Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1997: A thousand eye operations in one day

He now sat down in the shade of a large pipal tree, determined not to move before he had found a satisfactory answer to his quest. For 49 days, he was seated beneath the tree, in deep meditation. Then he arose, convinced that he had found the answer, and that he was able to recognize the coherence of life.

From this day, he walked about, giving lectures to people about his new philosophy. His followers called him The Buddha (‘The Enlightened One’), and the place he had been meditating was named Bodhgaya. Today, it is a major Buddhist pilgrimage goal. A large number of temples have been erected here, and an offspring of the original pipal tree has been preserved. (The life of The Buddha is related on the page Religion: Buddhism, whereas the pipal tree is presented in depth on the page Plants: Pipal and banyan – two sacred fig trees.)

This ashram was established in 1954 by Dwarko Sundrani, who is now 76 years old. He was given a piece of land in Bodhgaya by philosopher and advocate for human rights Vinayak Narahari Bhave (1895-1982), often labelled Acharya (Sanskrit for ‘teacher’), who was a disciple of the freedom fighter Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948), often called Mahatma (Sanskrit for ‘venerable’ or ‘one with a great soul’). Samanwaya means ‘harmony’, whereas ashram means ‘fellowship’.

The main goal of the ashram is to make people more harmonious, peaceful and socially conscious through education, meditation, and social work. Residents and guests are required to comply with Gandhi’s 11 principles: speak truthfully, being non-violent, not stealing, live in celibacy, work physically, not amass wealth, not succumb to pleasures, be fearless, be self-sufficient, have equal respect for all religions, and, finally, work actively to remove the Indian caste system. (This system is described in depth on the page Religion: Hinduism.)

The ashram is situated at the outskirts of town, consisting of a large meeting hall, a library, offices, dormitories, and a large kitchen with a dining hall for 30 persons. Michael introduces me to the leader of the ashram, Dwarko Sundrani.

“We receive much help for our work, from the Indian state as well as private people, also foreigners,” he says. “Volunteers like Michael come here to work for up to four months, receiving only lodging and boarding.”

In 1968, the management of the ashram decided to include schools in the education. The first one was built on 31 ha of donated land, and a kitchen, a dormitory, a stable, and a dairy were also constructed, besides two water reservoirs. Jungle was cleared to be able to start cultivation. Today, this place is flourishing with fertile fields, 50 milking cows, and no less than about 100 children and 11 teachers in the school.

The children are not only taught reading, writing, mathematics, and natural science, but also hygiene, a feeling of community, and religious tolerance, and practical issues like crafts, cultivation, cattle farming, and digging wells. English is not taught, as the goal for the children is that they should return to their village. When poor Indian children are taught English, they often leave their village, believing, erroneously, that English is the key to work and wealth in the large cities.

The creative mind of the children is accomodated through song, dance, drawing etc. A new initiative is Vriksa Sansar (‘tree world’), in which the children learn to plant bamboo, mango, teak, and other trees to provide the village with timber, firewood, food, and cattle fodder. Surplus production can be sold.

Today, Samanwaya Ashram manage no less than 350 education centres in 160 villages. The teachers are mostly locals who have been educated in the ashram, after which they return to teach their own people. About 10,000 poor children have received practical education, enabling them to have a better chance to get work – often with excellent results.

A few children, mostly orphans and outcasts, are educated at the ashram itself. It is the duty of Michael and the three other Danish volunteers to take care of these children. They have come to Bodhgaya through the Danish society Venner af Samanwaya Ashram (‘Friends of Samanwaya Ashram’), established in 1992.

Poor hygiene, combined with the intense sunshine, result in the fact that at least 2 million people in Bihar suffer from cataract. The Bhansali Trust has been founded by an enormously wealthy diamond family in Gujarat, western India, and a part of this wealth is donated every year to carry out eye operations in Bihar. Over the last 13 years, more than 111,000 people have been operated for cataract in Bodhgaya, taking place in the world’s largest eye camp.

Patients and their relatives are also fed in the camp – as opposed to the Indian hospitals, where patients or their relatives must bring food and cook it themselves. Three times a day, huge amounts of rice, vegetables, and dahl (lentils) are cooked in enormous cauldrons, sometimes for up to 7,000 persons at a time. Then patients and their relatives line up, each carrying a plate. Spoon or fork is not necessary, as most Indians eat with their right hand. Everything takes place peacefully and quietly, without commotion, which is rather surprising in India.

