Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Flora of the Alps and the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees is a mountain range in southern France and northern Spain, extending nearly 500 km from near the Atlantic Ocean eastwards to just north of Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast. The highest peak is Aneto (3404 m), in the central part. Most of the way, the main crest of the range constitutes the border between Spain and France, with the small independent state Andorra situated between the two countries.

Both mountain ranges are home to an astounding number of seed plants. No less than c. 4,500 species have been encountered in the Alps, of which c. 360 are endemic, whereas the Pyrenees is home to about 3,500 species, of which c. 200 are endemic. These numbers, however, include all species growing in the lower valleys, many of which are widespread in Europe.

Paula Kohlhaupt’s way of taking pictures of plants in their natural surroundings was very inspiring. In many of the pictures, the background was dramatic rock faces or mountain slopes, and if the plant was depicted close-up, she saw to it that the background or other elements would not disturb the motive.

During my first botanical travels to the Alps, in 1968 and 1970, I tried to take pictures in a similar way. As a rule, however, the result was poor, mainly because I would often fail to notice disturbing elements in the pictures. Later, my attempts improved, and the pictures on this page show a selection of my photos from later trips to the Alps, and a single late-summer visit to the Pyrenees.

Below, the plants are presented alfabetically according to family name, genus name, and specific name. At the bottom of the page, some botanical terms are explained.

The inflorescence of these plants is very distinctive, consisting of a compact globular umbel on an unbranched stem. Initially, the umbel is enclosed in a papery spathe, which splits into lobes, when the stalked flowers unfold.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of garlic (A. sativum), described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

In the Alps, it grows up to elevations around 2,800 m.

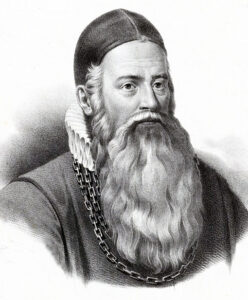

This plant is rich in vitamins and was formerly also widely used as a medicinal herb, mentioned as early as in 1543 by German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs (see below).

It also has its role in folklore. In Strasbourg, in 1669, an herbal witch mentions that if a cow had been bewitched and did not give milk, you must stroke it three times with a chive bulb, while saying: “Oh, dear cow, give me my milk, which is so good for me, and which our dear Lord Jesus Christ has given me.”

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek skhoinos (‘rush’, genus Juncus), and prason ‘leek’, thus ‘rush-like leek’, naturally referring to the shape of the leaves.

For 2 years, he practiced as a doctor in Munich, until he was offered the chair of medicine at the University of Ingolstadt. This university was firmly Roman Catholic, which created problems for Fuchs who had Lutheran views. Therefore, in 1528, he accepted a position as personal physician to Georg der Fromme (George the Pious, 1484-1543), Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, who was a Protestant.

In 1533, Fuchs was called to Tübingen by Ulrich (1487-1550), Duke of Württemberg, to help in reforming the University of Tübingen in the spirit of humanism. Here, he served as professor of medicine for the rest of his life, and he also created the first German garden with medicinal plants.

He published a large number of books on medicinal issues, and also two major botanical works. De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (‘Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants’) was published in Basel in 1542. This work includes about 500 medicinal plants, of which more than a hundred had not been described before. The concomitant illustrations are detailed and lifelike. In 1543, it was translated into German, titled New Kreüterbuch.

The other book is Codex Fuchs (Codex Vindobonensis Palatinus), published in 9 volumes in Tübingen 1536-1566. This work contains 1,529 coloured plates, depicting medicinal plants.

The major part of the information above is from the website en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonhart_Fuchs.

The specific name stems from a Medieval German name of the species, Siegwurz (‘root of victory’). Another old German name was Allemannsharnish (’all people’s armour’), referring to the onion, which is wrapped in a thick layer of bracts. In the Middle Ages, this layer was likened to an armour. Alpine leek was carried by soldiers as an amulet, as it was believed that it would protect the bearer from being wounded.

In his illustrated herbal Neuwe Kreuterbuch (from 1588), German physician and botanist Jakob Dietrich (1525-1590), also called Jacobus Theodorus, but better known under the name Tabernaemontanus, remarks that Alpine leek protects from “all kinds of ghosts and bad spirits.” He continues: “Farmers and herdsmen praises it highly as a protection against all kinds of bad air and vapours.”

The plant was also utilized by Bohemian mine workers as a charm against ‘unclean spirits’.

When building a stable in Vorarlberg, western Austria, a cavity was drilled in the lowest beam, and a bulb of alpine leek was placed in it, which would protect the cattle against being bewitched.

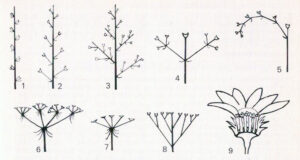

The inflorescence of this family is unique. In almost all species, the flowers are arranged in terminal umbels, which may be simple, usually with bracts at the base, and each of the stalks, the so-called primary rays, ending in a flower. More commonly, the umbel is compound, consisting of a number of primary rays, each ending in a secondary umbel. Each of these umbels usually has small bracts, bracteoles, at the base, and a number of secondary rays, each ending in a flower. Usually, the secondary umbels together form a flat-topped inflorescence, mostly with white, yellow, pink, or purple flowers, rarely blue or bright red. The flowers have five petals and stamens. This also accounts for the sepals, if they are present. They are usually missing, however.

The family name is derived from the name of honey bees, genus Apis, referring to the fact that many plants of the family are much visited by bees and other nectar-sucking insects, in particular hovering flies.

The generic name is derived from the Latin angelicus (‘angelic’), originally from Ancient Greek angelos (‘messenger’), alluding to the healing power of garden angelica (Angelica archangelica). One Middle Age legend has it that an angel had a dream that this herb would cure the plague. According to another legend, angels – or even Archangel Gabriel himself – brought the knowledge of this herb to humans. The medicinal usage of garden angelica is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of woods’. However, it is more commonly growing in open areas, including hedgerows, marshes, and edges of woods and fields.

The generic name is derived from the Latin aster (‘star’), alluding to the open, star-shaped bracts of the inflorescence. The common name is derived from the Latin magister (‘chief, teacher, leader’), alluding to the medicinal usage of the genus. This name also refers to another umbellifer, Peucedanum ostruthium (below), which was once likewise much utilized in traditional medicine.

This species is native to the eastern half of the Alps, where it grows in woodlands, shrubberies, clearings, and along streams, usually on calcareous soils. It is found up to elevations around 2,300 m.

This species is native from the Pyrenees eastwards across the Alps, the Carpathians, and the Balkans to Turkey and the Caucasus. It was introduced to the British Isles in the 16th Century and has become naturalized in several areas. Its natural habitat include montane meadows and other grasslands, forest clearings, and streamsides, usually on calcareous soils. It has a wide altitudinal distribution, found from the lower valleys up to about 2,300 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘greater’, alluding to this plant being larger than the lesser masterwort (below).

It is distributed in the south-western Alps, the northern Apennines, the Pyrenees, and in the northern Iberian provinces of Catalunya and Huesca.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘smaller’, indicating its smaller size compared to the previous species.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’) and pleuron (‘rib’), alluding to the shape of the roots. The name hare’s-ear refers to B. rotundifolium, whose leaves resemble a hare’s ears, whereas thoroughwax is a corruption of a German name of these plants, Durchwachs (‘growing through’), alluding to the stem of some species, which appears to grow through the leaves.

The roots of several species of hare’s-ear are an important ingredient in the traditional Chinese medicine chai hu, utilized for a huge number of ailments, including respiratory problems, dizziness, menstrual irregularity, cough, fever, and influenza. The name literally means ‘kindling of the barbarians’. Presumably, some Chinese observed the ‘barbarians’ using dried hare’s-ear stems as kindling.

This species is widespread in montane areas, from the Pyrenees eastwards to Poland, the Czech Republic, and the northern parts of the Balkans. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to elevations of at least 2,100 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Ranunculus’ (buttercup). It may refer to the flower colour, but many other species of hare’s-ear also have buttercup-yellow flowers.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khairephyllon, from khairo (‘to be glad’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), the classical name of garden chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium), a culinary herb, which is much used in Mediterrenean kitchens. Botanically speaking, however, the word chervil also applies to members of the genus Chaerophyllum.

