Birds in the Indian Subcontinent

Sri Lanka blue magpie (Urocissa ornata), Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spot-billed pelicans (Pelecanus philippensis) in their breeding colony in the village of Kokkare Belur, near Mysore, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On a hot spring day, a splendid peacock (Pavo cristatus) quenches his thirst at a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. The bird behind it is a red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus), reflected in the pond. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

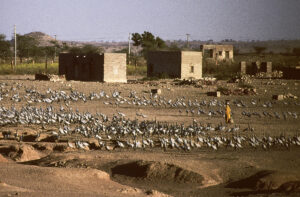

A huge flock of demoiselle cranes (Grus virgo), resting in the Thar Desert, near Kichan, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sri Lanka junglefowl (Gallus lafayetii), Sinharaja Forest Reserve, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus) in evening light, near Jodhpur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

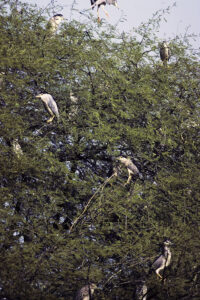

White-rumped vultures (Gyps bengalensis), basking in the morning sun, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

”Almost any small animal will be attacked, and I have seen full-grown bulbuls and palm squirrels captured by it; eggs and nestlings are, of course, its delight.”

British ornithologist and entomologist George Morrison Henry (1891-1983) about the large-billed crow (Corvus macrorhynchos), in his book A guide to the Birds of Ceylon, first published 1955, 2nd ed. 1971.

This page deals with a selection of birds, which I have encountered during numerous visits to India, Pakistan, southern Nepal, and Sri Lanka, between 1974 and 2015. Birds observed in the Himalaya are presented on a separate page, see Animals – Birds: Birds in the Himalaya.

Families, genera and species are presented in alphabetical order. Nomenclature largely follows the IOC World Bird List (worldbirdnames.org), whereas information about etymology is often based on J.A. Jobling 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London.

As is obvious from most of the pictures below, I like to show the birds in their natural surroundings, or studies of their behaviour.

In case you find any errors on this page, I would be grateful to receive an email. You may use the address at the bottom of the page.

Map, showing Indian states and union territories. (Borrowed from www.mapsofindia.com)

Accipitridae Hawks, eagles, and allies

A huge family, comprising about 66 genera and c. 250 species of small to large raptors, distributed worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica.

Accipiter Sparrowhawks, goshawks

Comprising about 50 species, this is the largest genus in the family. In Europe, these birds are known as sparrowhawks (smaller species) or goshawks (larger species), in America simply as hawks. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for hawks, derived from accipere (‘to grasp’), naturally alluding to the sharp talons.

Accipiter badius Shikra

This small raptor, divided into 6 subspecies, is distributed in open habitats in a vast area, from the Caucasus and southern Kazakhstan southwards to the Indian Peninsula, and thence eastwards to Indochina and the southernmost parts of China, and also from Senegal and Gambia eastwards across the Sahel zone to southern Sudan, Eritrea, south-western Saudi Arabia, and western Yemen, and thence southwards to central Namibia and northern South Africa, avoiding the rainforest area of the Congo Basin.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘chestnut-coloured’, alluding to the barring on the chest. The common name is Hindi, meaning ‘hunter’.

Shikra, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Evening light on a shikra, resting on a sandstone pole, Gudi, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquila True eagles

A genus with 11 species, found in most parts of the world, except the polar regions, South America, and rainforest areas.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for eagle, perhaps derived from aquilus (‘dark in colour’).

Aquila heliaca Imperial eagle

This species breeds from eastern Europe and Turkey across the Central Asian steppes to south-central Siberia, Mongolia, and northern China. It is migratory, spending the winter at scattered locations from Turkey and the Nile Delta eastwards to eastern China, Korea, and southern Japan, southwards to Kenya, northern India, and Indochina.

Previously, birds in southern Spain and Portugal were regarded as a subspecies of the imperial eagle, but are now generally considered a separate species, the Iberian imperial eagle (A. adalberti).

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek heliakos (‘of the sun’), from helios (‘sun’), or heleios, a kind of hawk mentioned by Greek grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th Century A.D.) in his work Lexicon.

Adult imperial eagle, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquila nipalensis Steppe eagle

A large eagle, breeding from eastern Ukraine eastwards across the Asian steppes to northern China. It differs from other eagles in mainly nesting on the ground, and it has specialized in feeding on ground squirrels. It is migratory, spending the winter from Arabia eastwards to southern China, and in eastern and southern Africa.

The specific name was given by British naturalist and ethnologist Brian Houghton Hodgson (1801-1894), who described the bird in 1833 after collecting a specimen in Nepal. Presumably, he thought that it was a local species.

Immature steppe eagles, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aquila rapax Tawny eagle

Divided into 3 subspecies, this eagle is breeding in the Indian Subcontinent, in the major part of sub-Saharan Africa, and in scattered locations in north-western Africa, south-western Arabia, and Iran. The plumage is highly variable, with distinct pale and dark morphs, and various intermediate forms.

In some plumages, this species is very similar to the steppe eagle (above), but the yellow gape of that species extends to the back end of the eye, whereas the gape of a tawny only extends to the middle of the eye. However, you have to be rather close to the bird to observe the difference.

The specific name is derived from the Latin rapere (‘to seize’).

Tawny eagle, taking off from a tree, Geramki Dhani, Thar Desert, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteo Buzzards

A genus of about 28 species, distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. In the Old World, these birds are known as buzzards, whereas the term hawk is often used in North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common buzzard (B. buteo). The English name is derived from Old French busard, which is a corruption of the classical Latin name.

Buteo rufinus Long-legged buzzard

This large buzzard breeds in a vast area, from eastern Europe eastwards to Xinjiang, southwards to Arabia, Iran, and Afghanistan, and also in northern Africa. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as Bangla Desh, northern India, Iran, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden-reddish’, alluding to the mainly rufous plumage of the bird.

Long-legged buzzard, taking off from a sandstone pillar, Lathi, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Circaetus Snake-eagles

As their name implies, these birds feed mainly on snakes. There are 7 species, all restricted to Africa with the exception of the short-toed eagle (below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kirkos, a type of hawk, in this connection associated with harriers (Circus); and aetos (‘eagle’).

Circaetus gallicus Short-toed eagle

A widely distributed eagle, breeding from the Baltic States eastwards to western Mongolia and northern China, southwards to the entire Indian Peninsula, and thence westwards to the Middle East, Arabia, southern Europe, and north-western Africa. With the exception of the birds in Pakistan and India, all populations are migratory, mainly spending the winter in the Sahel Zone of Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from Gaul’, a term that in the Roman Era covered the major part of western Europe.

Short-toed eagle, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Clanga Spotted eagles

A small genus with 3 species, distributed from eastern Europe across the boreal zone of Siberia to the Pacific Ocean, and one resident species in northern India. The two northern species are migratory. They were previously placed in the genus Aquila (above).

In Ancient Greek, klangos was an alternative form of plankos, the name of a kind of eagle. In classical Latin, clango had several meanings, including ‘I scream’. Thus, the generic name may be translated to ‘ the screaming eagle’.

Clanga clanga Greater spotted eagle

A uniform dark brown eagle with very broad wings and a short tail. A good field mark is a whitish ‘comma’ at the wrist of the underwing. Immatures have numerous prominent whitish spots on the back and upperwing.

