Calidris sandpipers

Red knot (Calidris canutus) in breeding plumage, photographed during its north-bound migration, Delaware Bay, New Jersey, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Purple sandpiper (Calidris maritima) in breeding plumage, Rauðanupur, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding sanderlings (Calidris alba) in winter plumage, Pan de Azucar National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male spoon-billed sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea) in breeding plumage, photographed in its territory, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Swimming ruffs (Calidris pugnax) in winter plumage, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sandpiper is a term used for several genera of waders, including Tringa, Actitis, Bartramia, Prosobonia, Xenus, and Calidris. On this page, several members of the latter are presented.

Today, there are 24 species of smallish to very small waders in the genus Calidris. Previously, it contained fewer species, but several birds, which were previously placed in other genera, have been moved to this genus, including spoon-billed sandpiper (C. pygmaea) and ruff (C. pugnax).

The major part of these birds breed in Arctic areas, a few also in sub-Arctic and northern temperate regions. They spend the winter on shores and in inland wetlands in temperate, subtropical, and tropical regions around the world.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalidris, a term used by Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) for some grey-coloured water bird. The English term for the smallest members of the genus is stint, of unknown origin. It may stem from the call of the little stint (Calidris minuta), a sharp stit.

I would like to thank Danish artist Jens Gregersen for permission to quote text and use pictures from his splendid book Arktisk sommer (‘Arctic Summer’), first published in 2014.

Powerful performance

Calidris sandpipers are very fascinating. The northernmost species live a precarious life which seems almost impossible. The summers in this region are very short, and it is make or break, whether they succeed in bringing up their young. A longer period of bad weather may cause the major part of the chicks to perish.

A number of studies in later years have revealed that the females of some species often lay two clutches after arriving at the breeding site, one for the male and one for herself, or sometimes for two different males! When you consider that each clutch weighs almost as much as the bird itself, it is indeed a powerful performance.

The sharp-tailed sandpiper (C. acuminata) breeds in central and eastern Siberia, spending the winter in Australia and New Zealand. In his book Arktisk sommer, Jens Gregersen says: “Lately, scientists have discovered that immature birds perform a strange, irrational migration, going to the Yukon Delta in Alaska, i.e. due east. When you consider that the sharp-tailed sandpiper breeds in the region between the Lena and Kolyma Rivers, it adds up to between 2,000 and 4,000 km in the wrong direction. When they arrive here they are indeed scrawny. They now spend some time here, and the abundant food soon brings them into shape again. Some time in autumn, they continue to Australia, without stopping on the way! This adds up to about 10,000 km, but the sharp-tailed sandpiper has long and strong wings. Their parents took the direct route south through Mongolia and China via Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and New Guinea to Australia, making many stops on the way. Some time in the winter they are united with their young, which made the long detour via Alaska.”

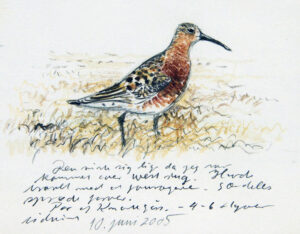

Sharp-tailed sandpiper at its nest, Kolyma River, Siberia. (Illustration from Jens Gregersen’s book Arktisk sommer, with permission)

Calidris alba Sanderling

This small bird is a circumpolar breeder, encountered in High Arctic wetlands in Greenland, Svalbard, northern Taymyr Peninsula, Severnaya Zemlya, the Lena Delta, New Siberian Islands, northern Alaska (rare), and the Canadian Arctic islands, from Banks to Ellesmere and southwards to Southampton.

It spends the winter along shores in temperate, subtropical, and tropical areas, as far south as southern South America, South Africa, and Australia.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’, referring to its white winter plumage. The popular name is derived from Old English sand-yrðling (‘sand-ploughman’), referring to its feeding habit, running along sandy shores while constantly sinking its bill into the sand in search of food.

Sanderlings in winter plumage, resting on coastal rocks together with a single grey gull (Leucophaeus modestus), Pan de Azucar National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding sanderlings in winter plumage, Pan de Azucar National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sanderlings in winter plumage, feeding on a beach, Border State Park, south of San Diego, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A single sanderling in transitional plumage, feeding on eggs of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus), together with red knots (Calidris canutus) and ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres), Delaware Bay, New Jersey, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sanderling at its nest, Zackenberg, eastern Greenland. (Illustration from Jens Gregersen’s book Arktisk sommer, with permission)

Calidris alpina Dunlin

A very widespread bird with a circumpolar distribution, divided into 10 subspecies. It breeds in Arctic, sub-Arctic and northern temperate regions, southwards to southern Alaska, Hudson Bay, Iceland, the British Isles, northern Germany, Poland, and the Baltic States, but is absent from southern Siberia and Central Asia. In later years, most European populations have declined drastically due to draining of suitable habitats.

