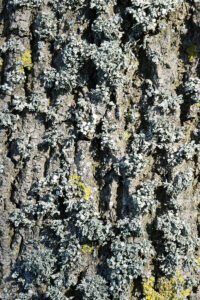

Lichens often form intricate and beautiful patterns on trees, rocks, and house walls.

The orange-yellow common orange lichen (Xanthoria parietina), also called yellow scale or shore lichen, is widespread and common, distributed in most of Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and North America. This species is one of the few lichens, which is favoured by eutrophication.

Other pictures, depicting orange lichens, are presented on the page In praise of the colour orange.

Common orange lichen, creating concentric rings on a stone wall, Hammershus, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another species of orange lichen, Xanthoria aureola, grows on coastal rocks. The picture below shows cracked rocks on the coast near Simrishamn, Skåne, Sweden. The green plants are thrift (Armeria maritima), which is described on the page Plants: Urban plant life.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lichens, growing on rocks of volcanic origin, Tongariro National Park, New Zealand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lichens, forming patterns on an overturned stelae from the Khmer culture, Ta Prohm, Angkor Wat, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Climbers, algae, and lichens create complicated patterns on the wall of an abandoned building, near Puli, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ring-shaped lichens on a tree trunk, Sun-Moon Lake, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grey lichens create patterns on the trunk of this European beech (Fagus sylvatica), growing at a lakeside in central Jutland, Denmark. This tree is described elsewhere on this page. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lichens, forming concentric rings on a rock, near Lake Tunnhovd, Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Furrowed bark and pale green lichens create a pattern on the trunk of this European larch (Larix decidua), Valsaparence, Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the trunk of this old European ash (Fraxinus excelsior), encountered on Funen, Denmark, lichens create a pattern on the bark, which in itself forms a pattern. Ash is presented in depth elsewhere on this page. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

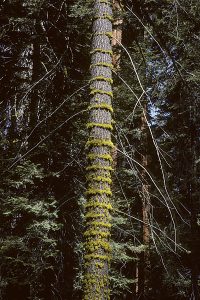

Wolf lichens (Letharia), of the family Parmeliaceae, are widely distributed in North America, Siberia, and Europe. In the old days, the common wolf lichen (L. vulpina) was utilized by the Norwegians to kill wolves and foxes. Its toxic foliage was mixed with crushed glass, and then stuffed into a carcass on frozen ground. (The specific name refers to foxes, in Latin Vulpes.)

This species, and the brown-eyed wolf lichen (L. columbiana), are both found in California, where many native peoples formerly utilized them for a variety of purposes. Their foliage was used to produce arrow poison. Klamath people would soak porcupine quills in an extract of the plants, which dyed them yellow. They were then woven into baskets to make patterns. The Okanagan-Colville tribe used these lichens medicinally, internally for stomach problems, externally for wounds.

This picture shows an unidentified species of wolf lichen, growing in concentric rings around the trunk of a white fir (Abies concolor), Sequoia National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), of the colubrid family (Colubridae), is widely distributed in North America, divided into c. 13 subspecies. The generic name is from the Greek thamnos (‘bush’) and ophis (‘snake’), whereas the specific name is from the Latin siratalis (‘resembling a garter’), in allusion to the stripes along its body.

The eastern garter snake, subspecies sirtalis, is found from southern Ontario and Quebec southwards to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the east coast to the Mississippi River.

Eastern garter snake, creeping by a fallen leaf of red maple (Acer rubrum), Caleb Smith State Park, Long Island. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Downy birch (Betula pubescens) and silver birch (B. pendula) are both widespread and common in Europe, in the Caucasus, and eastwards across Siberia to the Pacific, and silver birch is also found in China and Japan. The name birch is derived from Proto-Germanic berko, in all probability rooted in Sanskrit bhurja, the name of a species of birch.

These species are presented in depth on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Misty birch forest, near Moscow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In tidal areas, ripples are created by continuous beating of waves.

Ripples in a tidal area, Mols, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ripples in a tidal area, Ras Murundo, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ripples in a tidal area, Fanø, Denmark. The shells are of an American razor clam (Ensis americanus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ripples in a tidal area, Muriwai Beach, New Zealand. The birds are variable oystercatchers (Haematopus unicolor). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Petrified tidal ripples in Nexø sandstone, Gadeby, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

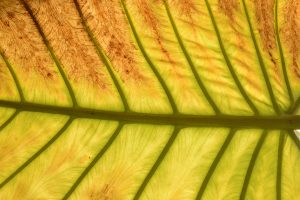

Leaf nerves often create very beautiful patterns.

The native area of the beach almond (Terminalia catappa), also known as country almond, Indian almond, Talisay tree, or umbrella tree, is unknown. Today, this species is widely distributed in most tropical and some subtropical areas of the world, growing in a wide range of habitats. Three of its popular names stem from the similarity of its fruits to those of the true almond (Prunus amygdalus), but the two species are not at all related, the true almond belonging to the rose family (Rosaceae), whereas beach almond belongs to the family Combretaceae.