It breeds from eastern Europe eastwards across the taiga belt to north-eastern China and Ussuriland (south-eastern Siberia). It is migratory, spending the winter in southern Europe, north-eastern Africa, Arabia, the Middle East, the northern part of the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, and eastern China.

Greater spotted eagle, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. Note the white ‘comma’ at the wrist of the underwing. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elanus Small kites

Members of this genus, comprising 4 quite similar species of small white, grey, and black raptors, are distributed throughout almost the entire globe, although they avoid colder areas.

The generic name is a Latinized form of elanos, the classical Greek word for kite.

Elanus caeruleus Black-winged kite

This bird has a very wide distribution, found in all of sub-Saharan Africa, in north-western Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, France, the Nile Valley of Egypt, at several locations throughout the Middle East, from the entire Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia and New Guinea.

The specific name is derived from the Latin caelum, which, strictly speaking, means ‘sky’, but is often used to indicate the colour ‘sky-blue’; and a diminutive suffix, thus loosely translated as ‘the small sky-blue one’, referring to the bluish sheen in the plumage.

Black-winged kite, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-winged kite, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gyps Griffon vultures

This genus contains 8 species of carrion-eating raptors, distributed in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The generic name is the classical Greek term for vultures.

Since the 1980s, most populations of vultures in the Indian Subcontinent have diminished alarmingly due to poisoning from diclofenac, a veterinary drug widely used to treat diseases in livestock. Research has shown that when the vultures feed on cattle carcasses, diclofenac will destroy their kidneys. In 2006, the Indian government announced a ban on the usage of diclofenac. Another drug, meloxicam, which seems to be a good substitute for diclofenac, is harmless to vultures. However, it is more expensive than diclofenac, and the ban has not had much effect, as it is largely ignored, probably by corrupt officials who benefit economically from the distribution of diclofenac.

Since 2016, re-introduction programmes have been instigated, primarily in nature reserves, where diclofenac is not present.

The African griffon species have also decreased dramatically in numbers in recent years, described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

Gyps bengalensis White-rumped vulture

Formerly, this bird was abundant in Pakistan, the Indian Peninsula, and Indochina, and in the 1980s the global population was estimated at several million individuals, making it the most abundant large bird of prey in the world. However, in the 1990s the population in India plummeted due to the widespread usage of diclofenac (see genus above), and in Indochina it disappeared due to the the lack of available carcasses. In 2021, it was believed that the world population was less than 6,000 adults.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of Bengal’. Strictly speaking, Bengal is the lowland around the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, but in 1788, when German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin (1748-1804) described the bird, the term ‘Bengal’ indicated a much larger portion of northern India.

White-rumped vulture, resting on the spire of a Hindu temple, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vultures take off from a tree, Sukkur, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vultures and one slender-billed vulture (Gyps tenuirostris, the pale bird), basking in the morning sun, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vulture, just about to land, Ambala, Haryana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vultures and dogs, fighting over the remains of a cow, Lahore, Pakistan. In the foreground, house crows (Corvus splendens) are waiting for tidbits. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vultures have eaten a dead water buffalo. Now workers of a certain cast are collecting the remains (bones and hide), taking them away on a bicycle. – Ambala, Haryana. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-rumped vultures, digesting after eating from a dead buffalo, Ambala, Haryana. Note the swelled gizzards. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These white-rumped vultures are fighting over a dead dog, beating their great wings, raising a cloud of dust. Meanwhile, the other vultures take advantage to eat from the carcass. – Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A white-rumped vulture is being teased by a house crow (Corvus splendens), which is pulling its wing feathers, Jaisalmer. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gyps indicus Indian vulture

This bird resembles the white-rumped vulture (above), but has paler upperwings, and the underwing coverts are not as white as in that species. It was formerly widely distributed in Peninsular India, but has largely disappeared due to the usage of diclofenac (see genus above).

Previously, under the name long-billed vulture, it was regarded as being widely distributed in the Indian Subcontinent and Indochina, but following genetic research, it has been split into two separate species, the Indian vulture and the slender-billed vulture (below). They are geographically separated, the Indian vulture restricted to central and western India, the slender-billed found north of the Ganges River, in a belt along the Himalayan foothills to Assam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia.

Indian vultures, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gyps tenuirostris Slender-billed vulture

As mentioned above, this bird was previously regarded as being conspecific with the Indian vulture. Like other vultures in India, it is critically endangered due to the widespread usage of diclofenac.

The specific name means ‘slender-billed’, derived from the Latin tenuis (‘slender’) and rostrum (‘bill’).

Symmetry. – Two slender-billed vultures dry their wings by spreading them out, facing the sun, near Pokhara, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliaeetus Sea-eagles, fish-eagles

A genus of 10 species, widely distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species in North America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hali (‘of the sea’) and aetos (‘eagle’). Despite the name ‘sea-eagle’, many of the species are living at freshwater areas inland. These species are termed ‘fish-eagles’.

Haliaeetus ichthyaetus Grey-headed fish-eagle

This species lives along rivers and lake shores, and in swamps. Adults are handsome birds, with brownish-grey head and breast, white belly, and a white tail with a broad black band at the tip.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek ikhthys (‘fish’) and aetos (‘eagle’).

Some authorities place this bird in the genus Ichthyophaga, together with the lesser fish-eagle (H. humilis).

Grey-headed fish-eagle, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliaeetus leucogaster White-bellied sea-eagle

This beautiful eagle is widely distributed, found along coasts from western India eastwards to southern China and the Philippines, southwards to Sri Lanka and Australia. It has declined in later years, but is still fairly common in many places.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and gaster (‘belly’).

Adult white-bellied sea-eagle, Bundala, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Immature white-bellied sea-eagle, Yala National Park, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliaeetus leucoryphus Pallas’s fish-eagle

This eagle breeds from Russia and Turkmenistan eastwards to northern China, southwards to India and Myanmar. It has declined drastically during the last 50 years, mainly due to increased usage of pesticides. It is listed as ‘endangered’ on the IUCN Red List of threatened species. Northern populations are migratory, wintering from northern India westwards to the Persian Gulf.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and koryphe (‘crown’).

The common name commemorates Prussian naturalist, ethnographer, and explorer Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811), who, in 1767, was invited by Catherine II of Russia to become a professor at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Between 1768 and 1774, he led an expedition to the Caspian Sea, the Ural and Altai Mountains, Lake Baikal, and the upper Amur River. His work from this expedition was published in 3 volumes 1771-1776, titled Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs (‘Journey through various provinces of the Russian Empire’).

In 1793 and 1794, Pallas led a second expedition to southern Russia, visiting the Crimea, the Black and Caspian Seas, and the Caucasus Mountains. His account of this expedition was published 1799-1801, titled Bemerkungen auf einer Reise in die Südlichen Statthalterschaften des Russischen Reichs (‘Notes from a trip to the southern lieutenancies of the Russian Empire’).

Nest of Pallas’s fish-eagle, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. The grass in the foreground is reed (Phragmites australis). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nests of Pallas’s fish-eagle, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. A full-grown young is seen in the nest in the lower picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pallas’s fish-eagle, Keoladeo National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliastur Kites

A small genus with two species, the widespread Brahminy kite (below), and the whistling kite (H. sphenurus) of Australia, New Caledonia, and New Guinea.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hali (‘of the sea’), and the Latin astur (‘hawk’).

