Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Namibia – a desert country

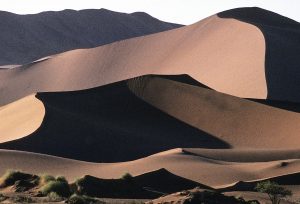

The sun is already low, about to set behind huge, reddish dunes. We park our car and walk towards the dunes, which soon tower above us, the tallest reaching a height of about 275 m. Here and there, a lone acacia tree is testimony to the rain that occasionally falls in this area. Two gemsbok, or southern oryx (Oryx gazella), a large antelope the size of a horse, pass in front of a sand dune. One of them pauses for a long time, gazing intently at us before proceeding after its companion.

Tracks in the sand from beetles, scorpions, snakes, and lizards indicate that other wildlife is also present here. We hear a chuckling sound from the sky, emitted by flocks of pigeon-sized Namaqua sandgrouse (Pterocles namaqua), passing over on their way to a waterhole. The belly feathers of the male are fluffy, making them ideal to suck up a great deal of water while he is drinking. Returning to his chicks, deep in the desert, they are able to quench their thirst in his moist belly feathers.

We trudge up a high dune, following a ridge, created by westerly winds, which blow sand up the dune and over the tip of it, where it whirls around, before gliding down the back side of the dune. The sand is soft, our feet sinking in at every step. Our shadows grow ever longer, while the rays of the setting sun lend an even deeper reddish hue to the dunes – indeed a lovely sight.

The aboriginals of Namibia are the San – small, delicate people with apricot-coloured skin and frizzy ‘peppercorn’ hair. They lived here as hunter-gatherers for thousands of years. The Khoikhoi people arrived in Namibia about 4,000 years ago, and much later, various Bantu tribes migrated from the north and east into the country, bringing with them cattle and implements made of iron. Today, the largest ethnic group is the Ovambo, accounting for around half of the population, and other significant groups are Kavango, Herero, Damara, and Caprivi. The Himba are a distinctive group, living as herders in the Kaokoveld area. Many of them still wear animal skins as clothing, and the women adorn their hair and body with an ochre powder.

The first white settlers were the Boers, who emigrated here from Holland in the 18th Century. They dubbed the San ‘Bushmen’ and the Khoikhoi ‘Hottentots’. The Bantu peoples, as well as the Boers, killed many San and Khoikhoi to get their land, and a number of the survivors were kept as slaves. The remaining San fled into the inhospitable Kalahari Desert, in which they were able to continue their traditional way of living, a few of them still practising this age-old tradition.

In the 19th Century, many Germans emigrated here, and in 1894 Namibia became a German colony. During World War I, the South Africans – who, naturally, were allies of the British – invaded Namibia and expelled the German government. The area became a South African mandate, and independence was not obtained until 1990.

Today, the total population of this vast country is only about 2.5 million. Most are Bantu, only about 200,000 are whites, Khoikhoi, or San. The capital is Windhoek, a relatively small city with about 350,000 inhabitants. Official languages are English, German, and Afrikaans.

Along the coast are scattered breeding colonies of jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus), white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus), and various species of cormorant (Phalacrocorax). The huge sand flats of Walvis Bai (’Whale Bay’ in Afrikaans) is an important feeding area for many birds, especially waders and the greater flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber).

The rocky coast at Cape Cross is home to a large colony of the Cape fur seal (Arctocephalus pusillus), the only breeding seal species in southern Africa. When the females are about to give birth, they come ashore, gathering in huge colonies. The stronger bull seals have already established territories, waiting for the females. Each bull will do his best to gather a harem of females, mating with each of them about a week after they have given birth to a single pup. Six weeks old, the pup leaves the colony, following its mother into the sea, but she will continue to suckle the pup for almost a year. Black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas) and brown hyenas (Hyaena brunnea) often patrol the seal colony to eat dead pups – or to kill one, if its mother is not on the guard.

In this arid desert grows one of the strangest plants in the world, Welwitschia mirabilis – the sole surviving representative of an ancient family of cone-bearing plants, which are distantly related to conifers. In fact, Welwitschia is a tree, but most of its trunk is underground, the roots reaching for water 20 m or more below the desert surface. The black stem above the ground is only 1-1.5 m tall, but more than a metre wide, and flat as a plate. Each plant produces only two large leaves, but they continue growing throughout the life span of the plant, which may be as much as 2,000 years. The long leaves are torn and tattered by the fierce desert winds, giving the impression that there are many more than two leaves. The small flowers are situated between the leaves and the stem. They emit a foul smell, which attracts the flies that pollinate the flowers.

A strange species of lichen, Xanthomaculina convoluta, is found in this desert. It is not attached to stones or trees as most other lichens, but is blown about by the wind, getting nourishments from organic debris and from micro-organisms in the air.

The Namib Desert contains huge deposits of diamonds, especially around the coastal town of Lüderitz. Tourists are not allowed to enter the diamond areas, and numerous signs along the road inform you that trespassers will be fined. In their heyday, many inhabitants of the former diamond towns were immensely rich, spending some of their wealth to construct glorious mansions. Today, most of these towns are deserted and have become ghost towns, some of which are open to the public. It is indeed an eerie feeling to enter the empty houses, half full of sand, doors creaking on rusted hinges.