This plant is partial to humid areas, including wet meadows and along streams, but it may also grow in drier grasslands, especially at higher altitudes. It is distributed in central European mountains, including the Harz, Thuringia, Saxony, the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Apennines, and the Carpathians, and also in montane areas of the Balkans. It occurs eastwards to Ukraine. It grows up to altitudes around 2,000 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘hairy’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eryngion, diminutive of eryngos, the classical name of the sea holly (E. maritimum).

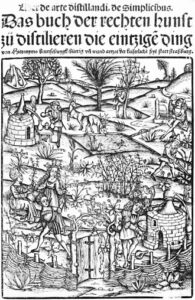

In German, these plants are called Mannstreu (‘faithful to the man’), first mentioned by German surgeon and herbalist Hieronymus Brunschwyg (c. 1450-1512) in his book Liber de arte distillandi de simplicibus (1500), also known as Kleines Destillierbuch (‘small distillation book’).

The origin of this strange name can be traced back to Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.), who mentions a sort of eryngion, which he also calls centum capitum (‘the one with a hundred heads’). He says that, according to local belief, this plant had male and female roots, and that men who possessed a ‘male’ root, would be attractive to women.

In Greek mythology, it was told that the youth Phaon was in possession of such ‘male’ roots, which causedthe female poet Sappho to fall in love with him.

However, Pliny adds that he regards all this as vanitas – pure superstition.

Despite his knowledge of Pliny’s scepticism, German theologist and botanist Otto Brunfels (c. 1488-1534) states the following in an herbal book from 1532: “Welcher mann solich wurtzel bey ym tregt, die ein männlein ist, machet yn holdselig gegen den frawen” (‘The man, who carries such roots on him, which are male, will be attractive to women’).

It was named in honour of a French physician named Bourgat who collected plants in the Pyrenees in the company of botanist Antoine Gouan (1733-1821), who described the species in 1766. A native of Montpellier, Gouan was a pioneer of the Linnaean binominal taxonomy in France. In 1762, he published a plant catalog of the botanical garden at Montpellier, titled Hortus regius monspeliensis.

During the Middle Ages, it was regarded as an aphrodisiac.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘growing on plains’ or ‘growing in fields’.

Stem smooth, leaves bluish-green, 3 or 4 times pinnate, ultimate segments lanceolate or ovate, almost rhombic, toothed, upper leaves much smaller. Bracts few, thread-like, bracteoles numerous, likewise thread-like. Flowers white.

The generic name honours Slovenian pharmacist, chemist, and botanist Žiga Graf (1801-1838), who worked as a pharmacist in Ljubljana. Despite his short life, he wrote a large number of articles on botanical issues.

Some authorities include this species in the genus Pleurospermum (below).

The fruit of these plants is characteristic, strongly compressed and ribbed, the lateral ribs with a broad wing. Inside the fruit are club-shaped resin canals, clearly visible against the light.

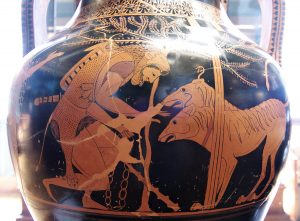

The generic name is a Latinized version of the classical Greek name of a southern European plant, which was utilized in traditional Greek medicine. It was called panakes herakleion, meaning something like ‘the universal healing herb of Herakles’. It was thought that the immensely strong mythological hero Herakles (in Latin Hercules) discovered the medicinal properties of this plant. The generic name was applied in 1753 by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), undoubtedly referring to the profuse growth of many of these plants, likened to the strength of Herakles.

The common name hogweed is variously interpreted, either referring to pigs being fond of eating common hogweed (below), or as a derogatory term, a plant only fit for pigs. Cow-parsnip, used from about 1548, presumably alludes to the plant being eaten by cattle.

This plant, divided into about 16 subspecies, is distributed throughout Europe, eastwards to western Siberia, and also in Morocco, Turkey, and the Caucasus. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to elevations around 2,700 m.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek spondylos (‘vertebrate’), alluding to the segmented stem.

Why the names Laserpitium and laserwort have been applied to this genus is not clear. They are derived from the Latin lacarpicium, the name of a resinous gum with culinary and medical uses, which, in Ancient Rome, was extracted from various genera of Apiaceae, including giant fennel (Ferula) and Silphium, derived from silphion, the classical Greek word for laserwort. One of the usages was as a contraceptive.

This plant is restricted to the southern part of the Alps, from France eastwards to Austria, growing on warm, dry, calciferous slopes.

The specific name honours Swiss physiologist, naturalist and poet Victor Albrecht von Haller Sr. (1708-1777), professor of botany in Göttingen and often referred to as ‘the father of modern physiology’. He was among the first botanists to realize the importance of herbaria to study variation in plants, and, consequently, he included material from different localities and habitats, and in various phases of development.

The genus Halleria, comprising attractive shrubs from southern Africa, was named in his honour by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778).

It is widespread in Europe, only absent from Iceland, the British Isles, the Netherlands, and Greece.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘broad-leaved’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek peukedanos (‘bitter’), alluding to the bitter substances in masterwort (below).

It is native to mountains of central and southern Europe, including the Alps, the northern Apennines, the Carpathians, the French Massif Central, and mountains in the Iberian Peninsula. However, due to its medicinal properties it has been widely introduced elsewhere. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 2,200 m. Its habitats include meadows, grazing grounds, steep slopes, and avalanche gullies.

The common name alludes the multiple usage of this plant. In former days, the root was believed to possess wonderful properties, called remedium divinum (‘divine remedy’) and sold in pharmacies under the names Radix ostruthii or Rhizoma imperatoriae. It was utilized for treatment of disorders of intestines, stomach, kidneys, skin, respiratory tract, and cardiovascular system, and to fight infections, fever, flu, and colds. The plant was also used as a flavouring agent in various liqueurs and bitters.

The name masterwort also applies to members of the genus Astrantia (above).

In Germany, during plague epidemics, burnet-saxifrage was eaten, as it was said to be an effective remedy against the feared disease, and it would also protect you against all kinds of poisons.

The generic name is of unknown origin.

The burnet part of the common name alludes to the similarity of the leaves of some species of the genus to those of burnet (Sanguisorba minor), whereas the saxifrage part refers to the diuretic properties of some species, similar to certain species of saxifrage (Saxifraga).

This species grows in forest clearings, shrubberies, meadows and pastures, and along roads, preferably on nutritious and calcareous soils, from the lower valleys up to altitudes around 2,300 m. It is widespread, from Europe eastwards to the Caucasus.

Formerly, it was used in traditional Austrian medicine for treatment of respiratory problems, fever, infections, colds, and flu.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pleuron (‘ribbed’) and sperma (‘seed’), alluding to the winged fruits of the genus.

Several species are described on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

This species, which grows in open forests, grasslands, and grazing grounds, is partial to calcareous soils. It is distributed in the Alps and the Carpathians, and on the Balkan Peninsula, with isolated populations in the Swabian Jura, Franconia, and Thuringia, and also in Sweden. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to elevations around 1,850 m.

The specific name refers to Austria. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

In Latin, the generic name applies either to the spindle tree (Euonymus), or to a kind of willow (Salix). The connection to these plants is hard to see.

It is distributed in the Alps, the Pyrenees, the Apennines, and in mountains on the Balkan Peninsula, growing on slopes at elevations between 800 and 2,300 m.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek antherikos (‘straw’), alluding to the narrow leaves.

Previously, these plants were placed in the lily family (Liliaceae), but were then moved to a separate family, Anthericaceae, which is today regarded as a part of Agavoideae, a subfamily of the asparagus family.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘lily-like’, naturally alluding to the flowers.

The common name alludes to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), a mystic, an abbot, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the Cistercian Order. He was a co-founder of the Knights Templar, also known as The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, a Catholic military order, founded around 1119 to defend pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. Their headquarters were located on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

This species is distributed in the major part of Europe, southwards to the Mediterranean, eastwards to European Russia and Turkey. It mainly grows in sunny areas and on calcareous soils, in grasslands and forest edges, and on drier slopes. In the Alps, it may be found up to altitudes around 1,900 m.

