Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Jordan 1977: Late autumn in Jordan

In early November, we drive south through Germany and Austria to the Balkans, where we enjoy the warm climate for some days before continuing towards Turkey.

In northern Greece, we make a stop for the night at the large Lake Volvi, which is teeming with little cormorants (Microcarbo pygmaeus), coots (Fulica atra), and common pochards (Aythya ferina). We observe no less than 4 species of grebes, crested (Podiceps cristatus), black-necked (P. nigricollis), red-necked (P. grisegena), and little (Tachybaptus ruficollis). Other birds included glossy ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) and water rail (Rallus aquaticus).

“Go to Jordan! Go, go!” they say.

In the Jordanian customs, the staff ransack our car, whereupon they hand us a form. We are ushered into an office, where we are handed another form. In the passport control, the staff do not want these forms, but the ones which we filled in when entering Syria. However, we obtain visas for Jordan without any further problems. When we ask for the duration of the visa (which is not obvious from the stamp), one of the staff says: “One week, one month, two months.” – It seems that we can decide ourselves!

Now for the carnet. In yet another office, a staff member tears out the exit slip from Syria, and we are told to go to another office to get a form, which costs 1 Dinar. There is nobody in this office, in which a lot of planer shavings litter the floor. After a while a staff member enters, and we get our form. Then back to the former office, where a fellow fills out a couple of forms, demanding half a Dinar as ‘stamp fee’. (On the form is printed that the price is 375 Fils, so we suppose that he puts the rest in his pocket).

During our wanderings back and forth in the customs area, we note a small restaurant, which also has a sign saying “All traveller’s requirements.” We need to get a map of Jordan, and I enter to ask for one. One of the staff shows me a map measuring about 10 x 10 cm, with names in Arabic. I decline his offer.

When leaving the customs area, a soldier controls our passports, and without the slightest trace of irony, he says: “Welcome to Jordan!”

Arne and I look at each other, smiling. Our troubles here remind us of what we experienced in Baghdad 5 years previously, related on the page Travel episodes – Syria & Iraq 1972: “Welcome to Baghdad!”

We also encounter two species, which are endemic to the Levant and surrounding areas, white-spectacled bulbul (Pycnonotus xanthopygos) and Palestine sunbird (Cinnyris osea). The white-spectacled bulbul is distributed from southern Turkey southwards through Israel, Jordan, and western Saudi Arabia to Yemen and Oman. It was formerly regarded as a subspecies of the garden bulbul (P. barbatus), which is found in Africa, southwards to Gabon and Zaire. The Palestine sunbird is found from southern Lebanon and Syria southwards to the Sinai Peninsula, and along the west coast of Saudi Arabia to Yemen and Oman.

The Jordan River joins the Dead Sea, in Arabic al-Bahr al-Mayt, and in Hebrew Yam Hammelah – a large lake, which today covers about 605 km2. Its size is steadily shrinking; in 1930 it covered about 1,050 km2. The lake has no outlet, and its salinity is around 34%. This means that you float like kork on the surface. The environment is too harsh for plants and animals to flourish, hence the name of the lake.

We decide to check it out, but are sorely disappointed. The oasis is somewhat greener than the surrounding desert, with a few waterholes, but as many Arabs use it as a hunting area, the ‘sanctuary’ part of the brochure is a blatant lie. We do observe some birds, but the larger ones, such as ducks, are very shy due to the hunting. The commonest birds are redshank (Tringa totanus), water pipit (Anthus spinoletta), white wagtail (Motacilla alba), and starling (Sturnus vulgaris).

Exit Azraq!

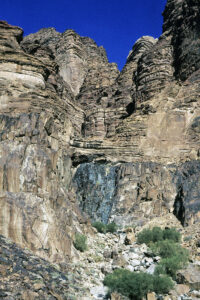

Arne and I are searching for a wadi, where we want to spend some time away from tourists, and locals who want you to rent a camel ride, or to buy souvenirs and other rubbish.

