Webs

Araneid spider in its web, covered in morning dew, woven between stems of rosebay willow-herb (Chamaenerion angustifolium), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Following a night with heavy dew, it is clearly revealed, how many webs of common hammock-weaver (Linyphia triangularis) are adorning this common box (Buxus sempervirens), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Silken nest of an unidentified moth, shimmering in the sunshine, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araneid cobwebs, suspended from a gutter, Funen, Denmark. The plant is a hollyhock (Alcea rosea). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a quiet October day, myriads of young spiders have landed in this meadow in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark, where their silk threads create a transparent carpet, as far as the eye can reach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spiders

Old fat spider, spinning in a tree!

Old fat spider can’t see me!

Attercop! Attercop!

Won’t you stop,

Stop your spinning and look for me?

Old Tomnoddy, all big body,

Old Tomnoddy, can’t spy me!

Attercop! Attercop!

Down you drop!

You’ll never catch me up your tree!

Lazy Lob and crazy Cob

are weaving webs to wind me.

I am far more sweet than other meat,

but still they cannot find me!

Here am I, naughty little fly;

you are fat and lazy.

You cannot trap me, though you try,

in your cobwebs crazy.

From the novel The Hobbit (1937), written by British philologist and author J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973). When the dwarves, who are the companions of the hobbit Bilbo Baggins, are caught by huge spiders, Bilbo uses his magic ring to become invisible, singing this song to lure the spiders away from the dwarves, who have been stunned and are now hanging in webs to ‘ripen’.

The word attercop is derived from Old English attor-coppa, the term for spider, taken from Old Norse edderkop (‘poison-head’), referring to spiders having a poisonous sting. Lob and Cob also mean ‘spider’. The term tomnoddy means ‘a foolish or stupid person’.

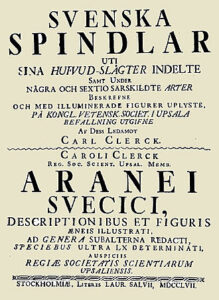

The book Svenska Spindlar, in Latin Aranei Svecici (‘Swedish spiders’), published 1757, was the first comprehensive book on the spiders of Sweden and one of the first regional monographs of a group of animals worldwide, written by Swedish arachnologist and entomologist Carl Alexander Clerck (1709-1765).

The full title of the book is quite laborious, in Swedish: Svenska Spindlar uti sina hufvud-slägter indelte samt under några och sextio särskildte arter beskrefne och med illuminerade figurer uplyste, på Kongl. Vetensk. Societ. i Upsala befallning utgifne.

In Latin: Aranei Svecici, descriptionibus et figuris æneis illustrati, ad genera subalterna redacti, speciebus ultra LX determinati, auspiciis Regiæ Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis.

Translated to English: “Swedish spiders into their main genera separated, and as sixty and a few particular species described and with illuminated figures illustrated, published by order of the Royal Scientific Society in Upsala.”

Title page of Carl Alexander Clerck’s book Svenska Spindlar. (Illustration: Public domain)

Dust-covered cobwebs in a stable window, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Raindrops create a beautiful pattern in a cobweb, Luzon, Philippines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers, fallen from a mu oil tree (Vernicia montana), have been caught in cobwebs, Sanyi, Taiwan. In the bottom picture, a puff of wind makes the flower sway. This tree is described on the page Plants: When the mu oil tree is flowering. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Numerous spider webs in a bush, shimmering in the sunshine, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rain drops in a cobweb, Mingtsih, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A tiny spider in its web, spun between two stems of common bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris), Basianshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rime, covering a single thread of a cobweb, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Small spider in its web, probably a species of Octonoba, family Uloboridae, Malabang National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cobweb with dew, Cascade Range, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Autumn is the time, when young spiders spread. They climb to the top of vegetation, where they spin a disperse-thread, waiting for a puff of wind to carry them out into the world. It often happens that thousands of young spider land on a field, where their silk threads form a transparent carpet.

Young spiders, huddled together in their web before they disperse, flying with the wind at the end of a silk thread, which they spin themselves. – Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a quiet October day, myriads of young spiders have landed in this meadow in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark, where their silk threads create a transparent carpet, as far as the eye can reach. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agelenidae Funnel weavers

A huge, almost worldwide family with about 92 genera and 1,400 species. These spiders build a dense web in grass or in holes, with a funnel-shaped retreat for the animal, where its sits, waiting for prey to pass by.