This genus was established in 1811 by Italian botanist Giovanni Mazzucato (1787-1814), in honour of his patron, Count Giovanni Paradisi (1760-1826), mathematician, politician, and poet.

It grows to about 90 cm tall, with grass-like leaves and pure white, trumpet-shaped flowers, to 6 cm long, with prominent yellow anthers.

Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica (5 volumes dealing with herbal medicine), included this species among his medicinal plants.

The specific name is derived from the Latin lilium (‘lily’), and the suffix aster (‘resembling’).

The common name refers to St. Bruno, founder of the Carthusian order of monks in the 11th Century, in the French Alps.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek asplenon, the classical name of spleenworts, ultimately from splen (‘spleen’), alluding to its usage to cure anthrax in livestock.

It is a very widespread plant, found in all of Europe, eastwards across most of Siberia, in North Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, the Himalaya, and China. In Central Asia, it grows up to elevations around 3,300 m.

The specific and common names refer to the fact that it often grows on walls, and to the likeness of its leaves to those of common rue (Ruta graveolens).

It is very widely distributed, found in scattered locations in most parts of the world, growing in rocky habitats and on walls, from sea-level up to about 3,000 m. It is fairly common in the Pyrenees and the Alps.

This species and its near relatives were much utilized in traditional herbal medicine. Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.) and Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) both distinguished between a pale and a black adianton. They were supposed to possess general anti-toxic properties, used as a diuretic, to expel kidney stones, to cure pulmonary problems, jaundice, spleen diseases, and skin ailments, and to promote hair growth.

The specific name refers to one of the names that the Ancients used for these plants, which were randomly called trichomanes (‘fine hair’), polytrichon (‘many hairs’), kallitrichon (‘fair hair’), and capillus veneris (‘venus hair’).

The inflorescence consists of many individual flowers, called florets, which are grouped densely together to form a flower-like structure, the flowerhead, technically called the capitulum. The flowerhead is surrounded by an involucre, consisting of densely packed green bracts, often erroneously called a calyx. The central disk florets are symmetric, and the corolla is fused into a tube. The outer ray florets are asymmetric, the corolla having one large lobe, which is often erroneously called a petal. In some species, ray florets, or sometimes disk florets, are absent.

In his Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), English herbalist John Gerard (c. 1545-1612) informs us that during the Trojan War the Greek hero Achilles used yarrow to stop bleeding on wounded soldiers. Hence, the name Achillea was applied to the genus by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). It was already mentioned as a medical herb in De simplicium medicamentorum facultatibus, written by Greek-Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Aelius Galenus (c. 129-210 A.D.), also known as Claudius Galenus or Galen of Pergamon.

Various plants, including yarrow, were found in a 50-60,000-year-old Neanderthal grave in Iraq, perhaps indicating that these plants were used medicinally. (Source: G.P. Shipley & K. Kindscher 2016. Evidence for the Paleoethnobotany of the Neanderthal: A Review of the Literature. hindawi.com/journals/scientifica/2016/8927654)

The name yarrow is a corruption of gearwe, an ancient Anglo-Saxon name for common yarrow (below). The name sneezewort refers to Achillea ptarmica, often called sneezeweed, which, if stuck up the nose, causes sneezing. The name milfoil is explained below, at A. millefolium.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ater (‘dark’ or ‘black’), alluding to the dark stems.

It was named by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in honour of Italian pharmacist Nikolaus Clavena (dead 1617), who described the species in 1610. He was the author of Historia Alsinthii Umbelliferi (1610).

In the 1500s, the plant was known as Absinthium album or Absinthium alpinum, and was used medicinally due to its contents of essential oils and bitter substances.

According to one source, the specific name is derived from the Latin herba (‘herb’) and rota (‘wheel’), alluding to the circular inflorescence. This seems dubious, as almost all composites have circular inflorescences. An alternative interpretation may be that rotta is Italian, meaning ‘broken’ (i.e. finely divided?), perhaps referring to the foliage.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek makros (‘large’) and phyllon (‘leaf’).

The greyish-green leaves are very finely dissected, aromatic, to 10 cm long. Flowerheads are numerous, sometimes up to 50, borne in a flat or slightly domed cluster to 30 cm across. Ray florets are white, much larger than the tiny yellowish or cream-coloured disc florets. The entire flowerhead is only to 8 mm across.

The specific name is derived from the Latin mille (‘a thousand’) and folium (‘leaf’), alluding to the many fine segments of the leaves, in English corrupted to milfoil. Another common name is thousand-weed. In parts of south-western United States, it is called plumajillo (Spanish for ‘little feather’), likewise alluding to the leaves.

The role of this species in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek oxys (‘sharp’) and lobos (‘lobe’), alluding to the sharply pointed lobes on the leaves.

The generic name, applied by French botanist Alexandre Henri Gabriel de Cassini (1781-1832), is derived from Ancient Greek aden (‘gland’) and stylos (‘style’), referring to the glandular styles of the genus.

It may readily be identified by the large, kidney- or heart-shaped, toothed basal leaves, measuring up to 14 cm across and 9 cm in length. Stem leaves are much smaller, eared, gradually getting smaller up the stem. The flowerheads are numerous, densely clustered towards the apex of the stem. They contain only disc florets, to 8 mm long, purplish-blue or pinkish.

The specific name refers to the basal leaves of this plant resembling those of the garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata).

You often come across a growth of common adenostyle, whose leaves have been almost completely eaten by larvae of Oreina cacaliae, a metallic, bluish or greenish beetle, which belongs to the family broad-shouldered leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae). This species is partial to common adenostyle, as well as alpine butterbur (Petasites paradoxus, see below).

It grows in shady montane forests, up to altitudes around 2,200 m, from Spain eastwards across the Alps to the Balkan Peninsula, the Carpathians, and Ukraine, and thence northwards to Poland and Belarus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek apo (‘away from’, i.e. ‘different’) and seris (‘chicory’), referring to the leaves, which slightly resemble the basal leaves of chicory (below).

The specific name, meaning ‘smelly’, alludes to an unpleasant smell from its white, milky sap.

The generic name may be derived from Ancient Greek arni (‘lamb’), alluding to the soft, hairy leaves of these plants. Arnica leaves were formerly utilized as a substitute for tobacco, hence the popular name mountain tobacco.

Arnica has been utilized medicinally for hundreds of years. This subject is discussed in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The specific name is not very appropriate, as the plant also grows in lowlands. Common names include wolf’s bane and leopard’s bane, referring to its great toxicity.

The role of Artemisia species in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry. Mugwort (A. vulgaris) is described on the page Plants: Urban plant life.

It is a shrubby herb, to 45 cm tall, with silvery-white leaves, to 4 cm long, divided into linear segments. Flowerheads are small, yellowish, in arching spikes.

Its distinctive fragrance is due to an essential oil, containing camphor, camphene, eucalyptol, and borneol. In Switzerland and Italy, it has been utilized as an ingredient in vermouth for hundreds of years. Today, it is quite rare due to overcollection.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘star’, alluding to the spreading ray florets.

A number of species are described on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

In former days, a large number of North American composites were included in this genus. However, following comprehensive research, the New World species have been transferred to the genera Almutaster, Canadanthus, Doellingeria, Eucephalus, Eurybia, Ionactis, Oligoneuron, Oreostemma, Sericocarpus, and Symphyotrichum.

It is partial to dry, calcareous soils. In the Alps, it is found from the lowlands up to altitudes around 3,200 m.

It occurs in montane areas of central and southern Europe, mainly in open places or forest clearings, up to elevations around 2,800 m.

The specific name is derived from Bellis, the generic name of the common daisy, and the Latin suffix aster (‘resembling’), referring to the likeness of the flowers to those of the common daisy.

The obsolete specific name michelii was given in honour of Italian botanist Pier Antonio Micheli (1679-1737), professor of botany in Pisa, curator of the Orto Botanico di Firenze, author of Nova plantarum genera iuxta Tournefortii methodum disposita. He was a leading authority on cryptogams (plants reproducing by spores), and discovered the spores of mushrooms.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’) and ophthalmos (‘eye’), presumably referring to the raised disc florets, which, with a bit of imagination, resemble the bulging eyes of bovines.