Other pictures, depicting beach almond, are presented elsewhere on this page, and on the page Autumn.

Bright red winter leaf of beach almond, Taiwan. On this island, this species is widely planted as an ornamental tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cecropia is a genus, comprising about 63 species of trees of the nettle family (Urticaceae), ranging in height from 5 to 40 m. They are easily identified by their large circular leaves, to 40 cm in diameter, and deeply divided into 7-11 lobes. They are native from Mexico southwards to Tropical America, the majority growing in disturbed areas, including forest edges, roadsides, and landslides. For centuries, several species have been utilized medicinally for treatment of asthma.

The generic name refers to the Greek King Cecrops, who, according to legend, was the first king of Athens.

Cecropia angustifolia, previously known as C. polyphlebia, occurs in cloud forests from Puebla in Mexico southwards to Venezuela and Bolivia.

Leaf of Cecropia angustifolia, Monteverde Cloud Forest, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common oak (Quercus robur) is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Fallen leaf of common oak with dew drops, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

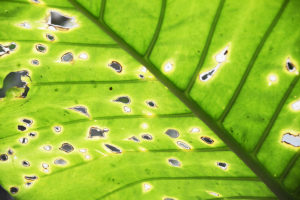

The giant taro, or giant elephant’s ear (Alocasia macrorrhizos), which grows to a height of 5 m, is native from Malaysia south through Indonesia to northern Australia, but has been introduced to many other tropical and subtropical areas as an ornamental, food crop, or animal feed. It is listed as an invasive species in Cuba, New Zealand, and several Pacific islands.

The gigantic leaves of this plant are often used as umbrellas. Its rhizome is edible when cooked for a long time, but the sap irritates the skin in your mouth, as it contains needle-like calcium oxalate crystals. In Hawaii, this plant is called ʻape, and they have a saying, Ai no i kaʻape he maneʻo no ka nuku. (’The one who eats ʻape, will have an itchy mouth’), meaning ’There will be consequences for partaking of something bad.’ (Sources: S. Scott & T. Craig, 2009. Poisonous Plants of Paradise: First Aid and Medical Treatment of Injuries from Hawaii’s Plants. University of Hawaii Press; and M.K. Pukui, 1986. ‘Ōlelo No’eau, Hawaiian Proverbs and Sayings. Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu)

Underside of a leaf of giant taro, Taiwan. On this island, this species is ubiquitous in the lowland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the leaf nerves, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the leaf nerves, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Design on a withering leaf of a close relative, Alocasia odora, Jiali Shan, Lion’s Head National Scenic Area, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wet rainforest leaf, seen from below, Sepilok, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The parasol-leaf tree (Macaranga tanarius), also called heart leaf or nasturtium tree, belongs to the spurge family (Euphorbiaceae). It is native to eastern China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, the Philippines, New Guinea, and eastern Australia.

The nerves on these leaves of the parasol-leaf tree create beautiful patterns against the light. These pictures are from Taiwan, where this species is very common. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dipterocarpus alatus is a large evergreen forest tree, which can grow to a height of 40 m, sometimes up to 55 m. It is found in tropical Asia, from Bangladesh eastwards through Southeast Asia to the Philippines. It is one of the most important timber species in this region, and wild populations are highly threatened by habitat loss. It is listed as Endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The generic name is derived from the Greek words di (‘two’), pteron (‘wing’), and karpos (‘fruit’). The fruits of this genus have two large wings, an adaptation to wind dispersal. A picture, depicting a fruit, is shown on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

These leaves of Dipterocarpus alatus have fallen among ruins in Angkor Thom, Cambodia. Micro-organisms have eaten most of the leaf in the lower picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turkish warty-cabbage (Bunias orientalis) is a member of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae), named after its warty siliques (fruits). This species is probably native to the Caucasus, central and southern Russia, western Siberia, and south-eastern Europe, north to Slovakia and Hungary. Today, however, it is very widespread in Asia, Europe, and North America, in some places regarded as an invasive.

On the island of Bornholm, Denmark, Turkish warty-cabbage is a common escape, here photographed north of the town of Gudhjem. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The genus Coccoloba, comprising between 120 and 150 species of shrubs, trees, and lianas, belong to the knotweed family (Polygonaceae). Members occur from Florida southwards through the Caribbean to tropical areas of Central and South America.

C. uvifera is native to coastal areas of Tropical America, the Caribbean, Florida, the Bahamas, and Bermuda. A popular name of this plant is seagrape, alluding to its grape-like clusters of green fruits, each to 2 cm across.

Underside of a leaf of Coccoloba uvifera with numerous galls, Tortuguero, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Multi-coloured leaf of a member of the arum family (Araceae), Parque Nacional de Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The rice-paper plant (Tetrapanax papyrifer), of the ivy family (Araliaceae), is endemic to Taiwan, but is widely cultivated in East Asia for production of the so-called rice paper, for usage in traditional Chinese medicine, and as an ornamental. It is a large shrub, growing to 7 m tall, its large leaves measuring up to 50 cm across.