The specific name refers to mountains of Lapland, from where Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), when he described the bird in 1758, had obtained a specimen. The common name stems from Old English dunling, first recorded around 1530. It is derived from dun (‘dull brown’), with the suffix -ling, meaning a person or another being.

Subspecies schinzii breeds in south-eastern Greenland, Iceland, the southern British Isles, southern Scandinavia, and the Baltic States. These birds in breeding plumage were encountered at Silalækur, Aðaldal, northern Iceland (top), and at Nissum Fjord, western Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subspecies sakhalina is distributed from north-eastern Russia eastwards across a vast area to Chukotka, eastern Siberia. – Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding and resting dunlin, subspecies sakhalina, near Anadyr Airport, Chukotka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During their southbound migration, these dunlins in transitional plumage are feeding and resting, Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris bairdii Baird’s sandpiper

This small bird breeds in the northern tundra, from far north-eastern Siberia (Wrangel Island and the Chukotka Peninsula) eastwards through Alaska and northern Canada to north-western Greenland. It spends the winter in South America.

The specific name commemorates Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823-1887), who worked as naturalist and assistant secretary in the Smithsonian Institution.

Baird’s sandpiper, Laguna de Chaxas, Salar de Atacama, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris canutus Red knot

Following a battle in England in 1016 between troops, led by the English prince Edmund, and Vikings, led by the Danish prince Knud (995-1035), son of King Svend Forkbeard, Knud was crowned as King of England. In 1018, he also became King of Denmark, and in 1028 King of Norway.

According to legend, Cnut the Great, or Canute, as he was called in England, regarded a certain species of wader, suitably fattened with white bread and milk, as a delicacy. This bird was since known as knot, named after the king. Obviously, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) knew this legend, because when he described the bird in 1758, he named it Tringa canutus. Today, it is called red knot to distinguish it from the great knot (C. tenuirostris, see below).

Divided into 6 subspecies, the red knot breeds in the far northern tundra in Alaska, north-eastern Canada, Greenland, and central and eastern Siberia. In autumn, it migrates to western Europe, Africa, Florida, Central America, southern South America, Australia, and New Zealand. A few spend the winter in the Mediterranean and in southern India.

When the birds arrive on their breeding grounds in the tundra, very little food is available, so they literally starve. They must depend on fattening up before arriving. On its north-bound migration, birds of the subspecies rufa, which breed on the Arctic Canadian islands, make a stopover in Delaware Bay, New Jersey, to feed on the nutritious eggs of the Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus), thousands of which gather here in May to lay eggs. This coincides with the arrival of up to one million waders, primarily red knots, turnstones (Arenaria interpres), semi-palmated sandpipers (Calidris pusilla), and sanderlings (Calidris alba).

It has been estimated that each spring birds and fish consume about 320 tonnes of horseshoe crab eggs on American shores. More about this fascinating animal is presented on the page Animals – Reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates: Horseshoe crabs – living fossils in peril.

Red knots, subspecies rufa, and ruddy turnstones (Arenaria interpres), roosting on a beach during high tide, Delaware Bay, New Jersey, United States. In the background laughing gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla) and American herring gulls (Larus smithsonianus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red knots and ruddy turnstones, feeding on eggs of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus), Delaware Bay. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red knot, subspecies islandica, incubating among Arctic bell-heather (Cassiope tetragona) and mountain-avens (Dryas octopetala), Zackenberg, eastern Greenland. (Illustration from Jens Gregersen’s book Arktisk sommer, with permission)

Calidris ferruginea Curlew sandpiper

This numerous wader breeds in the Siberian tundra, from the Yamal and Taimyr Peninsulas eastwards to the Chukotka Peninsula, and on the New Siberian Islands. It winters mainly in Africa, and in some numbers in southern Asia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and Australia.

During surveys of waders and other water birds along the coast of Tanzania in 1988 and 1989, we counted about 21,000 curlew sandpipers, corresponding to about 86 birds per km. Our ‘guesstimate’ was that around 100,000 individuals of this species winter along the Tanzanian coast. (Source: Petersen, I.K., T. Bregnballe, K. Halberg & O. Thorup 1989. Tanzania Wader Survey. A preliminary report of the Danish-Tanzanian ICBP-expedition 1988. Copenhagen University)

The specific name is derived from the Latin ferrugo (‘iron rust’), from ferrum (‘iron’), given in allusion to its rusty-red breast in the breeding plumage. The common name refers to its down-curved bill, slightly reminiscent of the bill of the curlew (Numenius arquata).

