Invasive species

White-tailed deer hind (Odocoileus virginianus), jumping over a fence, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The golden apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata) is considered to be among the world’s one hundred worst invasive species. This picture shows its pink egg masses, clinging to a dead shrublet, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa) with a feeding small cabbage white (Pieris rapae ssp. crucivora), Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) produces lovely fruits. – Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An invasive species is an animal, plant, or fungus, which is not native to a specific area, and which tends to spread beyond control, causing damage to the environment and often expelling native species. Most of these harmful species have been introduced by man, deliberately or accidentally.

The term invasive is sometimes applied to native species, whose numbers increase to an extent that they become harmful to their environment. Three such examples are white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in North America, and common broom (Cytisus scoparius) and bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) in Europe.

On this page, the species are divided into three categories: animals, plants, and fungi. Animals are divided into sections on mammals, birds, and invertebrates. Each section is arranged alphabetically according to the scientific family name, generic name, and specific name.

Animals

Mammals

Bovidae

Capra hircus Domestic goat

As a close acolyte of Man for thousands of years, the domestic goat is now found in almost every corner of the planet. In countless places, the goat is doing serious damage to the environment by overgrazing, and it is often the culprit in the increasing desertification, which takes place across the world.

The taming and usage of the domestic goat is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Through overgrazing, domestic goats convert huge areas to semi-deserts. These pictures are from the Jhong River Valley, Mustang, Nepal (top), and Lake Tso Moriri, Ladakh, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

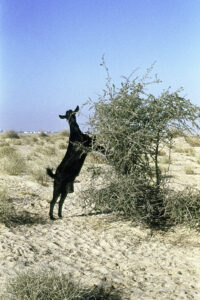

Goats are very agile. Standing on their hindlegs, these two are feeding on bushes in the Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India (top), and in Kuwait. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hemitragus jemlahicus Himalayan tahr

This species of wild goat, which lives in the temperate zone of the Himalaya, has been introduced as a hunting object to other parts of the world, including New Zealand and South Africa. However, in these countries numbers of tahrs have exploded, as they have no natural enemies here, and it has become a serious threat to the local environment through overgrazing.

An intense encounter with this animal is related on the page Travel episodes – India 2008: Mountain goats and frozen flowers.

These pictures show grazing Himalayan tahrs in the Khumbu area, eastern Nepal, where this species is common. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervidae Deer

A large number of deer species are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Deer.

Odocoileus virginianus White-tailed deer

This deer, native to North and South America, has been introduced to several European countries, and in Finland it is now considered to be a pest, which expels native deer species.

In many parts of North America, it has also spread beyond control. As far back as in 1949, in A Sand County Almanac, environmentalist Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) wrote: “I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer.”

In August 2012, The Bloomberg View published a staff editorial, entitled: “Deer Infestation Calls for Radical Free-Market Solution.”

About two months later, The Wall Street Journal ran a story, entitled: “America Gone Wild,” noting the impact of overabundant deer.

The Nature Conservancy then noted: “No native vertebrate species in the eastern United States has a more direct effect on habitat integrity than the white-tailed deer. (…) In many areas of the country, deer have changed the composition and structure of forests by preferentially feeding on select plant species.”

White-tailed deer hind, eating grass, Cathlamet, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echimyidae

Myocastor coypus Nutria, coypu

This animal is native to South America, but was introduced to North America and Europe for fur production. Over the years, numerous animals have escaped, and the species has become naturalized in many places. They are considered a pest, as they compete with – and sometimes expel – native species, erode river banks, destroy irrigation channels, and chew up house panels etc.

Feeding nutria, Avery Island, Louisiana, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This nutria is sitting on its nest, Lac de Grand Lieu, Loire Atlantique, France. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erinaceidae Hedgehogs, moonrats, and gymnures

Erinaceus europaeus European hedgehog

Various species of hedgehog are often killed by cars, and they have declined drastically in many places. In New Zealand, however, where the European hedgehog was introduced at an early stage, this species is regarded as a pest, as it competes with kiwis, five species of flightless birds of the genus Apteryx, which are restricted to New Zealand. The hedgehog eats worms and other invertebrates, which is the preferred food of these birds.

European hedgehog, killed by a car, near Kai Iwi, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Felidae Cats

Felis catus Domestic cat

Feral domestic cats are a serious threat to the wild fauna in many parts of the world. For instance, a study from 2013 suggested that free-ranging domestic cats (mostly feral) are the top human-caused threat to wildlife in the U.S., killing an estimated 1.3-4 billion birds and 6.3-22.3 billion mammals annually. (Source: S.R. Loss, T. Will & P. Marra 2013. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife in the United States. Nature Communications 4:1396)

The origin of the domestic cat is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Domestic cat, resting on a tree stump, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is resting on a discarded net under a vine, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cat on the prowl, Tunghai University Park, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This cat marks its territory by spraying urine on vegetation, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is searching for edible items in a garbage can, Sousse, Tunisia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herpestidae Mongooses

Urva auropunctata Small Asian mongoose

To control populations of rats and other rodents, this species has been introduced to many parts of the world, mostly small islands. In most places, however, it has had a negative impact on ground-nesting birds and lizards, and it is often able to out-compete smaller local carnivores. It is considered to be among the world’s one hundred worst invasive species. (Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2000)

The small Asian mongoose is widespread in Asia. These were encountered in Lake Haleji Bird Sanctuary, southern Pakistan (top), and Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leporidae Hares and rabbits

Oryctolagus cuniculus European rabbit

This species has been introduced to many countries as a hunting object. It was first brought to Britain by the Romans, following their invasion in A.D. 43, and today it is extremely common – an estimate in 2004 suggested about 40 million.

In Australia, 24 European rabbits were introduced in Victoria in 1859. The vast farmlands were an ideal habitat for the rabbits, and the mild winters allowed them to breed year-round, so they quickly spread over most of the country. Australia’s equivalent to the rabbit, the greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis), could not compete with the fast-breeding rabbits, and today it is an endangered species.

Other places of introduction include New Zealand, certain Hawaiian islands, and islands off the coast of South Africa. There are also many instances of pet rabbits, which have escaped, forming feral populations.

In countless cases, this species has done severe damage to the environment, partly through overgrazing, partly through its system of underground tunnels, and partly through competition with local wildlife. It is regarded as an invasive species in most countries.

In 1972, English author Richard Adams (1920-2016) wrote a novel, Watership Down, describing the life of a group of wild rabbits in southern England. Although the rabbits have been anthropomorphized, the story gives a fair account of the life of these animals.

The European rabbit was introduced to Britain almost 2,000 years ago, and today it is extremely common. These are sitting outside their den in the Spey Valley, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows a dark European rabbit, probably with genes from escaped pets, nibbling at a flower of common broom (Cytisus scoparius), Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muridae Old world mice and rats

Rattus norvegicus Brown rat

The brown rat originated somewhere in Asia, but has spread with humans to almost all parts of the world.

It is a serious pest, as it competes with native mammalian species, raids birds’ nests, and consumes huge amounts of cereals and other food items. Furthermore, it spreads various diseases among humans. During the Middle Ages, fleas of the brown rat were carrying bubonic plague, which in some places reduced the human population by 50 to 75%. This much feared disease was aptly named The Black Death

Brown rat, Hanoi Botanical Garden, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brown rat, caught in a trap, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mustelidae Martens etc.

