Megaliths

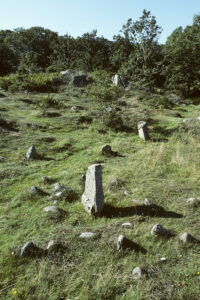

Kellerød Langdysse, a longbarrow in southern Zealand, Denmark, is among the largest megalithic structures in the country, c. 125 m long, with 150 stones along the edge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

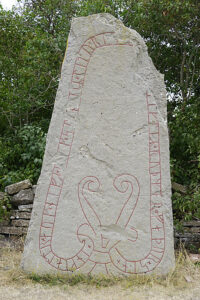

The text on this runic stone at Bjärby, Öland, Sweden, translates as follows: “Härfrid and Vidbjörn erected this stone to commemorate Fastulv, their father. Siglaug erected (it) to commemorate her husband. He is buried inside the church.” – To be buried inside the church was probably a great honour in the early days of Christianity. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Djoser’s Step Pyramid, Saqqara, Egypt, was built during the reign of Pharaoh Djoser (also called Zoser, or Netjerykhet), who ruled 2630-2611 B.C. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The word megalith is derived from the Greek mega (’large’) and lithos (’stone’). Usually this word indicates large, undressed stones in prehistoric structures. On this page, however, I take a somewhat broader perspective, including ancient monuments of dressed stones, such as runic stones, pyramids, and obelisks.

Without a doubt, the world’s most famous megaliths are Stonehenge, situated in Wiltshire, southern England. Many of us are familiar with the annual news clips, showing thousands of modern druids in white robes, communing at Stonehenge each summer solstice. They claim a common law right to celebrate here the rites that their priesthood practiced for many centuries.

This claim may well be true, but it is less well known that by the time the first Celtic druids arrived in England, Stonehenge had been in use for thousands of years and then had already been abandoned for centuries. The druids may have adopted it, but they had no more idea than we do today, who built it or why.

In reality, Stonehenge consists of two structures: a stone circle and a henge, the latter simply being a ring-shaped ditch. At Stonehenge, 80 magnetic bluestones, transported c. 225 km via sea and land, were placed in two concentric circles inside the ditch.

An even larger henge is Avebury Henge, likewise in Wiltshire. In this structure, an enormous number of stones were erected inside a huge henge, c. 2500 B.C. Two parallel stone rows, today called West Kennet Avenue, connects Avebury Henge with nearby Overton Hill. The stones in these rows act like bar magnets, with all their north poles lined up in the same direction. Perhaps this was done to direct ions to the great stone circle at Avebury.

Structures like Stonehenge, Avebury Henge, and West Kennet Avenue show links with electro-magnetic energies and increased crop production. This fascinating theory, proposed by my late friend John Burke, is discussed in detail on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

John Burke’s comprehensive work is described on the page People: John Andrew Burke (1951-2010).

Stonehenge. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stone row in the inner circle, Avebury Henge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The resting sheep give an impression of the size of this gigantic stone at Avebury. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These parallel stone rows, called West Kennet Avenue, connect Avebury Henge with nearby Overton Hill. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

King’s Men, or Rollright Stones, a Neolithic stone circle near Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, England. The stones are covered by lichens. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

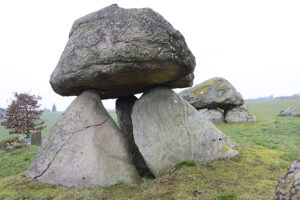

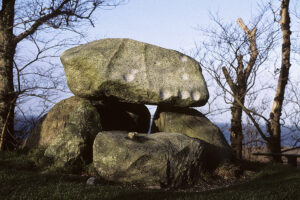

Dolmens and longbarrows, the latter also called passage graves, are megalithic structures, erected during the Stone Age, c. 3500-3000 B.C. Dolmens are the oldest type, typically consisting of 5 or 6 large stones, erected closely together and covered by a larger stone. Longbarrows are rectangular, consisting of many large standing stones, covered by several even larger stones. On one side, an entrance tunnel, made of stones, was constructed.