It is partial to limestone grasslands and dry forests at medium elevations, up to altitudes of at least 2,000 m. It is widely distributed in montane areas of Central Europe and the Balkan Peninsula.

The specific name is derived from the Latin Salix (‘willow’) and folium (‘leaf’), referring to the leaves, which resemble those of certain willow species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for thistle, probably derived from the Sanskrit kasati (‘to scratch’), alluding to the spines.

Many species in this genus are described on the page Plants: Thistles.

The stem is usually to 50 cm tall, sometimes up to 90 cm, slightly arching, branched, smooth or sometimes winged with thorns, upper part mostly without leaves, thorns, and wings. Leaves are very variable, hairless, sessile, blade entire or pinnate, sometimes toothed.

This species differs from other members of the genus in having only a single purplish-red flowerhead, to 3 cm across, at the end of each branch. Initially, it is erect, later often nodding. Involucral bracts are spreading, unlike the rather similar Cirsium tuberosum.

It is partial to rocky limestone areas, from the lower valleys up to altitudes around 3,000 m, distributed from the Pyrenees via the Alps to the northern Balkan Peninsula and the Carpathians.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with removed flowers’, perhaps alluding to each branch having only a single flowerhead.

In the early 19th Century, it was introduced to North America, where it quickly became a nuisance in agricultural areas. It is declared a noxious weed in the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

In colder regions, this plant is a biennial, requiring 2 years to complete a reproductive cycle, overwintering as a rosette. It may grow to about 1.5 m tall, often with branched stems. The leaves are large, often growing to 60 cm long, bipinnately lobed, with a smooth, waxy surface and sharp, yellow-brown or whitish spines at the tips of the lobes. The flowerheads are large, terminal, to 7 cm across, with hundreds of purplish-red disc florets. The flowerhead is surrounded by very large and sharp bracts.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘nodding’, referring to the often nodding flowerheads.

Several pictures, depicting this plant, are shown on the page Plants: Flora in Turkey.

The spines of this plant are rather soft. It has a sturdy stem, varying in height between 40 cm and 1.6 m, widely branched towards the apex, winged, with fine spines along the edge of the ribs. The leaves are all stem leaves, ovate or lanceolate, soft and curly, with fine spines along the margin, the lower ones to 35 cm long and 20 cm wide, gradually getting smaller up the stem.

The flowerheads are densely clustered at the apex of stem and branches, 2-5 together, to 2.5 cm across, disc florets violet-purple, ray florets absent.

The specific name is derived from the Latin personatus (‘masked’), presumably alluding to the very dark bracts.

The flowerhead has several rows of bracts, of which the outer ones are leaf-like with spine-like tips, whereas the inner rows have ray-like, whitish or yellowish bracts, which are hygroscopic. In dry weather they are spread out fan-like, announcing to bees and hover flies that food is available here, whereas in damp weather they fold up to protect the true florets in the centre of the flowerhead. In folklore, this was seen as a sign of forthcoming rain.

The generic name was given in honour of Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria, King of Spain, and Lord of the Netherlands, Karl V (1500-1558), called Charlemagne or Charles the Great. As legend has it, during a plague epidemic, an angel came to him in his dream and told him to use Carlina acaulis (below) to control the feared disease. It was also told that he used the root of the plant to cure disease among his soldiers.

Other members of this genus are described on the page Plants: Thistles.

Divided into 4 subspecies, it is distributed from the Pyrenees eastwards to the Balkans, and thence northwards to Poland and Ukraine. The nominate subspecies is quite common in the Pyrenees.

It is distributed in the major part of central and southern Europe, eastwards to Belarus and Ukraine, with an isolated population in the Caucasus. It grows in dry grasslands, preferably on calcareous soil, from the valleys up to elevations around 2,800 m.

The rhizome contains a number of essential oils and was formerly used as a diuretic and to treat colds. Young buds of the flowerheads can be cooked and eaten, similar to artichokes (Cynara cardunculus), which earned it the nickname hunter’s bread.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘stemless’, composed of a (‘without’) and caulis (‘stem’).

These plants do not have ray florets, but are characterized by most species possessing two types of disc florets, the outer ones much larger, fringed, sterile, acting as attractors to pollinators.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kentauros (‘centaur’), referring to Chiron the Centaur. According to Greek mythology, Chiron once had a festering wound on his foot, made by an arrow dipped in blood of Hydra, a many-headed serpentine monster with a poisonous breath and blood so virulent that even its scent was deadly. Chiron cured himself by dressing the wound with a member of this genus.

These plants have many common names, including centaury, knapweed, starthistle, and cornflower, the latter usually referring to two blue-flowered species, C. montana (below) and C. cyanus, described on the page Plants in folklore and poetry.

This plant, which grows in grasslands and other open areas, is native to highlands of central and southern Europe, from Belgium, France, and Spain eastwards to Poland, the Czech Republic, and Austria, and thence southwards to the Balkan Peninsula, growing at altitudes between 500 and 2,200 m. It is common in the Alps. It is widely cultivated elsewhere and has escaped in many countries, including Denmark, Sweden, Russia, and the United States.

The specific name is not very appropriate, as the plant also grows in lowlands.

The rather similar cornflower (C. cyanus) may be distinguished by having many flowerheads on each branch.

The stem is erect, unbranched, bristly-hairy, to 50 cm tall, leaves many, to 11 cm long and 5 cm wide, lanceolate-triangular, sparsely toothed or entire, hairy, clasping the stem. Flowerheads large, solitary, to 6 cm across, the dark involucre covered in pale, featherlike, stiff hairs. Florets are pink.

The specific name was given in reference to the protruding nerves on the leaves, whereas the prefix plumed refers to the much-divided ray florets.

This plant thrives in drier grasslands, along roads, and in fallow fields, preferably on calcareous soils. It is distributed in almost all of Europe and thence eastwards across the major part of Siberia to Central Asia. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 2,200 m.

The specific name refers to an old belief that the leaves of this plant could treat scabies.

In its first year, this biennial, or sometimes perennial, grows a basal leaf rosette, the following year producing a much-branched, slender stem, erect or ascending, hairy, to 1 m tall. Stem leaves are alternate, to 5 cm long, pinnately divided into very fine segments. Leaves get gradually smaller and less lobed up the stem. Flowerheads are egg-shaped, solitary at the end of stem and branches, to 2.5 cm long and 1.5 cm across, florets pink or purplish-pink, involucral bracts ovate, with a dark tip and fuzzy bristles along the margin. The dark tips lends a spotted appearance to the involucre, which gave rise to one of the English names of the plant.

This species grows in a variety of habitats, including grasslands, fallow fields, pastures, along roads and railroads, and in other disturbed areas. It is native to eastern Europe and south-western Asia, but has become naturalized in numerous other areas, especially in drier areas of North America, where it is considered a serious pest, covering huge areas.

In classical Greek, stoibe was the name of the thorny burnet (Sarcopterium spinosum), a very spiny plant of the rose family (Rosaceae), described on the page Plants: Flora in Turkey. Why it was applied to the spotted knapweed is not clear.

The generic name is Italian, meaning ‘chicory-like’, referring to the likeness of the flowerheads to those of chicory (below).

In Finland, a popular name of this species is ‘bear-hay’, as bears (Ursus arctos) are often observed eating the juicy plant. Moose (Alces alces) and reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) also relish it. The Sami have been known to eat it raw, or boiled in reindeer milk. (Source: luontoportti.com/suomi/en/kukkakasvit/alpine-sowthistle)

In Italy, alpine sow-thistle is also eaten as a vegetable. The young shoots are boiled and served in olive oil or tomato sauce, and the former is sold under the name insalata dell’orso (‘bear salad’). (Source: F. Scartezzini et al. 2012. Domestication of alpine blue-sow-thistle (Cicerbita alpina (L.) Wallr.): six year trial results. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 59(3): 465-471)

The generic name is possibly derived from keksher, a word of Egyptian origin. It is said that chicory was cultivated in Egypt thousands of years ago.

