Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Himalayan flora 3

On this page, Tibet (in Chinese Xizang), Qinghai, and Xinjiang are treated as separate areas. The term ‘western China’ indicates Chinese territories just east of Tibet and Qinghai. The term ‘south-western China’ encompasses the provinces Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan.

I would be grateful to receive information on any errors on this page, or if you are able to identify any of the species left unidentified. You may use this address: respectnature108@gmail.com.

The flower structure of these plants is unique, with 5 coloured sepals, the upper ones forming an erect hood, and 2-10 inner petals, 2 of which have nectar-producing spurs hidden under the hood. The fruit is a follicle, which is pod-like, but at maturity splitting along one side only.

The major part of the species are deadly poisonous, even in small dosages. In the old days, the poisonous juice of aconite species was applied to hunting arrows all over Eurasia, and it was also applied to arrows and spears during wars. In some areas, it was utilized to eliminate criminals.

The generic name refers to the mythical mountain Akonitos, near the Black Sea, where the Greek hero Heracles (in Latin known as Hercules) went to the underworld Hades to bring up its guardian, the three-headed dog Kerberos. As he tugged this terrible animal out of Hades, its froth fell on the ground as drops, from which aconite sprouted – a figure of the extreme toxicity of the genus.

The common names monkshood and helmet flower refer to the flower structure (see above), whereas the name wolfsbane refers to lycoctonine (derived from Ancient Greek lykos, ‘wolf’), an alkaloid found in these plants, which was formerly utilized to kill wolves, either by shooting them with arrows smeared in aconite juice, or by placing stakes, smeared in the juice, in trenches, in which a bait had been placed.

The role of these plants in traditional medicine and folklore is related on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

It is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to Bhutan, growing in shrubberies and on open slopes at elevations between 2,100 and 3,800 m.

One of the most poisonous plants in the world. Nevertheless, it is widely used in traditional medicine. In Nepal, a paste of the root is applied to treat neuralgia, leprosy, cholera, and rheumatism. It is also considered diuretic and diaphoretic. The leaves are burned as incense. Hunters smear arrows in juice to kill prey. Formerly, shamans used this plant to create visions.

It is threatened by excessive collecting.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wild’ or ‘fierce’, presumably alluding to its toxicity.

It is easily identified by the pale flowers and the leaves, which are divided into very narrow segments. Stem to 1 m tall, branched. Leaves few, lower stalked, to 10 cm across, rounded in outline, deeply divided 3 times into narrow segments, ultimate segments narrowly triangular to linear, to 2 mm broad. Flowers variable, to 3 cm long, in a spike-like, few-flowered, terminal cluster, to 9 cm long, corolla bluish, greenish-yellow, white with purplish tinge, or white with a purple hood. The hood is rather open. Flowering occurs August-October.

In Nepal, juice of the root is used for stomach ache.

The specific name commemorates Scottish gardener and botanist James Alexander Gammie (1839-1924), who collected plants for the Calcutta Herbarium. He also studied mammals, birds, and reptiles.

The flower colour in this genus is very variable, scarlet, orange, yellow, white, or blue. The fruit is a cluster of achenes.

The generic name refers to the Greek god Adonis, who died of his wounds while hunting wild boar, and was transformed into a blood-red flower, stained by his blood. Some species in this genus have scarlet flowers. See also Anemone below.

The common name also alludes to the members with scarlet flowers, which have a dark centre.

It has a rather limited distribution, found from central Nepal eastwards to Sikkim, growing on open slopes at elevations between 3,600 and 4,500 m.

These plants have no sepals – or maybe the sepals are coloured, and the petals missing. On this page, I call them petals. The fruit is a cluster of tiny, nut-like achenes, in some species hidden among woolly hairs.

The name anemone is often linked to the Ancient Greek word anemos (’wind’), and windflower is a common English name of these plants. The connection, however, is hard to see, and, as indicated below, it is probably a wrong assumption.

According to Philip K. Hitti, in his book History of Syria including Lebanon and Palestine (1951), the Arabic name of the crown anemone (A. coronaria) is shaqa’iq an-Nu’man, which literally translates as ‘the wounds, or pieces, of Nu’man’. Nu’man probably refers to the Sumerian god of food and vegetation, Tammuz, whose Phoenician name was Nea’man. It is generally believed that the Arabic an-Nu’man became anemos in Ancient Greek, and that Tammuz was adopted by the Greeks as Adonis, who died of his wounds while hunting wild boar, and was transformed into a blood-red flower, stained by his blood. In the Near East, the crown anemone is often of the blood-red variety.

Lately, many species of this genus have been transferred to the genera Eriocapitella, Anemonoides, and Anemonastrum by Kew Gardens, based on small differences. This is a bit of a mystery to me, and, for the time being, I retain the old systematics.

A number of anemone species from other parts of the world are described on the page Plants: Anemones and pasque flowers.

It is very variable, more or less hairy on all parts, except flowers. Leaves numerous, stalked, blade 3-partite, ovate or rhombic in outline, to 8 cm long and broad, hairy, base heart-shaped, segments again 3-partite.

Flower-stalks may grow to 50 cm tall, but are usually much lower, inflorescence a terminal umbel with up to 8 flowers, involucral bracts 3-partite or 3-lobed, to 4 cm long. Individual flowers stalked, petals 5-7, white, blue, purple, or red, to 1.8 cm long and 1.2 cm wide. They appear May-July.

The specific name is Latin, in a botanical context with two meanings, ‘pendent’ or ‘low’. What it refers to in this case is not clear.

Leaves are numerous, basal, soft-haired, rounded in outline, blade to 8 cm across, 3-lobed, rather rounded-toothed. Flower-stalk to 15 cm long, flowers numerous, in spreading umbels, involucral bracts stalkless, very variable in shape, 3-lobed or undivided, to 3 cm across, corolla to 5 cm across, but usually smaller, petals 5-8, elliptic to obovate, soft-haired beneath, colour variable, white, blue, or bright yellow, the latter restricted to Kashmir and northern Pakistan. It has a long flowering period, from May to September.

In Nepal, juice of the root is used for eye trouble.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with rounded lobes’, alluding to the leaves.

It is distributed from Pakistan eastwards to Bhutan, found in forests and shrubberies, and on open slopes, at elevations between 2,400 and 4,300 m.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek polys (‘many’) and antheros (‘anther’).

Often a large plant, stem to 1 m long, leaves 3-5, long-stalked, soft-haired, rounded in outline, blade to 15 cm across, lobes 3, toothed or cut. Flowers to 3 cm across, many in a terminal long-stalked umbel, involucral bracts 3-4, like the leaves, but stalkless, blade 3-lobed, lobes narrower than on the leaves. Petals 5-10, white above, purplish-violet beneath, elliptic to obovate, soft-haired beneath. Flowering occurs May-August.

In Nepal, the seeds are roasted and pickled. Medicinally, a paste of the plant is used for cough and fever, a decoction of the root is applied to wounds, and juice from the leaves is mixed with water and inhaled to relieve sinusitis.

Some authorities place this species in the genus Eriocapitella.

The specific name is derived from the Latin rivus (‘small stream’), thus ‘growing along streams’.

It is found in Central Asia, from Uttarakhand eastwards across the Himalaya to northern Myanmar and south-western China, growing in forests and shrubberies, and on open slopes, at elevations between 2,500 and 5,000 m.

Some authorities place this species in the genus Anemonastrum.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing on rocks’ – not a suitable name, as it is mainly found on open slopes or among shrubs.

Basal leaves 3-7, sparsely hairy, leathery, blade heart- or kidney-shaped, to 20 cm across, lobes 5, deeply cut, toothed, leaf-stalk to 40 cm long. Flower-stalk to 75 cm tall, hairy, involucral bracts 2-5, stalkless, blade 3-lobed, lobes narrow, toothed, downy, flowers white, to 3 cm across, 7-15 in a terminal umbel, petals 4-7, obovate to oblong. The flowering period is from June to August.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘with 4 sepals’ (on this page called petals). However, it may have up to 7.

It is found from Afghanistan eastwards across the Himalaya and southern Tibet to south-western China, and also in Taiwan, growing in open forests and grasslands, and along streams. In the Himalaya, it may be encountered at elevations between 2,000 and 3,300 m.

In Nepal, it is used medicinally for various ailments, including toothache, headache, and dysentery. A paste of the root is applied to treat scabies, and juice of the root is used to expel intestinal worms. The toxic leaves are strewn in rivers to stupefy fish, and powdered leaves are applied to the head to kill lice. The woolly seed hairs were formerly used as tinder.

The specific and popular names were given in allusion to the upper stem leaves, which resemble those of the grape vine (Vitis vinifera).

Some authorities place this species in the genus Eriocapitella.

They are characterized by the peculiar shape of the flowers, each of the 5 petals having a spur, pointing backwards, and curved in many species. The petals alternate with 5 narrower and smaller sepals, usually of the same colour as the petals. The leaves are tripartite, with blunt lobes. The upper stem leaves are small, bract-like.