Neovison vison American mink

This semi-aquatic North American mustelid has been introduced in many parts of the world for fur production, but has escaped in countless places and has become a serious threat to the native fauna, as it is a notorious predator of birds’ eggs. It is also blamed for the serious decline in populations of the European mink (Mustela lutreola), the Pyrenean desman (Galemys pyrenaicus), and the European water vole (Arvicola amphibius).

This picture is from Iceland, where teams of professional ‘mink hunters’ control mink numbers by locating as many dens as possible, removing the young and, if possible, kill the mother. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phalangeridae

Trichosurus vulpecula Brushtail possum

This cat-sized marsupial is protected in its native Australia. However, in New Zealand, where it was introduced in 1837 for the fur trade, it has become the country’s most damaging animal pest, wreaking havoc on native forests, where they eat the foliage.

Not only do possums destroy forests, they also do damage on pasture lands, causing a fall in farm production at an estimated 35 million NZ$ annually, and they also eat planted seedlings of pines and other trees. Besides, they can infect cattle with bovine tuberculosis, threatening the country’s valuable dairy industry.

Possums are found virtually everywhere on mainland New Zealand and Stewart Island, although they have been eradicated from major offshore islands since the early 1990s. Their number is difficult to accurately assess, but in the early 2000s, estimates ranged from 50 to 70 million. Their cost to the economy is considerable. In 2006, government agencies spent $111 million on possum control. (Source: teara.govt.nz/en/possums)

Numerous brushtail possums are killed by cars, as this one near Waipoua Forest, North Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procyonidae Raccoons etc.

Procyon lotor Raccoon

This animal is very common in North and Central America, from central Canada southwards to Panama. It has also become naturalized in large parts of Europe, the Caucasus, and Japan. In many places, it is regarded as a pest, plundering birds’ nests and competing with local mammals. In America, it is a nuisance in urban areas, as it will turn over garbage cans, looking for food, and spread the garbage over large areas. It also consumes food at bird feeders, if the food is not being placed out of reach.

The word raccoon was adopted by settlers in Virginia, a corruption of a Powhatan term, meaning ‘the animal that scratches with its hands’. It was variously written as aroughcun or arathkone.

This raccoon has come to a house at night, eating from a dog’s feeding bowl, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sciuridae Squirrels

Many squirrel species are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Squirrels.

Sciurus carolinensis Eastern grey squirrel

This species, by some authorities called Neosciurus carolinensis, is among the most widespread of the North American squirrels, found in the eastern half of the continent, and has also been introduced to several areas in the West. It is very common in towns, as long as there are trees, where it can take shelter from dogs and other enemies.

These animals are active throughout the year, and in autumn they store nuts and fruits in underground caches. They are not able to remember where the food was buried, but find it by smelling it under the snow. Grey squirrels are often a nuisance on bird feeders, where they consume most of the food that was intended for birds. In parks and other places, where people regularly feed grey squirrels, they become very tame indeed.

The eastern grey squirrel has been successfully introduced to South Africa, Britain, and other places. In Britain, it is regarded as a pest, as it outcompetes the native Eurasian red squirrel (S. vulgaris), which is now scarce south of Scotland. Extermination campaigns of grey squirrels have been initiated in the U.K., causing the red squirrel to increase in several places.

The specific name refers to the Carolinas. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

Eastern grey squirrel, Kew Botanical Gardens, London. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

Alopochen aegyptiacus Egyptian goose

This bird is very common in wide areas south of the Sahara and in the Nile Valley. It was considered sacred by the Ancient Egyptians, often appearing in their artwork. Due to its tameness and beauty, it was introduced to Britain in the 1700s, and later to other European countries, the United States, and New Zealand. It has become naturalized in many places in Europe, where it competes with indigenous geese and ducks. It has been declared a pest in several countries, where it may be hunted year-round, but few birds are bagged, and the species is still expanding.

The generic name is derived from the Greek alopex (‘fox’) and chen (‘goose’), alluding to the ruddy colour around the eye, and on the hindneck, back, and inner flight feathers. The specific name means ‘of Egypt’.

Egyptian geese often become very confiding and bold. This picture was taken in a campground in Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Branta canadensis Canada goose

The Canada goose is native to northern North America, but has been introduced to Britain, Sweden, New Zealand, Argentina, and other places. This species is very bold and has been able to establish populations in urban areas, where it has no natural predators. In many areas, it has been declared a pest because of its noise, droppings, and aggressive behaviour.

Canada geese, grazing on a golf course, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Canada goose was introduced to Sweden in the 1920s, and today the population is estimated to be around 100,000 individuals. – Lake Hornborga, Västergötland (upper two), and Alvesta, Kronoberg. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Passeridae Sparrows

Passer domesticus House sparrow

The house sparrow was introduced to the United States several times between 1851 and 1875, and also to New Zealand, around 1865. In both countries, it was thought that the sparrows would be able to control populations of harmful insects in cereal crops. However, they only catch insects when feeding their young, whereas the rest of the year they eat the very crops they were supposed to protect.

As early as the 1880s, the sparrow itself was regarded as a pest in New Zealand, and today it is considered a serious crop raider in large parts of North America. It also competes seriously with local species at bird feeders etc.

As early as the 1880s, the house sparrow was regarded as a pest in New Zealand, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The male house sparrow is a pretty bird, with chestnut nape and various subtle brownish colours on back and wings. This one was observed at Muriwai Beach, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man is hand-feeding house sparrows in St. James’ Park, London. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pycnonotidae Bulbuls

Various species of bulbul are described on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in the Himalaya, and Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Pycnonotus cafer Red-vented bulbul

A very common breeding bird in Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar, which has been introduced to many other parts of the world and has become invasive in several Pacific countries, including Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, and Hawaii. It has also established itself in parts of southern Arabia, New Zealand, the United States, and Argentina. It is considered to be among the world’s one hundred worst invasive species. (Source: Lowe et al., 2000. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Species: A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. The Invasive Species Specialist Group, IUCN)

Resting in a tree-like spurge of the species Euphorbia antiquorum, which grows in front of a ruined pagoda in Bagan, Myanmar, this red-vented bulbul clearly shows, why it got this name. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pycnonotus sinensis Light-vented bulbul, Chinese bulbul

This species is distributed in central and southern China, northern Vietnam, southern Japan, and Taiwan. It is one of the commonest birds in Taiwan, living in a wide variety of habitats, including secondary forest, farmland, parks, gardens, and even cities with scant vegetation.

In many parts of eastern Taiwan, large numbers of this species have been mass-released during Buddhist festivals. They have become naturalized in many areas, where they compete with – and also hybridize with – the local, endemic Taiwan bulbul (P. taivanus), causing it to have declined drastically, and already gone extinct in Yilan County.

The light-vented bulbul is one of the commonest birds in Taiwan. This one is sitting on a balcony rail in a skyscraper in the city of Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sturnidae Starlings and mynas

Acridotheres javanicus Javan myna

As a native, this species, which is also called white-vented myna, is restricted to the Indonesian islands Java and Bali. However, it has been introduced to numerous other countries as a cage bird and has escaped in many places to form wild populations, including in Taiwan, Japan, Southeast Asia, and Puerto Rico.

Today, it is very common in Singapore and Taiwan, where it out-competes local bird species, in Taiwan especially the native crested myna (A. cristatellus), which is declining.