The specific name is a corruption of the word hendibeh, the Arabic name of a near relative, endive (C. endivia).

The role of chicory in folklore is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kirsion. According to Greek physician, pharmacologist, and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (died 90 A.D.), who was the author of De Materia Medica (5 volumes dealing with herbal medicine), this term was used for a kind of thistle, derived from kirsos (‘swollen vein’), alluding to its usage against swollen veins.

These plants were already regarded as being different from the present-day members of the genus Carduus (above) by Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin (see below). He may have noticed that their pappus (seed hairs) form a plume, as opposed to members of Carduus, which have simple, unbranched seed hairs.

Many species in this genus are described on the page Plants: Thistles.

In his outstanding work Pinax theatri botanici (‘Illustrated exposition of plants’), from 1623, this brilliant scientist described about 6,000 plant species, classifying them in a form, which almost equals the binominal nomenclature, introduced by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in 1753.

The major part of the information above is from the website en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaspard_Bauhin.

It is widespread in the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Baltic states and Romania, growing in grasslands with short vegetation, mainly on calcareous soil. In the Alps, it occurs up to elevations around 2,300 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘stemless’, composed of a (‘without’) and caulis (‘stem’).

This plant is widespread in Europe, found from the British Isles, Germany, and Poland southwards to the Mediterranean and Turkey, growing in open habitats, including grasslands, shrubberies, woodlands, and disturbed areas.

The young leaves may be eaten raw, and young stems are also edible after being soaked in water to remove their bitterness. The flower buds can be cooked, similar to artichokes (Cynara cardunculus), and an edible oil is extracted from the seeds.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek erion (‘wool’) and phoros (‘bearing’), alluding to the woolly stem.

It is widespread in southern and eastern Europe, found from the French Massif Central across the Alps eastwards to the Tatra Mountains, the Dinaric Alps, Greece, Ukraine, and European Russia. In the Alps, it is found at altitudes between 400 and 2,000 m.

The specific name, in the form erysithales, was the classical Latin name of an unspecified plant with yellow flowers. The epithet melancholy alludes to the nodding flowerheads, which, apart from the colour, resemble those of the melancholy thistle (below).

It grows in grasslands, shrubberies, open woodland, and along roads and streams. It is native from northern Europe, including Scotland, eastwards across the major part of Siberia to Kazakhstan, Xinjiang, and Mongolia. It also occurs in montane areas of central and southern Europe, and in the Caucasus, and also a few places in Iceland and southern Greenland. In the Alps, it has been encountered up to elevations around 2,400 m.

It was first described by Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin (see genus Cirsium above), as Cirsium maximum, Asphodeli radice (‘the largest thistle with roots like asphodels’), and also as Cirsium montanum, incano folio (‘mountain thistle with grey leaves’).

A Swedish folk name, elgtunga (‘moose tongue’), probably refers to the leaf shape.

Formerly, this species was considered a possible cure for sadness. English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) says that it, being drank in wine “expels superfluous melancholy out of the body and makes a man as merry as a cricket,” adding “Dioscorides [see genus above] saith, the root borne about one doth the like, and removes all diseases of melancholy: Modern writers laugh at him: Let them laugh that win: my opinion is, that it is the best remedy against all melancholy diseases that grows.”

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘like Helenium‘, alluding to the likeness of some leaf forms to those of the basal leaves of elecampane (Inula helenium), which is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Flowerheads are terminal, to 4 cm across, 2-6 densely clustered, surrounded or even sometimes covered by large yellowish bracts. Florets pale yellow, sometimes tinged pink.

The cabbage thistle thrives in wet meadows, along streams, and in humid forests, often forming large stands with the help of underground stems. It is native from western Europe eastwards to western Siberia. In montane areas it is restricted to the lower areas, occasionally found up to altitudes around 2,000 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin holus, genitive holeris (‘vegetable’), alluding to the young stems and leaves being edible. The common name also refers to this usage. In Japan, it is still being cultivated as a vegetable.

It is found in the entire Alps and the northern part of the Balkans, growing in dry, rocky areas at altitudes between 1,100 and 3,100 m.

Previously, young shoots were cooked as spinach or used in soup, and they were also used as pig feed.

A quite similar species, Bertoloni’s thistle (C. bertolonii), is found in the Apennines. It was previously regarded as a subspecies of spiniest thistle.

According to one source, the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek cotyle (‘cavity’, ‘bowl’, or ‘cup’), alluding to the sessile leaves of some members of the genus forming a cavity at the base.

Stem to 90 cm tall, branched above, longitudinally ribbed, sparsely or densely downy-hairy, leaves sessile, ovate or elliptic in outline, to 14 cm long, almost pinnately divided into pointed lobes. Flowerheads are up to 4 cm across, disc florets yellow, ray florets white, to 2 cm long.

The plant was named in honour of Italian botanist Giovanni Battista Trionfetti (1656-1708), also known as Joannes Baptista Triumfetti, curator of the botanical garden of the Sapienza University in Rome. In 1685, he published a paper, Observationes de ortu et vegetatione plantarum cum novarum stirpium historia, in which he attacked a theory, formed by the Italian physician Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694), claiming that a living being was preformed in the seed or egg.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek krepis (‘slipper’ or ‘sandal’), according to some authorities referring to the shape of the fruit.

It is widely distributed in the Jura, the Alps, the Apennines, the Abruzzos, and the Balkans, and is also found in Asia Minor. In the Alps, it grows in meadows and pastures, preferably on acid soil, at altitudes between 1,000 and 2,900 m.

In the Alps, it is regarded as a valuable fodder plant for cattle, hence the Swiss folk names Rombluem (‘cream flower’) and Ankenblüemli (‘small butter flower’).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden’, of course alluding to the flowerheads.

The generic name was used as early as in the 1500s by Swiss physician and naturalist Conrad Gessner (see below) in his work Historia plantarum et vires (1541). It is derived from the Arabic name of these plants, darawnaj or darawnij.

The common name stems from the specific name of D. pardalianches, derived from Ancient Greek pardalis (‘leopard’) and ankhein (‘to strangle’). According to Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.), juice from a Doronicum species was rubbed on meat in the belief that it would cause leopards, which ate it, to die from asphyxiation.

With help from his uncle and his teachers, Conrad was able to attend schools in Zürich, where he studied classical languages. When he was 17 years old, they arranged for him to study theology at universities in France, but due to religious persecution he had to return to Zürich. It was arranged for him to study Hebrew in Strasbourg, and in 1536 he obtained a paid leave of absence to study medicine at the University of Basel.

In 1537, at the age of 21, he published his first book, titled Lexicon Graeco-Latinum, which earned him the professorship of Greek at the newly founded academy of Lausanne. Besides teaching, he devoted himself to scientific studies, especially botany. In 1541, he obtained his doctoral degree, and then returned to Zürich to practice medicine, and to give lectures at the Carolinum (later the University of Zürich). He spent much of his leisure time going on botanical collection trips in the mountains of Switzerland.

His first major work was Bibliotheca (1545), relating the history of bibliography, a catalogue of all the writers who had ever lived, and their works. Historiae animalium, published 1551-58, was a monumental work on animal life, but he only published two botanical works, Historia plantarum et vires (1541) and Catalogus plantarum (1542). While working on a major botanical work, Historia plantarum, he died from the plague, only 49 years old.

The specific name refers to Austria. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

This species grows in humid and often shady areas among limestone rocks, at altitudes from 500 m up to 2,100 m. It is distributed in the eastern Alps and the Carpathians, on the Balkan Peninsula, and in Italy.

The specific name is derived from the Latin columna (‘pillar’), perhaps alluding to the dense, ‘columnar’ growth of the plant.

It is mainly found on eroded mountain slopes in areas of limestone, growing among rubble and gravel. It is native to the Alps, the Pyrenees, and mountains on the Balkan Peninsula and in Corsica, growing at altitudes between 1,400 and 3,400 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with large flowers’, referring to the flowerheads, not the individual flowers. The obsolete specific name is Latin, meaning ‘scorpion-like’, which alludes to the thick, curved rootstock of the plant.

These plants are characterized by their thistle-like appearance, but are easily identified by the spherical flowerhead, which resembles a spiny ball. This inflorescence gave rise to the generic name, derived from Ancient Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’) and ops (‘head’).