From a distance, Wadi Zarqa Ma’in looks promising, fresh and green. In this case, the word wadi is misleading, as the river bed almost always contains water due to a large number of cold and hot springs that emerge here.

To our horror, the road terminates at a site, where a spa is under construction around the mineral springs. We talk to some of the workers who inform us that a huge hotel and 200-300 bungalows are going to be built, and bath houses are going to be erected over some of the springs. Toilets, an electric plant, a police station, and a mosque have already been completed, but apart from the mosque they already show signs of decay; garbage and broken glass litter the ground, and for some reason or other fences of barbwire criss-cross the site.

Disappointed, we drive back up the road, but to our immense relief we find a tranquil and lush place near the stream, where we can park our car and spend some days. In fact, we grow quite fond of the place, and after paying a visit to the southern parts of Jordan, we return to it.

The wadi is home to a rich bird life, and we observe numerous species. The rock pigeon (Columba livia) is very common. This species was tamed at a very early stage and is the progenitor of the domestic pigeons, which are so common in cities around the globe. It is described in depth on the page Animals: Urban animal life.

Other common birds include white-spectacled bulbul, sand partridge (Ammoperdix heyi), rock martin (Ptyonoprogne fuligula), little swift (Apus affinis), Spanish sparrow (Passer hispaniolensis), and black redstart (two subspecies, one with black belly, one with red).

As it turns out, a dark bird, which flies around in flocks, is a kind of starling of the genus Onychognathus, with 11 species, 9 of which live in Africa. The one that we observe here is Tristram’s starling (O. tristramii), which is native to Jordan, Israel, the Sinai Peninsula, western Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Oman. The remaining species is restricted to the island Socotra, off Somalia and Yemen.

Tristram’s starling was named in honour of English clergyman and naturalist Henry Baker Tristram (1822-1906), who was secretary to the governor of Bermuda 1847-1849. He explored the Sahara, and in 1858, 1863, and 1872 he visited Palestine, to identify localities mentioned in the Bible, and to make observations of natural history. In 1881, he travelled to Palestine, Lebanon, Mesopotamia, and Armenia.

The blackstart (Oenanthe melanura) is a small grey bird with a black tail, which flits about, hunting insects. Genetic research has revealed that this bird, which was formerly placed in the genus Cercomela, is in fact a wheatear of the genus Oenanthe.

Two impressive Bonelli’s eagles (Aquila fasciata) are soaring above the tallest of the crags. Presumably they have their nest there.

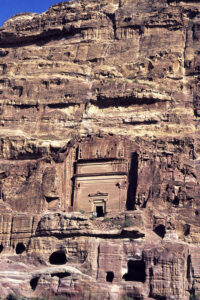

As sea trade routes emerged, the importance of Raqmu declined, and in 106 A.D. it was conquered by the Romans, who renamed the Nabataean kingdom Arabia Petraea (‘Rocky Arabia’). In the Byzantine era, several Christian churches were built in Petra, but the city continued to decline, and by the time the Muslims gained power in Jordan, the city had already been abandoned. Only a handful of nomads resided here.

The area remained unknown to the West, until it was rediscovered in 1812 by Swiss traveller and orientalist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817), who travelled in Arabia under the name Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah. He also travelled in Egypt, as far south as present-day northern Sudan, but was stopped by hostile tribals. On his way back, he was the first European to see the great temple at Abu Simbel, built during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II. He died of dysentery in Cairo, only 32 years old.

