Chinese minorities

This Yi woman, clad in traditional dress, is counting her money at a market in the town of Yuanyang, Yunnan Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wearing traditional dress, this elderly Nakhi woman is performing a dance, Lijiang, Yunnan Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Tibetan woman, clad in traditional dress, Shigatse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

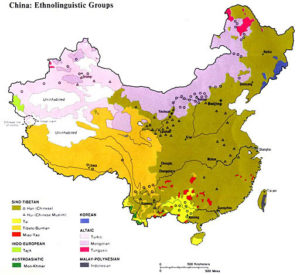

Officially, the Chinese government recognizes 55 ethnic minority groups within Chinese territories, comprising c. 8.5% of the population, the others being Han Chinese. The largest minority groups are the Zhuang (18 million), Manchu (15 million), Hui (10 million), Miao (9 million), Uyghur (8 million), Tujia (8 million), Yi (7.8 million), Mongols (5.8 million), Tibetans (5.4 million), Buyei (3 million), Yao (3 million), and Koreans (2.5 million).

Some ethnic minority groups of Taiwan are presented on the pages Portraits, and People: Children around the world, and examples of their artwork are shown on the page Culture: Tribal art of Taiwan.

Linguistic groups of China. (Map borrowed from worldstatesmen.org/China.html)

Bai

The Bai, numbering about 2 million, originated as a distinct people about 2,000 years ago. The majority live in an area around the great Er Hai Lake, near the city of Dali, Yunnan Province. Some also live in the Bijie area of Guizhou, and the Sangzhi area of Hunan. The fertile lands in the Dali area yield plenty of crops, and the Bai are a relatively wealthy and prosperous people. They also have income from natural resources, such as marble, and they are famed for being skillful traders, silver smiths, and carpenters. On Lake Er Hai, some fishermen still practice fishing with tamed cormorants. Pictures, depicting this practice, may be seen on the pages Boats, and Fishing.

The religion of the Bai is Benzhu, in which multiple gods are worshipped. Some Bai have converted to Buddhism, Daoism, or Christianity, all described on the page Religion.

The colour white is held in high esteem among the Bai. These girls in Dali, dressed in the local costume, are posing for tourists. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bai women, shopping at a market near Er Hai Lake. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Bai woman is on her way home with goods, north of Dali. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bai farmer, north of Dali. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bai man, carrying his daughter in a basket, Xizhou, Yunnan Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dai

The term Dai covers several distinct cultural and linguistic groups, and various dialects of the Dai language group are spoken from the Shanxi Province of China southwards to Southeast Asia and north-eastern India. They number about 1.2 million in China, 6.3 million in Myanmar, 150,000 in Thailand, and 130,000 in Laos.

Some Dai people follow their traditional religion, whereas others are among the few people in China to practice the Theravada (Hinayana) school of Buddhism.

This Dai woman, clad in traditional dress, is selling vegetables at a market in the town of Yuanyang, Yunnan Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dai woman, visiting the market in Yuanyang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hani

Today, more than 90% of the Hani people, who number about 1.2 million, live in the Yunnan Province, whereas the rest live in Laos (where they are known as Ho) and Vietnam.

Traditional head ornament of a Hani woman, Yuanyang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Khampas

From old times, the indigenous people of the Kham region, the Khampas, were renowned for their marksmanship and horsemanship. They played a major role in an uprising against the Chinese communists, who invaded Kham in 1950.

Following the downfall of the local government in 1954, Kham was divided between the Tibetan Autonomous Region and Sichuan, and smaller areas in Gansu and Yunnan.

When the Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959, the Khampas revolted, forming a guerilla movement, which fought against the Chinese army, backed by the United States, who supplied them with weapons and trained them in guerilla warfare.

Guerilla camps were established in the Nepalese kingdom of Mustang, with the consent of the king, from where the guerillas raided Chinese army camps in nearby areas of Tibet. However, even for these hardy people, life was very tough, and, reluctantly, most of them ended their resistance around 1969.

Khampa man in Shigatse. Men of this tribe often adorn their long hair with red cloth. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In 1987, these Khampas were working as porters in the town of Khasa, on the Nepalese border. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Miao

The Miao are one of the largest Chinese ethnic groups, numbering about 11 million, of which 9 million live in southern China, primarily in montane areas of the provinces of Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan. Some sub-groups of the Miao, most notably the Hmong people, have migrated to Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Following the communist takeover of Laos in 1975, a large group of Hmong refugees resettled in the West, mainly in the United States, France, and Australia.

Miao village, Guizhou Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Maize cobs, drying outside a Miao house, Guizhou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nakhi

The Nakhi, also called Nashi or Naxi, are a small minority, counting about 300,000. They mainly live in their political and commercial centre in the city of Lijiang, and around their religious centres at Sanba and the calcium bicarbonate terraces at Baishueitai.

