Birds in the United States and Canada

A male yellow-headed blackbird (Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus) marks his territory by singing from a fence post, near Bridgeport, eastern California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American white ibises (Eudocimus albus), taking off, Wakulla Springs, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male American robin (Turdus migratorius) in morning light, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American white pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos), Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. One bird shows its enormous gular pouch, which swells tremendously, when the bird is fishing – like some kind of basket. The bird with greyish head is an immature. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

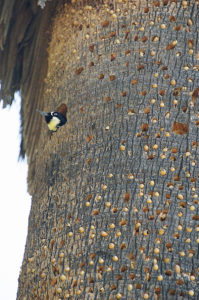

Grey jay (Perisoreus canadensis), Garibaldi Provincial Park, British Columbia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Off in the river stood a great blue heron. It was a tall bird to begin with, but something about the angle, from which they viewed it, and the cast of the low sun, made it seem even taller. It looked high as a man in the slant light with its long shadow blown out across the water. Its legs and the tips of its wings were black as the river. The beak of it was black on top and yellow underneath, and the light shone off it with muted sheen as from satin or chipped flint. The heron stared down into the water with fierce concentration. At wide intervals it took delicate slow steps, lifting a foot from out the water and pausing, as if waiting for it to quit dripping, and then placing it back on the river bottom in a new spot apparently chosen only after deep reflection.”

American author Charles Frazier (born 1950), in his excellent novel Cold Mountain, 1997.

This page shows pictures of the various bird species that I have managed to photograph in the United States and Canada.

Families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order. Nomenclature largely follows the IOC World Bird List (worldbirdnames.org). Information about etymology is often based on J.A. Jobling, 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London.

In case you encounter any errors on this page, I would be grateful to hear about it. You can use the address at the bottom of the page.

Accipitridae Hawks, eagles, and allies

A huge family, comprising about 66 genera and c. 250 species of small to large raptors, distributed worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica.

Buteo Buzzards

Members of this genus, counting about 28 species, are distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. In the Old World, these birds are known as buzzards, whereas the word hawk is often used in North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common buzzard (Buteo buteo).

Buteo lineatus Red-shouldered hawk

There are 5 subspecies of this raptor, varying in the amount of reddish-brown on the chest. It lives in open forest, breeding from south-eastern Canada southwards east of the Great Plains to Florida and Texas, and also in Oregon, California, and Baja California. The northernmost populations are migratory, wintering as far south as central Mexico. Outside the breeding season, some individuals of the resident populations stray quite far from the breeding area, and the species may be seen in almost any of the lower American states.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘lined’, alluding to the white horizontal stripes on the rufous breast.

Red-shouldered hawk of the Florida subspecies, extimus, the smallest and palest of the 5 subspecies, photographed in Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge (top), Everglades National Park (centre), and J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red-shouldered hawk of the westernmost subspecies, elegans, which is reddish-brown on the chest, but paler than the nominate subspecies. – Point Lobos State Reserve, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteo regalis Ferruginous hawk

This bird is the largest of the Buteo species in America, only slightly smaller than the upland buzzard (B. hemilasius) of Asia. It breeds in interior open grasslands and shrublands, from southern British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan southwards to Arixona, New Mexico, and extreme north-western Texas. Northern populations are migratory, wintering in southern U.S. and Mexico. Its diet includes a vast number of various mammals and birds, and also snakes and larger insects. It is often encountered in prarie dog (Cynomys) colonies.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘royal’, derived from regis, genitive of rex (‘king’). The common name means ‘rust-coloured’, borrowed from Latin ferrugineus, which is derived from ferrugo (‘rust’).

Ferruginous hawk, Badlands National Park, South Dakota. In the bottom picture, it sends out a cascade of excreta. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteo swainsoni Swainson’s hawk

This species breeds in a huge area in western United States, and also in eastern Alaska, southern Canada, and northern Mexico. Almost all birds are migratory, wintering in southern Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. A few birds may be seen in winter in Texas, Florida, and western Mexico.

The specific name honours English naturalist and artist William Swainson (1789-1855), who brought back to England a huge collection from Brazil and other places, including over 20,000 insects, 1,200 species of plants, drawings of 120 species of fish, and about 760 bird skins.

While he was generally regarded as having some expertise in zoology, his botanical career turned out to be disastrous. William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), the first director of the famous Kew Botanical Gardens, wrote about him: “In my life I think I never read such a series of trash and nonsense. There is a man who left this country with the character of a first rate naturalist (though with many eccentricities), and of a very first-rate natural history artist, and he goes to Australia and takes up the subject of botany, of which he is as ignorant as a goose.”

Swainson’s hawk, Alamogordo, New Mexico. A gust of wind ruffles its plumage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alaudidae Larks

This family contains 21 genera with about 100 species, distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species reaching the Americas, and Australia, respectively.

Eremophila Horned larks, shore larks

This genus contains only 2 species.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eremos (‘desert’) and phileo (‘to love’), alluding to the preferred habitat of Temminck’s lark (E. bilopha), which was described in 1823 by Dutch zoologist and museum director Coenraad Jacob Temminck (1778-1858). Initially, it was placed in the genus Alauda, but both horned larks were moved to Eremophila in 1828 by German zoologist and lawyer Friedrich Boie (1789-1870).

Eremophila alpestris Horned lark, shore lark

As opposed to most other larks, this species has a striking appearance, with a black stripe from the base of the bill to the eye and further down the cheek, a black breast-band, and a narrow, black, semicircular ‘crown’. In the breeding plumage, the ‘crown’ of the male is extended into two small tufts, which gave rise to the popular name.

No less than about 42 subspecies of this bird have been described, distributed across most of the Northern Hemisphere, along the Arctic coasts from Scandinavia eastwards to Alaska and north-eastern Canada, southwards to Mexico, with an isolated population in Columbia. It is also found in the major part of Central Asia, southwards to the Himalaya, westwards to Ukraine, the Middle East, and the Balkans, with an isolated population in the Atlas Mountains of north-western Africa. Arctic populations are migratory.

Horned lark, Badlands National Park, South Dakota. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horned lark, feeding on a gravel plain, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

At present, this large worldwide family contains 43 genera with about 146 species.

Anas

Many former members of this genus have been moved to other genera, and today Anas contains about 31 species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for duck.

Anas acuta Northern pintail

Avoiding the harshest areas of the Arctic, this duck, which was named due to its long, pointed tail, breeds across the Northern Hemisphere, from Iceland, Norway, and Denmark eastwards to the Pacific, and also from Alaska and Canada southwards to central United States. It is a scarce breeding bird in central and eastern Europe, and in Turkey.

The winter months are spent in the southern half of North America, in Central America and the Caribbean, in the major part of Europe and the Middle East, in northern and eastern Africa, and in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, southern China, Taiwan, and the northern Philippines.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sharp-pointed’, alluding to the pointed tail.

Pair of northern pintail, and a preening American coot (Fulica americana), Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas rubripes American black duck

This species is found in eastern North America, from eastern Manitoba eastwards to Newfoundland, southwards to the Great Lakes and New Jersey, and thence along the coast to North Carolina. Northern populations are migratory, wintering from the Great Lakes and south-eastern Canada southwards to Mississippi and northern Florida.