The generic name was first used by Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin (see below), when he described the Alpine columbine (A. alpina, presented on the page Plants: Flora in the Alps and the Pyrenees). The name is derived from the Latin aqua (‘water’) and legere (‘to collect’), thus ‘water jar’, referring to the shape of the flower.

Another interpretation claims that it is derived from the Latin aquila (‘eagle’), where the spurs are likened to eagle claws.

The common name columbine is derived from the Latin columba (‘dove’), referring to the alleged resemblance of the inverted flower to five doves, clustered together. Another popular name is granny’s bonnet, again referring to the flower shape.

In his outstanding work Pinax theatri botanici (‘Illustrated exposition of plants’), from 1623, this brilliant scientist described about 6,000 plant species, classifying them in a form, which almost equals the binominal nomenclature, introduced by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in 1753.

The major part of the information above is from the website en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaspard_Bauhin.

Stem to 80 cm tall, branched above. Basal leaves twice divided into 3 parts, each leaflet with 3 toothed lobes, to 4 cm long, leaves getting gradually smaller up the stem, the uppermost bract-like with 1-3 lanceolate, pointed segments. Flowers several on each branch, horizontal or slightly nodding, to 5 cm across, white or cream-coloured, fragrant, spurs straight or hooked, to 1.8 cm long, sepals to 3 cm long and 1.2 cm wide, blunt or pointed. It flowers June-August. Follicles 6-9, densely hairy.

Flowers are mostly nodding, to 3.5 cm across, 2 or more on each branch, sepals ovate, to 2.1 cm long, bluish, purplish, or white with a purplish tinge, petals yellowish or white with a bluish tinge, erect, to 1.3 cm long, spur straight or slightly curved, to 2 cm long. Blooming period is June-August. Follicles 5-6, hairy, to 2.5 cm long.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to south-western Tibet and western Nepal, growing on open slopes and in shrubberies near streams, found at altitudes between 2,700 and 4,200 m. It is common in Ladakh.

The specific name was given in honour of British veterinary surgeon and botanist William Moorcroft (1765-1825), who explored several areas in the Himalaya and Central Asia. He was the first European to make botanical collections in western Tibet and Kashmir.

It occurs from Pakistan eastwards to western Nepal, growing at elevations between 2,400 and 3,300 m. Habitats include forests, shrubberies, and grasslands.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with downy flowers’.

Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) states that “Caltha is a plant with yellow flowers.” The word is possibly derived from Ancient Greek kalthe (‘of yellow colour’).

Inflorescences are terminal, branched, with up to 8 flowers, to 3 cm across, petals 5, broadly ovate, deep yellow, with numerous yellow stamens. Self-pollination occurs in rainy weather, as the flowers fill with water, and anthers and stigma are at the same height. The plant may also spread by rooting at the nodes.

At lower elevations, flowers may appear as early as March, but blooming may also take place late in the summer, in August, especially at higher altitudes.

As its name implies, this is a plant of marshy areas, in meadows, ditches, wet forests, and along streams. Its distribution is circumpolar in subarctic and temperate areas, southwards to Oregon, South Carolina, the Mediterranean, Iran, and northern Indochina. It is found throughout the Himalaya, at elevations between 2,400 and 4,200 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin palus (‘swamp’), alluding to its preferred habitat.

It is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to south-western China, and thence northwards to Gansu and Qinghai, growing in marshy meadows and along streams, at altitudes between 2,800 and 4,100 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with leafless flower-stalks’.

These plants are climbing due to the sensitivity of the leafstalks which, when touching another plant or something else, start twisting, curling around the object.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek klema (‘climber’).

Inflorescences are axillary, branched clusters, bracts narrowly ovate to lanceolate, to 4 cm long, flowers to 2 cm long and across, white or yellowish, petals recurved. Flowering takes place August-October, ripening of fruits September-November.

It is found from Pakistan eastwards to south-western China, growing at altitudes between 1,800 and 3,400 m. Habitats include forests, shrubberies, and along streams.

In Nepal, juice of the plant is inhaled to treat sinusitis.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘born at the same time’, but in a botanical context it refers to two connected items, in this case the leaf-stalks.

A woody climber, to 10 m long, branches with up to 10 shallow grooves, leaves trifoliate, long-stalked, in axillary clusters, stalk to 9 cm long, blade of leaflet ovate or elliptic, to 10 cm long and 5 cm broad, margin toothed, tip pointed.

Flowers are stalked, to 6 cm across, up to 6 together in axillary clusters, petals 4, white, sometimes pinkish, spreading, obovate or oblong, to 6.5 cm long and 3.5 cm wide, tip usually blunt. Stamens numerous, filaments white, to 5 mm long, anthers violet. It blooms between April and June, and ripening of fruits takes place June-September.

Flowers axillary, to 4.5 cm across, up to 3 together, stalk to 13 cm long, petals 4, yellow with brown dots, sometimes purplish-brown, orange, or yellowish-green, to 2.8 cm long and 1.7 cm wide, ovate or oblong, pendent or spreading, woolly-hairy above and on margin, tip pointed. It flowers May-August, and ripening of fruits takes place July-October.

This plant is distributed from Xinjiang southwards across Tibet to Pakistan and Ladakh, and thence eastwards to Nepal, growing in dry open areas, especially on stone walls along fields, at altitudes between 1,700 and 4,000 m. It is very common in Ladakh.

Flowers are irregular, with 5 sepals, the upper one with a large, back-pointing spur, and 4 inner petals, of which the upper 2 have nectar-producing spurs that are enclosed in the larger spur.

Despite being extremely poisonous, these plants were previously much used in folk medicine as a sedative, and to treat various ailments, including fluid retention, poor appetite, and insomnia, and to get rid of intestinal worms. Some members were formerly included in the genus Consolida, the name derived from the fact that these plants were used in the Middle Ages to help consolidate (i.e. coagulate) blood. They are deadly if consumed by livestock.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek delphinion (‘dolphin’). In his De Materia Medica, Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.) says that the these plants are named for their dolphin-shaped flowers. The English names refer to the long spur.

It grows on stony slopes in dry areas, at altitudes between 3,500 and 5,500 m, distributed from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Ladakh, and Himachal Pradesh eastwards across southern Tibet to eastern Nepal. It is quite common in Ladakh and Lahaul.

In Ladakh, juice of the plant is used for treating colic, flowers and leaves for fever, bile, food poisoning, skin disease, and to expel intestinal worms. In Nepal, juice of the plant is used to kill ticks on domestic animals.

The specific name probably commemorates Scottish botanist Robert Brown (see below).

By 1800, Brown was one of the foremost botanists in Ireland, corresponding with a number of established botanists. In 1801, he became a member of an expedition to Madeira, South Africa, and Australia, on board the Investigator, whose captain was British navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders (1774-1814). For three and a half years, Brown studied Australian plants, collecting about 3,400 species, of which about 2,000 were previously unknown to science.

In 1810, he published his results from the expedition in Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen (‘Preliminary Flora of New Holland [today Australia] and van Diemens Island’ [today Tasmania]), the first systematic account of the Australian flora.

The same year, he was appointed librarian of the famous botanist Joseph Banks (1743-1820), and when Banks died in 1820, Brown inherited his library and herbarium, which were transferred to the British Museum in 1827.

In 1830, Brown was one of the founding members of the Royal Geographical Society, and he served as president of the Linnean Society 1849-1853.

Inflorescences are widely branched, few-flowered, terminal clusters, bracts to 1.5 cm long, linear, flowers to 2.5 cm long, including the straight spur to 1.5 cm long, corolla blue or violet, spur white. Flowering takes place May-August.

A rather common plant, found from Pakistan eastwards to central Nepal, growing at elevations between 1,500 and 2,700 m. Habitats include open forests, grassy areas, and along fields and trails.

In Nepal, a paste of the root is applied to treat toothache.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘naked’, presumably alluding to the stem, which is usually smooth.

It is hairy all over, stem usually below 15 cm long, at lower elevations up to 30 cm. Leaf-blade to 4 cm across, 3-lobed, each lobe cut into many narrow, toothed segments. Inflorescences are branched, few-flowered, terminal clusters, bracts leaf-like, bracteoles entire, lanceolate or linear, to 1.2 cm long, flowers short-stalked, pale-blue or mauve, to 4 cm long, including the straight, conical spur, to 1.4 cm long, thick at the base. Flowering occurs July-September.

The specific name is derived from the Latin glacies (‘ice’), referring to the plant growing at very high elevations.

This plant is endemic to western and central Nepal, growing in open areas at elevations between 2,000 and 4,500 m.

In Nepal, juice of the root is given for cough and colds. An infusion of the root is applied to wounds in the hooves of cattle to expel maggots or kill germs.

It is distributed from Uttarakhand eastwards to central Nepal, across southern Tibet to the Yunnan Province, and thence nortwards to Gansu and Qinghai, in the Himalaya growing in grasslands and on open slopes at elevations between 3,000 and 4,300 m.

In Nepal, a decoction of the plant is applied to treat scabies.

The specific name refers to the district of Kumaon, in present-day Uttarakhand, which was formerly a kingdom, known as Kemaon or Kamaon. Presumably, the type specimen was collected in this area.