A number of pictures, depicting Javan and crested mynas, may be seen on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Javan myna, feeding in a flower of a silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Javan myna, sitting in front of a water tower, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sturnus vulgaris European starling

In an article, European Starlings: A Review of an Invasive Species with Far-Reaching Impacts, published in Managing Vertebrate Invasive Species: Proceedings of an International Symposium, National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado, 2007, George M. Linz and others state the following:

“The introduction of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) in New York City in 1890 and 1891 resulted in their permanent establishment in North America. The successful occupation of North America (and most other continents as well) has earned the starling a nomination in the Top 100 list of ‘Worlds Worst’ invaders. Pimentel et al. (2000) estimated that starling damage to agriculture crops in the United States was $800 million yearly, based on $5/ha damage. Starlings may spread infectious diseases that sicken humans and livestock, costing nearly $800 million in health treatment costs. Lastly, starlings perhaps have contributed to the decline of native cavity-nesting birds by usurping their nesting sites.”

The starling was first introduced to Cincinnati, Quebec, and New York in the 1870s, and again in New York and Portland, Oregon, around 1890. It quickly spread across the continent, and a recent estimate puts is present number at about 150 million, living from southern Canada southwards to Central America.

As opposed to the situation in the United States, the starling is declining in large parts of Europe, mainly because of persecution in its wintering areas. In later years, the species has begun to spend the night in cities, where it is considered a nuisance because of its droppings. It also does some damage on fruit trees and other crops.

This starling is peeping out from a nesting hole, stolen from a red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) (bottom picture), Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture of a singing starling is from Denmark, where this species is a native. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Threskiornitidae Ibises and spoonbills

Threskiornis aethiopicus Sacred ibis

In Ancient Egypt, this bird was venerated as a symbol of Thoth, the god of knowledge, who is often depicted with the head of an ibis. Today, the sacred ibis is a common and popular species in zoological gardens worldwide. It often escapes, and populations in the wild have been established various places, including France, Italy, Spain, the Canary Islands, Florida, and Taiwan. These populations are a great threat to many other birds, which breed in colonies. Ibises are predators, which can ravage colonies of terns and other birds by eating their eggs and young, and they also compete for nest sites with cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis), little egret (Egretta garzetta) and others.

Sacred ibis is very common in East Africa. This picture is from the Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sacred ibis has been introduced to Taiwan, where it has escaped and is now competing with local water birds. These were photographed in Aogu Wetlands. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Achatina fulica Giant African snail

This large land snail has become a pest in many parts of the world, feeding voraciously and causing severe damage to agricultural crops and native plants, also through transmitting plant diseases. It competes with native snail taxa, and it possibly also spreads human diseases. (Source: Global Invasive Species Database)

Giant African snail, Nanhua Ecological Park, near Yujing, southern Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pomacea canaliculata Golden apple snail

This species is native to southern South America, but has been introduced elsewhere, either unintentionally, or, as in Taiwan, deliberately, with the intention of producing these snails as a substitute food source for native snails. However, their texture was too soft for consumers’ taste, and, consequently, rather than killing the snails, many were released into irrigation canals and rivers.

Being highly adaptive, they thrived and soon spread beyond control. Rice shoot are a favourite food of these snails, and, having no natural predators in Taiwan, they have become a huge menace in rice fields. Bright pink masses of snails’ eggs are often seen on concrete surfaces along river and ditches, and also on the rice plants themselves. (Source: culture.teldap.tw)

The golden apple snail is considered to be among the world’s one hundred worst invasive species. (Source: Lowe et al., 2000. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Species: A Selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. The Invasive Species Specialist Group, IUCN)

In these pictures, pink egg masses of golden apple-snail cling to a concrete embankment along a rainwater canal, and to a rice plant, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Arionidae Roundback slugs

Arion

A genus with around 18 species, found in North America and Eurasia. Many of the species are very similar and difficult to distinguish, and the number of species is disputed.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek areiones, a kind of snail or slug.

Arion vulgaris Spanish slug

The native area of this species, also known as killer slug, and formerly misidentified as Iberian slug (A. lusitanicus), is not known with certainty, but may be Spain. Since the 1950s, it has spread across much of Europe, where it is regarded as a serious pest, which can destroy a vegetable garden in the course of a few days.

Spanish slugs in a vegetable garden, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spanish slugs, eating remains of their own kind, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blattidae Cockroaches

Many species of cockroaches have been introduced by Man during his expansion to inhabit the entire planet. In countless homes, they are a true menace, consuming food, making a mess, and possibly spreading diseases to humans.

In traditional Chinese medicine, cockroaches are used against a number of ailments, such as abdominal problems, stroke, and bone fractions, and also as an anti-ageing agent. An ethnic minority in the Yunnan Province used cockroaches to treat open wounds. New research has shown that these animals contain at least nine different antibacterial substances, and one substance is able to kill AIDS virus.

For hundreds of years, cockroaches have been utilized as food in northern China. A cream, containing intestines of cockroaches and other ingredients, is applied by Chinese women to their skin to keep it young. A booming industry in the country is producing skin cream and medicine from millions of cockroaches, kept in captivity.

Cockroaches are partial to humid places and are often encountered in bathrooms, as in this picture from Luzon, Philippines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Helicidae Lung snails

Cornu aspersum Garden snail

The shell of this snail, previously known as Helix aspersa, grows to about 4 cm in diameter. It is native to the Mediterranean area, eastwards to Turkey, but has spread considerably northwards in later years, presumably due to climate change. It has also been introduced to the Americas, southern Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

It is relished as a food item in some areas, but elsewhere it is regarded as a pest in agricultural areas and gardens, especially in South Africa and California. Both places it was originally introduced as a food animal, but has become an agricultural pest, especially in citrus groves and vineyards.

Mating garden snails, St. Servan, near St. Malo, Brittany. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aizoaceae Ice plant family

Several species of this family, of which the major part are native to Southern Africa, have become established on numerous beaches around the world, often covering huge areas and expelling native species.

Carpobrotis edulis Hottentot fig

Malephora crocea Red ice plant

Two such species are hottentot fig and red ice plant, which have been introduced as an ornamental in many countries around the world. Hottentot fig is regarded as an invasive plant in numerous areas, especially around the Mediterranean, along the American Pacific coast, and in Australia. Red ice plant has been widely planted along Californian highways in areas prone to fire, as its succulent leaves do not easily catch fire. However, it soon escaped, spreading to numerous beaches in California and Baja California, where it has become a noxious weed, covering large areas.

Hottentot fig, Mac Kerricher State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red ice plant, Border State Park, south of San Diego, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amaranthaceae Amaranth family

Alternanthera

Members of this genus are characterized by their whitish, papery flowers. The number of species varies enormously, from 80 to 200, depending on authority. These plants, also known as joyweed or Joseph’s coat, mainly stem from South America, with some species native to Asia, Africa, and Australia. Many species have been accidentally introduced elsewhere, and several are regarded as noxious weeds.

Alternanthera philoxeroides Alligator weed

Alternanthera sessilis Sessile joyweed

These two South American species have been spread to more than 30 countries and are the worst invaders of the genus. Both are pioneer plants, growing in a wide range of habitats, including marshes, margins of streams, damp forests, and open disturbed areas. In many places, they have become a huge problem in water courses, as they often block the flow of water. They may also become agricultural weeds in fields. They are listed as invasive in a number of countries, including United States, New Zealand, China, India, and South Africa.

Sessile joyweed is very common in Taiwan. These pictures show a large growth on the shore of the Agongdian River, south-western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sessile joyweed also grows in cities. This specimen has sprouted in a crack in a pavement, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alligator weed may be told from sessile joyweed by its stalked inflorescences. This growth was encountered on a lawn in a city park, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amaryllidaceae Amaryllis family

Allium triquetrum Three-cornered leek

This species is also called three-cornered garlic or onion weed, the specific name and two of the English names referring to its triangular flower stalks. It is native to coastal areas of north-western Africa and south-western Europe, from the Iberian Peninsula and southern France eastwards to Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily, and also Madeira and the Canary Islands, growing in grasslands, on river banks, and along roads.