Rice-paper plant, seen from below, Wushe, central Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rice-paper plant, seen from below, Wushe, central Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The broad-ribbed limpet (Patelloida saccharina) is a species of sea snail of the family Lottiidae. In China, it is known as chicken-footed limpet, due to the characteristic pattern on the shell. It is attached to exposed coastal rocks, found from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to the western Pacific, from Japan southwards via Melanesia to southern Queensland.

Broad-ribbed limpet, attached to a coastal rock at Jialeshuei, Kenting National Park, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gullies, eroded by rainwater, often form beautiful patterns.

Eroded gullies, Death Valley, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the years, these gullies at the foot of the mountain Fornastaðafjall, near Akureyri, Iceland, have been clad in forest of arctic downy birch (Betula pubescens var. pumila). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mustang is a very dry area in central Nepal, which, however, receives enough precipitation to create gullies, such as these, encountered in a bluff along the Jhong Khola River. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded gullies east of Fès, Morocco. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erosion from rainwater has cut deep gullies into this slope near Çankiri, north of Ankara, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eroded mountain slope and grazing horses, near the reservoir Embalse El Yeso (2560 m), Andes, central Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near Hinju, Markha Valley, Ladakh, northern India, snow-melt has created this rhombic-shaped gully. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gullies in eroded mountains, Sarchu, Ladakh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gullies in eroded sedimentary rocks, Badlands National Park, South Dakota, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These patterns on a sandy beach at Vangså, Thy, Denmark, have been created by waves, parting larger, darker sand grains from smaller, lighter ones. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young fern leaves, which are still not unfolded, are often very beautiful. Their rolled-up shape has been likened to the scroll, or head, of a fiddle, or violin, hence the popular name fiddleheads. Below, a selection of pictures show such ‘fiddleheads’ from around the world.

The common male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas) is widely distributed in temperate areas in the Northern Hemisphere.

As far back as the time of Greek scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371 – c. 287 B.C.), and physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica (five volumes dealing with herbal medicine), it was known that the rhizome of this species would expel intestinal worms.

English Medieval herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) writes: “The roots of the male fern, being taken in the weight of half an ounce, driveth forth long flat worms, as Dioscorides writeth, being drunke in mede or honied water, and more effectually if it be given with two scruples, or two third parts of a dram of scammonie, or of black hellebore: they that will use it, must first eat garlicke.”

Nowadays, herbalists do not recommend the rhizome of common male fern, as it is very poisonous.

‘Fiddleheads’ of common male fern, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The habitat of the cinnamon fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum) is moist woodlands and swamps. This spectacular fern is widely distributed, found in the eastern half of North America, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America, southwards to Paraguay. It also occurs in eastern Asia, from south-eastern Siberia southwards through Japan, Korea, eastern China, and Taiwan to the northern part of Indochina.

‘Fiddleheads’ of cinnamon fern, Shu Swamp, Long Island, United States. In the background leaves of eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cleared areas in the Himalaya, which lie fallow, are often invaded by large growths of a huge species of fern, Diplopterygium giganteum (formerly Gleichenia gigantea), which belongs to the family Gleicheniaceae, a group often called forked ferns. This species is distributed from Nepal eastwards to China and Southeast Asia.

‘Fiddleheads’ of Diplopterygium giganteum, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dicranopteris taiwanensis is a species of forked fern, which grows in forests of Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka.

‘Fiddleheads’ of Dicranopteris taiwanensis, Lugu, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Fiddleheads’, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Fiddleheads’, Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

‘Fiddleheads’, Dasyueshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grown ferns may also often create beautiful patterns.

Leaves of a tree fern, seen from below, Bedugul Botanical Garden, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The underside of leaves of western sword fern (Polystichum munitum) with sporangies, North Umpqua River, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon (top), and Fern Canyon, Van Damme State Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fern leaf, Dasyueshan National Forest, central Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common male fern (Dryopteris filix-mas), central Jutland, Denmark. This species is described above. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fern leaf, Santa Elena Cloud Forest, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The underside of a fern leaf with sporangia, Malabang National Forest, Hsinshu, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Winter leaves of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), Caldera Marteles, Gran Canaria. This species is described on the page Nature: Invasive species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These moss cushions form a distinctive pattern around leaf scars on the trunk of a tree fern, Trounson Kauri Park, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An epiphytic fern, growing on a slender tree trunk in a rainforest, is illuminated by a patch of sunshine, Sepilok, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Most members of the hard-fern genus, Blechnum, have rather short and rather stiff leaflets, but, as its name implies, the leaves of the palm-leaf fern (Blechnum novae-zelandiae) are larger, up to 2 m long and 50 cm wide, somewhat resembling palm leaves. This species, which is very common in New Zealand, may also be identified by its sporangies, forming at the tip of the leaves, which turn black when ripe.