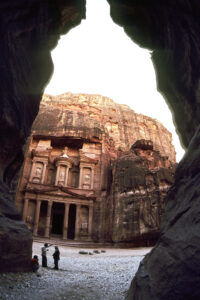

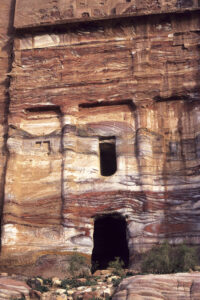

Access to the ruins at Petra is through a very narrow gorge, called the siq, which is just 3 metres wide at the narrowest point. At the end of the gorge, a marvellous scene is revealed towards al-Khazneh (‘The Treasury’), the most elaborate of the buildings in Petra, carved into a sheer sandstone rock wall, c. 130 m tall. It is thought to have been the tomb of a Nabatean king.

Several bird species are typical of this area, including the fan-tailed raven (Corvus rhipidurus), which may be identified by its very short tail. It is distributed from Syria and Jordan southwards through the entire Arabian Peninsula, and in north-eastern Africa, from the Nile valley southwards to South Sudan and Kenya, westwards to the Aïr Massif in Niger. It lives in deserts and other dry country, placing its nest in craggy areas.

The mourning wheatear (Oenanthe lugens) is a widespread bird, found in rocky areas of the Middle East, from eastern Egypt eastwards to Iran, and from southern Turkey southwards to Yemen and Oman, and also in northern Africa. It is quite common in Jordan.

The Sinai rosefinch (Carpodacus synoicus) is restricted to rocky country in eastern Egypt, southern Israel and Jordan, and north-western Saudi Arabia. The male is very colourful, whereas the female has a uniform brown plumage.

Other common species of the area include desert lark (Ammomanes deserti), white-spectacled bulbul, crested lark (Galerida cristata), house sparrow (Passer domesticus), goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis), and graceful warbler (Prinia gracilis), a very small bird with a long tail, which is often pointing upwards.

Both plants and animals are scarce here. We only observe 8 species of birds, and in low numbers: Raven (Corvus corax), long-legged buzzard (Buteo rufinus), desert lark, Tristram’s starling, Sinai rosefinch, white wagtail, mourning wheatear, and white-crowned wheatear (Oenanthe leucopyga). The latter is distributed in Jordan, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, and also in northern Africa, southwards to Mauritania and northern Ethiopia.

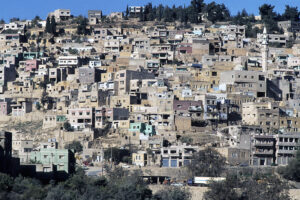

We drive to Aqaba to have a glimpse of the Red Sea, but are sorely disappointed: a small harbour, a cluster of dirty houses, a noble bank quarter, where also a few souvenir shops are situated, and a beach front with expensive hotels, surrounded by fences of barbwire to keep the mob away. A public beach with a few palm trees is a mess of garbage and broken glass, and the beach itself is stony.

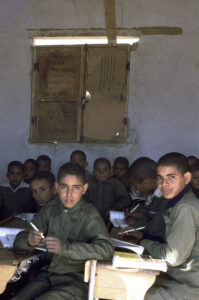

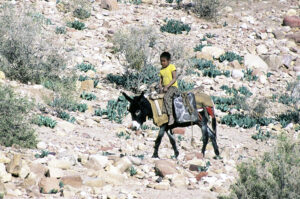

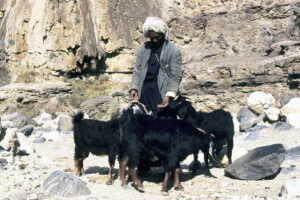

North of Aqaba we give a lift to 3 school teachers on their way to 3 small schools along the road, where they teach bedouin children. No public busses ply this route, so the have to get lifts every day, and the truck drivers often take money for a lift. They invite us in for a cup of tea. The rooms are very cold, and here 10-15 boys, aged 6-14 years, are sitting, shivering in their thin clothes. There are no girls. The teaching is very superficial, as one teacher has to teach all grades at the same time.

“Life is very difficult,” they say. They are paid 50 Dinars a month, of which 5 Dinars is spent for room rent in town, c. 5 Dinars to truck drivers, and an unspecified amount for food and other necessities.