Haliastur indus Brahminy kite

This common species is found at coasts and inland wetlands, from Pakistan eastwards to Vietnam and the Philippines, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, southwards to Sri Lanka and northern and eastern Australia.

The Brahminy kite is sacred to Hindus, reflected in the common name, which alludes to the highest Hindu cast, the Brahmins. In Hindu mythology, it is referred to as Garuda, the ‘king of birds’, and carrier of the mighty god Vishnu. In Tamil, it is known as Krishna parunthu (‘Krishna’s eagle’). Krishna is an avatar (incarnation) of Vishnu (more about this issue on the page Religion: Hinduism).

Brahminy kite, Minneriya Wewa Lake, near Sigiriya, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brahminy kites, Wirawila Wewa Lake, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Milvus Kites

A small genus with 3 or 4 species, erected in 1799 by French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825).

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the red kite (M. milvus).

Milvus migrans Black kite

A very widespread species, divided into 5 subspecies. It is found from central and southern Europe and northern Africa eastwards across Asia to Japan and Taiwan, and thence southwards to New Guinea and Australia.

The rather pale subspecies govinda is distributed from eastern Pakistan eastwards across warmer parts of India and Sri Lanka to Indochina and the Malay Peninsula. It is often observed in urban areas. In the higher parts of the Himalaya, it is replaced by subspecies lineatus, which is widespread in Central and East Asia.

The specific name is derived from the Latin migrare (‘to migrate’), alluding to the northernmost populations being migratory.

The subspecific name govinda alludes to the Hindu god Krishna, an avatar (incarnation) of the mighty god Vishnu. It is told that Krishna persuaded people who lived beneath the mountain Govardhana to worship the mountain instead of the rain god Indra, as he was of the opinion that the mountain, rather than the rain god, provided them with nourishment. Indra got furious, when the people no longer worshipped him and, as a punishment, sent torrential rain in order to drown people and cattle. However, Krishna protected them by raising the mountain, so that they could seek shelter beneath it. Indra acknowledged the superiority of Krishna, giving him the name Govinda, meaning ‘protector of cattle’.

Krishna and other Hindu gods are described in depth on the page Religion: Hinduism.

Black kite, ssp. govinda, and a feral pigeon (Columba livia), Udaipur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black kite, ssp. govinda, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Neophron percnopterus Egyptian vulture

This small vulture, the only member of the genus, has a very wide distribution, found from the Mediterranean eastwards across the Middle East to Kazakhstan and the Indian Subcontinent, and in the Sahel Zone of Africa, southwards to northern Tanzania. It also once had a resident population in Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, which is now considered extinct.

Three subspecies are currently recognized, the nominate northern and African birds, which have a mainly grey bill, Indian birds of subspecies ginginianus with a yellow bill, and finally a separate, larger subspecies, majorensis, in the eastern Canary Islands.

It lives in open areas, nesting on cliffs, less frequently in trees. Besides feeding on carcasses, it is often encountered at rubbish dumps, and it will also prey on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. It is among the few bird species known to use tools. Eggs of other birds, which are too large to break open with the bill, are broken by tossing stones onto them, using the bill.

This species is in decline over much of its range due to habitat destruction, hunting, poisoning, and collision with power lines.

The generic name stems from the Greek mythology. Neophron and Aegypius were young men and close friends, but it upset Neophron that his mother Timandra was having a love affair with Aegypius. To punish Aegypius, Neophron made advances towards Aegypius’ mother, Bulis. He succeeded and enticed Bulis into entering the dark chamber where his mother and Aegypius were soon to meet. Neophron then distracted his mother, tricking Aegypius into entering the chamber and sleeping with his own mother. When Bulis discovered the deception, she gouged out the eyes of her son before killing herself. Aegypius prayed for revenge, but Zeus, instead of helping him, changed both young men into vultures as a punishment.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek perknos (‘dark-coloured’) and pteron (‘wing’).

In Ancient Egypt, the bird was held sacred to the Moon God Isis, and its protection by Pharaonic law made it common in the streets, giving rise to the name pharaoh’s chicken.

On a hot spring day, an Egyptian vulture quenches its thirst at a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nisaetus Old World hawk-eagles

This genus of 10 species is found in tropical and subtropical Asia, from Pakistan eastwards to Japan and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia. They were earlier placed within the genus Spizaetus, which then consisted of Old World as well as New World eagles. However, genetic research has shown that the two groups are not closely related, and, consequently, the Old World species were moved to a separate genus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek, from the name Nisos, and aetos (‘eagle’). Nisos was a king of Megara, who possessed a purple lock of hair, which would protect him and his kingdom. According to one version of the legend, when King Minos of Crete besieged Megara, he tempted Nisos’s daughter Scylla with a golden necklace to betray and kill her father. In another version, she fell in love with Minos from a distance, and after cutting off her father’s purple lock, she presented it to Minos. However, Minos was disgusted with her act, calling her a disgrace. As Minos’s ships set sail, Scylla attempted to climb up one of them, but Nisos, who had turned into a sea eagle, attacked her, and she fell into the water and drowned. She was changed into a bird, possibly a heron, constantly pursued by Nisos.

Nisaetus cirrhatus Crested hawk-eagle

Divided into at least 5 subspecies, this eagle, also known as changeable hawk-eagle, is widely distributed, found from Pakistan and southern Nepal eastwards to Vietnam and the Philippines, southwards to Sri Lanka and Indonesia.

The endemic Sri Lankan race ceylanensis has a proportionally longer crest than the other subspecies, to 10 cm long.

The specific name is derived from the Latin cirrus (‘tendril’), thus ‘having tendrils’, alluding to the long, wavy crest, which may sometimes look twisted.

Formerly, this species was regarded as two separate species, the crested hawk-eagle (subspecies cirrhatus and ceylanensis of southern India and Sri Lanka), and the crestless changeable hawk-eagle (subspecies limnaeetus, andamanensis, and vanheurni). Some authorities retain this split.

Immature crested hawk-eagle, ssp. limneatus, Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crested hawk-eagle, ssp. ceylanensis, Yala National Park, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pernis Honey-buzzards

A small genus with 4 species, the crested honey-buzzard (below), the European honey-buzzard (P. apivorus), the barred honey-buzzard (P. celebensis), which lives in Sulawesi, and the Philippine honey-buzzard (P. steerei), which is restricted to the Philippines.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pernes, a word used by Greek scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) for a bird of prey. The common name refers to the fact that a significant part of the food of these birds consists of honey combs and wasp larvae.

Pernis ptilorhynchus Crested honey-buzzard

This bird is widely distributed in Asia, found from Kazakhstan and southern Siberia eastwards to north-eastern China and Japan, southwards to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘feathered bill’, derived from ptilon (‘feather’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’).

Crested honey-buzzard, ssp. ruficollis, resting in a silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sarcogyps calvus Red-headed vulture

This striking bird, previously known as king vulture, was once widespread in the Indian Peninsula and Indochina, but has declined drastically since the introduction of diclofenac in Indian cattle farming (see genus Gyps above). Today, it has a scattered occurrence in India, Myanmar, the Yunnan province, and Indochina.

It is the only member of the genus, but is quite closely related to the African lappet-faced vulture (Torgos tracheliotos), which is presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sarx (‘flesh’) and gyps (‘vulture’), whereas the specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bald’, alluding to the naked red head of the bird.

