Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Guatemala 1998: Country of the Mayans

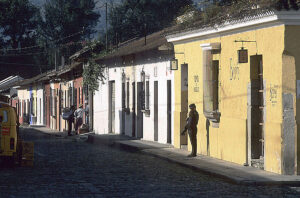

As Guatemala City is not a particularly interesting place, we hurry on to the former capital of the country, the gorgeous old Spanish colonial town of Antigua, with cobbled streets, pastel-colored houses, arches across the streets, and a huge number of spectacular churches.

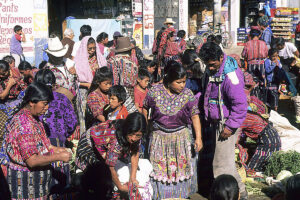

The markets in Antigua are a blaze of colours. Almost all women wear a colourful blouse, called huipil, consisting of several layers of cloth, sown together into intricate patterns. Every village in Guatemala has its own distinct huipil colours and patterns, and almost every woman weaves the cloth for her huipil herself.

These gorgeous blouses are not only worn at religious festivals or other important events, as one might judge from the beauty of them, but constitute a part of the daily dress. The men’s traditional garment is also very distinct, as they wear pyjama-like trousers, often with local patterns and colours.

Their temples were huge limestone pyramids, where priests made numerous sacrifices, including human, to the Mayan gods. However, these people were also intellectuals, being excellent mathematicians and astronomers, whose calendar, it seems, was more accurate than the Gregorian.

Ruins of ancient Mayan cities are dotted all over southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. The most famous are Chichen Itza in Mexico, Tikal in northern Guatemala, Caracol in Belize, and Copàn in Honduras.

We keep a sharp lookout for an endemic bird, the Atitlán grebe (Podilympus gigas), but in vain. Formerly, this species was quite common in the lake, but it began to decline in 1958, when two species of bass (Micropterus) were introduced into the lake for the game fishing industry. These species of fish, which are highly invasive, ate many of the crabs and fish, which the grebes depended on for food, and the bass even killed grebe chicks.

The Atitlán grebe was also polluted genetically, as a near relative, the pied-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps), immigrated to the lake around the 1960s, and the two species began to interbreed. The population of the Atitlán grebe declined from c. 200 in 1960 to 80 in 1965.

Conservation efforts of biologist and author Anne LaBastille (1933-2011) had the effect that the population increased to 210 individuals by 1973. Unfortunately, a powerful earthquake in 1976 drained the area, where the grebe had recovered, causing the species to become extinct around 1990.

Not far from the lake is the town of Solola, in which an interesting and colourful market takes place every Tuesday and Friday.

Unfortunately, our visit coincides with an unusually powerful hurricane, named Mitch, which ravages Central America between October 29 and November 3, dumping extreme amounts of rain. (Unofficial reports later said about 1,900 mm.)

Throughout the horse race, rain is pouring, and it becomes a rather muddy affair. Nevertheless, it is carried out as planned, and numerous spectators are watching it, despite the rain.

He was wondering why these, often gigantic, structures were built at all, and why they were always erected on spots with high electromagnetic energies. His work has led him to believe that these structures, which were often built during periods of famine, were erected to increase the yield of crops.

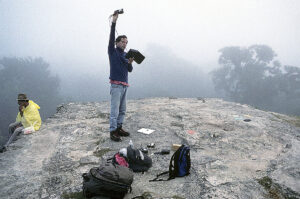

He now wants to visit the Mayan ruins in Tikal National Park to carry out measurements of telluric ground currents and airborne electric charge at some of these ancient megalithic structures.

When the ruins of Tikal were re-discovered in the 1850s, they were overgrown by thick rainforest, but most ruins have now been cleared of vegetation. Today these ruins, and a large tract of jungle around them, have been declared a national park. This jungle is host to an incredible wealth of plants and animals, including the jaguar (Panthera onca), which was a fertility symbol of the Mayans.

As electromagnetic energies are strongest just before dawn, John, Geoff and I set out with a local guide, Luiz, at 3:30 in the morning. In the dark tropical night, the dense rainforest is looming over us. Decaying vegetation emits a distinct smell, mixed with the fragrance from flowers and herbs. Insects call incessantly, and a coughing roar announces that a jaguar is on the prowl.

Even at this early hour, our clothing is drenched in sweat, sticking to our bodies. To catch our breath, we take a break on a wall between two of the Mayan ruins, brooding silently in a moonlit fog, The Temple of the Great Jaguar, which has been dubbed ‘Queen’s Pyramid’, and Temple II, popularly called ‘King’s Pyramid’.

Re-entering the pitch-dark rainforest, we follow the winding trail, emerging onto a small plateau, known as El Mundo Perdido (‘The Lost World’). At this moment, John’s readings of airborne electric charge, recorded by his electrostatic voltmeter, suddenly leaps way beyond anything he has ever measured before.

With the deep-throated roars of golden-mantled howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata), surrounding us in the pre-dawn darkness, we watch the already striking readings growing even stronger, as we approach the Lost World Pyramid, then rising again as we ascend its oversize steps.