It is a close relative of the widespread mallard (A. platyrhynchos), and the two species often interbreed, which can make identification of pure black ducks difficult.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ruber (‘ruddy’) and pes (‘foot’).

American black ducks, Mill Neck Creek, Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anser Geese

This genus contains about 11 species, restricted to the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for geese.

Anser albifrons White-fronted goose

This bird is divided into 5 subspecies, breeding along the entire northern Siberian coastal areas, in Alaska and northern Canada, and western Greenland. The wintering areas include northern Ireland, northern Scotland, Holland, northern Germany, Hungary, the northern Black Sea coast, Iraq, the southern coast of the Caspian Sea, Japan, Korea, south-eastern China, southern United States, and northern Mexico.

The specific name is derived from the Latin albus (‘white’) and frons (‘forehead’), like the common name referring to the white feathers at the base of its bill. The salt-and-pepper markings on the breast of adult birds are distinctive of this species as well. These markings have given rise to a popular American name, specklebelly.

White-fronted geese, Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, California. The black birds in the lower picture are American coot (Fulica americana). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anser caerulescens Snow goose

This species comes in two colour morphs, a snow-white phase, which has given the bird its common name, and a bluish-grey phase, referred to as ‘blue goose’, which has given it the specific name, which means ‘bluish’.

The snow goose is mainly a bird of the New World, breeding in northern Canada and Alaska, with small populations in Greenland and north-eastern Siberia. It spends the winter along the Pacific coast, from southern British Columbia southwards, and also in southern United States and Mexico.

Snow goose, white phase, Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snow goose, blue phase, Funk National Wildlife Refuge, Nebraska. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anser rossii Ross’s goose

This species looks like a miniature snow goose, with a small bill and a relatively short neck. It breeds in the Canadian High Arctic, wintering in California, south-central United States, and northern Mexico. Previously, this goose was quite rare due to hunting, but numbers have increased dramatically as a result of conservation measures.

It was named in honour of Bernard R. Ross (1827-1874), who worked for the Hudson Bay Company in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

Ross’s goose, Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aythya

This genus, comprising 12 species, is chiefly distributed in the Northern Hemisphere, with one species occurring in New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, and on some Pacific islands, another one in New Zealand, and one in Madagascar. Two species are critically endangered, the East Asian Baer’s pochard (A. baeri) and Madagascar pochard (A. innotata).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aithyia, an unidentified seabird, mentioned by Greek grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th Century A.D.), and also by Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle (384-322 B.C.).

Aythya collaris Ring-necked duck

This common duck lives in freshwater ponds and lakes. As a breeding bird, it is distributed from eastern Alaska and north-central Canada southwards to north-western and north-eastern United States. Most populations are migratory, spending the winter in western and southern United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘necked’, derived from collum (‘neck’), in this case referring to a narrow cinnamon-coloured ring around the neck of the male, although this is often very hard to see.

Gathering of mixed waterfowl: Ring-necked duck (one beating its wings), Canada goose (Branta canadensis), American wigeon (Mareca americana), canvasback (Aythya valisineria), and ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis), Stump Pond, Blydenburgh County Park, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Branta Brent geese, brant geese

A small genus with 6 species, which breed in arctic, subarctic, and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with the exception of the Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis), which was originally restricted to Hawaii, but has been introduced elsewhere.

The generic name is a Latinized form of brandgás (‘burnt goose’), the Old Norse name of the brent goose (Branta bernicla), referring to the mainly black plumage of this species. In English, ‘burnt’ became ‘brent’.

Branta canadensis Canada goose

Seven subspecies of this very common bird breed in North America, from Alaska and northern Canada southwards to the northern third of the United States. It has also been introduced to Britain, Sweden, New Zealand, Argentina, and other places. It is very bold and has been able to establish populations in urban areas, where it has no natural predators. In many areas, it has been declared a pest because of its noise, droppings, and aggressive behaviour.

A large congregation of Canada goose, American wigeon (Mareca americana), ring-necked duck (Aythya collaris), and surf scoter (Melanitta perspicillata), Coos Bay, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canada geese with goslings, Buttle Lake, Vancouver Island. Tree trunks are reflected in the lake. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canada geese with goslings, Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing Canada geese are often a nuisance on golf courses, in this case at Glen Cove, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bucephala

This genus contains only 3 species, the bufflehead (below), Barrow’s goldeneye (B. islandica), which lives in North America and Iceland, and common goldeneye (B. clangula), which is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘bull’) and kephale (‘head’), alluding to the odd head shape of these birds.

Bucephala albeola Bufflehead

The small bufflehead breeds in taiga forests of Alaska and Canada, eastwards to western Quebec, southwards almost to the border with the United States. There are disjunct resident populations in Oregon, northern California, Montana, and Wyoming. The entire northern population migrates south, spending the winter along the Alaskan and Canadian Pacific coast, in the entire United States, and in northern Mexico.

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin albus (‘white’), thus ‘small white’ (duck). The common name refers to the head shape, a combination of ‘buffalo’ and ‘head’.

Male bufflehead, stretching its wings, Mill Neck Creek, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cygnus Swans

A genus of 6 long-necked birds, distributed on all continents except Antarctica. Genetic research indicates that the coscoroba swan (Coscoroba coscoroba) of South America is not a true swan, but more closely related to geese or shelducks.

The generic name is a Latinized form of the classical Greek term for swans, kyknos.

Cygnus columbianus Tundra swan

This smallish swan reaches a length of about 1.2 m, having a wingspan up to 2.1 m, and weighing up to 6.5 kg. Most authorities recognize two subspecies, the whistling swan (ssp. columbianus), which lives in North America, and Bewick’s swan (ssp. bewickii), which is found in Eurasia. Some authorities regard the two subspecies as separate species. They differ in bill colour, Bewick’s swan having a fairly large patch of yellow skin at the base of the bill, wheareas the whistling swan has dark skin with only a small yellow spot at the base.

If you regard these birds as a single species, it breeds in Arctic areas of Alaska and Canada, and in the northernmost parts of Siberia. The wintering areas of the whistling swan include several separate areas in western Canada, United States, and Mexico, and the central part of the Atlantic coast. Eastern populations of Bewick’s swan spend the winter in eastern China, Korea, and Japan, whereas western populations migrate to western Europe.

The total population of the whistling swan is around 200,000, and is slightly increasing. The population of Bewick’s swan is much smaller, less than 50,000, but is probably stable.

In 1803, American President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) ordered two army captains, Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838), to undertake an expedition across the western part of the North American continent, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. During their 3-year long expedition, Lewis described countless plants and animals, many of which were new to science, including the tundra swan. The whistle-like call of the bird prompted Lewis to name it whistling swan.

The specific name refers to the Columbia River, the type locality of the whistling swan.

Bewick’s swan was named in 1830 by English naturalist William Yarrell (1784-1856) in honour of English engraver Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), who specialized in illustrations of birds and other animals. He is best known for the work A History of British Birds, which contains many fine wood engravings. He also illustrated several editions of Aesop’s Fables.

Tundra swan, Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mareca Wigeons and allies

A small genus with 5 species, comprising 3 species of wigeon, the gadwall (see below), and the falcated teal (M. falcata). Previously, they were all included in the genus Anas.

The generic name is derived from Brazilian-Portuguese marréco, meaning ‘small duck’.