It is native from central Europe eastwards to central Siberia, Xinjiang, and Mongolia, southwards to Spain, Turkey, and Turkmenistan, growing in gravelly places up to altitudes around 2,400 m.

The specific name is unexplained.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hierakion, a diminutive of hierax (‘hawk’). According to an ancient legend, hawks were able to hone their eye sight with the milky juice of these plants. Alternatively, the name may refer to the tip of the ray florets, which resemble hawk wings.

It is distributed in mountains of central and southern Europe, from France eastwards to Ukraine, and from Germany and Poland southwards to Italy and the Balkans, growing at altitudes from 1,100 to 2,700 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘hairy’.

The generic name, previously written Hypochoeris, is probably derived from Ancient Greek hypo (‘under’) and choeris (‘young pig’), alluding to the fact that pigs enjoy eating the root of common cat’s-ear (H. radicata). The English name refers to the leaves of this species, which are covered in rough hairs.

This species is partial to meadows and pastures, mainly on siliceous soil, found at altitudes between 1,300 and 2,600 m. It is distributed from the western Alps eastwards to the Balkans, the Carpathians, the Tatra Mountains, and Ukraine.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘one-flowered’, referring to the solitary flowerhead.

The generic name refers to Jacobus, in English called James the Great, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus. He is the patron saint of Spain and, according to tradition, his remains are housed in the city of Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, known as the culmination of the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route.

The name ragwort was given in allusion to the ragged foliage of many members of the genus.

The stem is erect, green or reddish, usually smooth, much branched, sometimes reaching a height of 2 m, but usually lower. The leaves, to 20 cm long and 6 cm wide, are pinnately lobed, the lobes toothed along the margin. The very numerous flowerheads, to 2.5 cm across, have 10-15 yellow, strap-shaped ray florets and many orange disc florets. The flowers are much visited by bees, hover flies, and butterflies.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

Popular names of this species include stinking willie and mare’s fart, alluding to the unpleasant smell of the leaves.

The generic name was the classical Latin name of the garden lettuce (L. sativa), derived from lactis (‘milk’), alluding to the milky sap of this plant.

The stem is to 60 cm tall, erect, branched above, smooth, leaves mostly basal, bluish-green, stalked, pinnate, segments linear to lanceolate, lobed or toothed. Stem leaves gradually get smaller up the stem, less divided and clasping. Flowerheads, to 4 cm across, contain only ray florets, blue or purple, rarely white.

The generic name was applied by Scottish botanist Robert Brown (see below), derived from Ancient Greek leon (‘lion’) and podion (‘small foot’), presumably in allusion to the fuzzy involucral bracts, which somewhat resemble a lion’s paw.

By 1800, Brown was one of the foremost botanists in Ireland, corresponding with a number of established botanists. In 1801, he became a member of an expedition to Madeira, South Africa, and Australia, on board the Investigator, whose captain was British navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders (1774-1814). For three and a half years, Brown studied Australian plants, collecting about 3,400 species, of which about 2,000 were previously unknown to science.

In 1810, he published his results from the expedition in Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen (‘Preliminary Flora of New Holland [today Australia] and van Diemens Island’ [today Tasmania]), the first systematic account of the Australian flora.

The same year, he was appointed librarian of the famous botanist Joseph Banks (1743-1820), and when Banks died in 1820, Brown inherited his library and herbarium, which were transferred to the British Museum in 1827.

In 1830, Brown was one of the founding members of the Royal Geographical Society, and he served as president of the Linnean Society 1849-1853.

It is easily identified by the densely woolly bracts, forming a two-layered star around the flowerhead, which has only 5-6 yellow florets. The stems are very short, usually below 10 cm, occasionally to 20 cm. The spatulate leaves, to 3 cm long and 5 mm wide, are silvery-green, woolly, but much less so than the bracts.

Despite being rather non-descript, this species is one of the most beloved flowers of the Alps and the Balkans, being a national symbol of several countries: Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, Romania, and Bulgaria.

In German, edelweiss means ‘noble white one’, and in the 19th Century it became a symbol of purity. Some even claimed that collecting this plant demanded great courage, which, of course, is pure nonsense, as it grows in alpine meadows and on slopes, and is thus very easy to collect. In his novel Edelweiss, from 1861, German novelist Berthold Auerbach (1812-1882) ridiculously exaggerates this difficulty by claiming that “the possession of one is a proof of unusual daring.”

As time went by, so many plants had been collected that it became rare in many areas. As late as in 1946 and 1947, rangers in the northern part of Tyrol confiscated about 6,400 plants, and in 1959, 288 plants were confiscated in the Ötztal Valley.

Edelweiss was formerly used as a traditional remedy against abdominal and respiratory diseases. In Tyrol, it was boiled in milk and eaten with butter and honey against stomach ache, and it was added to tea to treat tuberculosis, diarrhoea, and dysentery. An ointment of the plant was used against rheumatism and diphtheria.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and anthemon (‘flower’), alluding to the white ray florets of the genus. The disc florets are yellow. Previously, these plants were placed in the genus Chrysanthemum.

This plant, which mostly grows in rocky areas, is distributed in montane areas of central and southern Europe.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘burnt’, presumably referring to the blackish-brown margin of the involucral bracts.

The stem grows to about 1 m tall, basal leaves stalked, up to 25 cm long and 7 cm wide, spatulate to obovate, toothed along the margin, stem leaves sessile, much smaller, to 7.5 cm long, also toothed, base usually deeply lobed or fringed with slender segments. Flowerhead to 7.5 cm across, usually solitary on long terminal stalks. The white ray florets are 15-30 in number, strap-shaped, to 2.4 cm long, apex usually with 3 small teeth. Disc florets yellow, very numerous, sometimes up to 500, forming a slightly domed centre.

Before the introduction of chemical herbicides, it was a troublesome weed in meadows. In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes: “The ox-eye daisy is a beautiful, bad weed. It can and does adorn many a flower garden, but when it climbs over the fence and ambitiously tries to adorn a whole meadow, that is just too much adornment. For after all, a meadow is not a flower garden, and beauty is as beauty does, even among plants. A cow is not sentimental, and daisies in the hay are just that much less hay to her; to her keeper they are just that much less milk.”

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘common’.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek petasos, meaning ’a broad-brimmed hat’, which, like the common name umbrella plant, refers to the large leaves of many species, sometimes growing to 1 m across.

The common name supposedly stems from the habit of using the large leaves to wrap around butter in hot weather, while another popular name, lagwort, refers to the late appearance of the leaves, which do not usually unfold, until the flowers have faded.

The role of these plants in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

It prefers to grow in damp soil in deciduous forests, often at springs or along streams, on mountain pastures, and along roads. It occurs in the major part of Europe, in Turkey, and in the Caucasus. In the Alps, it may be found from the lowlands up to elevations around 2,700 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’, alluding to the white disc florets.

At flowering, between April and June, stems of this plant reach a height of about 30 cm, and when fruiting, they may be up to 60 cm tall. Inflorescences are dense racemes of flowerheads with reddish-white disc florets, ray florets absent. Stem leaves are often reduced to scales. The large basal leaves, which appear after flowering, are triangular or heart-shaped, toothed along the margin, to 30 cm wide, densely covered in snow-white felt beneath.

It is not clear what the specific name refers to.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek prenes (‘drooping’) and anthos (‘flower’), alluding to the pendent flowerheads.

It is partial to shade, growing in forests, in particular on nutritious soil. It is widespread, occurring from western and central Europe and the Balkans, eastwards to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and Turkey. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 2,100 m.

The generic name is derived from the Latin senex (‘old man’), alluding to the white seed hairs of the genus.

This plant is found in rocky areas on calcareous soils in central and southern Europe, growing at elevations between 1,500 and 3,100 m.

The specific name refers to the flowerheads, which resemble those of the genus Doronicum (above).

The stem is erect, to 60 cm tall, hairless or slightly hairy, leaves lanceolate, with numerous small teeth along the margin. Flowerheads are in small, stalked clusters at the apex, each to 3.5 cm across, with 10-16 yellow, strap-shaped ray florets and numerous orange disc florets.