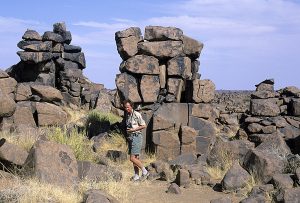

Rocks abound here, often showing fantastic shapes and amazing colours. Near the town of Keetmanshoop is a large area of rocks, which has been dubbed ‘The Devil’s Playground’ due to the weird formations here. Some rocks are balancing on top of other rocks.

The strange quiver tree (Aloidendron dichotomum), which grows to 6 m tall, abounds in this area. It is one out of 7 species of succulent shrubs and trees in the asphodel family (Asphodelaceae), distributed in arid areas of southern Africa, Somalia, and the Arabian Peninsula. These plants were formerly included in the huge genus Aloe, but, following genetic studies, they were moved to a separate genus in 2013. The quiver tree is also known as kokerboom, Afrikaans for ’quiver tree’. Boers who settled in Namibia noticed that the San people used the bark of this tree to make quivers for their hunting arrows.

In the southern part of the country is Fish River Canyon, the deepest canyon in the world, popularly called ‘Africa’s Grand Canyon’. It is slightly deeper than its American cousin, but not as wide, and, therefore, not as impressive.

When the Boers arrived in South Africa, they noticed a species of antelope, which would often jump about, obviously for sheer pleasure. For this reason, they named it springbok (’jumping buck’). Its scientific name is Antidorcas marsupialis, derived from the Greek anti (‘opposite’) and dorcas (‘gazelle’), indicating that this animal is not a true gazelle, and from the Latin marsupium (‘pocket’), alluding to a pocket-like skin flap, which extends from the tail along the midline of the back. Springbok are sometimes seen performing what is called pronking, where an animal, on stiff legs, leaps several times into the air, sometimes as much as 2 m above the ground, with the back bowed and the white tail flap lifted.

Herds of springbok and gemsbok roam the river valleys of the Kalahari, occasionally falling prey to carnivores like lion (Panthera leo) and cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). Among the smaller mammals in this desert, the suricate (Suricata suricatta) is especially conspicuous. This mongoose lives in family groups, and one member of the flock is always standing on its hind legs, keeping a lookout for enemies, such as eagles, kites, or jackals, while the rest of the group is searching for food like beetles, lizards, scorpions, and other small animals. Spotting an enemy, the sentry emits a shrill call, causing all members of the flock to rush for shelter. Other common species among the smaller mammals are yellow mongoose (Cynictis penicillata) and Cape ground squirrel (Xerus inauris).

Until about fifty years ago, bands of San people were roaming this desert as hunter-gatherers, collecting roots of wild plants and hunting game such as springbok, gemsbok, and southern giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis ssp. giraffa). Today, most of the Kalahari has been made into a national park, and the San people have been forced to settle in villages. In Botswana, a few have been able to practice their age-old traditional way of life.

A multitude of animals roam the grassland and the scrub forest around the pan, including springbok, lion, elephant (Loxodonta africana), Burchell’s zebra (Equus quagga ssp. burchelli), blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. taurinus), and greater kudu (Strepsiceros zambeziensis).

The plains zebra in Namibia was previously regarded as a distinct subspecies, antiquorum. However, recent studies have revealed that it is similar to Burchell’s zebra, subspecies burchelli, which was once considered extinct. As subspecies burchelli was described prior to antiquorum, the former name takes precedence. Thus, the plains zebras of Namibia are now called Equus quagga ssp. burchelli. Following the extermination of the quagga, ssp. quagga, in the late 1800s, Burchell’s zebra is now the least striped surviving subspecies.

Until recently, the greater kudu was called Tragelaphus strepsiceros. This species was widely distributed in eastern and southern Africa, divided into three subspecies: Cape, or Zambezi, greater kudu, ssp. strepsiceros, which was found from southern Kenya southwards through eastern Africa to South Africa, and thence westwards to southern Angola and Namibia; northern greater kudu, ssp. chora, which was distributed from Eritrea southwards to northern Kenya; and western greater kudu, ssp. cottoni, living in southern Chad and Sudan, and northern Central African Republic and South Sudan.

However, recent genetic research has caused the greater kudu to be placed in a separate genus, called Strepsiceros strepsiceros, with four subspecies: strepsiceros, which is restricted to southernmost South Africa, zambeziensis, which occupies the remaining area of the former strepsiceros, and finally chora and cottoni. Some authorities have upgraded these subspecies to full species.

Male kudus have impressive spiralled horns, and for this reason they have been much persecuted by trophy hunters.

Etosha is home to a small population of 60-80 blue cranes (Anthropoides paradisea), hundreds of kilometres away from their normal range in South Africa. Incidentally, this small, bluish-grey crane is the national bird of South Africa.

Various birds, including red-shouldered glossy-starling (Lamprotornis nitens) and southern yellow-billed hornbill (Tockus leucomelas), have become remarkably confiding in the park campsites, searching the ground – and sometimes tables – for titbits.