Red-headed vulture, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red-headed vulture, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spilornis Serpent-eagles

At least 6 species of these birds are found in forests of southern Asia. They often feed on snakes, hence their common name.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek spilos (‘spot’) and ornis (‘bird’), given in allusion to the white spots on breast and wings of the crested serpent-eagle (below).

Spilornis cheela Crested serpent-eagle

This eagle, comprising a large number of subspecies, is distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern Japan and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia. It is very variable, and some authorities propose treating several of the subspecies as separate species.

The specific name is derived from the Hindi word cheel (‘hawk’ or ‘kite’).

A dead tree in Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, serves as a lookout perch for this crested serpent-eagle. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is perched on a dead tree in Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spilornis elgini Andaman serpent-eagle

As its common name implies, this bird is endemic to the Andaman Islands. It has declined in later years. An alternative name is dark serpent-eagle.

The specific name honours James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin (1811-1863), who was Governor-General of India 1860-1863.

Immature Andaman serpent-eagle, Chidiyatappu, Andaman Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alaudidae Larks

This family contains 21 genera with about 100 species, distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species reaching the Americas, and Australia, respectively.

Alauda

A small genus with 4 species, distributed in Eurasia and northern Africa.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for lark.

Alauda gulgula Oriental skylark

This bird, divided into about 13 subspecies, is widely distributed, from Iran and Turkmenistan eastwards to Qinghai, Gansu, and south-western Inner Mongolia, southwards across the Pamir Mountains, the Tibetan plateau, and China to south India and Sri Lanka, Indochina, and the Philippines.

The specific name probably refers to the fine song of this species, derived from the Latin gula (‘throat’).

Oriental skylark, Bundala, near Hambantota, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ammomanes Desert larks

Following genetic research, this genus now contains only 3 species, whereas 4 others have been moved to other genera. The 3 remaining species are distributed from northern Africa eastwards to Kazakhstan and the Indian Peninsula.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ammos (‘sand’) and manes (‘passionately fond of’), from mania (‘passion’), alluding to the fact that these birds mainly live in sandy areas.

Ammomanes phoenicura Rufous-tailed lark

This species is endemic to Peninsular India. It has a scattered occurrence in Pakistan and southern Nepal, whereas it is widespread and common in India.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek phoinix (‘red’) and oura (‘tail’).

Rufous-tailed lark, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rufous-tailed lark, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eremopterix Sparrow-larks

These small larks, comprising 8 species, were named due to their resemblance to sparrows. They are also known as finch-larks. The genus is found in Africa, Madagascar, the southern part of Arabia, southern Iran, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eremos (‘desert’) and pteron (‘wing’), i.e. ‘birds of the desert’.

Eremopterix griseus Ashy-crowned sparrow-lark

This bird, also called ashy-crowned finch-lark, is widespread in all countries of the Indian Subcontinent, but is found nowhere else. It lives along sandy rivers and in shrubberies, grasslands, and farmland, but avoids the harshest desert areas, where its close relative, the black-crowned sparrow-lark (E. nigriceps), is common.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘grey’, alluding to the dominant colour of the bird.

Ashy-crowned sparrow-lark, Koshi Barrage, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ashy-crowned sparrow-lark, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mirafra Bush-larks

As of today, this genus contains about 24 species, distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, southern parts of Asia, and Australia. Following genetic studies, many other former members of the genus have been moved to other genera.

The etymology of the generic name is obscure.

Mirafra affinis Jerdon’s bush-lark

This bird is restricted to drier areas of Tamil Nadu, south-eastern India, and Sri Lanka. It is very similar to other Indian bush-larks, but generally has a more whitish underside. It was previously regarded as a subspecies of the Bengal bush-lark (M. assamica), reflected in the specific name, which is Latin, meaning ‘related to’ or ‘similar to’.

The common name commemorates British physician and naturalist Thomas Caverhill Jerdon (1811-1872), who described many birds species in India, several of which are named after him.

Singing Jerdon’s bush-lark, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alcedinidae Kingfishers

Kingfishers, comprising about 114 species of small to medium-sized, often brilliantly coloured birds, are characterized by having a large head, a long, sharp, pointed bill, and very short legs. As their name implies, most of these birds eat fish, although many species live away from water, eating mainly small invertebrates.

These birds are divided into 3 subfamilies: river kingfishers (Alcedininae), tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae), and water kingfishers (Cerylinae).

Alcedo

A small genus of 7 species of river kingfishers (Alcedininae), all feeding almost exclusively on fish. 4 species are restricted to warmer parts of Asia, 2 to sub-Saharan Africa. The seventh species is presented below.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for kingfisher.

Alcedo atthis Common kingfisher

This colourful bird has a very wide distribution, from western Europe across Asia to Sakhalin and Japan, and southwards to North Africa, Iraq, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and New Guinea.

There are three possible explanations to the specific name, all from the Greek mythology. 1) A handsome, richly dressed Indian youth, son of Limniace, nymph of the Ganges. 2) A beautiful young woman of Lesbos, favourite of the female poet Sappho (c. 630-570 B.C.). 3) An Athenian princess, daughter of King Cranaus and his wife Pedias. Jobling (2010) favours the Indian youth.

Common kingfisher, ssp. bengalensis, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ceryle rudis Pied kingfisher

This species, the only member of the genus, belongs to the water kingfishers (Cerylinae). It has a very wide distribution, found in sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, and in Asia, from Turkey eastwards across the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, and Indochina to south-eastern China.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kerylos, an unidentified bird mentioned by scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) and other authors. This bird was probably mythical, associated with the halkyon (see genus Halcyon below).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘rude’ or ‘uncultivated’. This strange name was applied by Swedish naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) who probably confused the Latin word hispida (‘kingfisher’) with hispidus (‘rough’ or ‘rude’).

Pied kingfisher, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hovering pied kingfisher, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon

A genus with 11 medium-sized kingfishers, of the subfamily tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae). They are distributed in warmer areas of Africa and Asia.

The generic name is associated with a bird of Greek legend, called Halcyon, generally thought to be the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). The Ancients believed that this bird made a floating nest in the Aegean Sea and had the power to calm the waves while brooding her eggs. Two weeks of calm weather were to be expected when the Halcyon was nesting, which took place around winter solstice. These Halcyon days were generally regarded as beginning on the 14th or 15th of December.

This belief in the bird’s power to calm the sea originated in a myth recorded by Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C. – c. 17 A.D.), known as Ovid. The story goes that Aeolus, ruler of the winds, had a daughter named Alcyone, who was married to Ceyx, the king of Thessaly. Ceyx drowned at sea, and in her grief, Alcyone threw herself into the waves. However, instead of drowning, she was transformed into a bird and carried to her husband by the wind. (Source: phrases.org.uk)

Halcyon pileata Black-capped kingfisher

A widespread species, found from India eastwards to China and Korea, southwards to Sri Lanka and Indonesia.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘capped’, derived from pileus (‘cap’).

Black-capped kingfisher, resting in a Casuarina tree, Bhitarkanika Wildlife Reserve, Maipura River delta, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon smyrnensis White-breasted kingfisher, white-throated kingfisher

This common bird is widely distributed in Asia, from Turkey and northern Arabia eastwards to eastern China and the Philippines, southwards to Sri Lanka and the Malay Peninsula.