[On this old pyramid, John got amazing results, supporting his theory that many ancient structures were built to increase crop yields. He now felt that he had enough material to publish a book about his ground-breaking theories concerning natural earth energies. The entire text of this book, which I assisted him in producing, is published elsewhere on this website, see Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty. Other of John’s theories are dealt with on the page People: John Andrew Burke.]

The rainforest is teeming with birds, including the splendid ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata), a rare gamebird of Central America, which has been hunted almost to extinction. In Tikal, however, it is very confiding, as no hunting takes place here.

We also observe two species of fruit-eating toucans, the large keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus) and the smaller collared araçari (Pteroglossus torquatus). Other birds include groove-billed ani (Crotophaga sulcirostris), of the cuckoo family (Cuculidae), brown jay (Psilorhinus morio), roadside hawk (Buteo magnirostris), and the large gamebird-like crested guan (Penelope purpurascens), which belongs to the family Cracidae.

Various birds are feeding in ponds and swampy areas, including grey-necked woodrail (Aramides cajanea) and northern jacana (Jacana spinosa), the latter having a spur on its wing, reflected in the specific name.

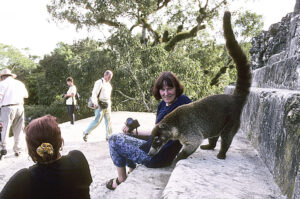

Another confiding species is the grey fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), which we also often observe among the ruins. A fairly large rodent, the Central American agouti (Dasyprocta punctata), is rather common on the forest floor, whereas bands of Central American spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) jump about like acrobats in the trees, using their long tail as a fifth limb.

Morning and evening, the forest reverberates from the incredibly powerful call of the howler monkeys, and one evening we observe a relative of the coati, a kinkajou, or honey bear (Potos flavus), feeding in a tree near our lodge.

Black vultures (Coragyps atratus) are often perched on poles along the shore, looking for food scraps, dead fish, or other animals, which have been washed up on the beach. They are not exactly beauties! This species is widely distributed in America, from the south-eastern United States southwards to central Chile and Uruguay.

In many places, the beach is covered in huge growths of beach morning-glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae) with large, beautiful flowers. This proliferous plant is widespread on tropical beaches around the world. Together with many other members of the morning-glory family, it is described on the page Plants: Morning-glories and bindweeds.

We pay a visit to a breeding centre, where threatened animals like green iguana (Iguana iguana), spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) are reared, later to be released into nature.

In this scrubland, we observe three members of the tyrant-flycatcher family (Tyrannidae), scissor-tailed flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus), which, as the name implies, has a long, forked tail, the pale yellow tropical kingbird (Tyrannus melancholicus), and the bright yellow great kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus).

In the evening, lesser nighthawks (Chordeiles acutipennis) fly about over the vegetation, hunting for insects.

In areas of stagnant water, we observe hundreds of bladderworts (Utricularia). These fascinating flesh-eating plants are described in depth on the page Plants: Carnivorous plants.

The mangrove is home to many birds, including osprey (Pandion haliaetus), great white egret (Ardea alba), tricoloured heron (Egretta tricolor), yellow-crowned night-heron (Nyctanassa violacea), and green heron (Butorides virescens). We also observe a single black Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata). This large duck was domesticated at an early stage and has since been introduced to most parts of the world. It is described on the page Animals – Animals as servants of Man: Poultry.

Whereas Lotte travels to Honduras to visit the Copàn Mayan ruins, I board a bus, bound for a cloud forest named Biotopo del Quetzal. The word quetzal refers to a gorgeous species of trogon, the resplendent quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno). This magnificent bird is the national bird of Guatemala, whose image is found on the country’s flag and coat of arms, and which also lends its name to the Guatemalan currency.

During the following days, I roam the cloud forest, hoping to observe this legendary bird. The vegetation here is indeed lush, the huge trees festooned with epiphytes: mosses, lichens, ferns, and various seed plants, mostly bromeliads, of the pineapple family (Bromeliaceae), and orchids.

I observe very few birds in the forest, and no quetzal. On my last day in the area, I return to the small lodge at the road side, rather disappointed that I didn’t succeed in observing this enigmatic bird. I take my seat at one of the outdoor tables to enjoy a cup of coffee, when the lodge owner, who is fiddling with something in his car engine, points to a group of trees, uttering only one word: “Quetzal!”

There, high up in a tree, sits a gorgeous male resplendent quetzal, and, what is more important, it is not moving. Here is my chance to get photographs! I sneak closer to the tree, but from this angle a photograph of the bird is not possible. I shall have to do with pictures from the road, far away or not.

Now, however, another problem occurs: The wife of the lodge owner is cooking lunch, and the smoke from the cooking is drifting past the tree, where the bird is sitting, making my pictures hazy. I must wait for breaks in the puffs of smoke to take my pictures, but luckily the quetzal is still not moving. Trogons are rather lethargic birds.

Finally, I manage to get a few photographs, but definitely nothing to brag about!