It has been introduced to a number of other countries, including England, Ireland, Turkey, New Zealand, and Australia, and is regarded as an invasive in several countries.

Three-cornered leek is very common along roads in New Zealand, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Allium ursinum Ramsons

Ramsons is hardly a native of northern Europe, but was probably introduced by monks during the Middle Ages as a nourishing herb. Today, it is very common in forests and groves here, often becoming an invasive, which dispels other plant species.

As early as 1741, the famous Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) noticed this phenomenon on his journey to the Swedish islands Öland and Gotland. He relates the following: ”The farmers told me that where this plant is growing, it dispels other species. We had clear evidence of this fact, because where ramsons was growing there were no other plants.” (Source: C. Linnæus 1745. Carl Linnæi Öländska och Gotländska Resa, förrättad År 1741 (‘Travels by Carl Linnæus in Öland and Gotland 1741’), new ed. Wahlström & Widstrand 1975)

A popular name of ramsons is bear’s garlic. According to the booklet Chrut und Uchrut (in English called Herbs and Weeds – a useful booklet on medicinal herbs), written in 1911 by Swiss priest and herbalist Johann Künzle (1857-1945), this name was applied hundreds of years ago by people, who noticed that bears, still weak and emaciated after a long winter hibernation, would gorge themselves on leaves of ramsons and thus regain their strength. This fact is reflected in the specific name, from the Latin ursus (‘bear’), applied in 1758 by Linnaeus.

In his book Carl Linnæi Skånska Resa, förrättad År 1749 (‘Travels by Carl Linnæus in Skåne 1749’, new ed. Wahlström & Widstrand 1975), Linnaeus mentions that a local name of ramsons is Sancta Brittæ lök (‘Saint Britta’s onion’), named after Birgitta Birgersdotter (‘Holy Birgitta’), a Swedish saint, born around 1303, who died in Rome 1373 during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The following year, her earthly remains were brought back to Sweden and buried in Vadstena Abbey, near Linköping.

This picture is from the island of Bornholm, Denmark, where ramsons is very common and has become the dominating plant in several smaller forests. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apiaceae Umbellifers

Heracleum mantegazzianum Giant hogweed

This large plant, often called giant cow-parsley, and in Latin Heracleum pubescens, is native to the Caucasus Mountains and Central Asia. In the 1800s, it was introduced as an ornamental to Europe, and later to the United States and Canada. It has become naturalized in many areas, especially wetlands, and due to its vigorous growth it often expels native species. Furthermore, its sap is toxic to the human skin, causing inflammation and blisters. In many countries, its spreading is inhibited by using herbicides – the only known efficient means to control this species.

Where undisturbed, giant hogweed grows to huge dimensions – note the person in the centre of this growth from northern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The spreading of giant hogweed may be inhibited by spraying with herbicides. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apocynaceae Dogbane family

Vinca minor Lesser periwinkle

This creeping plant is probably native to central and southern Europe, from Portugal and France eastwards to the Caucasus, northwards to the Netherlands and the Baltic States. However, its original distribution is difficult to ascertain, as it was introduced widely in Europe at an early stage, cultivated as an ornamental.

Lesser periwinkle was first introduced to North America in the 1700s. It has since escaped cultivation in many places throughout the eastern and north-western United States, often invading natural areas and displacing native species. It is also often an invasive in northern Europe and elsewhere.

The word periwinkle, which was first used in English in 1922, was taken from the flower colour of this plant. It is a shade of lavender blue.

In this picture, lesser periwinkle is covering the entire forest floor of a copse in Oyster Bay Cove, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large growth of lesser periwinkle in a forest, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zantedeschia aethiopica White calla

This spectacular plant, also called arum lily, is native to southern Africa. However, it is widely cultivated in warmer regions of the world, where it often escapes. It has become naturalized in a number of places, including other African countries, New Zealand, Madeira, coastal California, and Australia. In the latter country, it has been classified as a pest.

White calla often escapes cultivation in New Zealand, where these pictures were taken, in a ditch near Mokau River (top), on a beach near Omata (centre), and at Whanganui River. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ageratum conyzoides Goat-weed

Ageratum houstonianum Mexican blueweed

These species are both native to Central and South America, but have become naturalized worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas. Both are regarded as invasive weeds in numerous countries around the world, in Africa, Southeast Asia, China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

These plants are described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry, including their medical usage.

Goat-weed, Marsyangdi Valley, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mexican blueweed is very common in Taiwan, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bidens pilosa Downy bur-marigold

This plant is a pan-tropical and -subtropical weed of unknown origin, which has become a pest in many places, expelling native species. One isolated plant can produce over 30,000 hooked seeds, which are readily spread by sticking to animals’ furs, socks, trousers, etc. This way of seed dispersal has given it names like beggar-ticks, stickseed, farmer’s friend (ironic!), needle grass, Spanish needles, stick-tight, cobbler’s pegs, Devil’s needles, and Devil’s pitchfork. Other names include blackjack and hairy bidens.

A South African website, farmersweekly.co.za/animals/horses/beware-those-blackjacks, says: “The common blackjack is not only an irritant to horses, (but) can cause them injury. (…) There can be few of us who have not spent ages picking them off our clothes after walking through the veld to catch horses in the early winter. Blackjacks that become entangled in the forelock of a horse can be a great irritant, and the animal will toss its head, if you try to remove them. The spines can injure the eyes, so it’s better to clip the forelocks short. Blackjacks can also get caught up in the long hair behind the fetlocks and pasterns, causing chronic irritation and lameness.”

This species is reported to be a weed of 31 crops in more than 40 countries, Latin America and eastern Africa having the worst infestations. (Source: cabi.org/isc/datasheet/9148)

However, downy bur-marigold is not only a troublesome weed, it also has medicinal properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, it has been used for a large number of ailments, including influenza, colds, fever, sore throat, appendicitis, hepatitis, malaria, and haemorrhoids. Due to its high content of fiber, it is beneficial to the cardiovascular system, and it has been used with success in treatment of diabetes.

These pictures are from Taiwan, where downy bur-marigold is highly invasive, covering huge areas. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Downy bur-marigold, covering the ground in a banana plantation, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The hooked seeds of downy bur-marigold readily spread by sticking to animals’ furs, socks, trousers, etc. This picture was taken at Pokhara, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carduus nutans Musk thistle

This plant, also called nodding thistle, is native to parts of Eurasia and North Africa, but has spread to many other areas of the world. It grows in open areas, preferably on disturbed ground, such as fallow fields and road sides. In the early 19th Century, it was introduced to North America, where it quickly became a nuisance in agricultural areas. It is declared a noxious weed in the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Musk thistle, Devil’s Tower National Park, Wyoming, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cirsium arvense Creeping thistle

This Eurasian plant, in America called Canada thistle, is a most troublesome weed in most cooler parts of the world. As far back as 1863, Danish research showed that a large thistle can produce about 80 flowerheads in one season, and as flowerheads on average contain 120 flowers, one single plant is able to produce about 10,000 seeds per year!