These plants were previously included in Ranunculus (below), but they are possibly more closely related to Oxygraphis (below), or to the American genus Cyrtorhyncha.

The stem is to 35 cm long, smooth, branched, rooting at the nodes. Leaves variable, 3-5-lobed or rarely entire, blade to 2.6 cm long and 2.2 cm across, smooth, lobes often rhombic, blunt. Flowers are solitary, short-stalked, to 1.2 cm across, sepals 4-5, ovate or elliptic, to 5 mm long, petals 5, bright yellow. Blooming occurs June-August.

In Ladakh, leaves, stem, flowers, and fruit are used for heat disorders of tendons and ligaments.

The specific name is derived from the Latin tria (‘three’) and cuspis (‘point of a spear’), alluding to the leaves often being tripartite, with pointed segments.

It grows on open slopes, often where the snow has recently melted, at elevations between 2,200 and 5,000 m, distributed from Pakistan eastwards to Bhutan.

The specific name commemorates Austrian botanist and sinologist Stephan Ladislaus Endlicher, born István László Endlicher (1804-1849), director of the Botanical Garden in Vienna. In his work Genera Plantarum (1831-41), he produced a new system of plant classification.

The generic name is a diminutive of rana (’frog’), thus ’little frog’, referring to the fact that many buttercup species grow in wet areas, where frogs live. The English name refers to the butter-yellow flowers of many species, and the tiny ‘cup’, formed by the petals. The name crowfoot was given in allusion to the tripartite leaves of some species, which somewhat resemble a bird’s foot, whereas spearwort alludes to species with long, undivided leaves.

When left unharmed, many buttercup species may cover huge areas. Grazing animals avoid them, as they contain the toxic anemonol. However, when dried as hay, the toxicity disappears.

According to an old belief, cows grazing on buttercups would produce the sweetest and most flavourful milk, rich in cream. Of course, this is pure superstition, as cows avoid these plants due to their toxicity. Rather, the richness of the milk would stem from the succulent grass in the meadows.

Stem to 12 cm long, erect or ascending, sometimes branched, basal leaves many, stalked, rounded in outline, divided into narrow lobes, stem leaves dissected into linear, pointed segments, to 1.5 cm long, upper ones stalkless. Flowers solitary, terminal, to 1.3 cm across, sepals 5, hairy, ovate, reflexed, to 3.2 mm long, petals 5, obovate or elliptic, bright yellow, to 8 mm long and 4 mm wide. Blooming takes place between May and August.

The specific name was given in honour of Finnish botanist Viktor Ferdinand Brotherus (1849-1929), an expert of mosses.

Flowers solitary, axillary, long-stalked, to 1.5 cm across, sepals ovate, to 6 mm long, hairy, petals 5-6, obovate, to 7 mm long and 4 mm wide, bright yellow. Flowering takes place March-July.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China, growing at altitudes between 1,000 and 4,000 m. Habitats include grasslands, shrubberies, among rocks, and along streams.

In Nepal, young shoots are dried and cooked as a vegetable, and also fermented to make gundruk (see Arisaema utile, Himalayan flora 1). The pounded root is applied to wounds. Juice of the root is used for stomach ache.

What the specific name refers to is not clear.

Stem usually below 10 cm tall, occasionally to 20 cm, creeping, ascending, or erect, smooth, often branched. Leaves very variable, to 1.6 cm long and 9 mm wide, linear, elliptic, or ovate, usually entire, sometimes lobed or toothed. Flowers solitary, terminal, short- or long-stalked, to 1 cm across, sepals 5, elliptic or ovate, to 7 mm long and 5 mm broad, hairy, sometimes black-tipped, petals 5, bright yellow. Flowering period June-August.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘pretty’ or ‘beautiful’.

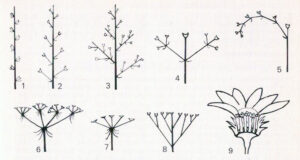

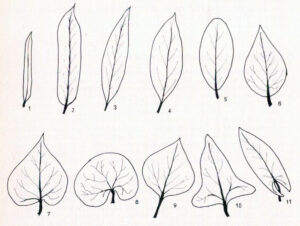

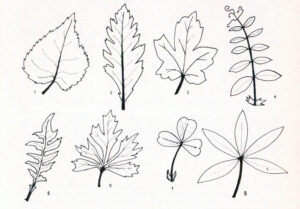

The leaves of these plants are large and divided two or three times, and the flowers are arranged in many-branched clusters, in which the numerous, often brightly coloured stamens have taken over the role as display apparatus instead of the petals, which are often small or absent. However, 3 species below, T. chelidonii, T. reniforme, and T. virgatum, have conspicuous petals.

The generic name is a Latinized form of the Ancient Greek name of these plants, thaliktron. The popular name stems from the similarity of the leaves to those of the genuine rues (Ruta).

It grows in forests and shrubberies at elevations between 2,600 and 4,300 m, distributed from Kashmir eastwards to south-eastern Tibet and northern Myanmar.

The specific name is Greek, meaning ‘swallow-like’. What it refers to is not clear, perhaps the shape of the flower.

Inflorescences are terminal or axillary, many-flowered clusters, petals small, green or yellowish-green, to 4 mm long and 1.5 mm wide, stamens many, to 1 cm long, filaments purple, anthers purplish-yellow. The flowering period is long, from May to September.

It is widespread, found from southern Europe eastwards to south-eastern Siberia, southwards to Turkey, Iran, the Himalaya, and central China. In the Himalaya, it is restricted to the western part, from Pakistan eastwards to central Nepal, growing in forests, grasslands, and rocky areas at elevations between 1,500 and 4,700 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘stinking’.

A tall plant, stem to 2.6 m long, branched, leafy, leaves to 45 cm long, divided 3-4 times, leaflets rounded, to 1.5 cm across, with 3-7 blunt teeth. The inflorescences are terminal or axillary, many-flowered panicles, to 20 cm long, petals 4, white, yellow, purplish, or greenish, narrowly elliptic, to 4.5 mm long and 2 mm wide, soon falling, often giving the impression that the plant has no petals. Stamens longer than petals, filaments thread-like, white or purplish, anthers yellow. Flowering occurs July-September.

Medicinally, this plant is used as a tonic, diuretic, febrifuge, and purgative, and for stomach trouble.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with many leaves’.

Inflorescences to 30 cm long, few-flowered, flower-stalk glandular-hairy, flowers large, to 3.5 cm across, petals 4, reddish-pink or mauve, anthers yellow. Flowering takes place July-October.

It is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to Bhutan and south-eastern Tibet, growing in forests and shrubberies at elevations between 2,800 and 3,700 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shaped like a kidney’. This term is usually applied to plants, whose leaves are rounded, broader than long.

Stem to 65 cm long, branched or unbranched. Leaves simple, 3 together, broadly triangular, to 2.5 cm across, 3-lobed, lobes with rounded teeth. Flowers to 2 cm across, in terminal or axillary, few-flowered clusters, petals 4 or 5, white or pinkish, to 8 mm long and 4 mm broad, stamens only a little longer, white. It blooms June-August.

The specific name is derived from the Latin virga (‘staff’), alluding to the numerous straight stems.

Many members of this family have a hypanthium, in which the basal portions of calyx, corolla, and stamens form a cup-shaped tube, also called floral cup.

Amygdaleae, genus Prunus (trees or shrubs, fruit a drupe).

Exocordeae, genus Prinsepia (shrubs, fruit a drupe).

Maleae, genera Cotoneaster, Pyracantha, Pyrus, and Sorbus (trees or shrubs, fruit a pome).

Neillieae, genus Neillia (shrubs, fruit hairy carpels, encircled by the persistent calyx).

Sorbarieae, genus Sorbaria (shrubs, fruit achenes or aggregated follicles).

Spiraeeae, genus Spiraea (shrubs, fruit a follicle).

About 40 species occur the Himalaya, of which up to 12 are evergreen, creeping, and mat-forming, all very similar and difficult to distinguish. The plants called C. microphyllus below are only tentatively identified to this species.

Most species have white flowers, some pink or red. The fruit is a pome, berry-like, with a swollen receptacle, enclosing 2-5 carpels.

The generic name is derived from the Latin cotonium, a corruption of cydonium malum, which means ‘the apple (or quince) from Kydonia’ (a town in Ancient Greece, situated on the northern coast of Crete, near present-day Chania), combined with the suffix aster (‘resembling’), thus ‘the fruit which resembles cotonium’.

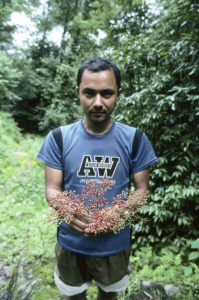

Inflorescences are dense clusters with up to 40 flowers, stalk densely hairy. Flowers to 7 mm across, hypanthium bell-shaped, woolly-hairy, sepals tiny, triangular, petals white, spreading, ovate or rounded, to 3.5 mm long, stamens slightly shorter than petals. Flowering takes place May-July. The fruit is scarlet, ellipsoid, to 5 mm long, ripening September-November.