Detail of a leaf of palm-leaf fern, Rotokura Lake, New Zealand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young leaflet of a fern, unfolding, Parque Nacional Volcán Poás, Cordillera Central, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shadows of serrated leaflets on this fern create zigzag patterns on other leaflets, El Yunque, Puerto Rico. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This climber grows out of a hole in the wall along a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. The wind has been moving the plant back and forth, hereby scraping dirt off the wall in concentric circles. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snow-bordered trail, leading up through a lava field on the slopes of Etna, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), also known by about a hundred other names, including lion’s tooth, cankerwort, milk-witch, Irish daisy, monks-head, priest’s-crown, blowball, puff-ball, face-clock, pee-a-bed, wet-a-bed, and swine’s snout, is native to the Northern Hemisphere, but has been introduced to most other parts of the world, where it has often become naturalized.

This species is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Leaf rosette of a dandelion, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On sandy beaches in tropical and subtropical areas you often come across patterns, consisting of tiny sand balls, which have been brought up and deposited by small crabs after each tide, which flushes sand into their dens. The pictures below show such patterns.

Cibu Wetlands, southern Taiwan. Patterns of ribs, created by waves, and washed-up foam, are also seen. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sipitang, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near Tongxiao, western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the islet Pulau Gaya, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum) is a stout umbellifer of the Mediterranean region, growing to about 1.8 m tall. In former days, it was much utilized as a pot herb, but has now largely gone out of use. The leaves are large, with rounded leaflets and a large, fleshy, boat-shaped leaf-stalk, yellowish with purple stripes.

The generic name is derived from the Greek smyrna (‘myrrh’) and ion, a diminutive suffix, stemming from the scent of the plant’s juice. The specific name is derived from the classical Roman name of the plant, olus ater (‘black herb’), referring to the colour of the seeds. The English name is a corruption of the Roman name, dating back to the Middle Ages.

The fleshy, purple-striped leaf-stalk of alexanders, Parco delle Madonie, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The hollow bolete (Suillus cavipes) may be identified by its hollow lower stem, and also by the pattern created by the pores, not unlike the spokes on a bicycle wheel. It is widely distributed, found in temperate areas of Eurasia and North America.

The generic name is derived from the Latin sus (‘pig’), thus ‘pig-like’, according to some sources alluding to the greasy caps of most species of the genus. I find this allusion strange, as pigs are not greasy, unless they have been rolling in mud. The specific name is from the Latin cavus (‘hollow’, ‘hole’), originally from Proto-Indo-European kowos (‘hollow’).

Pores on a hollow bolete, Nørlund Plantation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Norse religion, yellow bedstraw (Galium verum) was dedicated to Frigg, goddess of knowledge, love, and marriage, who was also protector of women giving birth. It was a custom to line the childbed with this fragrant herb. When Christianity was introduced, this heathen habit was banned, but as it persisted, the Church decided to dedicate yellow bedstraw to Virgin Mary instead, claiming that this herb was lining the crib of the newborn Jesus, hence the folk name of the species, Our Lady’s bedstraw.

Yellow bedstraw is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

At the edge of a gravel road in Småland, Sweden, the wind has been moving this yellow bedstraw back and forth, hereby creating a pattern of concentric circles in the sand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rainforest tree with buttresses, Corcovado National Park, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. This interesting area is presented on the page Travel episodes – Costa Rica 2012: Coastal hike to Corcovado. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The aardwolf (Proteles cristata) is a small relative of the hyaenas. It is fairly common in eastern and southern Africa, but is rarely seen due to its nocturnal habits. The name aardwolf is Afrikaans (the language spoken by immigrating Dutch Boers to South Africa), meaning ‘earth wolf’, relating to the fact that it lives in underground burrows.

Back pattern of an aardwolf, killed by a car, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

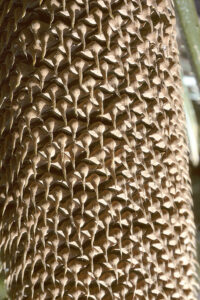

As trees age, beautiful patterns are often created by the texture of the bark. Lichens, growing on the bark, also often create decorative patterns.

Bark of an unidentified tree with lichens, Sanyi, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The flamboyant tree (Delonix regia), also called flame tree, is a huge tree of the pea family (Fabaceae), named for its gorgeous flowers. It is native to Madagascar, but is cultivated as an ornamental in almost all warmer countries.

A picture, depicting its huge, flat pods, which can grow to 60 cm long and 5 cm wide, may be seen on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Bark pattern of a flamboyant tree. This species is widely planted in Taiwan, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crepe-myrtles (Lagerstroemia), comprising about 50 species of trees and shrubs, are native from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to China, Taiwan, and Japan, and thence southwards through Indochina, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea to northern Australia, and some islands in the Pacific Ocean. Due to their beautiful flowers, many species are cultivated in numerous warmer areas.