However, the success of this plant is not only due to its production of seeds. Its many spines cause many animals to avoid eating it, but the smartest ‘trick’ is its root system. The underground stem, which is situated at a depth of 20 to 40 cm, grows lively in all directions, and just a tiny bit of underground stem is able to produce a large colony of plants, sending up stems at regular intervals. Some shoots grow downwards to a depth of a couple of metres, where the ground is always humid. In this way, the plant always has a secure source of water, no matter how dry the weather may be. Also, an even deep-ploughing plough does not reach the deepest stems.

If you want to control creeping thistle in your garden, the best way is to exhaust it by constantly removing the green shoots, as soon as they appear, and keep doing it. As Danish poet Thomas Kingo (1634-1703) expressed it: “Evil weed does not perish by itself.” And a proverb by Danish author Peder Syv (1631-1707) says: “Evil weeds grow fastest and perish latest.” (Source: H. Knudsen 2014. Fortællingen om Flora Danica. Lindhardt & Ringhof, in Danish)

In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes: “(…) it is, perhaps, the worst weed of the entire United States. (…) Its seeds serve as food for goldfinches and sparrows, but even this good turn is offset by the fact that the birds, in getting their food, set free the winged seeds, and wherever those seeds fall trouble begins. The plant is outlawed in every northern State; thirty-seven States in all legislate against this rogue, but outlawing it has had very little effect upon it.”

Fallow field, full of creeping thistles, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Creeping thistle in a field of barley, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One individual creeping thistle can spread up to 10,000 seeds per season. – Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erigeron canadensis Horsetail fleabane

This plant, also called Canadian fleabane, and in Latin sometimes Conyza canadensis, is native to North America and parts of Central America. It has been accidentally introduced to large parts of the world, in many places becoming a serious pest, especially in Europe and Australia, but also in its native North America. It prefers to grow in undisturbed areas and is particularly troublesome in newly established plantations, where it is able to resist herbicides, growing to 3 m tall, thus depriving planted species of nutrients and sunlight.

This plant contains an oil with a turpentine-like smell, which, supposedly, should deter fleas, hence its common name. Another popular name is bloodstanch, given by herbalists, who claim that an extract from leaves and flowers arrests haemorrhages from the lungs and alimentary tract.

Horsetail fleabane also grows in cities, described on the page Plants: Urban plant life.

This horsetail fleabane, observed in a graveyard in the city of Taichung, Taiwan, is almost 2 m tall. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Denmark, where this picture was taken, horsetail fleabane is a serious pest in young coniferous plantations. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruiting horsetail fleabane, Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Galinsoga parviflora Potato weed

Galinsoga quadriradiata Shaggy soldier

Potato weed is native to South America. In 1796, it was brought from Peru to Kew Gardens, London. Later, it escaped and quickly formed wild populations. Today, it has been spread to most parts of the world. As its common name implies, it is often a weed in potato fields.

Leaves, stem and flowers are edible, and the subtle flavour, reminiscent of artichoke, develops after being cooked. It is also dried and ground into powder for usage in soups. In Nepal, juice of the plant is applied to wounds.

Shaggy soldier is probably native to Mexico, but has become naturalized countless places around the globe. It is very often a troublesome weed in vegetable gardens, but in Mexico and China it is used as a pot herb or in salads.

The genus was named in honour of Ignacio Mariano Martinez de Galinsoga (1756-1797), director of the Royal Botanical Garden in Madrid, and physician to the Spanish Queen consort Maria Luisa de Parma. In Britain, the generic name was corrupted to gallant soldiers.

Potato weed, Shivapuri-Nagarjun National Park, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shaggy soldier, growing as a weed in a vegetable garden, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mikania cordata

This plant, sometimes called African mile-a-minute or heartleaf hempvine, is native to various tropical areas of Africa and Asia. It is a climber, which may reach a length of 10 m, growing from sea level to elevations of at least 1,700 m. In many countries, it is regarded as an invasive, noxious weed, but in some areas local people consume its leaves, and it is also planted as a means to control soil erosion.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘heart-shaped’, which refers to the leaves.

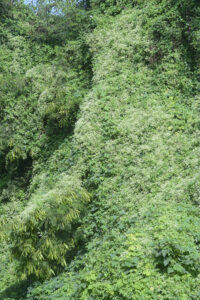

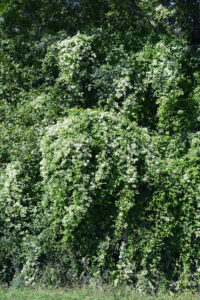

Mikania cordata is very common in Taiwan. In these pictures from Tunghai University Park, Taichung, it almost covers a bamboo growth (above), and a Bougainvillea. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Solidago gigantea Giant goldenrod

Giant goldenrod is an American plant, which was introduced to Europe as an ornamental in the mid-1700s. The first naturalized populations were observed about a hundred years later, but it was not considered an invasive before the 1950s. Since then, it has spread rapidly, often expelling native vegetation over large areas, and today it is regarded as an invasive in all European countries.

The generic name is derived from the Latin solido, meaning ‘to join’, or ‘make complete’. Formerly, several species of goldenrod were reputed to be able to heal wounds.

Large growth of giant goldenrod, photographed on the island of Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tithonia diversifolia Mexican sunflower

This species, also known as tree marigold, is native to Mexico and Central America, but has been introduced to many tropical and subtropical countries around the world as an ornamental plant. Due to its vigorous growth, it is cultivated many places as green fertilizer, and it is also used medicinally.

It is a large sunflower-like plant with a woody, erect stem, growing to 3 m tall. The leaves are ovate in outline, toothed and pointed, usually to about 20 cm long, occasionally to 40 cm. As its Latin name implies, their shape is diverse, mostly with 3-7 lobes, but sometimes simple. The large, fragrant flowers are bright yellow with an orange centre, to 15 cm across.

Due to its tolerance to heat and drought, Mexican sunflower often invades fallow lands, forming dense stands that outcompete native vegetation. It is regarded as invasive in at least 50 countries.

In Taiwan, where these pictures were taken, Mexican sunflower is very common, often forming large growths in open places. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mexican sunflower with seedheads, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Balsaminaceae

Impatiens glandulifera Himalayan balsam

As its name implies, this large species, growing to 2 m tall, is native to the Himalaya, distributed from Pakistan eastwards to Uttarakhand, at altitudes between 1,800 and 4,000 m.

It is widely cultivated and has become naturalized in many European countries, North America, New Zealand, and elsewhere. It is considered a noxious weed in many countries, often forming large stands, which expel native species.

Himalayan balsam with rain drops, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Impatiens parviflora Small-flowered balsam

The original range of this plant is probably mountains of Central Asia, but it has become widely naturalized elsewhere. It is regarded as an unwanted weed in many countries, often dispelling native plants in damp and shady forests.

When cooked, the leaves are edible, and the seeds can be consumed raw or cooked. Medicinally, it has been used for treatment of warts, ringworm, and nettle stings, and also to relieve an itchy scalp.

Small-flowered balsam, covering huge areas in a forest, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, small-flowered balsam has conquered a forest track, eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brassicaceae Cabbage family

Alliaria petiolata Garlic mustard

This plant, native to Eurasia and North Africa, was introduced to North America as a spice herb around 1860. Since then it has spread to most of the states of the U.S., and to Canada as well. Its natural enemies of the Old World, such as fungi and insects, are not present in North America, which leads to a much higher seed production.

Garlic mustard has invaded numerous forests, where it is able to dominate the understorey, hereby expelling native plants. It is listed as a noxious species in at least 9 American states.