Mareca americana American wigeon

This common and widespread duck breeds in forest wetlands of Alaska, the major part of Canada, and in the north-western United States, from eastern Washington and Oregon through Idaho, Colorado, and the Dakotas to Minnesota. The winter is spent in south-western Canada, most of the U.S., Mexico, Central America, north-western South America, and the Caribbean.

Male and female American wigeon, Wakulla Springs, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mareca strepera Gadwall

This duck is very widely distributed, breeding in southern Canada and northern and western United States, and from England and Spain eastwards across the taiga belt to the Pacific Ocean, and the Japanese island Hokkaido. It winters in most of the United States and Mexico, in western and southern Europe, northern and north-eastern Africa, the Middle East, the northern part of the Indian Subcontinent, and in southern China.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘noisy’ – a strange name for this bird, which is not very noisy.

Male gadwall, Cathlamet, near Columbia River, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gadwall, male and female, Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mergus Mergansers

Mergansers are 4 species of fish-eating ducks, of which two, the common merganser (below) and the red-breasted merganser (M. serrator), are widely distributed across the Northern Hemisphere, whereas the Brazilian merganser (M. octosetaceus) and the scaly-sided merganser (M. squamatus) of China are highly endangered.

The generic name is a Latin word, used by Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 A.D.) as the name of an unspecified waterbird.

Previously, two other ducks were included in the genus, the hooded merganser, now called Lophodytes cucullatus, and the smew, today named Mergellus albellus. Research has shown that they are not closely related to mergansers.

Mergus merganser Common merganser, goosander

The common merganser, in Europe called goosander, nests in holes in trees. It is found in rivers and lakes in forested areas of Europe, northern and central Asia, and North America, as far south as the central Rocky Mountains, Pennsylvania, the Alps, the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, and north-eastern China. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as northern Mexico, Turkey, the Himalaya, and southern China.

The specific name is a concoction of the generic name and the Latin anser (‘goose’).

Male common merganser, Montezuma Well, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oxyura Stiff-tailed ducks

These ducks, comprising 6 species, are very distinctive, often raising their tail upwards. They are found across large parts of the globe, with 3 species in the Americas, one in Africa, one in southern Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia, and one in Australia.

Breeding males are a rich chestnut brown, females and non-breeding males brownish.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oxys (‘sharp’) and oura (‘tail’).

Oxyura jamaicensis Ruddy duck

A common species, breeding in western Canada, United States, and Mexico, around the Great Lakes, on the central part of the Atlantic coast, and in the Caribbean. Outside the breeding season, it is found in the western and southern United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean.

It has been introduced to several places in Europe, where it is regarded as an invasive species that competes with local ducks. In southern Europe, it interbreeds with the rare white-headed duck (O. leucocephala), polluting the gene pool. Efforts have been made to eradicate the ruddy duck from Europe.

Pair of ruddy duck, Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spatula Shovelers and allies

The ducks of this genus, comprising 10 species of shovelers and teals, were formerly placed in the genus Anas. The genus Spatula had originally been proposed in 1822 by German zoologist and lawyer Friedrich Boie (1789-1870), who described many new species and several new genera of birds. He and his brother Heinrich also described about 50 new species of reptiles.

The generic name is the Latin word for ‘spoon’ or ‘spatula’, alluding to the spatulate bill of shovelers.

Spatula clypeata Northern shoveler

As a breeding bird, this species is widely distributed across the northern hemisphere, avoiding the harshest areas of the Arctic. It is found from Iceland, the British Isles, Spain, and Morocco eastwards across the taiga belt to the Pacific, and also in Alaska and western North America, southwards almost to the Mexican border.

The winter months are spent in the southern half of North America, in Central America and the Caribbean, in the major part of Europe and the Middle East, in northern and eastern Africa, and in the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, southern China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the northern Philippines.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shield-bearing’, alluding to the broad and flat bill.

Feeding pair of northern shoveler, Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anhingidae Darters

Darters, also called snakebirds due to their long, thin, flexible neck, are large water birds, comprising two or four species in the genus Anhinga, the sole genus of the family. The American darter (below), often called anhinga, lives in the New World.

One or three species are found in the Old World. If only one species is acknowledged, it is called A. melanogaster. Most authorities, however, recognize three full species: Oriental (A. melanogaster), African (A. rufa), and Australasian (A. novaehollandiae).

The generic name means ‘little head’ in the Tupi language of Brazil, referring to an evil spirit of the forests, the devil bird. (Source: G. Marcgrave 1648. Historiae rerum naturalium Brasiliae. Liber V)

Anhinga anhinga American darter

This bird lives in swamps in warmer areas, found in a coastal belt from southern South Carolina southwards to Texas, on Cuba and surrounding islands, along both coasts of Mexico and Central America, and in South America east of the Andes, southwards to northern Argentina and Uruguay. Some birds stray far from the breeding area. In the U.S., the species has been observed as far north as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

American darter, drying its wings, sitting in a bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American darter, Everglades National Park, Florida. The white flowers in the background are swamp lilies (Crinum americanum). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American darter, resting in a bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), Big Cypress National Preserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Seen against the light, this American darter is drying its wings, Big Cypress National Preserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aramidae

Aramus guarauna Limpkin

This large bird, the only member of the family, is related to rails and cranes. It lives in wetlands in warmer regions, in the United States in the Okefenokee Swamp in southern Georgia and in Florida, in the Caribbean, in southern Mexico and Central America, and in South America east of the Andes, southwards to northern Argentina and Uruguay.

Its diet consists of molluscs, mainly apple snails (Pomacea).

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek aramos, a type of heron mentioned by Greek grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th Century A.D.). The specific name is the name of some marshbird in the exrinct Tupi language of Brazil. The common name stems from the gait of the bird, looking as if it limps.

Preening limpkin, standing in a large growth of water cabbage (Pistia stratiotes), Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, Florida. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This limpkin has caught a Florida apple snail (Pomacea paludosa), Lake Woodruff, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeidae Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Herons, comprising 18 genera with about 64 species, are long-legged and long-beaked, fish-eating water birds, distributed worldwide with the exception of the polar regions. Some species are called egrets, mainly birds with ornate plumes during the breeding season, whereas birds of the genera Botaurus, Ixobrychus, and Zebrilus are called bitterns.

Many members of the family are presented on the pages Fishing, and Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Ardea

A genus with about 13 species of mainly large herons, distributed almost worldwide.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons.

Ardea alba Great white egret

A large heron with an almost global distribution, found in Europe, Africa, most of Asia, Australia, and the Americas. Traditionally, it was placed in the genus Egretta (below), mainly due to its white plumage. Some authorities have also placed it in a separate genus, Casmerodius. However, it shows many affinities to large herons in the genus Ardea.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’.

Breeding colony of great white egret, Avery Island, Louisiana. In the breeding season, large plumes grow out from its back. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding great white egret, Avery Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Great white egrets, Mill Neck Creek, Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea herodias Great blue heron

This is the largest heron in America – in fact the world’s third-largest heron, only surpassed by goliath heron (A. goliath) and white-bellied heron (A. insignis). It is a common bird, breeding from central Canada southwards to Central America and the Caribbean, with a separate population in the Galápagos Islands. The northernmost populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as northern South America. Some birds in southern Florida and the Caribbean are pure white, and it is still discussed whether they form a separate species.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek erodios, the classical name of herons.