The specific name refers to the Ancient Greek city of Smyrna, now called Izmir, in what is today western Turkey. Initially, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named this bird Alcedo smyrnensis, citing the work A natural history of birds : illustrated with a hundred and one copper plates, curiously engraven from the life (1731-1738), by English naturalist and illustrator Eleazar Albin (c. 1690-1742), which includes a description and an illustration of the Smirna kingfisher.

White-breasted kingfisher, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-breasted kingfisher, sitting on a stem of common reed (Phragmites australis), Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Todiramphus

This genus, comprising about 30 species of the subfamily tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae), is widely distributed, found from north-eastern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula eastwards across southern Asia and Australasia to Polynesia.

The generic name is derived from the genus name Todus (todies, small New World birds, resembling kingfishers), and Ancient Greek rhamphos (‘bill’), thus ‘with a bill like todies’.

Todiramphus chloris Collared kingfisher

Divided into about 14 subspecies, this bird is very widespread, found from the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula eastwards across southern Asia and Australasia to Micronesia. It lives in coastal areas and is partial to mangrove swamps.

The specific name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’).

Collared kingfisher, subspecies davisoni, resting in a mangrove tree, Havelock Island, Andaman Islands. This subspecies is endemic to the Andamans and the Coco Islands, a little further north. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

At present, this large worldwide family contains 43 genera with about 146 species.

Anas

Following genetic studies, this formerly very large genus has been divided into 7 genera, and today it contains 31 species.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for duck.

Anas acuta Northern pintail

Avoiding the harshest areas of the Arctic, this handsome duck breeds across the northern hemisphere, from Iceland, Norway, and Denmark eastwards to the Pacific, and also from Alaska and Canada southwards to central United States. It is a scarce breeding bird in central and eastern Europe, and in Turkey.

The winter months are spent in the southern half of North America, in Central America and the Caribbean, in the major part of Europe and the Middle East, in northern and eastern Africa, and in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, southern China, Taiwan, and the northern Philippines.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sharp-pointed’, like the common name alluding to the long, pointed tail.

A pair of northern pintail, Gadhi Sagar, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. The birds in the background, from left: Red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus), redshank (Tringa totanus), male pintail, white-tailed lapwing (Vanellus leucurus), and common teal (Anas crecca). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Silhouettes of feeding northern pintails, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anas poecilorhyncha Indian spot-billed duck

This bird was named for the yellow point of the otherwise black bill. It is distributed in the Indian Subcontinent and Indochina. Previously, birds found from south-eastern Siberia southwards through China and Japan to northern Indochina were regarded as a race of the Indian spot-billed duck, but are now considered a separate species by most authorities, named eastern spot-billed duck (A. zonorhyncha). The two species overlap in southern China and north-eastern Indochina, but research has shown that interbreeding very rarely takes place.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek poikilos (‘pied’ or ‘spotted’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’).

The eastern spot-billed duck is described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Indian spot-billed ducks, Surya Lake Reservoir, Rajkot, Gujarat. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spot-billed ducks, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anser Grey geese

A genus of 11 species, distributed in arctic and temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for goose.

Anser anser Greylag goose

As a breeding bird, this species is widely distributed in northern Eurasia, from Iceland and Britain across northern Europe and Central Asia to northern China, with a scattered occurrence in south-eastern Europe, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran.

In many countries, it now breeds in city parks, where it often becomes remarkably confiding – sometimes even showing a threatening attitude towards people (more about this issue on the page Animals: Urban animal life).

In winter, it occurs in Europe, north-western Africa, the Middle East, and from Afghanistan in a belt across the northern part of the Indian Subcontinent and Indochina to eastern China.

Greylag geese, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Aythya

A genus of 12 species, chiefly found in the Northern Hemisphere, with one species in New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, and on some Pacific islands, another one in New Zealand, and one in Madagascar. Two species are critically endangered, the East Asian Baer’s pochard (A. baeri) and Madagascar pochard (A. innotata).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aithyia, an unidentified seabird, mentioned by Greek grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th Century A.D.), and also by Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle (384-322 B.C.).

Aythya ferina Common pochard

This handsome duck is breeding in a vast area, from central and northern Europe eastwards across the taiga belt to south-eastern Siberia, Mongolia, and north-eastern China, southwards to Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. Most populations are migratory, wintering in Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, and from Pakistan and northern India eastwards across northern Indochina to southern China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the northern Philippines.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wild game’, derived from ferus (‘wild’).

Male common pochard, Lake Pichola, Udaipur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendrocygna Whistling-ducks

A genus of 8 species, distributed worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’) and kyknos (‘swan’), alluding to the fact that these ducks often breed in tree cavities, and to their fairly long neck. Several members have clear, whistling calls, which gave rise to the popular name.

Dendrocygna javanica Lesser whistling-duck

This species is widely distributed, found from Pakistan eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards to Sri Lanka and Indonesia. The Chinese populations are migratory.

The specific name refers to the Indonesian island Java. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

Lesser whistling-ducks, Yala National Park, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lesser whistling-ducks, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Netta

A small genus with 3 species, found from central and southern Europe eastwards to central Asia, in Africa, and in South America.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘duck’.

Netta rufina Red-crested pochard

The main breeding area of this beautiful duck is extreme southern Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Xinjiang, and western Mongolia, with a spotty occurrence in central and southern Europe, and Turkey. The winter months are spent in southern Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, and the Yunnan Province.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden-red’, derived from rufus (‘rufous’), alluding to the striking colour of the male’s head.

Red-crested pochard, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. The bird to the left is a northern shoveler (Spatula clypeata). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nettapus Pygmy geese

A small genus of 3 species of tiny ducks, the cotton pygmy goose (below), the African pygmy goose (N. auritus), which is widespread in Africa, and finally the green pygmy goose (N. pulchellus) of northern Australia and southern New Guinea.

Traditionally, these birds are called pygmy geese, although genetic research indicates that they are more closely related to dabbling ducks than to geese. The name alludes to the short, goose-like bill.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek netta (‘duck’) and pous (‘foot’), Apparently, German naturalist Johann Friedrich von Brandt (1802-1879), who erected the genus in 1836, regarded these birds as a kind of small geese due to their short bill, but also found that they possessed the feet and body of a duck.

Nettapus coromandelianus Cotton pygmy goose

This tiny duck is found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, in Indochina and Malaysia, a few places in Indonesia, and in New Guinea and north-eastern Australia. It is mainly sedentary, but disperses in winter.

The specific name refers to the Coromandel Coast, in present-day Karnataka. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there. The common name alludes to the dominant colour of the male.

Cotton pygmy goose, male and female, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sarkidiornis melanotos Knob-billed duck

This peculiar duck, with a large protuberance on the bill, is widely distributed in tropical wetlands in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, sub-Saharan Africa, and Madagascar. Previously, the very similar American comb duck, which lives in South America, was included in this species, but today many authorities regard it as a separate species, named S. sylvicola.

The generic name is probably derived from Ancient Greek sarx (‘meat’, or ‘body’) and ornis (‘bird’), maybe alluding to the compact body of the bird. The specific name is also derived from Ancient Greek, from melas (‘black’) and noton (‘back’).

Knob-billed ducks, resting in a tree, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. A bird is on its way up to the branch. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spatula Shovelers and allies

The ducks of this genus, comprising 10 species of shovelers and teals, were formerly placed in the genus Anas. The genus Spatula had originally been proposed in 1822 by German zoologist and lawyer Friedrich Boie (1789-1870), who described many new species and several new genera of birds. He and his brother Heinrich also described about 50 new species of reptiles.