The generic name was applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in honour of a Swedish merchant, Magnus von Lagerström (1696-1759), who was director of the Swedish East India Company. Lagerström was a keen naturalist, and despite never visiting Asia, he was able to procure many specimens from India and China, which he presented to Linnaeus. (Source: E. Bretschneider 1898. History of European Botanical Discoveries in China)

The Chinese crepe-myrtle (Lagerstroemia subcostata) is a smallish tree, to 14 m tall, with a characteristic smooth, pale or multi-coloured bark. It is native to Japan, Taiwan, China, and the Philippines, growing in forests and along streams, from low to medium elevations.

Multi-coloured bark on a Chinese crepe-myrtle, Sheding Nature Park, Kenting National Park, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

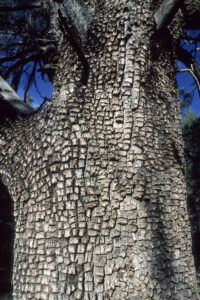

Alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana), also known as checkerbark juniper, has very distinctive bark, which cracks into small, square plates, thus resembling alligator skin. It is native from Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas southwards through Mexico to Oaxaca, growing at altitudes between 750 and 2,700 m.

The distinctive bark of alligator juniper, Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona.

The sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) is a native of Central Europe. It was introduced to Britain around 1500, and has also become naturalized in other parts of Europe, and in Australia, New Zealand, and North America. In many places, it has become invasive, easily spreading by its winged seeds, which are produced in the tens of thousands on a single large tree. An example of this invasiveness is described on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Expanding wilderness.

Bark on an old sycamore maple, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Peeling bark creates patterns on a sycamore maple, Hareskoven, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Concentric circles in the bark of a sycamore maple, presumably formed around a knot, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paperbark maple (Acer griseum), also known as blood-bark marple, is a small tree, to 9 m tall, characterized by its flaking, often reddish bark. It is native to montane areas of central China, growing at altitudes between 1,500 and 2,000 m.

Bark of paperbark maple, Edinburgh Botanical Garden, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pattern on a tree trunk, Shyabru, Langtang National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canary Islands pine (Pinus canariensis) is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Canary Islands pine, Plateau Presa de las Niñas, Gran Canaria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

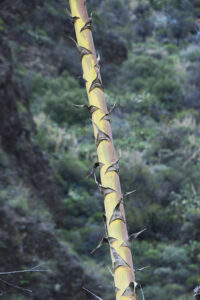

Aloidendron is a genus with 7 species of succulent shrubs and trees in the asphodel family (Asphodelaceae), distributed in arid areas of southern Africa, Somalia, and the Arabian Peninsula. These plants were formerly included in the huge genus Aloe, but, following genetic studies, they were moved to a separate genus in 2013.

The quiver tree (Aloidendron dichotomum, previously Aloe dichotoma), which grows to 6 m tall, is native to southern Namibia and the northern part of the Cape region of South Africa. It is also known as kokerboom, Afrikaans for ’quiver tree’. Boers who settled in the area noticed that the San people used the bark of this tree to make quivers for their hunting arrows.

Bark of the quiver tree is unique. – Keetmanshoop, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) is described in depth on the pages Natur: Invasive species, and Plants: Urban plant life.

Pattern in the bark of a young paper mulberry, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The rainbow eucalyptus (Eucalyptus deglupta) is characterized by its multi-coloured bark. It is the only species of eucalyptus growing in rainforests, native to the Philippines, Indonesia, and New Guinea, but widely cultivated elsewhere in tropical areas. It is one of the 4 eucalyptus species, out of more than 700, that do not occur in Australia.

Peeling bark of rainbow eucalyptus, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common, or European, ash (Fraxinus excelsior), of the olive family (Oleaceae), is a native of Europe, eastwards to the Caucasus and the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran. It has also become naturalized a few places in New Zealand, the United States, and Canada.

In later years, populations of ash have been much reduced by ash dieback, a disease caused by a fungus, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, previously called Chalara fraxinea. Most trees that contract this disease die after a few years. However, research has shown that some trees have resistance to it.

Patterns in the bark of an old ash, nature reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. A twig of cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera) is seen to the right. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The bark on this old ash has fallen off, revealing tunnels in the wood, made by the ash bark-beetle (Hylesinus fraxini). From the female’s egg-laying tunnel, the feeding tunnels of the larvae spread out like a fan. – Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The native area of the wild cherry (Prunus avium) was probably from France across central Europe to the Caucasus. At an early stage, however, it was cultivated throughout northern Europe, at least since the Viking Age, and today it is widely naturalized.

This species is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Narrow cork stripes create patterns on the bark of a wild cherry, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horizontal cork stripes as well as vertical cracks are present on yhis old wild cherry, eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen petals of wild cherry, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera), also known as myrobalan plum, is a close relative of the cherry. This small tree, sometimes reaching a height of 12 m, is a native of south-eastern Europe and western Asia. Due to its edible fruits, which taste somewhat like plums, it was introduced to most parts of Europe and North America at an early stage, and has become widely naturalized there.