Web of an unidentified funnel weaver, Güzelyurt, east of Aksaray, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araneidae Araneid spiders

This cosmopolitan family, comprising more than 3,000 species, is well-known to most people, as many of these spiders are quite colourful, and their webs are often found in gardens and along roads. Initially, araneid spiders make a framework of non-sticky threads, before adding final spirals of threads, covered in sticky drops.

These spiders are also called orb-weavers, from the old English word orb, meaning ‘ball-shaped’ or ‘circular’, in this case referring to the circular webs, which are suspended among vegetation, in fences, and other places.

The European garden spider, or cross orb-weaver (Araneus diadematus), is widespread, found from the major part of Europe across the Middle East and Central Asia to the Far East, where it is native, and in North America, where it was initially introduced, but has spread across the continent.

It is very variable, the colour ranging from pale yellow to orange, brown, dark grey, or almost black, all with mottled white markings across the dorsal abdomen, often forming a cross.

Female garden spider in its web in a window sill, with egg cocoon and newly emerged young. Above are the remains of a spider, perhaps eaten by the garden spider. A couple of days after this picture was taken, the spider had made a new cocoon and laid eggs in it, and its abdomen was now much smaller. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The marbled orb-weaver (Araneus marmoreus) is sometimes called pumpkin spider due to the resemblance of the female’s abdomen to a pumpkin. It is distributed in temperate and subarctic areas, from Europe eastwards to Japan, and also in North America, where it occurs from Canada and Alaska southwards to Texas.

Marbled orb-weaver, cleaning its web of seeds of rosebay willow-herb (Chamaenerion angustifolium), Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araneid cobwebs in a tree, Malabang National Forest, Hsinshu, Taiwan. The reddish colour in the background are young leaves of a maple species (Acer). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araneid cobweb with dew drops, Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An araneid spider in its web, which is not quite completed, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Araneid cobweb, covered in dew drops, woven between wires in a fence, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Unfinished webs of araneid spiders, Taiwan (top), and Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning dew in a web of an araneid spider, Jughandle State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The wind has blown numerous seeds of rosebay willow-herb (Chamaenerion angustifolium) into this cobweb of an araneid spider, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Small araneid spider, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the town of Anping, southern Taiwan, aerial roots of a giant large-leaved fig (Ficus superba) have completely enveloped a former warehouse of the company Tait & Co. Today, the building is called Anping Tree House. Other pictures from this building are shown on the page Plants: Urban plant life, whereas large-leaved fig and other fig species are presented on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

Sunshine, reflecting all colours of the rainbow in the web of an araneid spider, Anping Tree House. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Argiope

Members of this genus of araneid spiders, comprising about 90 species, are distributed in all warmer areas of the world. Their web is quite large and often rather invisible, with the exception of a pure white silk pattern in the centre, made from densely woven threads, which form an X or a zig-zag pattern.

The spider sits with one pair of legs in each of the four directions of the X, or aligned with the zig-zag pattern. This often makes the animal extremely visible, and many scientists have speculated as to what purpose this pattern is made. One theory is that its visibility might prevent large animals from accidentally destroying the web. Research has also shown that the pattern reflects ultra-violet light, which may attract prey to the web.

Argiope lobata is widely distributed in Africa, southern Europe, and western Asia. This one was photographed in Zaire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Argiope in Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica, has caught a bush-cricket and is now entangling its prey in silk threads. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another Argiope from Cahuita. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Web of a small Argiope in a field of young rice plants, Bali, Indonesia. Its legs are aligned with the zig-zag pattern. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Argiope argentata is sitting in its web, its legs aligned with the X-shaped figure, Cahuita National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pattern of silk threads in the web of this Argiope argentata is indeed conspicuous, but the spider itself is well camouflaged. – Reserva Nacional Hacienda Baru, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nephila Golden orb-weavers

This is another striking genus of large araneid spiders, comprising about 10 species, distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, Australia, and islands in the Pacific.

The female, which is many times larger than the male, can grow to 6 cm in body length, with a leg span up to 15 cm, whereas the body length of males is only around 6 mm.

The generic name is derived from the Greek nein (‘to spin’) and philos (‘love’), thus ‘fond of spinning’. The web of these spiders is enormous, up to 2 m across, with supporting strands much longer. The webs of different females are sometimes inter-connected, together covering many square metres. Small birds and bats are reported to have been caught in these strong webs.

Nephila pilipes Asian golden orb-weaver

A widespread species, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, Taiwan, and Japan, and thence southwards to Australia.