The generic name is the Latin word for ‘spoon’ or ‘spatula’, alluding to the spatulate bill of shovelers.

Spatula clypeata Northern shoveler

As a breeding bird, this species is widely distributed across the northern hemisphere, avoiding the harshest areas of the Arctic. It is found from Iceland, the British Isles, Spain, and Morocco eastwards across the taiga belt to the Pacific, and also in Alaska and western North America, southwards almost to the Mexican border.

The winter months are spent in the southern half of North America, in Central America and the Caribbean, in the major part of Europe and the Middle East, in northern and eastern Africa, and in the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, southern China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the northern Philippines.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shield-bearing’, alluding to the broad and flat bill.

A huge gathering of northern shovelers, wigeons (Mareca penelope), and common teals (Anas crecca), Lake Chilka, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding male northern shoveler, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tadorna Shelducks

A small genus of 6 species of large ducks, distributed in Eurasia, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. One species, the crested shelduck (T. cristata) of Korea, may have gone extinct.

The generic name is from tadorne, the French name of the common shelduck (T. tadorna). It may have Celtic roots, meaning ‘pied waterfowl’. The English name, originally sheld duck, dates from around 1700, with a similar meaning.

Tadorna ferruginea Ruddy shelduck, Brahminy duck

The specific name of this colourful bird is Latin for ‘rusty’, referring to the plumage, which is mainly orange-brown. The head is paler, and tail and flight feathers are black, contrasting with the white wing-coverts. In India, this bird is known as Brahminy duck, likewise alluding to its colour, which resembles that of the robe of certain Brahmins (the uppermost caste of Hinduism).

This is essentially a Central Asian species, with breeding populations extending across the Middle East as far as south-eastern Europe, with isolated populations in north-western Africa and the highlands of Ethiopia. It is very common on the Tibetan Plateau.

It spends the winter months in the lowlands of northern Africa, Ethiopia, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, northern Indochina, and southern China.

Ruddy shelducks, resting on sand bars in the Rapti River, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ruddy shelducks, Rapti River. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A pair of ruddy shelduck, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. A redshank (Tringa totanus) and other birds are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anhingidae Darters

Darters, also called snakebirds due to their long, thin, flexible neck, are large water birds, comprising two or four species in the genus Anhinga, the sole genus of the family.

One or three species are found in the Old World. If only one species is acknowledged, it is called A. melanogaster. Most authorities, however, recognize three full species: Oriental (below), African (A. rufa), and Australasian (A. novaehollandiae). The American darter (A. anhinga) lives in the New World.

The generic name means ‘little head’ in the Tupi language of Brazil, referring to an evil spirit of the forests, the devil bird. (Source: G. Marcgrave 1648. Historiae rerum naturalium Brasiliae. Liber V)

Anhinga melanogaster Oriental darter

This species is resident in the Indian Subcontinent, Indochina, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and gaster (‘belly’).

Oriental darters, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oriental darters, drying their wings in the evening sun, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Swimming oriental darter, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This darter has just emerged from diving, creating concentric circles on the surface, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeidae Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Herons, comprising 18 genera with about 64 species, are long-legged and long-beaked, fish-eating water birds, distributed worldwide with the exception of the polar regions. Some species are called egrets, mainly birds with ornate plumes during the breeding season, whereas birds of the genera Botaurus, Ixobrychus, and Zebrilus are called bitterns.

Many members of the family are presented on the page Fishing.

Ardea

A genus with about 13 species of mainly large herons. Members are found almost worldwide.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons.

Ardea cinerea Grey heron

The grey heron is widely distributed, found in the major part of Eurasia, Africa, and Madagascar.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’.

Other pictures, depicting this bird, are shown on the pages Fishing, Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Animals: Urban animal life.

In America, it is replaced by the similar, slightly larger great blue heron (A. herodias), presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Grey heron, reflected in a pond, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. An oriental darter (Anhinga melanogaster) and a little cormorant (Microcarbo niger) are also seen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grey heron in evening light, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grey heron, blurred by morning fog, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea intermedia Yellow-billed egret, intermediate egret

This bird has a very wide distribution, found in sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, East and Southeast Asia, and Australia. In East Asia, it breeds as far north as South Korea and southern Japan. These northern birds are migratory, spending the winter in Taiwan, the Philippines, Indochina, and Indonesia.

The specific name refers to its size, intermediate between the great white egret (Ardea alba) and the little egret (Egretta garzetta, below), both of which are also white.

Some authorities place this bird in a separate genus, Mesophoyx.

Yellow-billed egrets, taking off from a swamp, Ambala, Haryana. The bird with black bill is a little egret (Egretta garzetta), and the large bird in the background is a great white egret (Ardea alba). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow-billed egrets, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardea purpurea Purple heron

This species is very widely distributed, breeding in Africa south of the Sahara, on Madagascar, in central and southern Europe, around the Mediterranean eastwards to Kazakhstan, from Pakistan eastwards to China and Siberian Ussuriland, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

Purple heron, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeola Pond herons

A genus of 6 species of small herons, most of which are found in tropical areas of Asia and Africa. One species, the squacco heron (A. ralloides), breeds in southern Europe and the Middle East, migrating to Africa in autumn.

Most of the year, the plumage of these birds is buff or brownish, making them extremely well camouflaged among various types of vegetation. When they take to flight, however, they are transformed as if by magic, when their brilliant white wings are displayed.

The generic name is from the Latin ardea (‘heron’) and –ola, a suffix denoting something diminutive, thus ‘small heron’.

Ardeola grayii Indian pond heron, paddy bird

This bird breeds from southern Iran eastwards to the Indian Subcontinent and Myanmar. It is a very common resident in the lowlands, but is easily overlooked in its drab winter plumage when standing at the edge of lakes, ponds, or paddy fields. It relies on its camouflage to a degree that it can be approached closely before taking to flight. This behaviour gave rise to the Hindi name andha bagla (‘blind heron’), as well as the Sri Lankan name kana koka (‘half-blind heron’).

Formerly, this bird was shot for meat. In his book A New Account of the East Indies, from 1744, Alexander Hamilton writes the following: “They have also store of wild fowl; but who have a mind to eat them must shoot them. Flamingoes are large and good meat. The paddy-bird is also good in their season.”

The specific name honours British zoologist John Edward Gray (1800-1875), who was keeper of zoology at the British Museum in London 1840-1874, until the natural history department was re-named the Natural History Museum.

Indian pond heron in morning light, walking on floating leaves of red waterlily (Nymphaea rubra), east of Colva, Goa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian pond heron, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Indian pond heron, resting on a rock in a river, Anshi National Park, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bubulcus ibis Cattle egret

This species is very widely distributed, found in most warmer areas of the world, only avoiding rain forests and desert areas. Originally, it was native to southern Spain and Portugal, the northern half of Africa, and across the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to Japan, and thence southwards to northern and eastern Australia.

However, in the late 1800s it began expanding its range into southern Africa, and in 1877 it was observed in northern South America, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean. By the 1930s, it had become established as a breeding bird in this area, rapidly spreading to North America, where it is now found as far north as southern Canada. In later years, it has also spread northwards in Europe.