The fruits occur in a wide variety of colours: yellow, pink, and numerous shades of red and purple, often produced abundantly. If they are not picked by people, they remain on the tree, until they are over-ripe and fall to the ground. Wild birds are not at all able to eat all these berries, which often lie almost in layers on the ground beneath the tree. Rotting cherry plums are much praised by butterflies and wasps. Pictures, depicting the fruits, are shown on the page Autumn.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kerasos (‘cherry’), and the Latin ferus (‘wild’).

Patterns on the trunk of an ancient, gnarled cherry plum, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in the stump of a logged cherry plum, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Despite its name, the Taiwanese cherry (Prunus campanulata) is also found in Japan, southern and eastern China, and Vietnam. It is a small tree, growing to 8 m tall. Due to its gorgeous bell-shaped flowers, this species is widely cultivated. When flowering, its nectar is a very popular food source for many bird species. On the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, numerous pictures depict birds feeding in these flowers.

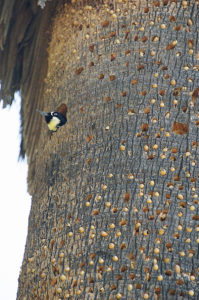

Patterns in the bark of a young Taiwanese cherry, Basianshan National Forest, Taiwan. The pink colour in the background stems from flowers of this species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The paperbark corkwood tree (Commiphora marlothii) is a small tree, to 9 m tall, native to rocky areas of central southern Africa, from southern Zaire southwards through Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana to northern South Africa. It is characterized by the bark, which peels off in yellowish, paper-like strips, exposing a green layer beneath. In the past, the bark of this tree was used by natives as writing paper.

The bark of the paperbark corkwood tree is highly distinctive, here photographed in Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Persian lilac, or Chinaberry (Melia azedarach), is probably native to Iran and the Indian Subcontinent. However, due to its beautiful flowers and fruits, it is widely planted elsewhere. It readily becomes naturalized and is now regarded as an invasive in several regions, including North America, East Africa, some Pacific Islands, New Zealand, and Australia.

The bark of old Persian lilac trees often forms cross-like patterns, like on this one in Taitung Ecological Park, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As silver birches (Betula pendula) age, the colour of the bark on the lower part of the trunk changes from almost pure white to blackish. This species is described in depth on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Patterns in the bark of a younger (top) and an older silver birch, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The cross-striped bark on this over-turned trunk of a silver birch contrasts greatly with the luminous moss, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The kauri tree (Agathis australis), or, to be more precise, the southern kauri tree, is a conifer of the family Araucariaceae, which is restricted to the northernmost part of New Zealand’s North Island. This species is among the world’s largest trees, growing to over 50 m tall, with trunk girths up to 16 m. Although their age is difficult to estimate, it is believed that they may live for more than 2,000 years. They are out of an ancient group of trees, which first appeared during the Jurassic period (190 to 135 million years ago).

The sad fate of the kauri is described on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Bark of a kauri, Trounson Kauri Park, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), also called tulip tree, whitewood, or fiddle-tree, belongs to the magnolia family (Magnoliaceae). It is one of the largest eastern American trees, sometimes reaching a height of 58 m, with a trunk diameter up to 3 m. It is distributed from southern Ontario and Vermont southwards to northern Florida, westwards to Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana. This popular tree is the state tree of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

The generic name, derived from Ancient Greek leirion (‘lily’) and dendron (‘tree’), the specific name, derived from tulip and the Latin fer (‘bearing’), as well as the common name tulip tree, all refer to the large flowers, which superficially resemble lilies or tulips. The popular name fiddle-tree refers to the peculiar shape of the leaves, which sometimes resemble small violins.

The characteristic furrowed bark of yellow-poplar often creates beautiful patterns. – Caumsett State Park, Long Island, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shadows from leaves of an American beech (Fagus grandifolia) are cast on the trunk of a yellow-poplar, Long Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Japanese zelkova (Zelkova serrata), of the elm family (Ulmaceae), is distributed in Japan, Korea, eastern China, and Taiwan. Leaves of the variety tarokoensis in Taiwan are smaller than in the nominate subspecies, and the teeth along the margin are also smaller.

Pattern in the bark of a Taiwan zelkova, var. tarokoensis, Malabang National Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The European, or common, hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), of the birch family (Betulaceae), is native to Europe and south-western Asia, from southern Scandinavia southwards to Italy and Greece, and from southern England and France eastwards to Ukraine, Turkey, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains of northern Iran.

A twig of an ivy (Hedera helix) clings to the trunk of a common hornbeam, Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pattern on the underside of fallen bark, Haverhill, Massachusetts, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colourful bug, Reserva Nacional Hacienda Baru, Costa Rica. Other true bugs are presented on the page In praise of the colour red. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rushing water from sudden outbursts of rainfall has created a complicated pattern in the river bed of the Kali Gandaki River, near Larjung, Annapurna, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Diploderma is a large genus of lizards in the family Agamidae, comprising about 46 species, which were previously included in the genus Japalura. They are native from Indochina eastwards across China to Taiwan and Japan, with the greatest diversity in China.