Once, when I was hiking up the Marsyangdi Valley in central Nepal, I observed some children throwing something at female hikers, who then screamed and ran for dear life, while the children were laughing heartily. When I asked the children what they were doing to the poor tourists, they showed me several large orb-weavers, which they had collected from nearby webs.

Dorsal views of female Asian golden orb-weavers. They were encountered in Taiwan, where this species is very common in the lowlands and lower mountains. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ventral views of females, Taiwan. In the upper picture, a tiny male is seen to the left. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trichonephila Golden orb-weavers

Members of this genus, counting about 12 species, are also called golden orb-weavers, as they were previously included in the genus Nephila (above). They are distributed in most warm areas of the world.

Trichonephila clavata Joro golden orb-weaver

This spider is found in Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan. Since 2014, or probably earlier, it has also been present in the United States, presumably introduced by humans. As of 2022, it has been reported from Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Maryland, Oklahoma, and West Virginia.

The female has a very colourful abdomen, with yellow and reddish-brown patterns. In Japan, it is known as jorogumo, derived from joro (‘prostitute’) and gumo (‘spider’). In Japanese folklore, jorogumo is a legendary creature, known for its allure and deadly nature. It is often depicted as a spider, which is capable of transforming into a seductive woman to lure unsuspecting victims. (Source: jorospider.com/jorogumo-legend)

Joro golden orb-weaver females, Aowanda National Forest (top) and Basianshan National Forest, Taiwan. Remains of their prey are hanging in the webs. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female joro golden orb-weaver in its web, which is full of dew drops, Lugu, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trichonephila clavipes American golden orb-weaver

This species, sometimes called banana spider, inhabits forests and woods in a huge area, from the southern United States southwards to Argentina. In summer, it may stray as far north as south-eastern Canada, but at these latitudes it seldom survives the winter.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘club-footed’, presumably referring to the striking tufts of hair on the legs of the female.

Dorsal view of a female American golden orb-weaver, Reserva Nacional Hacienda Baru, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trichonephila comorana Comoro Islands golden-legged orb-weaver

As its name implies, this spider is endemic to the Comoro Islands. The body of the female is about 5 cm long, with a legspan up to 15 cm. Its body colour is mainly black, whereas the legs have a striking pattern of alternating orange-yellow and black. The male, whose body is only 5-6 mm long, is mainly reddish-brown.

Most authorities place this animal in the genus Nephila, which is most odd, as the very closely related African golden-legged orb-weaver, found in southern Africa, and on Madagascar, the Seychelles, Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues, is placed in the genus Trichonephila, named T. inaurata.

Indeed, I find it strange that the animals on the Comoro Islands should be a separate species, as those on all the surrounding islands are regarded as belonging to the African species. So maybe they are the same species?

Comoro Islands golden-legged orb-weaver females, Itsoundzou, Grand Comore. In the lower picture, 2 tiny males are also present. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Linyphiidae Hammock-weavers

These small spiders, also called sheet-weavers, live almost worldwide, counting more than 4,300 species. Their common names stem from their densely woven web, which resembles a hammock or a sheet. Another popular name of this group is money spiders, from an old European superstition, claiming that if a sheet-weaver spider would run over a person, it would spin new clothes for you – meaning good fortune, moneywise.

Morning dew in a hammock-weaver web, Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another hammock-weaver web with dew drops, Dasyueshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The common hammock-weaver (Linyphia triangularis) was first described by Swedish entomologist and arachnologist Carl Alexander Clerck (1709-1765) in his 1757 book Svenska Spindlar (see above).

This small spider, growing to 6 mm long, is abundant throughout Europe, and has also been introduced to north-eastern United States. It lives in low vegetation, where it spins a horizontal sheet-web, waiting on the underside for prey. Small insects, which climb on a maze of web threads above the horizontal sheet-web, may fall down onto the sheet, where they are killed by the spider.

Thousands of common hammock-weaver cobwebs in a field of rapeseed, covered in dew drops, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Numerous webs of common hammock-weaver among common hair-grass (Deschampsia flexuosa), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Following a night with heavy dew, it is clearly revealed, how many common hammock-weaver webs are adorning this common box (Buxus sempervirens), Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hammock-weaver cobwebs in a marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre), heavy with dew, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Webs of common hammock-weaver among grass and heather (Calluna vulgaris), Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pholcidae Cellar spiders, skull spiders

A large family with about 94 genera and more than 1,800 species, distributed on all continents, except Antarctica. They spin an irregular web in caves, or under rocks or loose bark, and in inhabited areas in houses, cellars, garages, and the like.