Since Lijiang was founded during the reign of Mongolian emperor Kublai Khan, in the 13th Century, the Nakhi have managed to benefit from the fertile land around Lijiang. This city had a strategic location between areas, which were traditionally dominated by Chinese and Tibetans, and the Nakhi have obtained great influence due to this location. Also, the city was situated on a major trading route between China, Tibet, and India.

Today, Lijiang is a delightful place, with many canals, lined with weeping willows, meandering through the old city, which has preserved a large number of old-style wooden houses, and many arched bridges, which span the canals.

The Nakhi religion, called Dongba, is based on the relationship between nature and man, who, according to Dongba mythology, are half-brothers. Nature is controlled by spirits, called Shu, who are often depicted as part human, part serpent. Dongba shamans perform rituals, called Shu Gu, to appease these spirits and prevent them from causing earthquakes, droughts, and other natural disasters.

A widely practiced Dongba ritual is Zerq Ciul Zhuaq (literally ‘repaying the debts to a tree’), which is performed by a shaman, if a person falls ill or has bad luck. In many cases, the performed ritual reveals that the person in question has cut down a tree, or has been washing dirty items in the forest. The shaman then performs a ritual at the position of the bad activity, apologizing to the nature god Shu.

The traditional New Year of the Nakhi falls on the first day of the second lunar month. At this time, a most important festival takes place, when the Nakhi, dressed in their best finery, gather at the Baishueitai Terraces to pay respect to the gods of nature.

The word Dongba is also used about the pictorial alphabet, which is the core of the Nakhi literary heritage. This alphabet, which is directly attached to the ancient Dongba belief, is one of the few examples of a pictorial script, which is still in usage today. It is only practiced by the shamans.

The eccentric Austrian-born American botanist and explorer Joseph Rock (1884-1962), who lived in Lijiang 1921-1949, spent many years producing a dictionary of the Dongba characters and their meaning. He also went on numerous expeditions to remote corners of Yunnan with the aim of describing these areas, and to collect plants.

In 1985, British author Bruce Chatwin (1940-1989) followed in Rock’s footsteps, intrigued by the man and delighted by his writing. Here is one of Chatwin’s quotes of Rock’s unusual prose:

“A short distance beyond, at a tiny temple, the trail ascends the red hills covered with oaks, pines, Pinus Armandi, P. yunnanensis, Alnus, Castanopsis Delavayi, rhododendrons, roses, Berberis, etc., up over a limestone mountain through oak forests to a pass with a few houses, called Ch’ou-shui-ching (‘Stinking water well’). At this place, many hold ups and murders were committed by the bandit hordes of Chang Chichpa. He strung up his victims by the thumbs to the branches of high trees and tied rocks to their feet, lighting a fire beneath, he left them to their fate. It was always a dreaded pass for caravans. At the summit, there are large groves of oaks (Quercus Delavayi).”

The political and commercial centre of the Nakhi people is the delightful city of Lijiang. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Clad in traditional dresses, these Nakhi women are performing a dance, Lijiang. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nakhi pagoda, south of Lijiang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nakhi women, shopping at a market in the town of Xizhou. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nakhi Dongba (shaman) at a shrine, a crack in the sacred calcium bicarbonate terraces at Baishueitai. This crack resembles a vagina, and a lump above it symbolizes the pubic hairs. Incense sticks have been stuck into a tuft of grass beneath the crack. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

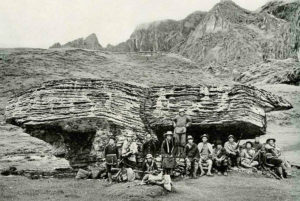

Joseph Rock and staff at Konkaling, 1928. He called this upper watershed The Kingdom of Muli, and the king of Muli provided him and his staff the necessary protection against the ubiquitous bandits of the area, which meant that they could get out alive. (Photo: Public domain)

Shuei

The Shuei (also written Shui or Sui), numbering about 450,000 persons, are descended from the ancient Baiyue peoples, who inhabited southern China, even before the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.). The name Shuei (‘water’ in Chinese) was adopted during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Today, the vast majority of the Shuei live in Guizhou Province, mainly in the Sandu Shui region. Some live in the Yunnan Province, and a few hundred in bordering areas of Vietnam.

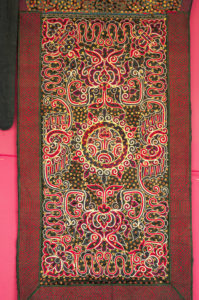

The Shuei are renowned for their folk arts, including paper-cutting, stone-carving, silver jewelry making, and batik dyeing. They have a unique local calendar, which basically follows the Chinese lunar calendar.