The obsolete specific name was given in honour of French physician and botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) who undertook an expedition to the Middle East 1700-1702, accompanied by German physician and botanist Andreas von Gundelsheimer (c. 1668-1715) and French artist Claude Aubriet (c. 1665-1742).

The generic name is a diminutive of the Latin serratum (‘sawn’), alluding to the serrated leaves of the species below.

This plant may reach a height of 1 m, but is usually lower. The stem is erect, pale-yellowish green, often tinted purplish, smooth, grooved, branched above, lower leaves stalked, to 25 cm long, ovate to lanceolate, varying from entire to almost pinnate, with narrow, pointed lateral lobes and a long elliptic terminal lobe. Upper leaves smaller, short-stalked or sessile. The leaf margin is sharply serrated. Flowerheads are in terminal, branched clusters, each head to 2 cm across, ray florets absent, disc florets numerous, purplish-red or lilac, rarely white or pink.

In former days, it was used medicinally for treatment of ruptures and wounds.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘used for dyeing’, referring to a yellow dye, which was previously extracted from the leaves of this plant. The popular name alludes to the serrated leaves.

The generic name is unexplained. It may be derived from Russian tolpisja (‘a cluster’).

It may grow to 50 cm tall, stem erect, branched above, leaves almost all basal, linear or linear-lanceolate, entire or with a few teeth, narrowed towards the base. The few stem leaves are linear, entire. Flowerheads are solitary at the end of stem and branches, involucre egg-shaped, to 1.1 cm long, bracts brownish-black, mealy, pressed against the involucre. Florets sulfur-yellow. It reproduces vegetatively through underground stems.

The main area of distribution is the Alps, but it also occurs in the French Jura, in Hungary, and on the Balkan Peninsula. It thrives on calcareous soils, often growing in sand or gravel, and among rocks. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to elevations around 2,500 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin staticum (‘remaining’) and folium (‘leaf’). Maybe the leaves remain on the plant for at long time.

Most members of the family are native to temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, with some species in tropical mountains and in the Andes.

Male and female flowers are borne in separate inflorescences, males in pendulous catkins and females mostly in upright spikes. The seed is a nut or, in Betula and Alnus, a winged nutlet.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of alders. Some authorities connect the name with High German elo (’greyish-yellow’), and with Sanskrit aruna (’reddish-yellow’), referring to the fact that the wood of common alder (A. glutinosa), when cut, assumes a bright reddish-brown colour.

The common name evolved from the Old English word for these trees, alor, which is derived from Proto-Germanic aliso.

This deciduous shrub, growing to 6 m tall, has smooth, grey bark, turning blackish with age. The ovate leaves, to 8 cm long and 6 cm wide, are shiny-green on the upperside, pale green beneath, with double-serrated margin. Male catkins are pendulous, to 8 cm long, female catkins mostly erect, ovoid, to 1 cm long and 7 mm wide, in clusters of 3-10 on terminal branchlets. Initially, they are green, turning brown when mature late in the autumn.

The green alder may also reproduce vegetatively by rooting branches that touch the ground.

The specific name is quite odd, meaning ‘alder-birch’.

The origin of the names Myosotis and forget-me-not, and the role of these plants in folklore, is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

The erect stems may grow to 45 cm tall, but are often much lower, sometimes tufted, covered in soft hairs. Basal and lower stem leaves stalked, narrowly oblanceolate or linear, to 8 cm long and 1.2 cm wide, hairy, upper stem leaves sessile, smaller. Inflorescences are scorpoid cymes, to 15 cm long, corolla blue, to 8 mm across, with white throat, encircled by 5 white or yellow scales.

The generic and English names both allude to the former usage of the common lungwort (P. officinalis) to treat lung problems.

This plant is restricted to western Europe, found from the Pyrenees and the western Alps northwards to Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Rhine Province of Germany. It grows in deciduous forests and forest meadows, and along forest edges.

The specific name is not very appropriate, as the plant also grows in lowlands.

Petals are always 4 in number, arranged cross-wise, which has given rise to the alternative family name Cruciferae, derived from the Latin crux (‘cross’) and ferae (‘bearing’). The fruit is a carpel, which, at maturity, splits into two valves, either less than 3 times as long as broad (a silicula), or more than 3 times as long as broad (a siliqua).

Many members of this family are very similar, and ripe fruits are often necessary for identification.

The fruit of these yellow-flowered plants is highly distinctive, being divided into two circular parts, resembling a pair of spectacles.

The generic name is derived from the Latin bi (‘two’) and scutellum, diminutive of scutum (’shield’), referring to the shape of the fruit. In the old days, shields were often circular.

The common name also refers to the fruit, a buckler being a small, round shield, in the past held by a soldier with a handle or strapped to his forearm. The word is derived from Old French (escu) bocler, literally ‘(shield) with a buckle’.

The stem, branched above, grows to about 40 cm tall, leaves lanceolate, coarsely hairy, to 12 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, either entire with a few teeth along the margin, or pinnate. The leaves are gradually smaller up the stem. The yellow flowers are numerous, in loosely branched, terminal racemes, petals narrowly egg-shaped, to 8 mm long. The fruit, divided into two circular parts, is to 5 mm long and 12 mm wide, each part containing a single seed.

The plant sometimes propagates through root shoots.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘smooth’, alluding to the smooth fruits.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kardamon, the name of a kind of cress. The common name bittercress probably refers to the taste of C. amara (below).

It is partial to springs and other damp places, preferably with running water, on nutrient-rich soils. It is native to all of Europe, except Iceland, eastwards to western Siberia, southwards to Turkey and the Caucasus. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to elevations of at least 2,000 m.

The plant is rich in vitamin C, and in former times it was used as a remedy to prevent scurvy.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bitter’.

This species, previously known as Dentaria enneaphyllos, grows in deciduous forests and shrubberies on calcareous soils. It is distributed from southern Scotland and Germany southwards to the Mediterranean, and from central France eastwards to Ukraine and the Crimean Peninsula. In the Alps, it mainly occurs in the valleys.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek ennea (‘nine’) and phyllon (‘leaf’), referring to the 3 leaves each being divided into 3 leaflets, giving the impression that the plant has 9 leaves (see picture below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek drabe, a kind of cress. The popular name whitlow-grass stems from an old belief that members of this genus were able to cure whitlow, i.e. inflammation at the end of a finger or toe.

It grows in gravel and among rocks in calcareous areas, distributed in mountains of southern and central Europe, from the Pyrenees across the Alps to the Carpathians, in the Vosges, the Jura, the Cévennes, the Belgian Ardennes, and on the Gower Peninsula, Wales. In the Alps, it mainly occurs at altitudes between 1,400 and 3,400 m, occasionally encountered down to 400 m.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek aei (‘forever’) and zoion (‘something alive’), thus ‘living forever’, referring to the evergreen foliage.

The generic name is derived from the name Eruca (another genus in Brassicaceae), and the Latin suffix aster (‘resembling’).

The stem grows to 60 cm tall, erect, branched, hairy at the base, leaves pinnate, with 4-8 lobes on each side. Inflorescences many-flowered, terminal, petals yellow, to 9 mm long, the stalked siliquas to 5 cm long.

In classical Latin, Gallicum referred to the lands of the Gauls, who were various tribes, primarily inhabiting what is now France and Belgium. In New Latin, it merely indicated France. The type specimen may have been collected in France.

The natural range of this plant is from the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the northern Balkan Peninsula northwards to northern France and Germany, northwards to central Baden-Württemberg, Franconian Alb, and the Rhine area. It is also found in eastern Europe, eastwards to Ukraine and the European part of Russia, but may be introduced here. In the Alps, it mainly occurs in the foothills, but may be encountered up to elevations around 2,000 m. It is partial to moist, nutrient-rich soils, often colonizing sandy or gravelly banks of lakes and rivers.

It is native to mountains of the Iberian Peninsula, the Pyrenees, and the south-western Alps, growing on arid and rocky slopes at elevations between 1,500 and 2,500 m.

The generic name honours French botanist and teacher Auguste Huguenin (1780-1860), who lived in Savoie. The specific name means ‘with leaves like Tanacetum‘ (tansy, T. vulgare).