Great blue heron, feeding on a grassy plain in Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Great blue heron, taking off, Roosevelt Lake, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding great blue heron, Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Great blue heron, depicted on pavement tiles in Taiwan, with a Chinese text. They must have been delivered by an American company, as the species has never been observed in Asia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Butorides

Most authorities recognize 3 small herons of this genus as separate species, the green heron (below), the widespread striated heron (B. striata), and the lava heron (B. sundevalli), which is endemic to the Galapagos Islands. Others regard them as being conspecific.

The generic name is derived from Middle English botor (‘bittern’), and Ancient Greek oides (‘resembling’).

Butorides virescens Green heron

This small heron is breeding in the eastern half of the United States and extreme southern Canada, and also along the Pacific coast, from British Columbia southwards. In Mexico and Central America, it is found along both coasts, eastwards to Panama. It is also a resident in the entire Caribbean. Northern populations are migratory, wintering in southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘greenish’.

Green herons, Everglades National Park, Florida. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A patch of sunshine illuminates this green heron, sitting on a mangrove aerial root, J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta Egrets

The major part of the 12 small to medium-sized herons in this genus breed in warmer areas around the globe. Most members have black legs with bright yellow toes, and many develop ornate plumes during the breeding season.

The generic name is derived from Provençal French aigrette, a diminutive of aigron (‘heron’).

Egretta caerulea Little blue heron

This small heron is widely distributed in coastal areas in the southern part of North America and along the east coast to Maine, in Central America, and in South America southwards to Peru and southern Brazil. It lives in freshwater as well as brackish water. Northern populations are migratory, wintering in the Caribbean and Central America. After the breeding season, birds may stray northwards to southern Canada, southwards to Uruguay.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘blue’.

Little blue heron, feeding among aerial roots of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Little blue heron, resting on aerial roots of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Little blue heron, Everglades National Park, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta rufescens Reddish egret

This smallish heron breeds in coastal marshes, distributed in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and the Gulf States of the United States.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘reddish’, derived from rufus (‘red’).

In these pictures from J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida, a reddish egret is squabbling with a young double-crested cormorant (Nannopterum auritum). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta thula Snowy egret

This small heron, which was named after its snow-white plumage, breeds along both coasts, from Oregon and Massachusetts southwards to Central America, in the Caribbean, and in South America, southwards to central Chile and Argentina. It is also found in many scattered locations in the interior United States, where populations are migratory, wintering mainly in Mexico and Central America.

It is very similar to the Old World little egret (E. garzetta), which is described on several pages on this website, including Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

In 1782, the specific name was mistakenly applied to this bird by Chilean Jesuit priest and naturalist Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829), who didn’t realize that in fact thula was the local Mapuduncun name for the black-necked swan (Cygnus melancoryphus).

Snowy egret, walking on a floating carpet of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana), Point Lobos State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Snowy egret, J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta tricolor Tricolored heron

Also known as Louisiana heron, this species breeds in coastal marshes around the Gulf of Mexico, in Central America and the Caribbean, southwards to Peru and central Brazil.

A bird, which was banded in Virginia in 1958, was shot in the Bahamas in 1976, thus reaching the ripe age of almost 18 years.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘having three colours’.

Tricolored heron, perched on a dead tree, Everglades National Park, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tricoloured heron, J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding tricolored heron, Everglades National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bombycillidae

Previously, this family contained a number of genera, but following genetic research, all but Bombycilla have been transferred to other families, including the silky-flycatchers, which are now placed in the family Ptilogonatidae (below).

Bombycilla Waxwings

This small genus contains only 3 species: cedar waxwing (below), Bohemian waxwing (B. garrulus), and Japanese waxwing (B. japonica). These birds move nomadically outside the breeding season, the distance depending on available fruit, which is their main diet. They only migrate far distances in severe winter weather, or when fruits are scarce in their normal wintering areas.

The generic name is in fact a misnomer. French ornithologist Louis Pierre Vieillot (1748-1830) attempted to name the bird ‘silktail’ in Latin, translating the German name Seidenschwanz. He analyzed motacilla, the Latin name of the white wagtail (M. alba), as mota (‘move’) and cilla, which he thought meant ‘tail’. The word is actually derived from motare (‘to move’ or ‘to shake’), and the diminutive suffix illa, thus ‘the little shaker’, alluding to the tail of the white wagtail always bobbing up and down. However, some time during the Middle Ages the belief arose that cilla meant ‘tail’. Vieillot then combined cilla with Ancient Greek bombyx (‘silk’).

The common name alludes to the bright red tips of the secondary feathers on the wings of the Bohemian waxwing, which look like drops of sealing wax.

Bombycilla cedrorum Cedar waxwing

This bird breeds in a very large area, across southern Canada, and thence southwards to northern California, western Nevada, and northern Utah in the west, and to northern Georgia and South Carolina in the east. In winter, it spreads over a huge area, from extreme southern Canada southwards through the entire United States, the western Caribbean, and Mexico, sometimes as far south as Central America and extreme north-western South America.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of cedars’.

Cedar waxwing, eating rose hips, Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge, Georgia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cardinalidae

Members of this family, comprising 14 genera, were previously placed in the family Fringillidae (finches).

Cardinalis Cardinals

These colourful birds, comprising 3 species, are distributed from the extreme south-eastern Canada southwards to north-western South America.

The generic and common names allude to the brilliant red plumage of the northern cardinal (below), which resembles the red robes of cardinals. Originally, cardinalis is Latin, meaning ‘principal’ or ‘chief’, short for cardinalis ecclesiae Romanae, that is ‘presbyters of the cardinal (chief) churches of Rome’.

Cardinalis cardinalis Northern cardinal

This familiar bird, divided into 19 subspecies, is resident in a vast area, from extreme south-eastern Canada southwards to Florida, and thence westwards to the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Arizona, southwards through most of Mexico to northern Guatemala and Belize. It has also been introduced to southern California and Hawaii.

Male northern cardinal, Colossal Cave, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male and female northern cardinal on a bird feeder, Mount Sinai, Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young males of northern cardinal are orange-red. – Maudslay State Park, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cathartidae New World vultures

This family contains 5 genera with 5 species of vultures and 2 species of condors, distributed from southern Canada southwards to southern South America.

Cathartes

A genus with 3 species.

The generic name is a Latinized form of Ancient Greek kathartes (‘purifier’), referring to these birds getting rid of decomposing carcasses in nature.

Cathartes aura Turkey vulture

This bird is widespread and common, found from southern Canada southwards to the southernmost tip of South America. It lives in a variety of habitats, including forests, shrublands, agricultural areas, and deserts. The northernmost populations migrate south in the winter.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden’, presumably alluding to the sometimes yellowish head of the two other members of the genus. Once upon a time, they were probably all regarded as a single species. The head of the turkey vulture is always red, similar to the colour of the head of the male turkey.

Soaring turkey vultures, Big Pine Key, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turkey vulture, Salt Point State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Turkey vulture, Fakahatchee Strand State Park, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Coragyps atratus Black vulture

This species, the only member of the genus, is widely distributed in America, from southern United States southwards to central Chile and Uruguay. In eastern U.S., it may be observed as far north as New Jersey and Indiana.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek korax (‘raven’) and gyps (‘vulture’), the former alluding to the raven-black plumage of this bird. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘clothed in mourning’, derived from ater (‘black’). Very black indeed!