The Shuei are renowned for their arts. This woman, clad in traditional dress, is twisting horsetail hairs into thread, Guizhou Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shuei woman, carrying her child in a traditional woven backpack, Guizhou. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

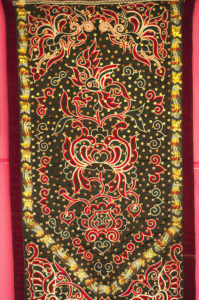

Designs on traditional Shuei backpacks, Guizhou. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetans

The Tibetan Empire arose in the 7th Century, but soon disintegrated into several more or less independent territories. The major part of western and central Tibet, named Ü-Tsang, was periodically unified under various Tibetan governments, residing mainly in Lhasa and Shigatse. The eastern parts of Tibet, called Kham and Amdo, were more or less independent, ruled by local tribal groups.

Following the Xinhai Revolution against the Qing Dynasty in 1912, Chinese soldiers were expelled from Ü-Tsang, which was declared an independent state in 1913, which, however, was not recognized by the subsequent Chinese Republican government. Tibet maintained its independence until 1951. Following the Battle of Chamdo in 1950, the Chinese communists incorporated Kham and Amdo into the provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai, and a year later, Tibet proper was declared an autonomous region within the People’s Republic of China. Following a failed uprising in 1959, the previous Tibetan government, including their religious leader, the Dalai Lama, fled to India.

The current population of Tibetans is estimated at about 6.5 million. Outside the Tibet Autonomous Region, significant numbers of Tibetans live in the Chinese provinces of Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan, as well as in India, Nepal, Bhutan, Switzerland, and the United States.

Most Tibetans practice Mahayana Buddhism, or Lamaism, although some still observe the ancient animist Bon religion. You may read about the Mahayana Buddhism on the page Religion: Buddhism, whereas the Bon belief is described on the page Religion: Animism.

Tibetans, and the Chinese invasion of Tibet, are dealt with in detail on the page Travel episodes – Tibet 1987: Tibetan summer.

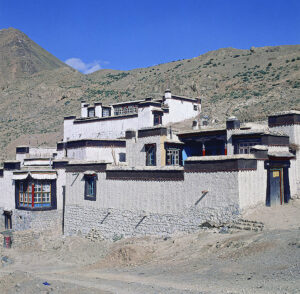

Various street scenes in the city of Shigatse, 1987. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetan boy, Shigatse. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

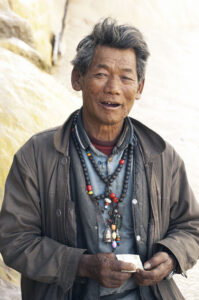

When I photographed this elderly man in Shigatse, he cracked down laughing and invited me into his house. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elderly pilgrim outside the Palcho Monastery in the town of Gyantse. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These Tibetan women, who pay a visit to the Tashilhunpo Gompa, Shigatse, are wearing traditional dress and old-fashioned felt shoes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young Tibetan mother in Lhasa is transporting her child in a traditional backpack for babies. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetan legs, wearing a hat and traditional felt shoes, Shigatse. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yao

Yao is a term, which covers various minorities in China and Vietnam. They mainly reside in mountainous areas of southern and south-western China and northern Vietnam. There are almost 3 million Yao in China and roughly 500,000 in Vietnam.

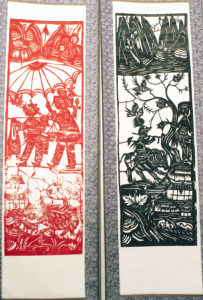

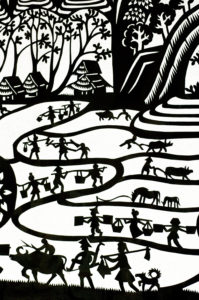

Yao people, producing paper cuttings, Duyun, Guizhou Province. Note the fancy headdress of the woman, made from a folded-up towel. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yi

The Yi people (pronounced ‘eeh’, short), also called Nuosuo, and formerly Lolo, comprise more than 9 million, of whom over 4.5 million live in the Yunnan Province, c. 2.5 million in southern Sichuan, and about 1 million in north-western Guizhou. Formerly, the Yi were semi-nomads, living in the lower parts of the Tibetan Plateau, from where they often went plundering in the lowland agricultural areas.

During the communist Long March in the 1940s, the Yi supported the rebels, but they were far from happy, when the communists returned with their many doctrines. A prolonged guerilla war ensued, and relations between the Yi and the central government are still somewhat strained. Today, most Yi are farmers.

The Yi have a written language, dating back from the 13th Century. Their animistic religion is called Bimoism, and the shamans are known as bimo, meaning ‘master of scriptures’. The Yi worship their ancestors, besides local gods of nature, such as fire, hills, trees, rocks, water, earth, sky, and wind.

Yi house in a village near Weining, Guizhou Province. Maize foliage is stacked outside, to be used as fodder. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Yi woman in traditional dress, Yuanyang, Yunnan Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yi boys, playing with a wheelbarrow, near Weining, Guizhou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a rainy day, I paid a visit to a market in the town of Yuanyang, Yunnan Province. The following pictures are impressions of Yi people from this market.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded April 2020)

(Latest update October 2022)