John Burke at Sømarkedyssen, dolmens on the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Altogether 7 dolmens have been preserved near the village of Lindeskov, eastern Funen, Denmark.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Poskær Stenhus (‘Poskær Stone House’), a dolmen on Mols, Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The small depressions on this dolmen on the island of Lyø, Denmark, called Klokkestenen (‘The Bell Stone’), appeared over time, when thousands of people hit the stone with a small rock, hereby producing a bell-like sound. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dolmens near Kirke Stillinge, western Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Poll na mBrón (Poulnabrone Dolmen), on The Burren, near Glencolumcille, Ireland, is a portal tomb from between 4200 and 2900 B.C. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Table des Marchand, a dolmen at Locmariaquer, Brittany, from about 3900 B.C., is of a type called a passage grave. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

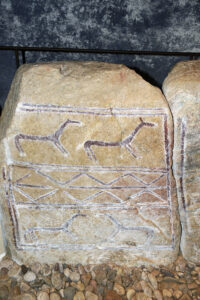

Some of the stones in Table des Marchand have been decorated with engravings, depicting axes and other items. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two of the enormous stones in West Kennet Longbarrow, from c. 3500 B.C., Wiltshire, England. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Balanced Rock is a pre-Columbian dolmen at North Salem, New York State, consisting of a 90-ton granite boulder, balancing atop several slabs of granular quartz. Geologists have labeled it an accidental glacial erratic, but it sits precisely over a major magnetic anomaly, and brilliant golf-ball sized lights have repeatedly been photographed circling it.

This structure shows links with electro-magnetic energies and increased crop production. It is described in depth on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

Balanced Rock, North Salem, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hesselbjerg Langdysse, a longbarrow on the island of Langeland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

View out from Kong Asgers Høj (’King Asger’s Mound), a longbarrow on the island of Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grønhøj (‘Green Hill’), a longbarrow near Horsens, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foggy day at a longbarrow, Jægerspris, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Entrance to a reconstructed passage grave, Dún Fhearghusa (also known as Newgrange), erected between c. 3300 and 2900 B.C., eastern Ireland. On the large stone are engravings, including spirals. Through the opening above the large stone, at Summer Solstice, sunlight penetrates into the inner chamber. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Er Grah is a barrow, or tumulus, 140 m long, situated on the Locmariaquer peninsula, Brittany. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grand Cairn de Barnenez, Brittany, a 75 m long and 28 m wide grave complex from the Late Stone Age. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A røse is a Bronze Age burial mound, constructed of stones, which form a flattened cone with a depression in the centre.

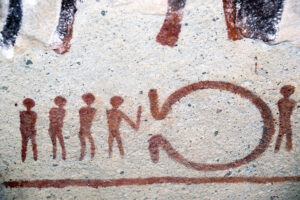

This huge røse, named Kivik Royal Tomb, is situated in eastern Skåne, Sweden. A burial chamber was found beneath the depression, containing stone slabs with numerous petroglyphs. – Other pictures, depicting Bronze Age petroglyphs, are shown on the page Culture: Folk art around the world. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large standing stones without inscriptions, with a French term named menhir, were erected numerous places in Europe during the Late Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age.

Around 4700 B.C., at present-day Carnac, Brittany, Stone Age farmers began erecting more than 10,000 menhirs in very long rows, running alongside and parallel to an unusual geophysical frontier, where seismic, gravitational, and magnetic gradients coincide. My late friend John Burke was convinced that these rows were erected to enhance yield of crops. (More about this theory on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty.)

Menhirs, Carnac. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This menhir in Brittany, called Kerampeulven, is 6 m tall. In the old days, women who wanted babies joined hands around the stone. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The 20 m long Le Grand Menhir Brisé, on the Locmariaquer peninsula, Brittany, weighed about 280 tons and would have required about 3,800 adults to be dragged and hoisted into place. Today, this gigantic menhir has fallen, broken into four pieces. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Menhir, Pointe de Primel, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This menhir, called the Giant of Manio, is situated near the Kerlescan alignment of standing stones at Carnac, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another menhir near the Kerlescan alignment, Carnac. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Menhirs are a very common sight in Sweden. These, named Kungsstenarne (‘King’s Stones’), were erected at a burial site from the Iron Age (c. 500 A.D.) at present-day Ottenby, Öland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Denmark, menhirs are most common on the island of Bornholm. This one was erected during the Bronze Age at Stammershalle, northern Bornholm. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

North of Gudhjem, Bornholm, these Iron Age menhirs, named Hestestenene (‘Horse Stones’), are situated near the coast. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Menhirs on The Burren, a rocky area near Glencolumcille, Ireland. Stone fences and grazing cattle are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Limestone menhirs, erected during the Iron Age, Karums Alvar, Öland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near the village of Listed, Bornholm, a group of Iron Age menhirs is called Sacred Woman and Her Ten Children. According to a local legend, the Sacred Woman turned her children into stones, to avoid them being killed – indeed a strange act, because aren’t stones also dead?