This picture is from Denmark, where garlic mustard is a native. Nevertheless, it has also been expanding in this country during the last 50 years. The plant with the red flowers is red campion (Silene dioica). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mutarda nigra Black mustard

This species was previously known as Brassica nigra, but now constitutes the only member of the genus Mutarda. It is probably a native of southern Europe, the Middle East, and the Indian Subcontinent, but as it has been cultivated for thousands of years, this is difficult to say with certainty. It is grown for its seeds, from which mustard is produced.

At an early stage, it was introduced to many other parts of the world and has become naturalized in numerous countries. It is classified as invasive in California, Hawaii, and some of the Great Lakes states in the U.S., in New Zealand, and on off-shore islands in Chile.

Black mustard, growing on a beach in Montaña de Oro State Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Caprifoliaceae Honeysuckle family

Lonicera japonica Japanese honeysuckle

This climber, native to eastern Asia, including China, Taiwan, Japan and Korea, has been imported into numerous countries as an ornamental and has become naturalized many places, including the United States, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, as well as a number of Pacific and Caribbean islands.

Due to its vigorous growth and production of numerous seeds, it is extremely difficult to control. In many U.S. states, it is classified as a noxious weed, and it is banned in New Hampshire. In New Zealand, the National Pest Plant Accord has declared Japanese honeysuckle “an unwanted organism”.

Japanese honeysuckle, photographed in Taiwan, where it is indigenous. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Japanese honeysuckle, naturalized in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celastraceae Staff-tree family

Celastrus orbiculatus Oriental bittersweet

This climber, native to eastern Asia, was introduced to North America from China around 1860 as an ornamental, but has since escaped cultivation and become widely naturalized. In the eastern part of the continent, it is a menace, affecting the ecology in about 33 states. Birds and other animals relish its fruits, which has contributed to its spreading.

It closely resembles the native American bittersweet (C. scandens), with which it readily hybridizes, thus threatening the gene pool of this local species.

Flowering oriental bittersweet, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, oriental bittersweet is enveloping two conifers near Lenox, Massachusetts. In the background autumn foliage of sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and other trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Commelinaceae Dayflower or spiderwort family

Tradescantia zebrina Wandering Jew

This plant, native to Mexico, Central America, and Colombia, was named for John Tradescant, a Royal British horticulturist in the 17th Century. It is a popular garden plant, which, however, has a tendency to spread, mostly in disturbed forests, but also in native forests of St. Lucia in the West Indies, and in Hawaii. Stems, which have broken off, are able to take root, and, over the years, create veritable carpets on the forest floor.

Today, it is regarded as an invasive in many places, including South Africa, Brazil, Galapagos Islands, St. Lucia, Hawaii, and Taiwan. In South Africa, all trade in seeds and cuttings of the species is prohibited.

Wandering Jew covers large areas in Malabang National Forest, Taiwan, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Convolvulaceae Morning-glory or bindweed family

Many members of this family are described on the page Plants: Morning-glories and bindweeds.

Convolvulus arvensis Field bindweed

This Eurasian species, which twines around other plants to compete for sunlight and nutrients, was probably accidentally introduced into North America around 1740. Today it is regarded as one of the world’s worst weeds, which invades agricultural fields, reducing crop yields by 20-80%. In 1998 alone, it was estimated that crop losses due to field bindweed in the U.S. exceeded 377 million $.

In America, popular names of this species include Creeping Jenny, alluding to its invasive nature. In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes: “Creeping Jenny is one of the meanest of weeds. That name aptly describes it. A whispering little hussy that creeps in and spoils everything. The weed needs no other name than this, but it has several others (…) hedge bells, corn-lily, withwind, bellbine, lap-love, sheep-bine, corn-bind, bear-bind, and green vine.”

Large growth of field bindweed along a road, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Field bindweed, growing on a beach, Bornholm, Denmark. Beaches are among the natural habitats of this species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ipomoea cairica Railroad creeper

This plant, also known as coast morning-glory or mile-a-minute vine, is believed to be a native of Tropical Africa, but today it has a very wide distribution in tropical and subtropical areas around the world.

It is capable of very rapid growth, sometimes completely entwining trees and bushes, but is also able to creep along the ground. It is regarded as an invasive in many areas, including eastern Australia, southern China, and Taiwan.

These pictures are from Taiwan, where railroad creeper is extremely common. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dennstaedtiaceae Bracken family

Pteridium aquilinum Bracken

Bracken has an almost cosmopolitan distribution, found in most temperate and subtropical regions of the world. Areas, which have been utilized for farming or grazing, and then abandoned, are readily invaded by this species, which can cover huge areas, hindering growth of other species.

The forest on this mountain top north of Songea, Tanzania, has been felled, and the clearing has been completely taken over by bracken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Despite having withered, these bracken still almost hide young trees in a coniferous plantation in Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dense growth of bracken, Mols Bjerge, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elaeagnaceae Oleaster family

Elaeagnus umbellata Japanese silverberry

This species, also known as autumn olive, is indigenous to East Asia, from the Himalaya to Japan. As early as c. 1830, it was introduced into the United States, and in the 1950s, it was widely promoted as a splendid species to control erosion in environmentally disturbed areas, at the same time providing food for wildlife.

However, it soon became an invasive species, displacing native sun-loving plants by creating dense shade. One bush can produce up to 200,000 seeds a year, and its nitrogen-fixing root nodules allows it to grow in even the poorest soils. Attempts to remove bushes by cutting and/or burning are in vain, as it easily sprouts from the roots. Birds devour the seeds, thus aiding in the dispersal of the species.

Under the Alberta Weed Control Act of 2010, Japanese silverberry is characterized as a “prohibited noxious weed”.

Japanese silverberry, New Jersey, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Equisetaceae Horsetail family

A family of spore-bearing plants, containing only a single genus, Equisetum, found in most parts of the world, except Australia and Antarctica.

These plants, comprising about 18 species, have a hollow, jointed, silica-containing stem with 3-40 longitudinal grooves. The leaves, often reduced to scales, are arranged in whorls at each joint. There are two distinct types, of which one has brown, fertile spring shoots and green, sterile summer shoots, which supply the photosynthesis. The other group has only green summer shoots, with terminal sporangies. They vary from dwarf plants, 20 cm tall, to giants up to 8 m tall.

The generic name is from the Latin equus (‘horse’), and seta, which has several meanings, including ‘rough’, ‘brush’, or ‘hair’. The latter word can refer to the rough, silica-containing stems of these plants, but together with equus, the word means ’horse hair’. With a bit of imagination, a bunch of drying stems do resemble a horsetail.

Equisetum palustre Marsh horsetail

This species is widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, from sub-Arctic areas southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, and southern China, and in America southwards to northern United States.

It is very common in humid meadows, where it often forms large colonies, which are much feared among farmers, as it is toxic to grazing animals, causing lack of coordination in horses, and lameness in cattle and sheep. In many places it is regarded as an invasive.

Marsh horsetail belongs to the group of horsetails, in which the sporangia are clustered in so-called strobili at the tip of the stem.

Lamb of Gotland sheep in a large growth of marsh horsetail with dew drops, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marsh horsetail with sporangia, Funen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ericaceae Heath family

Rhododendron ponticum Pontic rhododendron

During his travels in the Middle East 1700-1702, French physician and botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) encountered a species of rhododendron, growing on the Black Sea coast in the area of Pontus, in present-day north-eastern Turkey and Georgia. For this reason, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named it Rhododendron ponticum (‘Pontic rhododendron’).