As its name implies, it often follows cattle to snap grasshoppers and other small animals, flushed by the grazers. It is also often observed in newly ploughed fields. The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘cowherd’. The specific name is the classical Greek term for ibises. Why it was applied to the cattle egret is not clear.

Today, some authorities split the cattle egret into two species, the western (B. ibis) and the eastern (B. coromandus). Apart from minor differences, they are identical, so why this split was made, is incomprehensible. I prefer to regard all cattle egrets as a single species.

Many other pictures, depicting this bird, are shown on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Birds in the Himalaya.

Tree with breeding cattle egrets and little cormorants (Microcarbo niger), Aliwetawela, east of Badulla, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle egrets, illuminated by morning sunlight, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle egret, using the back of a water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) as a lookout post, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta Egrets

A genus of 12 small to medium-sized herons, the major part breeding in warmer areas around the globe. Most members have black legs with bright yellow toes, and many develop ornate plumes during the breeding season.

The generic name is derived from Provençal French aigrette, a diminutive of aigron (‘heron’).

Egretta garzetta Little egret

The little egret is found in most tropical and subtropical areas of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. In 1994, a small population was established on the Caribbean island Barbados, and the species has since spread to other Caribbean islands and to the Atlantic coast of the United States.

The specific name is the Italian name for the bird.

Little egret, feeding in the Rapti River, southern Nepal, and then taking off. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding little egret, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nycticorax Night-herons

Today, this genus contains only two species, the black-crowned night-heron (below), which is distributed almost worldwide in warmer areas, and the Nankeen, or rufous, night-heron (N. caledonicus), which is distributed in Australia, New Zealand, Java, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia, Palau, and the Solomon and Caroline Islands.

In historic times, 4 other species of the genus, which were all restricted to small islands in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, have gone extinct.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek nyktos (‘night’) and korax (‘raven’), referring to the mainly nocturnal feeding habits of these birds, and to their hoarse, raven-like call.

Nycticorax nycticorax Black-crowned night-heron

This smallish heron is common, found in most warmer parts of the world.

It figures in Japanese classical folklore, where it is called Goi-sagi, from goi (‘fifth rank’) and sagi (‘heron’). According to legend, the all-powerful Emperor Daigo (reigned 897-930 A.D.) ordered a vassal to capture a black-crowned night-heron. Upon hearing the imperial command, the heron submitted itself to capture. The emperor was pleased that the heron had confirmed his omnipotence over nature as well as man, whereupon he granted it the title ‘king of the herons’ and the position of fifth rank in his court, and released it unharmed. (Source: Jobling, 2010)

Black-crowned night-herons, resting in trees, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. The speckled individuals are immature birds. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-crowned night-herons, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bucerotidae True hornbills

These peculiar birds, comprising about 54-58 species, are distributed in tropical Asia and Africa. They vary greatly in size, from the small West African black dwarf hornbill (Horizocerus hartlaubi), which is 30 cm long and weighs only c. 100 grams, to the huge rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros) in Malaysia and Indonesia, growing to about 1.2 m long and weighing up to 5.9 kg.

The family name and the name of the type genus, Buceros, are derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘cow’) and keras (‘horn’), referring to a peculiar protuberance, or casque, on the bill of most species. Hornbills are very noisy, and the casque is probably a means to increase the volume of their call, which carries a long distance. The casque of males is larger than that of females.

A number of species are presented on the page Animals – Birds: Hornbills.

Ocyceros

This genus was established in 1873 by English naturalist Allan Octavian Hume (1829-1912), comprising 3 smaller hornbills in the Indian Subcontinent. Later, they were transferred to the genus Tockus, but have recently been moved back to Ocyceros.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oxys (‘sharp’ or ‘pointed’) and keras (‘horn’).

Ocyceros birostris Indian grey hornbill

This bird is widely distributed, from north-eastern Pakistan (around Lahore) eastwards along the Himalaya to western Bangladesh, southwards through almost the entire Indian Peninsula. It lives from the lowlands up to elevations around 700 m.

The male has a dark bill with a yellowish lower mandible, whereas that of the female is more yellow.

The specific name is derived from the Latin bi (two) and rostrum (‘bill’), alluding to the small protuberance on top of the bill, which, with a bit of imagination, looks like an extra bill.

Female Indian grey hornbill, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ocyceros griseus Malabar grey hornbill

An Indian endemic, found along the entire Western Ghats, from north of Mumbai to the southern tip of the peninsula. This species has no casque. The male has a reddish bill with a yellow tip, whereas that of the female is yellowish with black at the base of the lower mandible.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘grey’.

Male Malabar grey hornbill in morning light, Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary, Goa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burhinidae Thick-knees, stone-curlews

These birds comprise about 10 species in two genera, Burhinus and Esacus.

Esacus Stone-plovers

A small genus with only 2 species, distributed from southern Pakistan eastwards to Hainan, southwards to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, New Guinea, and northern Australia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aisakos. In Greek mythology, Aesacus was a prince of Troy, who was transformed into an unidentified bird. There are two versions of the myth. In one, Aesacus caused the death of the nymph Hesperie. He then committed suicide to share her days in eternity and was transformed into a long-necked, long-legged shorebird. In another version, he married Sterope. Mourning her premature death, he threw himself into the sea and was transformed into a cormorant. (Source: Jobling, 2010)

Esacus recurvirostris Great stone-plover

This large bird breeds along coasts, rivers, and lake shores, from Pakistan across the Indian Subcontinent and northern Indochina to Hainan.

The specific name is derived from the Latin recurvus (‘bent backwards’) and rostrum (‘bill’). The upper mandible is straight, whereas the lower one is curved, giving the impression that the bill is upturned.

Great stone-plover, Ramganga River, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Campephagidae Cuckooshrikes and allies

Members of this family are small to medium-sized passerines, found in subtropical and tropical regions of Africa, Asia, and New Guinea. The family has about 93 species, divided into 11 genera.

These birds are not closely related to cuckoos or shrikes. The name may refer to the grey colour of many cuckooshrikes, which makes them superficially resemble cuckoos.

Pericrocotus Minivets

A genus with about 15 species, found in forests from eastern Iran and Afghanistan eastwards across the Indian Subcontinent to China and Ussuriland in south-eastern Siberia, and thence southwards through Japan, Taiwan, Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia.

Several of the species are very colourful, the males being predominantly red and black, the females yellow and black. Some members of the genus are presented on the pages Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Birds in Bagan.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek peri (‘very’ or ‘all around’) and krokotos (‘golden-yellow’). The type specimen must have been a female!

The word minivet is of unknown origin.

Pericrocotus cinnamomeus Small minivet

This pretty bird is found in the Indian Subcontinent and Indochina, with a disjunct population in Java and Bali.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kinnamon (‘cinnamon’), thus ‘cinnamon-coloured’.

Male small minivet, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pericrocotus flammeus Orange minivet

This brilliantly coloured bird lives in dense forests, from western India and Sri Lanka eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Southeast Asia to Indonesia.

Formerly, it was regarded as a subspecies of the scarlet minivet, which is now called P. speciosus.

Male orange minivet, Anshi National Park, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Caprimulgidae Nightjars and nighthawks

This family of nocturnal or crepuscular birds is found on all continents except Antarctica. It is divided into 3 subfamilies, Caprimulginae (typical nightjars) with 14 genera and about 79 species, Eurostopodinae (eared nightjars) with 2 genera and 9 species, and Chordeilinae (nighthawks) with 3 genera and 10 species.