Black vultures, Avery Island, Louisiana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large congregation of black vultures, Lake Woodruff, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black vultures are not exactly beauties! – Lake Woodruff. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gymnogyps californianus Californian condor

In 1982, only 22 Californian condors remained in the world, a mere six in the wild. These six wild ones were captured, and a breeding program was initiated, where the eggs of the females were removed and incubated artificially. The females soon laid new eggs, and in this way a large captive population was created.

Since 1992, immature birds have been released at various places in south-western United States, and it has also been re-introduced to Baja California in north-western Mexico. In the beginning, the re-introduction faced many problems. The birds were too accustomed to being near people, some even flying inside houses, and also inside the visitors’ centre at Grand Canyon. The largest problem, however, was lead poisoning. The carcasses that the condors were eating were often shot using lead pellets, and if the birds swallowed too many of these pellets they died from lead poisoning. Some birds also died due to collision with electric wires.

Therefore, the condors were being fed with carcasses without pellets, and the population slowly began to increase. Today, the species is thriving at several locations in California, Arizona, and Utah, and also in Baja California, where a small populations is found. In 2020, the total number of birds living in the wild was around 335, and about 200 lived in captivity.

The Californian condor is the only member of the genus. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek gymnos (‘naked’) and gyps (‘vulture’), the first part alluding to its naked head. The common name is derived from kundur, the Quechua name of the Andes condor (Vultur gryphus).

Californian condors, Grand Canyon. Numbered signs have been attached to the upperside of the wings. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Charadriidae Plovers and lapwings

This family of small to medium-sized waders comprise about 10 genera with about 65 species. They are distributed almost worldwide, the vast majority near wetlands.

Charadrius Ringed plovers, dotterels

These birds, comprising about 32 species of mainly small waders, are found throughout the world, usually in wetlands.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for a yellowish bird, mentioned in Biblia Vulgata, a Latin translation of the Bible from the late 4th Century. The name was derived from the classical Greek term for a bird living in river valleys, kharadrios, derived from kharadra (‘ravine’).

Charadrius melodus Piping plover

This small plover was named for its piping call. It breeds on sandy beaches and sand flats in two separate populations, one along the Atlantic coast, from Newfoundland southwards to North Carolina, along shores of the Great Lakes, and in wetlands in the mid-west of Canada and the United States. It winters along shores in the south-eastern United States, around the Gulf of Mecico, on the Bahamas and Cuba, and also on shores of the Gulf of California.

It is threatened by development and increased traffic on the shores, and there are probably less than 10,000 individuals altogether.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘melodious’, alluding to its call.

Piping plovers, Long Island, New York State. The bird in the bottom picture was observed at its breeding place at Breezy Point. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Charadrius vociferus Killdeer

This bird, one of the largest members of the genus, breeds in most of North America, from subarctic areas of Alaska and Canada southwards to central Mexico and the Caribbean. It also breeds in a coastal belt from Ecuador southwards to southern Peru. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter in southern United States, Central America, and northernmost South America.

The common name is an imitation of its call. The specific name also refers to the call, derived from the Latin vox (‘cry’) and ferre (‘to bear’).

Killdeer, Salt Creek, Death Valley National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Killdeer, Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This killdeer plays sick to lure me away from its nest, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ciconiidae Storks

These large birds, comprising 6 genera with 19 species, are found in most parts of the world, being absent from the polar regions and the major parts of North America and Australia.

The word stork originates in Ancient Germanic sturkoz.

Mycteria Wood storks

A small genus with 4 species, distributed in most tropical areas of the world.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek mykterizo (‘to turn up the nose’), from mykter (‘snout’). Presumably, it refers to the large bill of these birds, causing them to raise their ‘nose’.

Mycteria americana Wood stork

This species is not very attractive, having a naked and wrinkled black head and upper neck, reflected in some of its local names, including ‘flinthead’, ‘stonehead’, and ‘ironhead’.

It is widely distributed in the Caribbean, and Central and South America, southwards to northern Argentina. There are also small populations in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. These northern populations are partly migratory, and in winter it may be encountered around the Gulf of Mexico, and also along the Mexican Pacific coasts.

This wood stork has caught a fish, J. N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wood storks, Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young wood stork, shaking its feathers, Everglades National Park, Florida. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Columbidae Pigeons and doves

A large family with about 50 genera and c. 345 species. The word pigeon generally denotes larger species, dove smaller species. These birds are found on all continents except Antarctica.

Columbina

This genus of small doves, comprising 9 species, ranges from southern United States southwards to the major part of South America.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘dove-like’, derived from columba (‘dove’).

Columbina inca Inca dove

A small, greyish bird, easily identified by its scaly pattern, rust-coloured primaries, and white outer tail feathers, often displayed in flight. It is widespread, found from southern California eastwards to south-western Louisiana, and thence southwards to Costa Rica.

The specific name is a misnomer, as this species does not occur in lands of the former Inca Empire. Presumably, French naturalist René Primevère Lesson (1794-1849), who named the bird in 1847, thought that the specimen originated in South America.

Inca dove, Granite Reef, Salt River, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patagioenas

This is a group of 17 pigeons, which were formerly placed in the genus Columba. They are distributed in the major part of the New World.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek patageo (‘to clatter’) and oinas (‘pigeon’). Presumably, the name alludes to the wing-clapping of several pigeons when taking off.

Patagioenas fasciata Band-tailed pigeon

A fairly large pigeon, to 40 cm long, breeding from southern British Columbia southwards through Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Mexico, and Central America to northern South America, and thence along the Andes to northern Argentina. The northernmost populations are migratory.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘banded’, like the common name alluding to a dark band across the centre of the tail, dividing it into a dark grey base and a pale grey outher half.

Band-tailed pigeon, Yosemite National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zenaida

There are seven species of smallish doves in this genus, distributed from southern Canada southwards to southern South America.

The generic name was introduced in 1838 by French ornithologist Charles Bonaparte (1803-1857), 2nd Prince of Canino and Musignano, in honour of his wife Zénaïde (1801-1854).

Zenaida asiatica White-winged dove

In flight, this striking bird displays crescent-shaped white wing-patches and black flight-feathers, and it also has a bright blue patch of naked skin around the eye.

Despite its specific name asiatica, meaning ‘from Asia’, this dove is a New World bird, distributed in south-western United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Presumably, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who named this bird Columba asiatica in 1758, was told that the type specimen originated in Asia.

White-winged dove, photographed near Tucson, Arizona. The bird in the upper picture is cooing from atop a saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zenaida macroura Mourning dove

This species is abundant in North America, breeding from southern Canada southwards to southern Mexico and the Caribbean. It may rear up to six clutches a year. The northernmost populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as Panama.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek makros (‘long’) and oura (‘tail’), referring to the long tail of this bird. The common name refers to its call, which sounds rather mournful.

Mourning dove, Oasis of Mara, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mourning dove, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corvidae Crows and allies

This almost cosmopolitan family contains 24 genera with more than 120 species of ravens, crows, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs, nutcrackers, and others.

A large number of species are described on the page Animals – Birds: Corvids.