The name skull spider alludes to Pholcus phalangioides, whose front part of the body slightly resembles a human skull. The body of adult females is about 8 mm long, males a bit smaller, whereas the legs are 4 or 5 cm long. Originally, it was native to warmer parts of Asia, but has been spread by people to all continents, except Antarctica. It has spread considerably in northern Europe in later years. It is completely harmless to humans.

Pholcus phalangioides, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tetragnathidae Long-jawed spiders

A large family with about 50 genera and 1,000 species, found across the globe, except in the polar regions.

One member of the family is the European cave spider (Meta menardi), which is distributed from Scandinavia and Britain southwards to North Africa, and thence eastwards to Korea and Japan. Adults shun light, living in dark places, such as caves, tunnels, and mines, but will emerge around dusk to hunt, often using a single silk lasso line, which is thrown on their prey.

This picture is from Helligdomsklipperne, Bornholm, Denmark, where the European cave spider has survived in coastal caves for at least 12,000 years. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Moths

Caterpillars of an unidentified moth, huddled together in their communal web in a barberry bush (Berberis), whose leaves they have eaten, Langtang National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda), searching for caterpillars in a dense cluster of cobwebs, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. This colourful member of the crow family is native to the Indian Subcontinent, southern China, and Indochina. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Notodontidae

A huge family with several subfamilies, many genera, and about 3,800 species, distributed across the globe, with a core area in the New World tropics.

Thaumetopoeinae Processionary moths

These moths got their name from the behaviour of the caterpillars, which march in long columns through the forest, each larva with a firm grip on the rear end of the preceding one (except the leading animal, of course). These marching caterpillars are on their way to pupate in the ground. They are very conspicuous, and would seemingly be vulnerable to enemies. However, they are protected from predators by their severely irritating hairs, which sometimes cause allergies in people.

As its name implies, the pine processionary moth (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) lays eggs on pines, and the larvae, which live communally in large silken nests, are highly destructive to pine forests, often defoliating entire growths. Previously, this species was native to southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, but the global warming has had the effect that it is spreading northwards, and is now found as far north as northern France.

French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre (1823-1915) conducted a famous study on the pine processionary caterpillar, described in his book The Life of the Caterpillar (1916). In this experiment, a group of caterpillars marched head-to-tail in a circle around the rim of a flower pot, continuing for a week. He concluded that the caterpillars were mindless automatons, trapped because they were pre-programmed to blindly follow the preceding animal.

Silken nest of pine processionary moth in a pine, Etna, Sicily. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Abandoned nest of pine processionary moth in a pine, Karaburun Peninsula, near Izmir, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marching caterpillars of pine processionary moth, near Castelbuono, Sicily. This column contained almost 200 animals. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yponomeutidae Ermine moths

This family, divided into 5 or 6 subfamilies, contains several hundred species, most of which live in tropical areas.

Yponomeuta

This genus has more than a hundred species, some of which are agricultural pests.

The caterpillars are gregarious, spinning silk webs and feeding on the leaves within them. When the larvae pupate, they spin silk cocoons around themselves, hanging vertically inside the web. These caterpillars often occur in such numbers that the host tree or bush becomes completely defoliated. In such cases, the larvae spin silk threads to the ground, where they pupate under plants.

Yponomeuta cagnagella Spindle ermine moth

The native range of this species, in America known as euonymus webworm, is throughout Europe and the Middle East, eastwards to Siberia. It has also become naturalized in north-eastern North America. The adult moth has a wingspan, ranging from 19 to 26 mm. Its host plant is the European spindle tree (Euonymus europaeus).

Caterpillars of the spindle ermine moth are very characteristic, yellowish-white with black spots along the sides. These, encountered on the island of Bornholm, Denmark, have almost defoliated a spindle tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yponomeuta padella Orchard ermine moth

This moth, also known as the cherry ermine moth, has a wingspan slightly smaller than the previous species. The larvae feed on leaves of sloe (Prunus spinosa), wild cherry (P. avium), and various species of hawthorn (Crataegus). It is widespread, found from Europe eastwards to central Asia, southwards to the Caucasus and Kazakhstan. It has also been accidentally introduced to North America.

These sloe bushes have been defoliated by caterpillars of the orchard ermine moth, Karl X Gustaf’s Wall (top), and Hallnäs Udde, both Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded February 2018)

(Latest update August 2024)