In former days, towards evening, it was a custom to respectfully greet these menhirs, otherwise you might have bad luck.

Sacred Woman and Her Ten Children, Bornholm. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Prehistoric menhir in a group of monoliths, called Nether Largie, near Kilmartin, Scotland. In the background grazing sheep. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grave from the Iron Age, Stammershalle, Bornholm, Denmark. The stones are placed around the central menhir to form a star. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At various locations in Scandinavia, megaliths dating from the Bronze and Iron Ages, were erected to form the outline of huge ships.

Ales Stenar, near the village of Kåseberga, Skåne, Sweden, is a megalithic structure from the Bronze Age, consisting of c. 60 stones, erected to form the outline of a ship, c. 80 m long and 20 m wide. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Gettlinge Gravfält, Öland, Sweden, stones have been placed to form the outline of a ship. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Hjortahammar Gravfält, near Almö, Blekinge, Sweden, stones have been placed to form the outline of a ship. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Noahs Ark, a 30-metre-long stone setting from the Iron Age, shaped like a ship, Karums Alvar, Öland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At some point during the Iron Age, it became a custom in Scandinavia to erect large stones of granite or slate, so-called runic stones, on graves, engraved with runes, most often in long bands, in many cases ending in a serpent’s or dragon’s head – most probably an image of the Midgard Serpent, a monster which was feared among seagoing peoples, as it supposedly ate drowned seamen.

In many places, erecting runic stones only became a practice, after people had converted to Christianity, around 900-1000. For this reason, inscriptions on these stones all have a Christian stamp. In most cases, they shortly inform you, for whom the stone was erected, and by whom.

Runic stones in front of ruins of the former Østermarie Church, Bornholm, Denmark. A cross is engraved into the left stone, while the other is adorned with runes, which translate as follows: “Bjarne and Tue and Asgot erected this stone to commemorate their brother Sibbe. Christ help his soul.” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the rear side of the low runic stone above, a large flower-like figure, a so-called propeller cross, is engraved. The stones in the background are menhirs, large stones without engravings. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Tullstorp Stone, a runic stone from about 980, Tullstorp Church, Skåne, Sweden. The images depict a mythical beast, which resembles a stylized lion, and a Viking ship. The text says: “Klibir auk Osa ristu kuml Þusi uftir Ulf” (“Klibir and Ose carved these runes after Ulf”). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Runic stone from around 1050, Gårdby Church, Öland, Sweden. The text says: “Härtrud placed this stone after her son Smed, a good man. His brother Halvboren sits in Gårdarike. Brand carved well, so that you can interpret.” – Gårdarike was the Nordic name of Swedish Viking possessions in Russia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marevadstenen is a runic stone from c. 1100, standing outside Hasle Church, Bornholm, Denmark. The runes on this stone, carved in the form of a serpent, translate as follows: “Aulakr erected this stone to commemorate his father Sasur, a good farmer. God and Saint Michael help his soul.” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On Karlevistenen, a runic stone on Öland, Sweden, Sibbe the Wise One wrote: “In this barrow lies hidden the one, who did the greatest deeds. Never again, shall a more righteous and strong shipmaster rule over Danish lands.” – In those days, Danish kings ruled in this part of Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cross, carved into a runic stone in front of Vestermarie Church, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Runes, engraved as a serpent-like figure on a stone slab, situated near Segerstad, Öland, Sweden. The text translates as follows: “Ingjald and Näv and Sven erected this stone to commemorate their father, Rodmar.” – Näv is a nickname, meaning ‘the one with the nose’ – the person in question probably had a big nose! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On this runic stone at Svaneke Church, Bornholm, Denmark, the text translates as follows: “Bove let this (stone) erect to commemorate his good father Økil. Christ help his soul.” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

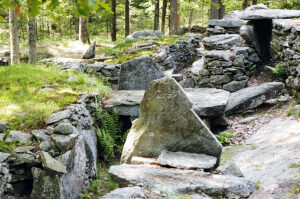

Near Kent Cliff, New York State, is a pre-Columbian megalithic structure, a rock chamber, which was erected atop a strong magnetic anomaly in the ground. The air inside the chamber has an unusual electric stratification, consisting of positively charged ions near the floor, while lighter, negatively charged ions rise to near the ceiling.