Aphelocoma Scrub jays

Previously, this genus contained only 3 species, but a number of splits have increased the number to 7. They are medium-sized birds with a mainly blue and grey plumage, living in western United States, Mexico, and western Central America, eastwards to western Nicaragua, with an isolated species in Florida.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek apheles (‘naïve’, but in this connection translated as ‘simple’) and kome (‘well-tended hair’), given in allusion to the lack of stripes or bands on these birds, compared to other jays.

Aphelocoma californica California scrub jay

This species is native to a broad coastal belt in western North America, from extreme southern British Columbia southwards through Washington, Oregon, California, and extreme western Nevada, to the southern tip of Baja California. It lives in low scrub, piñon-juniper forests, oak woods, and also in suburban gardens, where it often becomes confiding, feeding at bird feeders.

This bird was once lumped with 3 other species, collectively simply called the scrub jay. Then two populations were split to form separate species, the Florida scrub jay (A. coerulescens), which lives in Florida, and the island scrub jay (A. insularis), which is confined to Santa Cruz island off the Californian coast. The remaining populations were now called western scrub jay. Later, the inland populations were split to form a new species, Woodhouse’s scrub jay (A. woodhouseii), whereas the coastal populations were named California scrub jay.

California scrub jay, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aphelocoma wollweberi Mexican jay

This bird, with blue upperparts and grey underparts, was formerly known as grey-breasted jay (A. ultramarina), but in 2011 it was split into two species, the northern populations now called Mexican jay, with the Latin name A. wollweberi, whereas the central Mexican population, now called Transvolcanic jay, retained the name A. ultramarina.

The Mexican jay is distributed from eastern Arizona and western New Mexico southwards along the Sierra Madre Occidental, almost to Mexico City, and thence northwards along the Sierra Madre Oriental to the Chisos Mountains in southern Texas.

The specific name honours a German traveller, named Wollweber, who collected birds in Mexico in the 1840s for the Darmstadt Museum in Germany. Apart from that we know nothing about him, as the archives of the Darmstadt Museum were destroyed during World War II.

Mexican jay, Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corvus Ravens, crows, rooks

This genus with about 45 members occurs in virtually all temperate areas of the globe, with the exception of South America. The name raven applies to the largest species, crow and rook to slightly smaller species. Members of this genus are among the most intelligent birds.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common raven (C. corax).

Corvus brachyrhynchos American crow

This bird is distributed in the major part of North America, from southern Canada southwards to Florida and northern Mexico. It is quite similar to the common raven (below), but is smaller, with a slender and short bill, reflected in the specific name, from Ancient Greek brachys (‘short’) and rhynchos (‘bill’).

American crows, Mill Neck Creek, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American crow, perched in a dead Torrey pine (Pinus torreyana), Torrey Pines State Beach, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This American crow is sitting on an old-fashioned windmill, which was once used to pump up drinking water for cattle, Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American crow, Sunset Point State Park, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

American crow, feeding on a dead crab, Sunset Point State Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corvus corax Common raven

Divided into at least 8 subspecies, the common raven is the most widespread member of the family, occurring in almost all arctic and temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere. With a length of up to 63 cm, and weighing up to 1.2 kg, it is the second-largest of passerines, only slightly smaller than the thick-billed raven (C. crassirostris) of Ethiopia. Ravens have been known to live more than 23 years in the wild.

The specific name is a Latinized form of the classical Greek word korax, meaning ‘raven’ or ‘crow’. The English name derives from Old Norse hrafn, ultimately from Proto-Germanic khrabanas.

Due to its intelligent behaviour, the raven appears in numerous mythologies. In Norse mythology, the ravens Hugin (‘thought’) and Munin (‘memory’) were the servants of the supreme god Odin, bringing news to him from all over the world. The raven figured on banners of Norse kings like Cnut the Great and Harald Hardrada.

The raven was also an important bird to the Celts. According to Irish mythology, the goddess Morrígan alighted on the hero Cú Chulainn’s shoulder in the form of a raven after his death. In Welsh mythology, the name of the god Bran Fendigaid (in English called ‘Bran the Blessed’) means ‘raven’, and the bird was his symbol.

Among a number of peoples in Siberia, north-eastern Asia, and North America, the raven was regarded as a creator god. To the Tlingit and Haida peoples of Pacific North America, it was also a trickster.

Genesis 8: 6-7 says, “So it came to pass, at the end of forty days, that Noah opened the window of the ark, which he had made. Then he sent out a raven, which kept going to and fro, until the waters had dried up from the earth.”

Calling raven, Laguna Point, Mackerricher State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Presumably, this raven, perched atop an eroded bluff in Red Rock Canyon State Park, Mohave Desert, California, has found something interesting. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This raven is sitting on a sign in Death Valley National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Raven, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Raven, Salt Point State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cyanocitta

A small genus with only 2 species, the blue jay (Cyanocitta cristata), which lives in southern Canada and the eastern and central United States, and Steller’s jay (below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyanos (‘dark blue’) and kitta (‘jay’), alluding to their predominant colour.

Cyanocitta stelleri Steller’s jay

This striking bird is found along the Pacific coast, from southern Alaska southwards to California, and also inland along the Rocky Mountains, the Mexican Sierra Madre Occidental, and various montane areas southeast to Nicaragua.

The specific and common names commemorate German naturalist and explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709-1746), born Stöhler, who participated in the Russian Great Northern Expedition (1733-1743), also known as the Second Kamchatka Expedition, led by Danish explorer Vitus Jonassen Bering (1681-1741). Steller is considered a pioneer of Alaskan natural history.

Steller’s jay, Bridgeport, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Steller’s jay is investigating my car in search of food, Redwood National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nucifraga Nutcrackers

Formerly, it was believed that this genus contained only 2 species, Clark’s nutcracker (below), found in western North America, and the Eurasian spotted nutcracker (N. caryocatactes). Following genetic and other research, the spotted nutcracker has been divided into 3 species, the northern nutcracker (N. caryocatactes), found in Europe and northern Asia, the southern nutcracker (N. hemispila), which lives in the Himalaya, western and northern China, and Taiwan, and the Kashmir nutcracker (N. multipunctata), which is restricted to Kashmir.

The most important food item for these birds are seeds of various pines (Pinus), which they break open with their powerful bill. This fact is reflected by the generic name, which is derived from the Latin nuci (‘nut’) and frango (‘to break’).

When pine nuts are abundant, they make caches of surplus seeds, storing as many as 30,000 in a single season. They are able to remember the location of as many as about 70% of their stash, even when buried in snow. They often store the nuts far away from where they were collected, and are thus important in re-establishing forests in logged or burned areas. (Source: D.F. Tomback 2016, in Why birds matter: avian ecological function and ecosystem services, edited by Sekercioglu, Wenny & Whelan, University of Chicago Press)

In regions without pine trees, seeds of spruce (Picea) and hazelnuts (Corylus) form an important part of the diet.

Nucifraga columbiana Clark’s nutcracker

A pale grey, black, and white nutcracker, native to the mountains of western North America, from British Columbia and western Alberta southwards to southern California and New Mexico, living mainly in coniferous forests at altitudes between 900 and 3,900 m. There is a small isolated population on the mountain Cerro Potosí in Nuevo León, north-eastern Mexico.

This bird was described by Captain Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) during the Lewis and Clark expedition 1803-1806. The first observation was done by Captain William Clark (1770-1838) in 1805 along the banks of the Salmon River, a tributary of the Columbia River – hence the specific name.