These animals are often perched on trees, especially in patches of sunlight. They feed on arthropods and other small invertebrates.

Swinhoe’s japalure (Diploderma swinhonis), also known as Taiwan japalure, is native to Taiwan. It is quite common, living in forests, shrubberies, and city parks. It was named in honour of British biologist Robert Swinhoe (1836-1877) who, in 1860, became the first European consular representative to Taiwan. He discovered many new animal species, and 4 mammals and 15 birds are named after him.

Swinhoe’s japalure males have a conspicuous pattern on their dewlap. – Chingshuian Recreation Area, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The short-legged japalure (Diploderma brevipes) is another japalure endemic to Taiwan, living in forests at elevations between 1,100 and 2,200 m. It grows to 25 cm long, of which the tail constitures about 15 cm. Males are strikingly patterned, with a yellowish or green back with large, dark brown patches, whereas the female is mainly green.

Male short-legged japalure, Malabang National Forest, Hsinshu, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Popular names of the genus Heliconia include lobster-claw, toucan beak, wild plantain, and false bird-of-paradise. Formerly, this genus, comprising about 200 species, was included in the banana family (Musaceae), but is now forming a separate family, Heliconiaceae. These plants are found mainly in Central and South America, with a few species on some Pacific Islands and in Indonesia.

Inflorescence of Heliconia wagneriana, Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. The native range of this species is from Chiapas, Mexico, southwards to Ecuador. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Even though you can hardly call fields nature, a few weeds always take root, a mole and a mouse or two may also live here, and an occasional deer or hare may be roaming. Under all circumstances, even modern large-scale fields hold a peculiar beauty in their broad outline, or in the patterns created by the harvesting of the crops.

The northern part of the island Luzon, Philippines, is inhabited by tribal peoples of Malayan origin. At least 2,000 years ago, they constructed fantastic terraced fields, irrigated through an advanced system of canals. On these terraces, they grow their main staple, rice, supplied with sweet potatoes, taro, and various vegetables.

Terraced fields, Banawe, Luzon, Philippines. Bundles of rice seedlings are placed in the fields, ready to be planted. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paddy fields with newly planted rice plants, near Longluan Lake, southern Taiwan (upper two pictures), and near Taichung, Taiwan. The bird in the centre picture is a cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terraced fields, lying fallow, near Chowki, eastern Nepal (top), and near Pokhara, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terraced fields, some lying fallow, others with yellow-flowered leaf mustard (Brassica juncea), Pharping, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. This species is presented on the page In praise of the colour yellow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terraced fields, enclosed by stone walls, Dingboche, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terraced fields, some lying fallow, Ilam, eastern Nepal. One field has been inundated to plant rice, and others are covered in leaf mustard. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Terraced fields with newly planted rice, near Lake Begnas Tal, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Harvested fields, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Onion fields on the lower slopes of Gunung Bromo Volcano, Java, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rows of cultivated dog roses (Rosa canina) on a hill, Funen, Denmark. The picture was taken with a 600 mm tele lens, causing the hill to look steeper than it is. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Harvested paddy field, Taichung, Taiwan. Some of the plants have sprouted anew. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stubble of harvested maize create a pattern, which merges into a pattern of trunks in a spruce plantation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Newly sprouted winter crop, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paddy fields, viewed from the hill Phnom Krom, near Siem Reap, Cambodia. In the lower picture, impressions from ox-cart wheels create patterns. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Seemingly endless rows of cultivated currant bushes (Ribes nigrum), Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Irregular patterns in rows of densely cut tea bushes (Camellia sinensis), near Alishan, Taiwan. – The origin of tea brewing is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tractor tracks in a grass field, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Newly sprouted corn, north of Aarhus, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Field of cereals with tracks from spraying, Djursland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Early in the morning, a patch of sunshine illuminates people, harvesting rice on terraced fields in the Trisuli Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Farmers, picking weeds in a wheat field, Sissu, Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As far back as Ancient Egypt, papyrus (Cyperus papyrus), of the sedge family (Cyperaceae), has been utilized by humans for production of paper – one of the first types of paper to be made. The stems were tied together to make reed boats – a production which still takes place several places on the planet (see page Culture: Boats). Mats, baskets, hats, fish traps, trays, and rope are also produced from them, and parts of the plant are edible.

The natural habitats of papyrus are swamps and lake margins, from Egypt southwards through the entire eastern Africa to South Africa, in some areas in western Africa, on Madagascar, and in Jordan and Israel.

Papyrus, Bangweulu Swamps, northern Zambia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns on a nest of a species of giant hornet, Vespa, hanging down from a branch, Wufong, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beeches (Fagus), comprising 10 to 13 species of trees, are native to temperate and subtropical areas of Europe, Asia, and North America.

The European beech (Fagus sylvatica) is largely restricted to Europe, occurring from England and the Pyrenees eastwards to Poland and Ukraine, and from southern Sweden southwards to Italy and the Balkans, with a patchy occurrence in southern Norway, central Spain, and Turkey. In the Balkans, it hybridizes with the oriental beech (Fagus orientalis), which is found in Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran.