It is distributed from Uttarakhand eastwards to Bhutan and south-eastern Tibet, found in open forests and shrubberies, and along streams, at elevations between 2,200 and 3,400 m. It is very common in Upper Langtang Valley, central Nepal.

In Nepal, the fruit is eaten to treat blood deficiency.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing in cold places’.

Flowers are axillary, solitary or 2-3 together, to 1 cm across, pinkish in bud, later white, hypanthium bell-shaped, hairy, sepals ovate-triangular, tiny, pointed, petals 5, spreading, rounded, to 4 mm across, stamens 15-20, shorter than petals. Flowering occurs April-June. The fruit is scarlet, globular, to 1 cm across, ripening July-October.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China, growing on rocks and in open areas at altitudes between 2,000 and 5,400 m.

In Nepal, it is planted to prevent soil erosion. Branches are used for fences, as fuel, and for basket-making. The leaves are burned as incense. Ripe fruits are edible, but tasteless.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek mikros (‘small’) and phyllon (‘leaf’).

The plants in the pictures below are only tentatively identified to this species.

It grows on rocky slopes at elevations between 1,800 and 3,100 m, found from Afghanistan eastwards to Uttarakhand.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rose-coloured’, referring to the flowers.

The generic name commemorates Scottish printer and naturalist Patrick Neill (1776-1851), founding member of the Wernerian Natural History Society and the Caledonian Horticultural Society. His work A Tour Through Some of the Islands of Orkney and Shetland (1806) caused much public debate due to its descriptions of the economic misery of the islanders.

A shrub to 2 m tall, branches slender, often pendent, reddish-purple, angular, hairy when young. Leaves to 10 cm long and 5 cm wide, blade broadly ovate to almost triangular, 3-lobed, base heart-shaped, smooth on both surfaces, margin coarsely toothed, tip long-pointed, nerves impressed on the upper surface.

Inflorescences are axillary or terminal clusters, to 5 cm long, with up to 12 short-stalked flowers, to 8 mm across, hypanthium cup-shaped, sepals triangular, hairy, petals reddish, pink, pinkish-white, or greenish-white, obovate, to 3 mm long. Flowering occurs June-August.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with red flowers’.

The fruit is a drupe, with a fleshy outer layer and an inner hard stone, enclosing the seed.

The generic name commemorates English scholar and orientalist James Prinsep (1799-1840), best remembered for deciphering the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts of ancient India. He also studied many aspects of numismatics, metallurgy, and meteorology, and was the founding editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Inflorescences are short racemes, to 6 cm long, in axils of spines, flowers short-stalked, to 1.5 cm across, hypanthium cup-shaped, with 5 unequal lobes, brown-downy, persistent in fruit. Petals white, rounded. They appear in the winter period, from October to May. The fruit is blue to blackish-purple, oblong-cylindric, to 1.7 cm long, ripening April-September.

It occurs from Pakistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China, growing in shrubberies and villages, on open slopes, and along trails, at elevations between 1,200 and 2,900 m.

In Nepal, oil from the seeds is applied for rheumatism and muscular pain, and to the forehead to relieve cough and colds. Heated oil cake is applied to the abdomen in case of stomach ache, and the oil cake is also used for washing clothes. The oil can be burned in lamps. This species is planted to prevent soil erosion, and to make fences. Goats browse on the leaves. A purple colour is obtained from the fruits, which is used for painting. Ripe fruits are edible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of much usage’. A suitable name!

The fruit is a drupe, with a fleshy outer layer and an inner hard stone, enclosing the seed.

The generic name is a Latinized version of the Ancient Greek name of the plum tree, prounos.

Flowers are long-stalked, solitary or up to 4, terminal, appearing when the tree is without leaves, or with the young leaves. Sepals usually reddish, triangular, pointed, petals pink or whitish, ovate or obovate, spreading, to 1.5 cm long. It is flowering from September and through the winter. The drupe is yellow, red, or purplish-black, ovoid, smooth, to 1.6 cm long and 1.2 cm broad, ripening between March and May.

It is distributed from Pakistan eastwards along the Himalaya to northern Indochina, growing in forests and open areas at altitudes between 1,200 and 2,400 m.

This tree is often planted at villages, cultivated for the edible fruits, and as an ornamental. Fruits and leaves yield a dark green dye. The wood is hard and durable. In Nepal, the foliage is lopped for fodder. Walking sticks are made from the branches, necklaces and rosaries from the drupes. Juice of the bark is applied in case of backache.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Cerasus‘, an older generic name of cherry trees.

A medium-sized tree to 18 m tall, with rough grey-brown bark. Leaves oblong or lanceolate, to 15 cm long, margin with numerous fine teeth, tip long-pointed, nerves creating a net-like pattern.

Inflorescences are drooping clusters, to 15 cm long, with numerous flowers, to 1 cm across, calyx with blunt lobes, petals rounded, white. Flowering takes place April-May. The fruit is globular, to 8 mm in diameter, at first red, later dark purple or black, ripening August-October.

In Nepal, the foliage is lopped for fodder. Ripe fruits are eaten and also used to produce an alcoholic beverage.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shaped like a horn’. The fruits of this species are often infected by insects, causing them to grow long and horn-like.

The fruit is a pome, with a swollen receptacle, enclosing 2-5 carpels.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pyr (‘fire’) and akanthos (‘thorn’), alluding to the sharp thorns and the red fruits of these plants. Thus, the English name is a direct translation of the Latin name.

The many-flowered inflorescences are axillary clusters, to 5 cm across, arranged along the branches, flower-stalk to 1 cm long, flowers to 9 mm across, hypanthium bell-shaped, hairless, sepals triangular, tiny, petals rounded, white, to 5 mm across. It flowers between March and May. The fruit is globular, scarlet or orange-red, to 8 mm across, ripening August-November. The nuts are protruding from the persistent calyx.

It is distributed from Kashmir eastwards to northern Myanmar and south-western China, found at elevations between 1,000 and 2,500 m. Habitats include shrubberies, open slopes, and along trails.

In Nepal, it is planted as a hedge, and walking sticks are made from the wood. Ripe fruits are edible. Powdered fruits are used for blood dysentery.

In a botanical context, crenulate means ‘with small, rounded teeth’, derived from the Latin crenula, a diminutive of crena (‘incision’), referring to the leaves.

The fruit is a pome, with a swollen receptacle, enclosing 2-5 carpels.

The generic name is derived from pirus, the classical Latin word for pear.

The branches are often spiny. Leaf-stalk to 3 cm, leaves ovate, sometimes 3-5-lobed, to 10 cm long and 5 cm broad, long-pointed, toothed, downy when young, later hairless, shining.

Inflorescences are umbel-like, with 7-13 flowers, stalk to 3 cm long, flowers to 5 cm across, sepals triangular, to 6 mm long, downy, petals white with darker veins, obovate, to 1 cm long and 6 mm broad. Flowering takes place March-April. The fruit is globular, to 1.5 cm across, at first brownish-green, later brown, with white dots and raised lenticels, flesh with gritty cells. It ripens August-October.

Over-ripe fruits are edible. They are often eaten by birds. In Nepal, the foliage is lopped for fodder, and the wood is used for making walking sticks and small tools, and as fuel. Juice of the fruit is taken for diarrhoea. This juice is also dripped into the eyes of livestock suffering from inflammation of the eyelids.

The specific name is derived from a local Nepalese name for this tree.

These plants resemble the well-known genus Spiraea (below), but the leaves are pinnate. The fruit is dry, with 5 carpels.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Sorbus‘ (whitebeams, below), presumably alluding to the pinnate leaves.

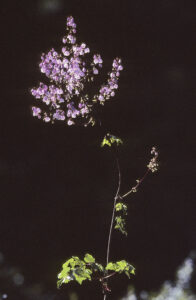

Inflorescences are very large, many-flowered, branched, terminal clusters, to 45 cm long, flowers to 7 mm across, petals rounded, white. They appear between May and August. Carpels 5, hairless, many-seeded.

It is native to western Central Asia, found from Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan southwards to Afghanistan and north-western Himalaya, eastwards to central Nepal. In the Himalaya, it grows in open forests and shrubberies, and along streams and trails, found at elevations between 1,800 and 2,900 m. It is common in the Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh.

In Nepal, juice of the seeds is used to treat liver ailment.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘very hairy’. It is not clear what it refers to.

Leaves are pinnate, lobed, or simple. Flower clusters compound, fruit a pome, with a swollen receptacle, enclosing 2-5 carpels.

The name whitebeam is from Middle English witbeam (‘white tree’), alluding to the colour of the hairs on the underside of the leaves of some species. The alternative name mountain-ash refers to the leaves of some species, whose leaves resemble those of the common ash (Fraxinus excelsior).

The generic name is the classical Latin word for whitebeams, rooted in the Indo-European sor (‘red’), alluding to the fruit colour of most species.