The nominate subspecies is native to the Caucasus, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Bulgaria, whereas small populations of subspecies baeticum are distributed in south-western Spain and Portugal.

In 1763, Pontic rhododendron was introduced to Britain as an ornamental, and it was also planted as cover for game birds. It quickly became naturalized, spreading by suckers on the tips of the branches. Today, in England, Wales, and Ireland, it is a widespread menace, which has colonized numerous hillsides, moorlands, and shady woodlands, often replacing local plant species.

Many pictures, depicting other rhododendron species, may be seen on the page Plants: Rhododendrons.

Pontic rhododendron, photographed near the town of Espiye, on the Black Sea coast, northern Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Euphorbiaceae Spurge family

Triadica sebifera Chinese tallow-tree

This smallish tree, formerly called Sapium sebiferum, is native to China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and northern Vietnam.

The specific name means ‘wax-bearing’, referring to the tallow, which coats the seeds. Candles and soap are made from this wax, and in the Far East, the leaves are used in traditional medicine for treating boils. The sap and leaves are reputed to be toxic, and decaying leaves from the plant are toxic to other plants, inhibiting their growth.

Because of the tallow, this tree was introduced into the United States in the 1700s, and in the 1900s, it was widely planted along the Gulf Coast by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in an attempt to establish a soap-making industry. However, it soon spread beyond control and is today regarded as a serious pest in south-eastern U.S., which expels native plant species. It is also regarded as invasive in India and Australia, and in Taiwan, despite being indigenous here.

In winter, the leaves of Chinese tallow-tree turn various gorgeous shades of red, varying from orange to wine-red. A collection of pictures, depicting this foliage, is shown on the page Autumn.

Chinese tallow-tree is very common in Taiwan. Its fruits are white. These pictures show fruiting trees in Central Taiwan Science Park, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Winter foliage of Chinese tallow-tree, Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fabaceae Pea family

Abrus precatorius Crab’s eye

The name crab’s eye stems from the pattern on the colourful red-and-black seeds of this plant, which has many other popular names, most of which also refer to the seeds.

It is possibly a native of India, but at an early stage, it was introduced to many other countries, and today it has a pan-tropical and -subtropical distribution. In many areas, including Belize, West Indies, United States, Hawaii, and Polynesia, it is proclaimed an invasive weed.

The role of crab’s eye in folklore and medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Crab’s eye, Dehra Dun, Uttarakhand, northern India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cytisus scoparius Common broom

In northern Europe, and also in parts of North America, most common brooms are of South European origin, imported as ornamentals. They often escape, in many places becoming invasive, dispelling native vegetation. Genetically, they also pollute the original, low and creeping variety of broom, which is today very rare. In Denmark, for instance, it is only found in a few moors and dunes in western Jutland.

The role of common broom in folklore and medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

In this picture from central Jutland, Denmark, common broom grows together with another alien invasive plant, the large-leaved lupine (Lupinus polyphyllus), which is a native of America. The latter is presented elsewhere on this page. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Here, a large growth of common broom has been established in the moorland Hammerknuden, northern Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Today, the original North European form of common broom, which is low and creeping, is only found in a few moors and dunes in western Denmark, here at Sønder Vosborg Hede, Jutland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leucaena leucocephala White leadtree

This species, also called white popinac, is a member of Caesalpinoideae, a subfamily of the pea family. It is native to southern Mexico and parts of Central America, but has become naturalized throughout the tropics and parts of the subtropics.

White leadtree is a prolific species, forming dense growths, often dispelling native vegetation. It is regarded as an invasive in numerous countries, including Taiwan, Hong Kong, several Pacific islands, northern Australia, southern United States, Puerto Rico, and parts of Europe and South America. By the Invasive Species Specialist Group (IUCN) it is considered to be among the world’s one hundred worst invasive species.

White leadtree is extremely common in Taiwan, where it has taken over large tracts of fallow land. This picture from Taichung shows a large flowering growth. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows the reddish seed pods of white leadtree, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The flowers are much visited by bees. This picture is from Cigu Wetlands, Tainan, south-western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lupinus polyphyllus Large-leaved lupine

Lupines, comprising more than 200 species, are mainly distributed in the Americas, but also some species around the Mediterranean and in North Africa. The generic and common names stem from the Latin lupinus (‘wolfish’), referring to an old belief that these plants would ravenously exhaust the soil. (Source: Collins English Dictionary)

A native of western North America, the large-leaved lupine is a pretty garden plant, which readily escapes cultivation, forming large growths. It is regarded as an invasive species in many countries, including New Zealand, Finland, Norway, Switzerland, Czech Republic, and Lithuania.

Evening picture from a forest near Sankt Peter am Kammersberg, Austria. Large-leaved lupine has completely taken over a large clearing. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another large growth of large-leaved lupine, Samsø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pueraria montana ssp. lobata Kudzu

The kudzu vine, or Japanese arrowroot, is a native of eastern Asia, but was introduced to the United States in 1876 as a means to curb soil erosion. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was cultivated in an area covering more than a million acres. However, it soon escaped, spreading along roadsides to most of the eastern and south-eastern states, and also to southern Canada. It grows vigorously, often completely enveloping indigenous vegetation and over time suffocating it. Today, kudzu is regarded as a serious pest in several countries, including the United States and New Zealand. In the latter country, it has been declared an “unwanted organism”.

Kudzu is much utilized in Chinese traditional medicine, described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

In this picture, kudzu has invaded an empty plot in the city of Da Nang, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These pictures are from Taiwan, where kudzu is a native. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ulex europaeus Common gorse

Due to its pretty flowers, this European species has been introduced to many other areas around the world, including North and South America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. It readily escapes cultivation and has become a serious invasive in numerous areas, notably the western United States, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, and Chile.

To some extent, its spreading can be controlled by the gorse spider mite (Tetranychus lintearius) and the gorse seed weevil (Exapion ulicis).

In English, the earliest known use of the word ulex is from 1753. It was mentioned by Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.), when he described gold mining in north-western Iberia. Thus, the name Ulex may allude to the golden-yellow flowers of members of the genus.

A close relative, the western gorse (U. gallii), is described on the page In paraise of the colour yellow.

Large growths of common gorse have taken over these bluffs near Kai Iwi, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In California, common gorse is a very serious pest, here photographed at Tomales Bay. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common gorse, Jughandle State Park, California. The upper picture shows prisoners, clearing a large growth. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meliaceae Mahogany family

Melia azedarach Persian lilac

The origin of this tree, also known as Chinaberry or bead tree, is disputed. Some authorities claim that it is native to Iran and the Indian Subcontinent, others include Indochina, Indonesia, and Australia. Due to its beautiful flowers and fruits it has been widely planted elsewhere. It readily spreads and is regarded as an invasive plant in various places, including North America, East Africa, some Pacific Islands, New Zealand, and Australia.

It is mostly a small tree, but may sometimes reach a height of 35 m. The bark is brown with narrow vertical or slanting grooves. The leaves are long-stalked, dark green, to 50 cm long, twice or thrice pinnate, with ovate or elliptic leaflets, to 7 cm long, margin toothed. The flowers are star-shaped, pink or lilac, to 1.8 cm across. They are arranged in clusters, growing from the leaf axils. The fruit is a drupe, about 8 mm across, light yellow at maturity, often hanging on the tree all winter, unless they are eaten by birds. They are poisonous to humans, but the birds are not affected.

The specific name stems from Persian azad dirakht, meaning ‘noble tree’.

The pictures below are all from Taiwan, where this species is commonly planted as an ornamental tree.