A huge flock of curlew sandpipers, together with 4 crab plovers (Dromas ardeola), 2 grey plovers (Pluvialis squatarola), and a few Mongolian plovers (Charadrius mongolicus), Msimbazi Beach, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Curlew sandpipers, a few Mongolian plovers (Charadrius mongolicus), and a single sanderling (Calidris alba, the small white bird), Msimbazi Beach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows 2 curlew sandpipers (in front, centre), many greater sand plovers (Charadrius leschenaultii), 2 Terek sandpipers (Xenus cinereus, with yellow legs), and a single sanderling (Calidris alba, the white bird to the right), roosting on a sandbar during high tide, Msimbazi Beach. A sooty gull (Ichthyaetus hemprichii) and crab plovers (Dromas ardeola) are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During high tide, these curlew sandpipers are roosting in mangrove trees, Kirongwe, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Curlew sandpipers, moulting into breeding plumage, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Curlew sandpiper in breeding plumage, Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia. (Illustration from Jens Gregersen’s book Arktisk sommer, with permission)

These feeding curlew sandpipers, observed in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark, have just begun moulting into winter plumage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris maritima Purple sandpiper

This bird breeds in Arctic mountains in northern Canada, from Banks Island southwards to Ellesmere and Baffin Islands, in Greenland, Iceland, Jan Mayen, Bear Island, Svalbard, along the Scandinavian mountain range, northern Norway, extreme north-western Russia, Franz Josef Land, Novaya and Severnaya Zemlya, and on the Taimyr Peninsula.

It spends the winter months along shores of north-western and western Europe, southwards to Portugal, in extreme southern Greenland, and along the North American Atlantic Coast, southwards to South Carolina.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living at the sea’, derived from mare (‘sea’). In winter, the bird is usually observed along coasts.

Purple sandpiper in breeding plumage, Rauðanupur, northern Iceland. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

From a distance, this incubating purple sandpiper is almost impossible to spot among the withered grass on Selvogsheiði Moor, southern Iceland. I only found the nest, because I observed the bird from my car, when it relieved its incubating mate. When I stepped out of the car to have a closer look, the bird flashed the pale underside of its wings to lure me away from the nest. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chick of purple sandpiper, a few days old, Rauðanupur, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris mauri Western sandpiper

In the breeding season, this species is essentially restricted to the tundra in Alaska, where it is abundant, especially in the Yukon Delta. Small and unstable breeding populations also occur in Chukotka, eastern Siberia, and on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea.

In autumn, it migrates to the Pacific and Atlantic shores, from extreme south-western Canada and New Jersey southwards through the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America to northern and western South America.

The specific name was given in honour of Italian botanist Ernesto Mauri (1791-1836), director of the botanical garden in Rome.

Feeding male western sandpiper, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male western sandpiper in courtship display, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris minuta Little stint

An abundant wader, with an estimated world population of between 1 and 1.5 million. It breeds in the Siberian tundra, between the rivers Pechora and Kolyma, and there is also an isolated population in far northern Norway and extreme north-western Russia.

It winters mainly in Africa, with some numbers around the Mediterranean, and from the Middle East along the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula to the Indian Subcontinent.

In Latin, the specific name means ‘very small’.

Little stint, moulting into breeding plumage, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Little stint with young, Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia. (Illustration from Jens Gregersen’s book Arktisk sommer, with permission)

Calidris minutilla Least sandpiper

This tiny bird, the smallest of all shorebirds, breeds in Arctic tundra and taiga in Alaska and Canada, from Yukon to northern British Columbia eastwards to Labrador and Nova Scotia, and also on the eastern Aleutian Islands.

It spends the winter from southern United States southwards through Mexico and the Caribbean to Peru and northern Brazil.

The specific name is derived from the Latin minutus (‘very small’), and the suffix illa, which denotes something small, thus the name may be translated as ‘very small indeed’.

Least sandpipers, feeding together with short-billed dowitchers (Limnodromus griseus), Salton Sea, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Least sandpipers, feeding on alkali flies (Ephydra hians), Lake Mono, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris pugnax Ruff and reeve

This peculiar species, where the male is called ruff, the female reeve, is unique among waders in that the male in breeding plumage has a huge ruff of feathers around the neck.

When the breeding season begins, the males gather on an arena on a grassy spot, a so-called lek. When a female arrives at the arena, the males start fighting (in deep silence) to attract the attention of the female. She walks around to survey the entire group before choosing a male, which will mate with her. She then leaves to take care of nest-building, incubating, and chick-rearing by herself.

As a breeding bird, this species is widely distributed in Arctic, sub-Arctic, and northern temperate areas, from eastern England across northern Europe and Siberia, eastwards to around the Kolyma River. There are also scattered populations in Central Asia.

European populations have declined drastically in later years due to draining and overgrowth of suitable habitats.