A large deciduous tree, to 25 m tall. Branches purple when young, greyish-brown when older. Leaves simple, short-stalked, stipules brownish, lanceolate, to 1.2 cm long, blade elliptic, to 22 cm long and 12 cm wide, green and shining above, white-woolly below, lateral veins 10-15 pairs, margin unevenly toothed, sometimes lobed, tip pointed.

The inflorescences, each with 30-45 flowers, are up to 10 cm long and across, stalk initially white-woolly, later almost smooth. Flowers to 1.3 cm across, sepals triangular or lanceolate, to 3 mm long and broad, petals white, obovate, to 8 mm long and 6 mm wide. Flowering takes place May-July. The fruit is almost globular, red, to 1.5 cm across, ripening August-September.

Ripe fruits are edible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘pointed’, referring to the leaf shape.

Inflorescences are terminal, lax, few-flowered clusters, to 6 cm long, flowers to 1 cm across, hypanthium purplish-black, broadly bell-shaped, to 3 mm long, hairless, sepals triangular, to 2 mm long, petals rounded, to 4 mm long, pink or white. Blooming time is May-June. The fruit is bluish-white or white, sometimes flushed pink or crimson, globular or ovoid, to 1 cm across, ripening September-October.

It is found at elevations between 3,000 and 4,200 m, from Himachal Pradesh eastwards to northern Myanmar and south-western China. Habitats include forests, shrubberies, and open areas.

In Nepal, the foliage is lopped for fodder.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘small-leaved’, alluding to the pinnately divided leaves.

Twigs are brownish or greyish-brown, leaves pinnately divided, short-stalked, to 18 cm long, stipules broadly ovate or rounded, to 1.2 cm long, cleft or toothed, 9-15 pairs of leaflets, dark green above, paler below, linear or narrowly lanceolate, to 5 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, on the underside with rusty-brown hairs along the midvein, base rounded, margin with short, sharp teeth, tip with a short point.

Inflorescences are terminal, many-flowered, to 10 cm long and across, rachis and flower-stalks densely covered in rusty-brown hairs, flowers to 8 mm in diameter, sepals greenish or reddish, triangular, to 1.5 mm long, smooth, petals rounded, obovate, or rhombic, to 3 mm long and 2 mm broad, white or pale pink. It flowers from May to July. The fruit is globular, pink or red, to 8 mm across, ripening September-October.

In Nepal, a paste of the leaves is applied to boils.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘relating to bears’, presumably referring to the dense layer of reddish-brown hairs on the flower-stalk, which somewhat resembles a bear’s fur.

Leaves are simple. Carpels 5, free or fused at the base. The fruit is a follicle.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek speira (‘spiral’), alluding to the spirally arranged inflorescences of some species (see 3rd picture below).

Inflorescences are domed clusters of white, cream-coloured, or dark pink flowers, to 8 mm across, sepals triangular, petals rounded. Flowering takes place May-July. The ripe carpels are exposed, shining.

It occurs from Himachal Pradesh eastwards to Myanmar and the Yunnan Province, growing in shrubberies and open areas at altitudes between 3,000 and 4,900 m. It is common in upper, drier valleys of Nepal.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘arched’, referring to the arched branches.

It is a deciduous shrub, to 2 m tall, branches erect or ascending, yellow-brown to red-brown, leaves ovate or ovate-lanceolate, to 4 cm long and 2 cm wide, base rounded, margin toothed, tip pointed.

Inflorescences are terminal or axillary, many-flowered, to 4 cm long and across, flowers to 7 mm in diameter, sepals triangular-ovate, to 2.5 mm long and across, petals rounded or oblong, pink, rarely white. Flowering occurs May-July.

In Nepal, the plant is used as fodder for goats and sheep.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘beautiful’.

Inflorescences are long, dense, many-flowered, terminal clusters on short side branches, flowers to 6 mm across, sepals triangular, to 2.5 mm long, petals rounded, to 3.5 mm long, white. Flowering takes place between May and August. Ripe carpels are long-haired, partly enclosed by the calyx-tube.

It is distributed from Pakistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China, growing at elevations between 1,500 and 4,000 m. Habitats include shrubberies, streamsides, and open slopes.

In Nepal, the plant is used as fodder for goats and sheep.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘becoming grey’. What it refers to is not clear.

The generic name stems from Argemone, derived from Ancient Greek argemos, meaning ‘a white spot on the eye’ (cataract), which a species of Argemone (Papaveraceae), according to the Ancient Greeks, was able to cure. Despite their medicinal properties, agrimonies are not known to cure eye diseases, so why the generic name was applied to them is uncertain.

A common name of these plants, church steeples, refers to the long, spire-like inflorescence, whereas cocklebur and sticklewort allude to the prickly fruits, which easily detach when in contact with socks, sweaters, animal furs, etc.

Stem to 1.5 m tall, unbranched, hairy below. Stipules large, sickle-shaped, margin sharply toothed, leaves hairy, gradually smaller up the stem, pinnately divided with 3-4 pairs of very unequal leaflets, larger ones lanceolate or elliptic, toothed, to 5 cm long and 2.5 cm broad, alternating with much smaller ones.

Flowers to 9 mm across, in a terminal, slender, spike-like cluster, calyx tube to 8 mm long, grooved, bristly-hairy, petals yellow. In the Himalaya, flowering occurs May-October. The fruit is very distinctive, top-shaped, 10-ribbed, to 8 mm long and 4 mm broad, with a crown of hooked prickles. It ripens October-December.

In Nepal, this species is used for a large number of ailments, including stomach ache, diarrhoea, dysentery, haemorrhoids, tuberculosis, headache, and peptic ulcer. A decoction of the plant is applied to treat snakebite.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘hairy’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dasys (‘hairy’) and phoros (‘bearing’), alluding to the hairy hypanthium.

A prostrate plant, stem woody, bark reddish-brown, peeling off, branches creeping or ascending, to 15 cm long. Leaves are in fact pinnate, with 5-7 pinnae, but this is hard to see, leaflets crowded, to 6 mm long and 3 mm wide, ovate-elliptic, silky-hairy, tip pointed. Flowers solitary, to 1.7 cm across, petals rounded, yellow, to 8 mm long. They appear June-August.

Plants formerly known as D. fruticosa var. pumila, or Potentilla fruticosa var. pumila, are now included in this species.

The specific name is derived from the genus name Dryas, and Ancient Greek anthos (‘flower’), combined with the suffix oides (‘resembling’), thus ‘resembling flowers of Dryas‘. This genus, likewise in Rosaceae, is presented on the page Plants: Flora of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

It is widely distributed in the northern temperate and subarctic zones, southwards to Arizona, the Mediterranean, Turkey, the Himalaya, and China. In the Himalaya, it grows in grasslands, open areas, and shrubberies at elevations between 2,400 and 5,000 m.

In the West, this species is very commonly cultivated as an ornamental. In Nepal, juice of the root is used for indigestion. The leaves can be used as a substitute for tea. Dried leaves and branches are burned as incense.

The formerly accepted variety pumila of Central Asia is today included in D. dryadanthoides (above).

Inflorescences are terminal or axillary clusters, flowers to 3 cm across, stalk densely hairy, farinose, to 3 cm long, bracts reddish-brown, linear-lanceolate, to 2 cm long, tip pointed, sepals pale green, reddish, or purple, triangular-ovate, to 1.5 cm long, tip long-pointed, alternating with the white or red, obovate petals, to 1.5 cm long, tip rounded. Flowering takes place June-August. The fruit is a cluster of numerous achenes.

It is distributed from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan southwards to northern Pakistan, Ladakh, and northern Himachal Pradesh, eastwards across Xinjiang and Qinghai to Inner Mongolia, growing in dry rocky areas at altitudes between 3,200 and 4,200 m.

The generic name alludes to the many farinose parts of the plant. The specific name probably refers to a Russian colonel, P. Salesov, who conducted surveys of roads in Russian occupied Turkestan in the 1860s. I have not been able to find any other information about him.

The generic name is derived from the Latin filum (‘thread’), pendera (‘to hang’), and ula, a diminutive suffix, thus ‘hanging in thin threads’, alluding to numerous tiny tubers on the root, connected by thin threads.

The popular name refers to the fragrant flowers of this genus.

Stem erect, leafy, to 1.5 m tall, clad in fine brown hairs above. Leaves to 30 cm long, pinnately divided with 3-5 pairs of lateral lobes, very unequal, often tiny, terminal lobe much larger, to 10 cm long, with 3-5 ovate lobes, pointed, margin deeply toothed.

The inflorescence is a terminal, much-branched cluster with numerous cream-coloured, tiny flowers, to 6 mm across, stalks densely hairy, petals elliptic, longer than the sepals. Blooming occurs May-August. The fruit has 5-15 free carpels, style curved.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘clad in’ (hairs), probably alluding to the densely downy stalks in the inflorescence.

Leaves are trifoliate, strongly toothed. Stems are rooting at nodes. The fruit is highly distinctive, receptacle swollen, fleshy, red, with tiny dry carpels on the surface.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for strawberry. The English name is derived from the verb to strew, in allusion to the dense tangle of the plant’s stems, creeping over the ground.