Clark’s nutcracker, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Clark’s nutcrackers, drinking from a meltwater puddle on the crater rim, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Perisoreus

A small genus with 3 species, distributed in coniferous forests of North America, Eurasia, and western China.

Perisoreus canadensis Canada jay, grey jay

This species is mainly white, with grey wings and tail, and a dark-brown crown. It ranges widely across northern North America, from subarctic Alaska and Canada eastwards to Newfoundland and Labrador, southwards along the Pacific Range to northern California, and along the Rocky Mountains southwards to Arizona and New Mexico. It also reaches the northern part of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and New England, and the Adirondack Mountains in New York. In winter, it may be seen even further south.

This bird is known by several popular names, including whisky jack, which is a corruption of Wisakedjak, a benevolent trickster and cultural hero in Cree, Algonquin, and Menominee mythologies. Among the Tlingit people of north-western North America it is known as kooyéix or taatl’eeshdéi, meaning ‘camp robber’, alluding to its tameness.

Grey jay, Lake Schoen, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The grey jay is very confiding. This one in Garibaldi Provincial Park, British Columbia, takes food from a hiker’s boot. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is sitting on my sandal, Redwood National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one takes bread, which has been placed on a little girl’s head, Mount Rainier, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Falconidae Falcons and caracaras

This family, counting about 60 species, is divided into 3 subfamilies, Herpetotherinae (laughing falcon and forest falcons), Polyborinae (caracaras and Spiziapteryx), and Falconinae (typical falcons and falconets).

Genetic research has shown that these birds are not closely related to raptors of the family Accipitridae. Their similar feeding habits are an example of convergent evolution.

Falco Typical falcons

The largest genus of the family, comprising about 40 species. It is widely distributed on all continents, except Antarctica.

The generic name is derived from the Latin falx, or falcis (‘sickle’), referring to the talons.

Falco sparverius American kestrel

This is the smallest falcon in America, growing to about 30 cm long. It is divided into about 17 subspecies, and is found in the entire Americas, with the exception of the Arctic, rainforest areas, and the very dry deserts in Chile. It lives in a wide variety of open habitats, including grasslands and farmland, and it has also adapted to urban areas.

The specific name is the Latin word for sparrowhawk. In 1731, the bird was named ‘little hawk’ by English naturalist Mark Catesby (1683-1749), who studied flora and fauna in the New World.

This male American kestrel, which had been damaged, was brought to a centre for damaged birds at Tucson Desert Zoo, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fringillidae Typical finches

A large family with c. 228 species, divided into about 50 genera. These birds are distributed worldwide, except for Australia and the polar regions. Most species have stout conical bills, adapted for eating seeds and nuts.

Haemorhous American red finches

Previously, the house finch (below), together with the purple finch (H. purpureus) and Cassin’s finch (H. cassinii), were lumped with the Old World rosefinches (Carpodacus). However, genetic research has shown that they are not closely related, despite their similar appearance. They have therefore been moved to a separate genus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek haima (‘blood’) and orrhos (‘rump’).

Haemorhous mexicanus House finch

This bird was originally native to western North America, but has been introduced to the eastern half of the United States. Today it is common and widespread across the continent, from southern Canada southwards to southern Mexico.

Male house finch, Oasis of Mara, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spinus Siskins and New World goldfinches

A genus with 17 species, 15 of which live in the New World, while the Eurasian siskin (S. spinus) and the Tibetan siskin (S. thibetanus) are found in Eurasia. 16 species were formerly placed in the genus Carduelis, the Tibetan siskin in Serinus.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘thorn’. Originally, the word was applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), as Carduelis spinus, to the Eurasian siskin, presumably due to its very fine and pointed bill, an adaptation to eat the small seeds of alders (Alnus).

Spinus tristis American goldfinch

This gorgeous bird is widespread across the North American continent, breeding from southern Canada southwards to central United States. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter in the southern U.S., from southern California eastwards to Florida, and also in eastern Mexico.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sad’ or ‘gloomy’. It is strange, why this name was applied to this beautiful bird, but maybe it was described from the skin of a female, which is brown in the parts, in which the male is bright yellow.

Male American goldfinch, Cathlamet, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male American goldfinch, feeding on seeds of sunflower (Helianthus annuus), Old Westbury Garden, Long Island, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gaviidae Loons, divers

This small family contains 5 species, all members of the genus Gavia, and all restricted to the Northern Hemisphere. In America they are called loons, in England divers.

The generic name is the Latin word for some unidentified seabird.

Gavia immer Common loon, great northern diver

This large bird is mainly a New World species, breeding in subarctic areas of Alaska and Canada, and also in far north-western United States and around the Great Lakes. It also breeds in southern Greenland and Iceland, and small numbers on Jan Mayen, Svalbard, and Bear Island in Norway.

In winter, American birds are found along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, ranging as far south as central Mexico on the Pacific side, and Texas on the Atlantic side. North Atlantic birds spend the winter around Iceland and along coasts of northern and western Europe, as far south as Portugal.

The specific name is the Norwegian name for the common loon. It is perhaps originally a Norse word, as the Icelandic name of the bird is himbrimi (‘surf roarer’). Icelandic names are often much closer to the original Norse words than the Scandinavian names.

Common loon, Humboldt Wildlife Refuge, California (top), and Lake Schoen, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gruidae Cranes

Cranes are medium-sized to large birds, comprising 15 species, divided into two subfamilies, Balearicinae with two species of crowned cranes in one genus, Balearica, and Gruinae with 13 species, which were once all placed in one genus, Grus, while the latest genetic studies divide them into three genera: Leucogeranus (1 species), Grus (8 species), and Antigone (4 species). The crowned cranes split out from true cranes at a very early stage, about 10 million years ago.

Antigone

Besides the sandhill crane (below), this genus contains the sarus crane (A. antigone) and the white-naped crane (A. vipio) in Asia, and the brolga crane (A. rubicunda) in Australia. They were formerly placed in the genus Grus.

In Greek mythology, Antigone was the daughter of Oedipus, who unwittingly killed his father Laius, king of Thebes, and married the widow, his mother Jocasta. When Jocasta learned the truth of their relationship, she hanged herself, and Oedipus, according to one version of the story, went into exile after blinding himself, accompanied by his daughters Antigone and Ismene.

Antigone canadensis Sandhill crane

The most numerous crane species in the world, numbering more than 1.2 million, and the population is still increasing, undoubtedly because the cranes have easy access to waste maize in the winter.

Today, five subspecies are recognized: canadensis, which breeds in eastern Siberia, Alaska, and northern Canada. It is the most abundant of the subspecies, comprising about 500,000 birds; tabida, which breeds in southern Canada, and northern and western U.S.; pratensis, which is found in Florida and the southernmost part of Georgia; pulla, which is restricted to the south-eastern corner of the state of Mississippi; and, finally, nesiotes, which is only found on Cuba. A sixth subspecies, rowani, is no longer accepted, and some authorities only acknowledge two subspecies, canadensis and tabida. The populations in Mississippi and on Cuba are very small and threatened with extinction.

Northern populations, including the Siberian breeding birds, spend the winter in south-western U.S. and Mexico, whereas the southern populations are resident.