Caprimulgus Typical nightjars

A large genus with about 37 species, found in Eurasia, Africa, and Australia.

In the old days, these birds were often called goatsuckers, as it was believed that they would suck milk from goats at night. This belief dates back to Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.), who called these birds caprimulgus, derived from capra (‘she-goat’) and mulgere (‘to milk’). He wrote: “Those called goat-suckers, which resemble a rather large blackbird, are night thieves. They enter the shepherds’ stalls and fly to the goats’ udders in order to suck their milk, which injures the udder and makes it perish, and the goats they have milked in this way gradually go blind.”

In 1758, the name caprimulgus was adopted by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), when he named the European nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. In German, nightjars are still called Ziegenmelker (‘goat-milkers’).

Caprimulgus mahrattensis Sykes’s nightjar

This bird has a rather limited distribution, found in eastern Iran, southern Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north-western India.

The specific name refers to Mahratta, today called Maharashtra, in central India. This is odd, as the species is not supposed to occur so far south. The common name commemorates British colonel and naturalist William Henry Sykes (1790-1872), who served in India.

Dead Sykes’s nightjar, Haleji Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh, Pakistan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Charadriidae Plovers and lapwings

This family of small to medium-sized waders comprise about 10 genera with about 65 species. They are distributed almost worldwide, the vast majority near wetlands.

Pluvialis Golden plovers

Formerly, it was believed that there was only a single species of golden plover, P. apricaria, which was divided into three subspecies. However, these subspecies have since been upgraded to separate species, the Eurasian golden plover (P. apricaria), which breeds in tundra from Iceland eastwards to central Siberia, the Pacific golden plover (below), and the American golden plover (P. dominica), which breeds in the northernmost regions of North America.

The only other member of the genus, the grey plover (P. squatarola), is presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

The generic name is from the Latin pluvia (‘rain’). An old word said that when golden plovers flocked, it would mean imminent rain.

Pluvialis fulva Pacific golden plover

This species is found along the Siberian coast, from the Jamal Peninsula eastwards to the Chukotka Peninsula and extreme western Alaska.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tawny’ or ‘yellowish-brown’, referring to the breeding plumage.

Pacific golden plover, Long Wheeler Island, Bhitarkanika Wildlife Reserve, Maipura River delta, Odisha. The plants are young mangrove trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vanellus Lapwings

This genus contains 24 species of medium-sized waders, distributed in most parts of the globe.

The generic name is Latin, diminutive of vannus (‘winnowing fan’), referring to the whirring sound, produced by the wings of the northern lapwing (V. vanellus) during courtship display.

The common name is derived from Old English hleapewince, of hleapan (‘to leap’) and wince (‘move rapidly’), likewise alluding to the courtship display of the northern lapwing, when the male twists and turns at a tremendous speed over the meadows.

Vanellus duvaucelii River lapwing

As its name implies, this bird lives along rivers, stony as well as sandy, in the northern half of India and in Indochina.

The specific name commemorates French naturalist and explorer Alfred Duvaucel (1793-1824), who died in India, only 31 years old. Rumours had it that he was killed by a tiger.

River lapwing, Ramganga River, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vanellus indicus Red-wattled lapwing

This common bird was named for the red wattles of bare skin, stretching from the eyes to the base of the bill. Its distinctive call is rendered as Did-he-do-it?, or, when the bird is excited: Did-did-did-he-do-it?

It is distributed from south-eastern Turkey through Iraq and Iran to the Indian Subcontinent and Indochina.

In Sinhalese, the bird is called kirala. It figures in the title of a novel, Call of the kirala, by Sri Lankan author James Shedden-Goonewardene (1921-1997), Hansa Publishers Limited, Colombo, 1971. Incidentally, his name is spelled Goonawardene on the cover of the book.

Red-wattled lapwing, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red-wattled lapwings in courtship display, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This red-wattled lapwing is feeding along the shore of a stony waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vanellus malabaricus Yellow-wattled lapwing

This bird is easily identified by the hanging yellow wattles around the bill. It is endemic to the Indian Subcontinent, living in rather dry, grassy plains.

The specific name refers to the Malabar Coast of south-western India, where the type specimen was collected.

Yellow-wattled lapwing, Zainabad, Gujarat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chloropseidae Leafbirds

This family consists of a single genus, Chloropsis, with 13 species of attractive bright green or turquoise passerines, distributed from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China, and thence southwards through Indochina and the Philippines to Indonesia.

The family and generic names are derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’) and opsis (‘appearance’).

Chloropsis jerdoni Jerdon’s leafbird

This colourful bird is widely distributed in the Indian Subcontinent. The male differs from the female by having a black throat and a blue moustachial stripe.

Previously, Jerdon’s leafbird was regarded as a subspecies of the more widespread blue-winged leafbird (then called C. cochinchinensis). However, it differs in morphology, lacking the blue flight feathers of that species. Following recent genetic research, C. cochinchinensis has been split into 3 separate species.

The specific name commemorates British physician and naturalist Thomas Caverhill Jerdon (1811-1872), who described many birds species in India, several of which are named after him.

This male Jerdon’s leafbird was caught in a mistnet to be ringed, near Mysore, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ciconiidae Storks

These large birds, comprising 6 genera with 19 species, are found in most parts of the world, being absent from the polar regions and the major parts of North America and Australia.

The word stork originates in Ancient Germanic sturkoz.

Anastomus Open-billed storks

A small genus with only two species of striking birds, characterized by their gaping bill, an adaptation to feed on their preferred food, molluscs. The black African openbill (A. lamelligerus) is restricted to Africa south of the Sahara, and Madagascar, whereas the predominantly grey Asian openbill (below) is found in Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek anastomoo (‘to furnish with a mouth’), in this connection meaning ‘with mouth wide open’.

Anastomus oscitans Asian open-billed stork

This species is restricted to wetlands in the Indian Subcontinent and the southern part of Indochina. Outside the breeding season, these birds move much around in response to newly formed wetlands after rain.

When the British were ruling in India, hunters often shot the openbill for meat, calling it the ‘beef-steak bird’, a term that was also used for the woolly-necked stork (below).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘yawning’, derived from oscitare (‘to yawn’), naturally alluding to the beak.

Breeding colony of Asian open-billed stork, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. Adult birds have reddish legs. Immature birds have grey legs, and, at this age, their bill is not yet gaping. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young open-billed stork, spreading its wings, Keoladeo National Park. To the left black-headed ibises (Threskiornis melanocephalus) and little cormorants (Microcarbo niger). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One adult open-billed stork and several immature birds in a breeding colony, Maipura River, Bhitarkanika Wildlife Reserve, Odisha. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding adult open-billed stork, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This open-billed stork is scratching its face, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Open-billed stork, taking off, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ciconia Typical storks

A genus of 7 species, distributed in Africa, Eurasia, and South America.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for storks.

Ciconia episcopus Asian woolly-necked stork

Today, this bird, previously known as white-necked stork, is restricted to Asian wetlands, found from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards across Indochina to the Philippines, and thence southwards to Indonesia.

Formerly, birds in Africa were regarded as a subspecies, microscelis, but today a number of authorities consider these birds a separate species, the African woolly-necked stork (C. microscelis), based entirely on geographical separation, which is odd, as many other bird species are found in tropical areas of the two continents, without being regarded as separate species.