Other pictures, depicting European beech, may be seen on the pages Plants: Ancient and huge trees, and Autumn.

Trunks of young beech trees cast shadows, which form patterns on the forest floor, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beech logs, lined up along a forest road, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The colourful Luna moth (Actias luna), of the family Saturniidae, is found in North America, distributed from Saskatchewan eastwards to Nova Scotia, and in the eastern half of the United States, southwards to Florida. It has been observed a few times in western Europe.

The specific name was applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-78), referring to Luna, the Roman moon goddess.

Fern-like antennae of a luna moth, Pawtuckaway State Park, New Hampshire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in algae, growing in a polluted stream, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foam, creating patterns on the surface of polluted streams, near Trounson Kauri Park, New Zealand (top), and Suei Wei River, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flower-like pattern on the skeleton of a washed-up sea urchin, popularly known as a ‘sand dollar’ due to its coin-like shape. – Yeliou Geopark, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stevns Klint, eastern Zealand, Denmark, is a white limestone cliff, 17 km long and a maximum of 41 m high. This cliff is of great importance due to a 5 to 20 cm thick layer of so-called fiskeler (‘fish clay’), a 65 million-year-old layer on the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. This ash layer marks the time, when an enormous meteor impact in Mexico caused widespread disasters across the globe and probably was the cause of mass extinction, including the dinosaurs. The reason that this layer of fiskeler is proof of the meteor impact is that it has a high content of a rare metal, iridium, which occurs in meteors.

Stevns Klint with black layers of flint. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hvideklint, on the island of Møn, Denmark, is a cliff, consisting of white chalk, with deposits of brown soil above. Rain has caused mud to run down the white chalk, creating a streaked pattern. The deposit of rust to the right indicates the presence of iron ore in the cliff. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common whitetail (Plathemis lydia), also known as long-tailed skimmer, is a striking dragonfly of the family Libellulidae, which is widespread in North America. The male, to about 5 cm long, has a broad white abdomen and blackish-brown bands on the translucent wings. Females are a bit smaller, with a different wing pattern of brown spots, and a brown abdomen with white zigzag stripes on the sides. Immature males resemble females, but have the wing pattern of adult males.

Immature male common whitetail, Mystery Hill, New Hampshire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lesser bulrush (Typha angustifolia) is characterized by its very narrow leaves, to 1.5 cm wide. It is widely distributed in wetlands in temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

Moved by the wind, leaves of lesser bulrush create a pattern, Langeland, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The barn owl (Tyto alba) is distributed in Europe, from England and Denmark southwards, and from Ireland and Portugal eastwards to Belarus and Ukraine, in the entire Africa (except certain areas of the Sahara), on Madagascar, and on the Arabian Peninsula. Previously, it was believed that it had an almost global distribution, but the former Asian, Australian, and American subspecies have now been upgraded to a number of separate species.

Pattern on the upper wing of a barn owl, which was killed by a car, France. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The long-eared owl (Asio otus) is a widespread and common owl, breeding in subalpine, temperate and subtropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere, southwards to the Mexican border, northern Africa, Turkey, Afghanistan, northern China, and southern Japan. Northernmost populations are migratory, wintering as far south as central Mexico, Egypt, Pakistan, and southern China.

Primary flight-feathers of a long-eared owl, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patterns in a sawed trunk, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large honey bush (Melianthus major), of the family Francoaceae, is an evergreen shrub, which is endemic to South Africa, but has become naturalised elsewhere, including in India, Australia, and New Zealand. All parts of the plants are poisonous. The generic name is from the Greek meli (‘honey’) and anthos (‘flower’). Various birds, including sunbirds of the family Nectariniidae, often feed in the flowers.

Leaves of large honey bush are very distinctive. – Doubtless Bay, Karikari Peninsula, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reflections of sunlight create patterns in a rocky lake-bed, Lake Femunden, Hedmark, Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rushes (Juncus) are a huge genus of grass-like plants, comprising about 300 species. They are found throughout the world, with the exception of Antarctica. Historically, these plants received little attention from botanists. In 1819, British botanist James Ebenezer Bicheno (1785-1851), who was colonial secretary of Tasmania from 1842 until his death in 1851, described the genus as “obscure and uninviting”. (Source: J.E. Bicheno 1819. Observations on the Linnean genus Juncus, with the characters of those species, which have been found growing wild in Great Britain. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 12 (2): 291-337)

Saltmarsh rush (Juncus gerardii) is mainly a coastal species, occurring on coasts of Europe and eastern North America, and also on saline soils inland, in western and central Asia and central North America.

These tufts of saltmarsh rush, which have sprouted between large specimens of sea plantain (Plantago maritima), create patterns in a littoral meadow, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. A littoral pond with vegetation of common cordgrass (Spartina anglica) is seen in the background. The greyish plants are sea wormwood (Artemisia maritima). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)