The sandhill crane has spread considerably in Siberia in later years and is now a threat to many bird species by eating their eggs and young. This issue is described on the page Animals – Birds: Sandhill cranes – a threat to breeding birds.

Every spring, between mid-February and mid-April, up towards 1.2 million sandhill cranes visit the central part of the Platte River, Nebraska, resting and feeding in this area, before migrating to the breeding grounds further north. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sandhill cranes, feeding on waste maize from the previous year, Grand Island, Nebraska. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sandhill cranes, subspecies tabida, Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grus Typical cranes

Today, this genus contains 8 species, distributed in Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America.

Grus americana Whooping crane

Previously, the whooping crane was found in wetlands in the central parts of North America, from Alberta southwards to south of Lake Michigan. In winter, the birds migrated to the Mexican highlands, Texas, and the Atlantic coast. There was also a resident population in Louisiana and possibly elsewhere in the southern states.

It has been estimated that prior to the arrival of the Europeans, the population counted at least 10,000 individuals. It steadily declined, and in the late 1800s fewer than 1,500 remained. The species was still regarded as a pest, and the population declined drastically. By 1938, only about 20 individuals remained. After World War II, a conservation campaign was initiated to persuade hunters and farmers not to shoot the magnificent birds.

In 1954, the last remaining breeding place of the whooping crane was found in Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada, and an intensive research program began. An egg was taken from nests with two eggs. (This could be done without hesitation, as only one young survives from each nest.) The collected eggs were incubated artificially, and the young were kept for a breeding program. The only known wintering area, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas, was already protected. The population of cranes slowly increased, and in 1969 there were 68 birds.

Between 1975 and 1988, 380 whooping crane eggs were placed in nests of sandhill cranes in Idaho. But although 38 young made it to adulthood, they were behaving like sandhill cranes, and no young were produced in the flock. The experiment was stopped.

Since 1993, several hundred birds raised in captivity have been released in Florida, with the hope of creating a local population of resident birds. By 2003, 95 had survived, and since 2000 a few young have made it to adulthood. The problem is that bobcats (Lynx rufus) and other carnivores eat the young. In 2018, the wild population here was 14 individuals, while 163 were kept in captivity.

In 2001 and 2002, altogether 21 young whooping cranes, reared in Wisconsin, were trained to follow an ultralight plane, and in the autumn they followed the plane to Florida. This population, numbering 90 in 2007, now migrate on their own between Wisconsin and Florida. Since 2006, this flock has produced a few young, which migrate with the adults to Florida.

In 2011, a new population was established in south-western Louisiana from 10 young birds, reared in captivity. In 2018, this flock counted 54 birds.

Overall, the effort has been a succes. In 2008, the total population of whooping cranes was 270 birds, increasing to 849 in 2018.

This magnificent bird was saved in the nick of time, but it is still the rarest crane species in the world, threatened by inbreeding, draining programs, and collisions with high-voltage wires. In Aransas, the most important wintering area, a new road has stopped the inflow of water from the rivers. This has caused the population of the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus), which constitutes the most important food item for the cranes, to decline. Oil drilling is taking place in the vicinity, and a few times petro-chemical products from trucks have been seeping into the area, polluting it.

The most important wintering area for the whooping crane is Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas, where this picture was taken by my late friend Uffe Gjøl Sørensen. This bird has caught a blue crab (Callinectes sapidus), the most important food item of the species in this area. One crane is able to consume 80 of these crabs a day! (Photo Uffe Gjøl Sørensen, copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Whooping crane, depicted on pavement tiles in Taiwan, with a Chinese text. They must have been delivered by an American company, as the species has never been observed in Asia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hirundinidae Swallows and martins

A large family with 19 genera and about 90 species, distributed around the world on all continents, including Antarctica, where the barn swallow (below) is an occasional visitor. The greatest diversity is found in Africa.

Hirundo

This genus contains about 16 species, all except one restricted to the Old World. The barn swallow (below) also occurs in the Americas.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for swallow.

Hirundo rustica Barn swallow

Comprising 6 subspecies, this is the most widespread swallow in the world, breeding across the major part of the Northern Hemisphere, from the British Isles eastwards to Japan, and from northern Norway, central Siberia, and Kamchatka southwards to North Africa, Egypt, southern Iran, and southern China, and in most of North America, from northern Canada southwards to southern Mexico.

Four subspecies are migratory, spending the winter as far south as South Africa, northern Australia, and Argentina. The birds may be seen year-round in southern Mexico, southern Iberian Peninsula, Egypt, the Himalaya, southern China, and Taiwan.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rural’, derived from ruris (‘countryside’). In his Historiæ animalium, Liber III, published in 1555, Swiss physician and naturalist Konrad Gessner (1516-1565) calls the bird Hirundo domestica, from the Latin domus (‘house’). The barn swallow mostly builds its nest on or inside buildings, very often in stables or barns – hence its common name.

Barn swallows, resting on a piece of handicraft, depicting an Atlantic sailfish (Istiophorus albicans), Reeds Beach, Cape May, New Jersey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Barn swallows, Birch Bay, Washington State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Petrochelidon Cliff swallows

Members of this genus, comprising about 10 species, are found on all continents, except Europe and Antarctica.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek petros (‘rock’) and khelidon (‘swallow’), alluding to a type of swallow building its nest on rocks.

Petrochelidon pyrrhonota American cliff swallow

A very widespread bird, breeding from southern Alaska and western and south-eastern Canada southwards to southern Mexico, spending the winter in central South America.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek pyrrhos (‘flame-coloured’) and notos (‘-backed’), but the bird was originally described as golondrina rabadilla acanelada (‘swallow with cinnamon-coloured rump’) by Félix de Azara (1746-1821), who was a member of a delegation that was sent to the Río de la Plata region in 1777 to negotiate the border dispute between the Portuguese and Spanish colonies. de Azara ended up spending about 20 years in the area, until 1801. He drew an accurate map of the region, and also began studying birds and mammals, of which he described many new species.

American cliff swallows, collecting mud for nest building, Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, Oregon. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stelgidopteryx Rough-winged swallows

A small genus with only 2 species, widespread in the Americas.

Like the generic name, derived from Ancient Greek stelgis (‘scraper’) and pteryx (‘wing’), the common name refers to the serrated edge of the wing feathers of these birds.

Stelgidopteryx serripennis Northern rough-winged swallow

This bird breeds in a vast area, from southern Canada southwards to Costa Rica, and also in the Caribbean. In winter, northern populations migrate to the southern United States, Mexico, and Central America.

The specific name is derived from the Latin serra (‘saw’) and penna (‘feather’), thus roughly the same meaning as the generic name.

Northern rough-winged swallows, Coon Bluff, Salt River, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tachycineta Tree swallows

This genus, which contains 9 species, is found in the entire Americas, except in the Arctic.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek takhys (‘fast’) and kineto (‘movement’).

Tachycineta bicolor Tree swallow

Breeding in North America, this species ranges from central Alaska and the major part of Canada as far south as Tennessee, Kansas, New Mexico, and California, wintering from southern United States southwards through Mexico and Central America to the extreme north-western South America, and also in the Caribbean.

It nests in holes, and was formerly restricted to forested areas, but since the introduction of nest boxes it is also found in open habitats.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with two colours’.

Tree swallow on a nesting box, Sands Point Preserve, Long Island, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Icteridae