The role of strawberry in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

It is found from Uttarakhand eastwards to Myanmar and south-eastern Tibet, growing in forests and shrubberies, and on shady banks, at elevations between 2,000 and 3,600 m.

The fruit is edible, but not very tasty. In Nepal, juice of the root is given in case of fever.

The specific name honours British botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker (see below).

The same year, he was appointed assistant surgeon on board HMS Erebus, which, together with HMS Terror, departed on a 4-year-long expedition to Antarctica, Tasmania, and New Zealand. He had ample time to pursue his interest in botany, and his collections from the voyage were later described in Flora Antarctica (1844-47), Flora Novae-Zelandiae (1851-53), and Flora Tasmaniae (1853-59).

In 1846, he was appointed botanist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain, working on palaeobotany, searching for fossil plants in the coal-beds of Wales.

From 1847, he spent 4 years in India, mainly collecting plants for the Kew Gardens. On this journey, he described numerous plants new to science, including no less than 22 rhododendron species from Sikkim and other parts of the eastern Himalaya. In Sikkim, he and his companion, British physician Archibald Campbell (1805-1874) of the Bengal Medical Service, were held prisoners by Tsugphud Namgyal, the local ruler. This incident led to the British annexation of the Sikkim lowlands.

Publications from the stay in India include The Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849-51), the series Flora Indica (from 1855), together with Thomas Thomson (1817-1878), a fellow student from Glasgow University, and The Flora of British India, published in 7 volumes (1872-1897).

Hooker also undertook other journeys, to Palestine in 1860, to Morocco in 1871, and to the western United States in 1877.

In 1855, he was appointed assistant-director of the Kew Gardens, and in 1865 he succeeded his father as full director, holding the post for 20 years. He was a close friend of the famous Charles Darwin (1809-1882).

Flowering stems erect, silky-hairy, to 20 cm long, flowers long-stalked, solitary or up to 3 together, to 2.5 cm across, sepals and epicalyx with 5 alternating lobes, lanceolate, entire, pointed, petals white, obovate, tip rounded. Blooming occurs April-August. The fruit is red, rounded, to 1 cm across, ripening June-October.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-eastern Tibet, growing in forests and shrubberies, and on open slopes, at altitudes between 1,600 and 4,000 m.

The fruit is edible, but not very tasty. In Nepal, juice of the plant is given to curb profuse menstruation. Unripe fruits are chewed for blemishes on the tongue.

The specific name is derived from the Latin nubis (‘cloud’ or ‘sky’) and colo (‘to inhabit’). Presumably, the type specimen was collected at a high altitude.

Most species have yellow flowers, some red, orange, or white. A gorgeous species with orange flowers is shown on the page Travel episodes – Chile 2011: The white forest.

At maturity, the fruits of some species are hooked at the apex, an adaptation to seed dispersal. In other species, a silky tuft of brownish hairs grows from the styles, which has given rise to a popular German name of these plants, Petersbart (‘Peter’s beard’), probably referring to St. Peter.

The generic name is the classical Latin name for avens. The English name is derived from the Latin avencia, which was the name of a kind of clover. Why it was applied to these plants is not known.

Flowering stems erect, to 50 cm tall, basal leaves to 30 cm long, pinnately divided, lobes large, paired, rounded, saw-toothed, alternating with much small ones, margin hairy, terminal lobe much larger, with 3-5 toothed lobes. Stem leaves few, very small.

Inflorescences are terminal, few-flowered clusters of erect or nodding flowers, corolla to 4 cm across, calyx-lobes short, triangular, green above, purple below, petals 5, usually yellow, sometimes red, rounded. Blooming occurs June-August. The fruit is a globular cluster of hairy achenes.

In Nepal, pounded leaves are applied to wounds.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tall’.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to central Nepal, found in forests and shrubberies at altitudes between 1,800 and 3,600 m.

The specific name was given in honour of British surgeon and naturalist John Forbes Royle (1798-1858), who is chiefly known for his works Illustrations of the Botany and other branches of Natural History of the Himalayan Mountains, and Flora of Cashmere.

European botanists will notice that this plant is very similar to the wood avens (G. urbanum) of Europe.

There are usually 5 petals and sepals, the sepals alternating with 5 epicalyx-lobes. The fruit is a globular head of dry carpels, each with a single nutlet.

The generic name is derived from the Latin potens (‘strong’ or ‘powerful’) and illa, a diminutive suffix. It alludes to the alleged powerful tonic and astringent properties of these plants.

The popular name is an Anglicization of the Latin quinque (‘five’) and folium (‘leaf’), thus ‘five-leaf’ – a name, which was originally referring to those species of the genus, which have 5 finger-like leaflets. Today, however, the name refers to the entire genus.

Stems slender, creeping, often reddish, sparsely hairy, rooting at the nodes. Basal leaves in a rosette, with a stalk to 20 cm long, pinnately divided, leaflets 5-11 pairs, ovate or elliptic, saw-toothed, densely silvery-hairy beneath, to 2 cm long and 1 cm broad, alternating with tiny leaflets. Stipules large, rounded. Flowers solitary, axillary, long-stalked, to 2.5 cm across, stalk to 8 cm, petals 5, yellow, obovate, tip blunt. Flowering occurs June-August. Achenes are hairy.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ‘relating to Anser’ (geese), like one of the common names presumably alluding to geese eating the leaves. The other common name refers to the leaves being silvery-hairy beneath.

Inflorescences are terminal, stalked, with 2-3 flowers. Sepals and epicalyx-lobes almost similar, triangular-lanceolate or elliptic-ovate, silvery-hairy, corolla to 4 cm across, petals 5, obcordate, colour varying from yellow, orange, or blood-red to purple, stamens yellow or purple. Flowering takes place between May and August.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards to Sikkim and south-eastern Tibet, growing in shrubberies and meadows, and on open slopes, at elevations between 2,300 and 4,600 m.

In Nepal, a paste of the root is applied in case of toothache.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek argyros (‘silver’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), alluding to the silvery-hairy leaves.

Plants with blood-red flowers were previously regarded as a separate species, P. atrosanguinea.

Stems several, creeping, ascending, or sometimes erect, to 15 cm long/tall, basal leaves to 16 cm long, including stalk, blade with 2-8 pairs of opposite, broadly ovate leaflets, twice pinnately divided, looking much like leaves of coriander (Coriandrum sativum, Apiaceae), reflected in the specific name. Stem leaves 1 or 2, similar.

Inflorescences are terminal, flowers solitary or up to 3 together, to 1.5 cm across, sepals and epicalyx similar, triangular-ovate, pointed, hairy, petals white, purplish-red at the base, obovate, notched. Flowering occurs July-September.

Inflorescences are terminal, flowers solitary or 2 together, to 2.5 cm across, sepals pale green, triangular, pointed, epicalyx-lobes dark green, oblong-elliptic, blunt. Petals 5, broadly obovate, yellow, slightly longer than sepals. It blooms June-September. Achenes are numerous, covered in silky hairs.

It is distributed from Kashmir eastwards to Bhutan and south-western China, growing at altitudes between 2,400 and 4,900 m. Habitats include meadows, rocks, and forest edges.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wedge-shaped’, alluding to the leaflets.

Stem erect or ascending, to 12 cm tall, downy or almost smooth, basal leaves to 7 cm long, including stalk, blade trifoliate, leaflets obovate, elliptic, or rhombic, white-woolly or sometimes almost smooth on both sides, base wedge-shaped, margin entire on inner half, with 5-7 toothed lobes on outer half, teeth ovate or elliptic, tip pointed or sometimes blunt, stem leaves similar, but much smaller, sessile.

Inflorescences are terminal, flowers solitary or up to 3 together, to 2.5 cm in diameter, sepals triangular-ovate, tip pointed, epicalyx segments oblong or elliptic, largely similar to sepals. Petals yellow, broadly obovate. Flowering takes place May-September. Carpels are densely hairy.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek erion (‘wool’) and karpos (‘fruit’), alluding to the hairy carpels.

Flowers are solitary, axillary, to 2.5 cm across, stalk long, hairy, sepals ovate, hairy, long-pointed, epicalyx-lobes obovate, margin with 3-5 teeth, tip blunt, petals 5, yellow, rounded. Blooming occurs April-August. The fruit is red, strawberry-like, but dry and tasteless, to 2 cm across, ripening May-October.

It is widely distributed in open areas, including grassy slopes and along trails, from Afghanistan eastwards to northern China, Korea, and Japan, southwards to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines. In the Himalaya, it grows at altitudes between 500 and 3,100 m.

In India, the plant is used for fever and infections, and as an anti-coagulant.

The obsolete generic name refers to French botanist and horticulturist Antoine Nicolas Duchesne (1747-1827), professor at Versailles. He was the first botanist to describe strawberries, and he published two works, Histoire naturelle des Fraisiers (1766) and Sur la formation des jardins (1775).

Inflorescences are terminal or axillary, with few long-stalked flowers, to 1.5 cm across, margin of sepals and epicalyx usually entire, petals obovate or rounded, yellow. Flowering occurs June-August.