The wintering area includes southern and western Europe, Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, southern Asia, and to some degree Australia.

Formerly, this species was named Philomachus pugnax, but genetic research has shown that it is closely related to Calidris sandpipers. The former generic name is derived from the Greek philos (‘loving’) and makhomai (‘to fight’), whereas the specific name is derived from the Latin pugno (‘I fight’) and ax (‘inclined to’).

Ruffs on the lek, awaiting the arrival of females, Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When the reeves arrive, there is great activity among the ruffs, Tipperne. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Reeves wander around to choose the male they want to mate with, Tipperne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ruff and reeve mating, Tipperne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nest of reeve, Nature Reserve Klægbanken, Ringkøbing Fjord. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ruff in winter plumage, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bathing ruff, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These ruffs and reeves are resting an unusual place: a stone platform near the sacred lake of Pushkar, Rajasthan, India. Some of the ruffs are in partial breeding plumage, displaying a bit of a ruff. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris pygmaea Spoon-billed sandpiper

This small wader resembles several species of stints, but at close quarters its peculiar bill, shaped like a broad spade, is revealed. Due to the bill, some taxonomists place the bird in a separate genus, Eurynorhynchus.

In the breeding season, it is restricted to Arctic and sub-Arctic tundra along coasts of north-eastern Siberia, from Chukotka southwards to the northern part of Kamchatka. It has declined alarmingly in later years, mainly due to destruction of many of its feeding areas in China, on which it is dependent on its way to the wintering areas in southern China, Indochina, and to some degree eastern India. These feeding areas have been converted into salt pans, shrimp farms, and rice fields.

Today, the world population numbers maybe fewer than 100 breeding pairs, and it is feared that it will become extinct in the wild within a few decades. A captive population exists in Slimbridge Wetland Wildlife Reserve, Gloucestershire, England.

Male spoon-billed sandpiper in breeding plumage, photographed in its territory, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. In 2011, when I visited this sandspit together with Jens Gregersen and Max Nitschke, there was a single pair, possibly 2, in this area. Other years, up to 4 pairs have been found here. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris ruficollis Red-necked stint

This small stint is a common breeding bird in Arctic and sub-Arctic tundra of northern Siberia, from the Taimyr Peninsula eastwards to Chukotka. Occasionally, a few pairs breed in western Alaska.

It spends the winter in a vast area, from north-eastern India and Bangladesh eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea to Australia and New Zealand.

The specific name is derived from the Latin rufus (‘reddish’) and collum (‘neck’), alluding to the breeding plumage. In winter, the underside is almost pure white.

Red-necked stint at its breeding site, Schirnaya Mountains, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Incubating red-necked stint, well hidden among withered grass, Schirnaya Mountains. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nest of red-necked stint, Schirnaya Mountains. Nesting material includes leaves of dwarf birch (Betula nana). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris temminckii Temminck’s stint

This small species is a common breeding bird in a vast area, from central and northern Scandinavia and northern Finland eastwards across Arctic and sub-Arctic tundra of Russia and Siberia to Chukotka, and also on the New Siberian Islands.

In his book Arktisk sommer, Jens Gregersen says: “When I arrived at Tobseda near the delta of the Pechora River in June 2003, I was well received by Dutch zoologist Rudolf Drent (1937-2008). “Look at the small helicopter!” he exclaimed. What he referred to was a Temminck’s stint, which stood motionless in the air, sounding like some distinct grasshopper.”

What he referred to was the remarkable courtship display of the male Temminck’s stint, in which he partly stays motionless in the air with swirling wings, partly runs after the female with lifted wings.

The specific and common names commemorate Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck (1778-1858), who was the first director of the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, from 1820 until his death. He described this stint in 1815.

Temminck’s stint, near Anadyr Airport, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nest of Temminck’s stint, Kosa Ruskaya Koshka, Chukotka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calidris tenuirostris Great knot

As its name implies, this is a large species of Calidris, only slightly smaller than the ruff (above). It breeds in mountains in Arctic and sub-Arctic tundra of north-eastern Siberia, from Yakutia eastwards to Chukotka. It is a regular visitor to western Alaska.

The population of this bird has decreased alarmingly, mainly due to destruction of many of its feeding areas in China, on which it is dependent on its way to the wintering areas in Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, New Guinea, and Australia. These feeding areas have been converted into salt pans, shrimp farms, and rice fields. Today, the bird is listed as endangered by IUCN.

The specific name is derived from the Latin tenuis (‘slender’) and rostrum (‘bill’).

The pattern on breast and back in the breeding plumage of the great knot blends remarkably well with the surroundings. This pair in their nesting territory was observed in the Zolotoi Khrebet Mountains, Chukotka, eastern Siberia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded September 2023)