The name Persian lilac refers to the pretty flowers. – Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another name of Persian lilac is bead tree, referring to the fruits. – Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Broussonetia papyrifera Paper mulberry

This small tree is native to East and South Asia and possibly also to some Pacific islands. It thrives in a wide range of habitats and climates, readily growing in disturbed areas. It is dioecious, and when male and female plants grow together, and seeds are produced, it spreads rapidly. Birds and other animals eat the fruits and thus help dispersing the species. It can also form dense stands via its spreading root system.

As its name implies, fibres of paper mulberry were formerly utilized to produce paper, and in parts of the Pacific, cloth is still made from the bark. The wood is used for making furniture and utensils, and the roots can be used as rope. The orange fruit is fleshy and edible, and the leaves can also be eaten when cooked. Fruit, leaves, and bark were formerly used in traditional medicine.

In the United States, paper mulberry was introduced as a fast-growing shade tree, but due to its vigorous growth it soon began to displace native species, and today it is considered to be an invasive in the south-eastern states. In Pakistan, it is regarded as one of the worst weeds, and it is a highly significant invasive plant on the pampas of Argentina. It is also one of the most dominant invasive species in forests of Ghana and Uganda.

Dense growths of paper mulberry cover abandoned plots near Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paper mulberry is very common in Taiwan, even in cities, where it pops up in cracks everywhere. In this picture, it grows along a sidewalk in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The leaf shape of paper mulberry varies from almost entire to deeply indented. – Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male inflorescence of paper mulberry with copious pollen, which has fallen onto a leaf, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The orange fruit is fleshy and edible, and the leaves can also be eaten when cooked. – Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Onagraceae Evening-primrose family

An almost worldwide family with 22-24 genera and about 650 species of herbs or shrubs, rarely trees.

The family name is derived from Onagra, the original name of evening-primroses (today called Oenothera). The term Onagra was first used in botany in 1587, meaning ‘(food) of onager’, an Asiatic species of wild ass (Equus hemionus). It is most odd that this name was applied to evening-primroses, which were originally purely American plants.

Ludwigia Primrose-willowherb

This is a genus of about 82 species of mainly aquatic plants, found mostly in the Tropics.

The genus was named by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in honour of German botanist Christian Gottlieb Ludwig (1709-1773). However, it seems that Ludwig was not too happy about this honour. Maybe the flowers of this genus were not pretty enough? Or he didn’t like aquatic plants to be named after him?

Ludwigia hyssopifolia Narrow-leaved primrose-willowherb

This plant, also known as narrow-leaved water-primrose, may grow to 2 m, sometimes 3 m, tall, upper stem ribbed, often becoming woody at the base. The leaves are narrow, lanceolate, to 10 cm long and 3 cm wide. Its flowers are small, petals yellow, sometimes fading to orange, to 3 mm long and 2 mm wide.

The origin of this species is not clear, but today it is a very widespread weed of rice fields and wetlands in tropical and subtropical areas around the world.

The specific name refers to the likeness of its leaves to those of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis), of the mint family (Lamiaceae).

Narrow-leaved primrose-willowherb may grow to 3 m tall. This one has sprouted in a drainage canal in Tunghai University Park, Taichung, Taiwan. The picture was taken in the morning, and steam is rising from the water. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The flowers of narrow-leaved primrose-willowherb are quite small, with 4 petals. This picture also clearly shows its narrow leaves. – Fazi River, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ludwigia octovalvis Mexican primrose-willowherb

Despite its name, the native area of this species is unknown, and today it is found in most tropical and subtropical areas of the world. It easily becomes naturalized and is regarded as an invasive in some countries. The stem is downy, without grooves, and the leaves are quite variable, elliptic, ovate, linear, or lanceolate. The flowers usually have 4 large yellow petals, sometimes 5.

It closely resembles water primrose-willowherb (L. peploides), which, however, usually has elliptic or ovate leaves and 5 overlapping petals.

Large growth of Mexican primrose-willowherb in a drainage canal, Taichung, Taiwan. The plant with white ray florets is downy bur-marigold (Bidens pilosa), described above at Asteraceae. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, Mexican primrose-willowherb grows in a drainage canal in Tunghai University Park, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of Mexican primrose-willowherb usually has 4 petals, but in this case it has 5. – Han River, Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oxalidaceae Wood-sorrel family

Oxalis pes-caprae African wood-sorrel

This pretty plant is a native of South Africa, but has been accidentally introduced to many corners of the planet. It is regarded as an invasive in many places, including North America, Israel, Australia, and several European countries.

In these pictures, African wood-sorrel has displaced the natural vegetation in this littoral meadow near Cape San Martin, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Poaceae Grass family

Arundo donax Giant reed

This huge grass is often to 6 m tall, sometimes even to 10 m. It is native from Turkey, Jordan, Arabia, and Kazakhstan eastwards across central and southern Asia to Japan, but has become widely naturalized elsewhere.

In western United States it has been extensively planted as a means to control soil erosion, and as a biomass plant, but it often escapes and has become highly invasive in numerous places, especially along rivers, where it often displaces the natural vegetation.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for several reed species with stiff, bamboo-like stems. The specific name is the Ancient Greek name of this species.

In this picture, giant reed grows on a bluff in Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, Big Sur, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Avena fatua Wild oat

This plant is believed to have originated in Central Asia and has been associated with the cultivation of oats (A. sativa) and other cereals since the early Iron Age. Wild oat also has edible seeds, but is unsuitable for cultivation due to the fact that as soon as the kernels are ripe they fall to the ground, as opposed to the cultivated oat.

In former days, wild oat was so numerous that in certain areas it would lower the yield of crops by 40%. In Denmark, it was declared an outlaw in 1956, to be “removed from all cultivated and un-cultivated areas by the owner or the user.” Before the introduction of chemical herbicides, the plants had to be removed by hand, which was a very time-consuming task. An advantage was that wild is often taller than the surrounding crop, making it relatively easy to spot.

Today, wild oat is still is a serious pest in many countries, and as it is highly adaptable to various environments, it has become naturalized in numerous places. It is regarded as being among the world’s worst agricultural weeds. (Sources: D.P. Jones (ed.) 1976. Wild oats in world agriculture. An interpretative review of world literature. Agricultural Research Council. London; and L.G. Holm et al. 1977. The World’s Worst Weeds. Distribution and Biology. University Press of Hawaii)

Wild oat, naturalized in Crystal Cove State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cenchrus setaceus Purple fountain grass

This species, by some authorities called Pennisetum setaceum, forms large clumps of slender, arching leaves, to 60 cm long and 5 mm wide. Leaf sheaths are usually smooth, but sometimes has white hairs along the margin. The inflorescence is a dense, cylindrical, bristly spike, to 35 cm long, the colour varying from light green when young, to white, pink, buff, or purple when maturing.

It is native to northern and eastern Africa, Arabia, and the Near East, but has become naturalized in many other places, and is often regarded as an invasive species, which is a threat to native species. It also tends to increase the risk of wildfires, to which it is well adapted, thus posing a further threat to certain native species.

Purple fountain grass is very common in Gran Canaria, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chloris barbata Peacock-plume grass

The origin of this plant, also known by the names purple top and swollen fingergrass, is uncertain. Some authorities maintain that it is native to Tropical America, others claim that it is indigenous in Tropical Africa.

Whatever its origin may be, it has been accidentally introduced to most warmer parts of the world and is regarded as an invasive in a number of countries, including Australia, Korea, Thailand, Cambodia, and India.