It is distributed from Himachal Pradesh eastwards to northern Indochina and south-western China, growing in open forests and shrubberies, and on grassy slopes, at elevations between 1,200 and 4,800 m.

The plant is of widespread medicinal usage in India. In Nepal, the juice is used for cough, colds, and stomach problems. The powdered root is kept in the mouth in case of toothache. Juice of the root is taken for peptic ulcer, and to expel intestinal worms.

It is not clear what the specific name refers to.

A densely tufted or mat-forming plant, stems erect, to 5 cm tall, downy. Leaves densely pinnate, basal leaves with stalk to 6 cm long, leaflets 2-9 pairs, packed densely together, pointing forward and twisted upwards, ovate, elliptic, or oblong, silky-hairy beneath, to 4 mm long and 2.5 mm broad, margin densely lobed. Stem leaves usually absent, but if present small, with entire margin. Flowers solitary, to 3 cm across, petals 5, rounded to obovate, yellow, much longer than the triangular, pointed sepals. Blooming takes place June-August.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek mikros (‘small’) and phyllon (‘leaf’).

It looks like a larger edition of P. microphylla, stems erect, downy, to 35 cm tall, leaves pinnate, basal leaves with stalk to 25 cm long, leaflets 10-21 pairs, overlapping, mostly oblong, toothed, densely silky-hairy beneath, hairy or hairless above, to 3 cm long and 1.5 cm broad, stem leaves much smaller.

Inflorescences are few-flowered, flowers to 3.5 cm across, stalk to 5 cm long, sepals triangular-ovate, silky-hairy, epicalyx oblong, margin entire or 2-4-lobed, petals 5, elliptic to obovate, longer than sepals, yellow. It blooms June-September. Achenes are dark brown or blackish, to 2 mm across, forming what looks like a fruit of bramble (Rubus fruticosus) (see photo below). They ripen August-November.

In Nepal, a paste of the root is given to curb profuse menstruation. Leaf buds are boiled, and the water used for bathing in case of fever.

The specific name is Latin, literally meaning ‘pertaining to the foot’, but in a botanical context alluding to a long stalk, in this case the flowering stem.

The fruit, called a hip, is highly distinctive, globular, elliptic, ovoid, or flask-shaped, with numerous carpels clustered inside the fleshy receptacle, each with 1 nutlet. The calyx is often persistent.

These plants are widely distributed in temperate and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with a few tropical species in eastern Africa and southern and south-eastern Asia. 4 wild species occur in the Himalaya, and several others are cultivated as ornamentals.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of these plants, derived from Ancient Greek rhodon (‘rose’), probably of Persian origin.

The flower-stalk is glandular, flowers fragrant, many in terminal clusters, each to 5 cm across, petals 5, obovate, white, sepals 5, lanceolate, long-pointed, downy, often with a few lobes. Flowering occurs April-June. The hip is globular or ovoid, purplish-brown or dark red, to 1.5 cm across, hairless, shining, calyx soon falling. It ripens June-November.

It grows in forests and shrubberies at elevations between 1,200 and 2,800 m, from Pakistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China.

The fruit is edible.

The specific name commemorates Scottish botanist Robert Brown (see Delphinium brunonianum above).

Stems erect, robust, to 5 m long, dark red or purple, prickles few, straight, mostly in pairs below leaves. Leaf-stalk downy, sparsely glandular-hairy, sometimes prickly, leaves pinnate, to 20 cm long including stalk, leaflets 7-11, oblong or elliptic-obovate, pointed, toothed, hairy and glandular beneath, to 6 cm long. Stipules ovate, usually hairless, margin glandular, toothed.

Flowers are solitary or 2-3 together, to 7 cm across, sepals 5, ovate-lanceolate, long-pointed, to 5 cm long, with leafy tip, petals 5, obcordate, pink or red. Blooming takes place June-July. The hip is flask-shaped, usually red, sometimes purplish-red, to 5 cm long, bristly-hairy, shining, calyx persistent, erect. The ripening period is from August to November.

This species is often planted as a hedge. The fruit is edible. In Nepal, a paste of the fruit is eaten, as it is believed that this will improve the eyesight. The foliage is lopped for fodder.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek makros (‘long’ or ‘large’) and phyllon (‘leaf’).

The flower-stalk is smooth, flowers solitary, axillary, white or cream-coloured, to 6 cm across, sepals 4, elliptic, long-pointed, margin entire, petals 4, obovate or obcordate. Flowering takes place between May and August. The hip is globular or pear-shaped, bright red, orange-red, or sometimes purplish-brown, to 1.5 cm across, hairless, calyx persistent, erect. It ripens July-September.

This species is found at altitudes between 1,700 and 4,600 m, from Himachal Pradesh eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China. It grows in shrubberies and open areas.

In Nepal, it is often planted as a hedge, and domestic animals feed on the leaves. The fruit is edible. A paste of the flowers is applied in case of headache, and also taken for liver problems.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek serikos (‘silky’). What it refers to is not obvious.

An erect shrub to 3 m tall, stems slender, purplish-brown. Prickles scattered, straight, stout, yellow, often in pairs beneath the leaves. Leaf-stalk hairless, with a few small prickles, leaves pinnate, to 4 cm long including stalk, often turning pinkish, leaflets 5-9, rounded, toothed near the tip, to 2 cm long and 1.2 cm broad, tip blunt. Stipules ovate, pointed, margin glandular.

Flowers numerous, to 7 cm across, sepals 5, triangular-lanceolate, long-pointed, glandular, petals 5, broadly obovate, pink or reddish. They appear from June to August. The hip is globular, ovoid, or flask-shaped, bright red, to 3.5 cm long, calyx persistent, spreading. Ripening period is July-September.

The fruit is edible.

The specific name was given in honour of English botanist Philip Barker Webb (1793-1854), who collected plants in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, the Canary Islands, and Brazil.

The fruit is highly distinctive, a globular head on the domed tip of the flower-stalk, consisting of fleshy carpels, usually with many nutlets.

Flowers to 2.5 cm across, stalked, solitary or up to 8 together in terminal or axillary, drooping clusters, to 6 cm long. Calyx-lobes broadly ovate, pointed, woolly-hairy, to 8 mm long and broad, petals white, obovate, to 8 mm long, stamens shorter than petals. Blooming occurs April-June. The yellow or orange fruit is enclosed in the calyx, to 1.8 cm across, ripening June-August.

It is distributed from Kashmir eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China, growing in forests and shrubberies, and on open slopes, at altitudes between 1,500 and 3,500 m.

The fruit is edible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with 2 flowers’ – an odd name, as the flowers are often solitary or in clusters up to 8.

Stems creeping, bristly, to 3 m long, rooting at the nodes, lateral stems ascending, to 20 cm tall. Leaves simple, hairy, toothed, sometimes with 3-5 lobes, to 6 cm across, leaf-stalk to 10 cm long, bristly-hairy. Stipules ovate, to 1.3 cm across.

Flowers are erect, solitary or in pairs, to 3 cm across, stalk to 5 cm long, bristly-hairy, sepals leaf-like, ovate or elliptic, to 1.4 cm long and 1.1 cm broad, entire or toothed, petals white. Flowering occurs May-July. The fruit is scarlet, globular, to 1.4 cm across, ripening September-November.

The fruit is edible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with a prominent calyx’.

Flowers to 1.5 cm across, in dense terminal or axillary clusters, to 4 cm long, sepals shorter than petals, woolly-hairy, petals white, sometimes pink. Flowering occurs in winter and spring, between December and April. The fruit is golden-yellow, to 1 cm across, ripening April-July.

It is distributed from Pakistan eastwards to China, and thence southwards to southern Indochina and the Philippines. In the Himalaya, it grows in shrubberies and open areas at elevations between 600 and 2,600 m.

This species is planted to prevent soil erosion. Goats and sheep browse on the leaves. The fruit is sweet, eaten fresh or as marmalade. Medicinally, it is used for various ailments, including fever, diarrhoea, gastric problems, colic, cough, and dysentery. A paste of the root is applied to wounds.

The specific name refers to the leaf shape.

Inflorescences are axillary or terminal clusters, to 7 cm long, with few flowers, to 1.5 cm across, sepals ovate, pointed, woolly-hairy, petals pink, obovate. It blooms April-May. The fruit is red or orange, to 1 cm across, ripening July-September.

This plant is native from eastern Afghanistan eastwards to central Nepal, growing in shrubberies and open areas at altitudes between 1,500 and 2,800 m.

The fruit is edible, with a slightly acid taste. Jam is also made from it.

The specific name was given in honour of German physician and botanist Werner Friedrich Hoffmeister (1819-1845), who accompanied his friend, Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Waldemar of Prussia (1817-1849), as a personal physician on an expedition to India 1845-46. He was killed in Punjab in a skirmish with Sikhs. Hoffmeister collected numerous plants during the expedition, many of which were new to science. His material was published in 1853, titled Die Botanischen Ergebnisse der Reise seiner königl. Hoheit des Prinzen Waldemar von Preussen in den Jahren 1845 und 1846 (‘Botanical results of the travels of His Royal Highness Prince Waldemar von Preussen in the years 1845 and 1846’).