In a tent in front of the sheds, the patients are waiting, sitting in long rows. The vast majority are old people, wrinkled and furrowed after toiling in the field throughout their life. A few are younger people and children.

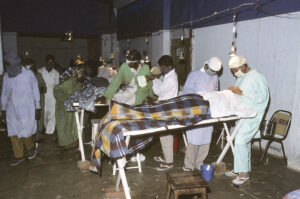

Only one eye on each patient is operated at a time, and prior to the operation it is anesthetized. The patient lies down on a bed with wheels, and a long syringe containing anaesthesia is injected behind the eyeball. It looks rather fearsome, but not a sound is uttered by the patient, who has to rest a bit until the anaesthesia takes effect. Then he or she is wheeled into the adjacent shed.

Here, 44 beds are lined up, close together, and at every second of them an eye surgeon and his assistant are standing, operating under primitive conditions. However, everything is nice and clean. “Our infection percentage is only around 2,” says one of the surgeouns, as his experienced hand cuts into the eye, removing the hazy lens with a tweezer. Then he quickly sows the wound, placing a bandage on the eye. Meanwhile, another patient is ready on the next bed.

One of the assistants stands out from the crowd with her blond hair, Swedish nurse Karin Malmberg, who lives in Denmark. This is the second time she participates in an eye camp.

“It’s fantastic to be here,” she says, “the working moral is very high, and the atmosphere is fine, albeit a little hectic. There is time to fool around a bit, despite operations taking place from 7 in the morning to 12.30, and again from 13.30, until the insects start swarming around the lamps in the evening.”

Often, more than a thousand people are operated in one day. A few days later, when the camp is over, the number for 1997 is calculated at 13,400, operated in 18 days.

The day after the operation, several hundred patients are lying side by side on a long concrete couch, waiting to be examined. If the operation has been successful, they are given a pair of strong eye glasses instead of artificial lenses, which are expensive and require a more complicated operation. Only children and younger people receive such lenses.

Four days later, patients and relatives are driven back to their village, and a control visit is made a couple of weeks later, to make sure that the wound is not infected.

We follow a bumpy gravel road, full of holes, and after some time it is blocked by large piles of stones, to be used to improve the road. We shall have to walk the remaining 5 km. On our way, we encounter several Bhogta people, carrying large bundles of firewood on the head. They often spend an entire day collecting a single bundle, after which they face half a day’s walk to the nearest town, where they sell them for the meagre price of about 50 pence per bundle.

“They have not completely abandoned their habit of making a living from hunting and selling firewood,” says Dwarko. “I would prefer that they concentrate on growing vegetables and fruit, which gives more money, but you cannot expect to change people’s lives from one day to the next.”

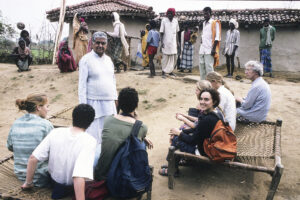

We walk across the fields to a small village with brown wattle-and-daub houses, the majority thatched with grass, but a few with tiled roof. We are received by the village elders, and two beds are hauled out for us to sit on. Dwarko relates how the Bhogta were formerly living.

“They were nomads, roaming the low mountains you see behind the village. They made a living hunting wild animals like deer, wildboar, and bears, and the women collected edible leaves and roots. Just 30 years ago, there was enough space and wildlife, but up to now the population of India has more than doubled, growing from 450 million to 950 million. The space dwindled, and the competition securing wildlife increased. Finally, there was not enough space or wildlife for the Bhogta to continue their way of living. They constructed primitive houses here, but were living in poverty, as they had no knowledge of cultivation. We have helped them to start growing crops and to improve their houses, and we have constructed a well, so that they have access to clean drinking water.”

The well-tended fields around the village bear testimony to his words. A small school has also been erected, and we pay a visit to it. In the class room, about twenty small children are sitting on the floor with tablet and chalk. One of them bursts out crying on seeing the unfamiliar strangers, and the teacher must console. She herself is a Bhogta, who received her education at Samanwaya Ashram.

In a country about to suffocate in population growth, corruption, and egoism, it is indeed a relief to encounter a person like Dwarko Sundari, who has dedicated his life to give some of the poor, landless, and suppressed people of Bihar a dignified life.