This structure shows links with electro-magnetic energies and increased crop production. It is described in depth on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

Pre-Columbian rock chamber at Kent Cliff. The plants with yellow flowers are greater celandine (Chelidonium majus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

America’s Stonehenge is a complex of Native American rock chambers and standing stones in New Hampshire, United States, whose purpose is still shrouded in mystery – hence the name of the place, Mystery Hill. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The so-called Sacificial Stone outside the Oracle Chamber, Mystery Hill. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

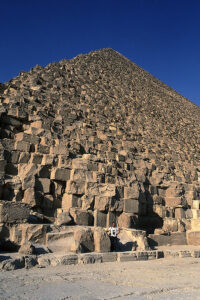

The Giza Pyramids in Egypt were built during the reigns of Pharaohs Khufu, called Cheops by the Greeks (ruled 2551-2528 B.C.), Khefren, also called Rakaef (ruled 2520-2494 B.C.), and Menkaure, called Mycerinus by the Greeks (ruled 2490-2472 B.C.).

For more than 3,000 years, the Khufu Pyramid was the largest man-made structure in the world, until the Great Wall of China was constructed. Its height is 137 m, its perimeter more than 1 km.

These huge structures are usually labeled as tombs, but a far more interesting theory can be read on the page Books: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

The Giza pyramids in late afternoon light, from left Menkaure, Khefren, and Khufu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the Khufu Pyramid. The person indicates the grand scale of this structure. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

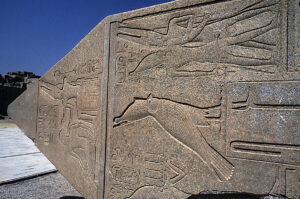

Obelisks are columns, erected during the reign of the Pharaohs of Egypt.

Engravings on the toppled obelisk of Queen Hatsepsut, at the Great Temple of Amun, Karnak, Luxor, include a picture of the god Horus, depicted as a falcon wearing a double crown, which was a symbol of the united Egyptian kingdoms. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the evening, the obelisks of the Luxor Temple are illuminated. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tikal is an area in northern Guatemala with numerous Mayan ruins. These fascinating structures are described in depth on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders. Our adventures in Guatemala are related on the page Travel episodes – Guatemala 1998: Land of the Mayans.

These huge structures are usually labeled as tombs, but a far more interesting theory can be read on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders.

These Mayan ruins at Tikal, Guatemala, are the so-called Great Jaguar’s Temple, popularly called ‘Queen’s Temple’ (left), and Temple II, or ‘King’s Temple’. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another Mayan ruin at Tikal is known as El Mundo Perdido (‘The Lost World’). This highly energetic, flat-topped pyramid was in continuous use for 1,300 years, from 600 B.C. to 700 A.D. It is situated on ground that contains extremely powerful electromagnetic energies, and the structure itself further concentrates these energies. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Construction of Great Zimbabwe, capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe, took place between the 11th and 15th Centuries A.D. It is believed that this stone city, which covers an area of 7.2 km2, was the residence of a local king. At its peak, it would have housed about 18,000 inhabitants.

Watchtower in the wall, surrounding the ‘Great Enclosure’, Great Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One of the ‘Hill Ruins’, Great Zimbabwe, in late afternoon light. The bird circling above the ruins is a white-necked raven (Corvus albicollis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

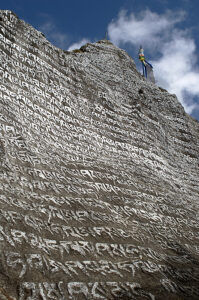

In Buddhist areas of the Himalaya, Tibetan mantras are chiseled on numerous stone slabs or rocks. It is believed that this act will benefit the carver in his next life. Such decorated rocks or stone slabs are called mani stones. The most commonly chiseled mantra is Om Mani Padme Hum, which loosely translates as Hail Jewel in the Lotus Flower – a symbol of the Buddha.

Mani stones and other aspects of Buddhism are described on the page Religion: Buddhism.

This rock near Namche Bazaar, Khumbu, eastern Nepal, is covered in chiseled Buddhist mantras. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stela with engravings, including a sun icon, near Séipéilín Ghallarais (Gallarus Oratory), a church from about the 8th Century, Dingle, Ireland. This church is shown on the page Religion: Christianity. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Christian stone cross from the 1200s, Kapelludden, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded September 2016)

(Latest update July 2024)