It is distributed from Uttarakhand eastwards to Sikkim, growing in grasslands and shrubberies, and on rocks, at elevations between 2,100 and 3,200 m. It is very common in Nepal.

The fruits are edible and sweet.

A scrambling shrub to 3 m long, stems waxy, purplish, usually with curved, purplish prickles. Leaves pinnate, leaflets 3-9, elliptic, shining, toothed, woolly-hairy beneath, margin toothed, tip pointed or blunt, terminal leaflet short-stalked, to 4 cm long, sometimes lobed, a little larger than the stalkless lateral leaflets.

Flowers grow to 1.6 cm across, arranged in branched, short, axillary or terminal clusters, calyx-lobes purplish, silky-haired, long-pointed, about same length as the pink petals. Flowering occurs April-July. Initially, the fruit is red, turning to purplish-black, to 1.2 cm across, ripening July-September.

The fruit is edible. In Nepal, unripe fruits are chewed to relieve headache.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘relating to snow’ – an odd name, as it is not found at particularly high altitudes. Maybe it alludes to the waxy stems.

This description includes R. foliolosus, which was previously regarded as a separate species.

Inflorescences are terminal or axillary clusters, the terminal one very long, to 24 cm, flowers to 1.8 cm across, sepals ovate or lanceolate, to 7 mm long and 4 mm broad, pointed, petals white or yellowish, oblong, to 8 mm in diameter. Blooming takes place June-August. The fruit is dark red or blackish-purple, to 1 cm across, ripening July-October.

This plant is found in forests and shrubberies at elevations between 1,500 and 3,200 m, from Pakistan eastwards to Myanmar and south-western China.

Fruits are edible. In Nepal, a paste of the bark is applied to skin problems, a paste of the leaves to sprains.

The specific name is Latin, referring to the inflorescence.

Stems to 6 m long, reddish-brown, initially downy, later smooth, with few prickles. Stipules linear or linear-lanceolate, to 8 mm long, soft-haired. Leaves stalked, trifoliate, rarely with 5 leaflets, rachis with a few minute prickles, leaflets ovate, rarely ovate-lanceolate, to 6 cm long and 4 cm wide, densely woolly-hairy beneath, base heart-shaped or rounded, margin irregularly toothed or double-toothed, tip pointed.

Inflorescences are few-flowered, flowers stalked, to 2 cm across, sepals ovate-lanceolate, to 1.5 cm long, purplish, margin downy, tip long-pointed, petals pink, ovate, to 1 cm long and 6 mm wide, tip entire or indented. The flowering period is May-August. The fruit is black, ovoid or globular, ripening July-October.

The fruit is edible. In Nepal, juice of the leaves is taken for fever.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘stalked’. What it refers to is not clear. The flowers are not particularly long-stalked.

These plants resemble species of Potentilla (above), but the leaves are wedge-shaped, trifoliate or palmate.

The generic name commemorates Scottish physician and antiquary Robert Sibbald (1641-1722), who is best remembered for being the first person to describe the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), from a specimen stranded in the estuary of the Firth of Forth, Scotland, in 1692. Initially, it was referred to as Sibbald’s rorqual.

Inflorescences terminal, flat-topped clusters, flowers to 7 mm across. Sepals and epicalyx similar, ovate or oblong, silky-hairy, tip pointed, petals 5, obovate, pale yellow, similar in size to sepals, tip blunt. Flowering takes place May-August. The achenes are smooth.

It is distributed from Afghanistan eastwards along the Himalaya to central China and Taiwan. In the Himalaya, it grows in grasslands and rocky areas, found at altitudes between 3,000 and 4,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wedge-shaped’, referring to the leaves.

The generic name is composed of the genus name Sibbaldia (above), and probably Ancient Greek antheros (‘anther’), thus ‘with anthers like Sibbaldia‘.

Flowering stems several, prostrate or ascending, to 20 cm tall/long. Leaves pinnate, including stalk to 8 cm long, blue-green, leaflets 3-8 pairs, elliptic or obovate, to 1.5 cm long and 8 mm broad, tip blunt, pointed, or sometimes with two forks. Flowers solitary or few together, yellow, to 1.5 cm across, short-stalked, petals obovate, rounded, sepals and epicalyx-lobes elliptic or ovate, pointed. Blooming takes place May-September.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘two-forked’, presumably alluding to the leaflets, which often have two teeth.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek gala (’milk’), alluding to the usage of yellow bedstraw (G. verum) in rennet, as its flowers are able to coagulate milk to make cheese. In his book Herbal Simples, Dr. William T. Fernie (1830-1914) writes: “The people in Cheshire, especially about Nantwich, where the best cheese is made, do use it [yellow bedstraw] in their rennet, esteeming greatly of that cheese above other made without it.”

In Norse religion, yellow bedstraw was dedicated to Frigg, goddess of knowledge, love, and marriage, who was also protector of women giving birth. It was a custom to line the childbed with this fragrant herb. When Christianity was introduced, this heathen habit was banned, but as it persisted, the Church decided to dedicate yellow bedstraw to Virgin Mary instead, claiming that this herb was lining the crib of the newborn Jesus, hence the folk name Our Lady’s bedstraw.

It was also stuffed into mattresses, from which the coumarin of the drying plants would emit a pleasant fragrance. As coumarin is toxic, it would also expel fleas and lice.

Inflorescences are terminal, or sometimes in axils of upper leaves, spreading, with up to 10 stalked flowers, corolla white, sometimes pale green, to 3 mm across, petals 4, ovate, pointed. Flowering takes place April-August. The fruit is ellipsoid, to 2 mm across, with a dense cover of white hairs.

It is widely distributed in forests and shrubberies, from Afghanistan eastwards to China and Korea, in the Himalaya found up to elevations around 4,000 m.

The specific name was given in honour of German physician and botanist Werner Friedrich Hoffmeister (1819-1845), who accompanied his friend, Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Waldemar of Prussia (1817-1849), as a personal physician on an expedition to India 1845-46. He was killed in Punjab in a skirmish with Sikhs. Hoffmeister collected numerous plants during the expedition, many of which were new to science. His material was published in 1853, titled Die Botanischen Ergebnisse der Reise seiner königl. Hoheit des Prinzen Waldemar von Preussen in den Jahren 1845 und 1846 (‘Botanical results of the travels of His Royal Highness Prince Waldemar von Preussen in the years 1845 and 1846’).

These plants were formerly included in the genus Randia, erected by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) to commemorate English botanist and apothecary Isaac Rand (1674-1743), director at the Chelsea Physic Garden. Thus, the generic name means ‘the Randia from the Himalaya’.

A small many-branched shrub, to 2 m tall, branches sometimes ending in a straight spine. Leaves crowded at the end of branches, to 3 cm long, narrowed to a short stalk, blade ovate, oblanceolate, or elliptic, smooth, margin entire, tip rounded or pointed.

Flowers solitary, to 1.2 cm long and 1 cm in diameter, calyx-tube to 1 cm long, with 5 narrow, pointed, reflexed lobes, to 1.5 mm long. Corolla fragrant, greenish-white or yellow, funnel-shaped, tube to 8 mm long, with 5 reflexed, pointed lobes, to 5 mm long, stigma and anthers exserted, stigma white or yellowish, spindle-shaped, anthers long, brownish with darker longitudinal streaks. Flowering occurs April-July. The fruit is globular, to 8 mm in diameter, purple or blue, calyx persistent.

In Nepal, the wood is used as fences, walking sticks, and fuel. Goats and sheep browse on the foliage. A paste of the charcoal is applied to extract spines that have been buried deep in the flesh.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek, meaning ‘with 4 seeds’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek leptos (‘thin’) and derma (‘skin’). It is not obvious what it refers to.

Branches are long or short, purplish or grey, with glandular hairs. Leaves sessile or short-stalked, oblong-lanceolate or ovate-lanceolate, to 10 cm long and 2.5 cm wide on long branches, much smaller on short branches, hairy, margin entire, hairy, tip pointed, midrib indented, stipules triangular, to 4.5 mm long.

Flowers are axillary or terminal, up to 5 together, calyx tube to 4 mm long, with 5 triangular lobes, to 1.5 mm long, hairy, pointed, corolla funnel-shaped, to 1.5 cm long, white or pink, turning violet or purplish with age, hairy in the throat, with 5 ovate lobes, to 1 cm long, abrupty narrowed to a sharp point. Flowering occurs June-October. The fruit is a shining capsule, stinking when crushed.

The specific name refers to Kumaon, a district in Uttarakhand. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

The generic name is derived from the Latin luculentus (‘brilliant’), ultimately from lux (‘light’).

The inflorescence is a terminal, many-flowered, spreading cluster, calyx lobes lanceolate, pointed, to 1.6 cm long, hairy, corolla pink, sometimes white, with a narrow tube, to 5 cm long, lobes rounded, to 1.5 cm across, margin with a few tiny teeth. Flowers occur September-October.

This beautiful plant is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to northern Indochina and south-western China, growing in shrubberies and open areas at elevations between 800 and 2,400 m. It is rather common in Nepal.