The generic name is a Latinized form of thlaspis, the classical Greek term for a kind of cress, possibly derived from thlaein (‘flattened’). The popular name was given in allusion to the flat, circular fruits, shaped like coins.

This species is distributed from eastern France across the Alps to the northern part of the Balkans. It grows on limestone, usually at elevations between 1,600 and 2,800 m, but has been encountered near the peak of the mountain Theodulhorn (3469 m) in southern Switzerland.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with round leaves’.

The family includes lobelias and allies, comprising about 1,200 species previously placed in a separate family, Lobeliaceae, which is now regarded as a subfamily, Lobelioideae, of Campanulaceae.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aden (‘gland’) and phorea (‘to bear’), referring to the nectar glands.

This plant is distributed from central Europe eastwards to central Siberia and the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang and western Mongolia. In central and south-eastern Europe, it occurs in scattered locations, growing in sunny areas along forest margins, in shrubberies, and in grassy areas.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with leaves like lilies’.

The generic name and the popular name, as well as the name of the entire family, were applied in allusion to the bell-shaped flowers of this genus, from the Latin campanula (’little bell’), the ‘bell’ consisting of five fused petals with free tips. This name was first used in 1542 by German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs (see Allium schoenoprasum above).

This species is common throughout the Alps, and also occurs in the Sudetes and the Tatra Mountains, growing in pastures, meadows, and light forest, at altitudes between 600 and 3,000 m. A few small and vulnerable populations are found in southern Norway, possibly relict populations from the latest Ice Age.

In Kärnten, southern Austria, especially skilful reapers and mowers would attach the white-flowered form to their hat as a sign of outstanding efficiency.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bearded’, like the common name alluding to the long hairs along the edge of the petals. In the Italian part of Tyrol, two folknames were braghie del cucu (‘cuckoo’s sock’) and barete de moneghe (‘nun’s cape’), both alluding to the flower shape.

The similarity of its basal leaves to those of the common viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare) caused Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin (see genus Cirsium above) to name it Campanula foliis Echii, floribus villosis (‘small bell with leaves like viper’s bugloss, and with hairy flowers’).

It is restricted to the south-eastern Alps, from the Dolomites to Slovenia, often growing on rocks.

The specific name refers to Carnia, a historical region in the border area between Italy and Slovenia. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

It is mainly found in limestone regions, growing in grassy areas and among gravel. It is distributed from the Pyrenees eastwards across the Alps to the Carpathians and the Balkan Peninsula. It is also found in the French Massif Central and in the Black Forest and the Swabian Alb, southern Germany. In the Alps, it may be encountered up to altitudes around 3,000 m.

Leaves and flowers are edible, raw or cooked, with a pleasant mild flavour.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with leaves like Cochlearia‘ (scurvy-grass). The popular name fairy’s thimble alludes to the small size of the flowers and to their shape.

It grows on calcareous soils in open forests, shrubberies, dry grasslands, and sometimes along roads and trails. It is native to northern temperate areas of Eurasia, from almost all of Europe eastwards to the Pacific, southwards to the Mediterranean, Iran, the Himalaya, northern China, and Japan. It has also become naturalized in North America. In the Alps and the Pyrenees, it usually grows at elevations below 1,500 m, but may occasionally be encountered up to 2,000 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘gathered in a group’, referring to the dense inflorescence. An old folk name is Dane’s blood, alluding to the fancy belief that this plant sprouted in places, where Danish Vikings had been slain in battle.

This species grows in forests and shrubberies, found in almost all of Europe and western Asia, eastwards to western Siberia, Kazakhstan, and the western Himalaya. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 1,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with broad leaves’.

This species grows in open forests, shrubberies, fields, gardens, and along roads, railways, and hedgerows, preferably in partial shade. It spreads by underground rhizomes, often forming dense stands. Even a small piece of rhizome can spout into a new plant, making it very hard to eradicate, once it has entered a garden.

It is found in all of Europe, except Iceland and the British Isles, southwards to the Mediterranean, Turkey, and Iran, eastwards to central Siberia and Central Asia. It has also been introduced to North America, where it has become an extremely invasive weed. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 2,000 m.

The specific name refers to the similarity of this plant to C. rapunculus, whose specific name is a diminutive of the Latin rapa (‘turnip’), thus ‘little turnip’, referring to the shape of the root. C. rapunculus is described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

It is widely distributed in subarctic and temperate areas of Eurasia, from Iceland eastwards to eastern Siberia, southwards to the Mediterranean, the Caucasus, and north-eastern China. It is very common in most parts of Europe, growing mainly on dry, acidic soils. In the Alps, it may be found up to elevations around 1,500 m.

Previously, it was thought that almost similar North American plants were subspecies of the harebell, but they have since been upgraded to separate species, named C. petiolata and C. alaskana.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with round leaves’, alluding to the basal leaves.

English poet William Shakespeare (1564-1616) mentions harebell in his play Cymbeline, in which the main character is the early Celtic king Cunobeline, who ruled in Britain about 9-40 A.D.

It is widely distributed in montane areas of Europe, from northern Spain across the Pyrenees, the Jura, the Black Forest, the Alps, and the Apennines to the Carpathians and the Balkans. In the Alps, it grows at elevations between 1,400 and 3,250 m, whereas in the Black Forest it may be encountered down to 1,000 m.

It was named in honour of Swiss botanist and plant collector Johannes Gaspar Scheuchzer (1684-1738), who specialized in studying grasses.

It grows in montane grasslands and stony areas in the central and southern Alps, the Apennines, the Abruzzo Mountains, and on the Balkan Peninsula, found at altitudes between 400 and 2,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with a spike’.

It is native to the Alps, the souther Juras, the Dinaric Alps, and mountains in the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula, growing at altitudes between 1,000 and 2,900 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling a thyrsus’ – a staff associated with the wine god Dionysus, made from a stem of giant fennel (Ferula communis), entwined with foliage of ivy (Hedera helix). The name refers to the erect, staff-like inflorescence.

In Latin, the term iasione refers to a bindweed (Convolvulus), or a similar plant with a white flower. Why the name was applied to this genus is not clear.

The branched stem is ascending or erect, to 60 cm long, rarely up to 80 cm. The stem leaves are oblong or lanceolate, margin wavy. The upper part of the stem is without leaves. The numerous flowers are gathered in a dense, hemispherical, terminal head, to 2.5 cm across. The inflorescence resembles that of members of the scabious subfamily (Dipsacoideae), of the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae), but differs in the five pale blue petals being fused into a tube at the base. Anthers are white, protruding.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of mountains’. However, this plant is mainly found in lowlands, restricted to the lower part of mountains.

The flowers of this genus are very characteristic, arranged in dense erect panicles, each flower with a narrow, deeply five-lobed corolla, 2 cm or longer, mostly purplish-blue, sometimes pale blue, white, or pink. Initially, the corolla lobes are connected in the upper third, later separated.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phyteuo (‘to plant’), but it was also the name of the rampion mignonette (Reseda phyteuma), whose leaves were cooked as a vegetable.

Stem erect, simple, smooth, to 70 cm tall. Basal leaves long-stalked, blade much longer than broad, pointed, blunt-toothed, basis heart-shaped or rounded. Upper leaves small, linear or narrowly lanceolate, sessile. The inflorescence is a dense, ovate-cylindrical spike of pale blue to violet-blue flowers, to 1.2 cm long, with a long style, which usually ends in three stigmas.

It is a small plant, to 15, sometimes 25 cm tall, branching at the base, often forming dense growths. Stems erect, often dark brown, basal leaves grass-like, linear or spatulate, entire, often bristly, to 2 mm wide. Stem leaves sessile, linear, much shorter than the basal leaves. The hemispherical flowerheads are to 2 cm across, flowers pale to dark blue, back-curved. The hairy style is protruding.

This species is distributed in montane areas of central and southern Europe, found in northern Spain, the Pyrenees, Auvergne, the French Massif Central, the Jura Mountains, the Alps, and the Apennines. It is partial to acid soils, growing at altitudes between 1,500 and 3,600 m, in some areas encountered down to 600 m.