Birds in Costa Rica and Guatemala

Male red-legged honeycreeper (Cyanerpes cyaneus), feeding in flowers of blue porterweed (Stachytarpheta frantzii), Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boat-billed heron (Cochlearius cochlearius), Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

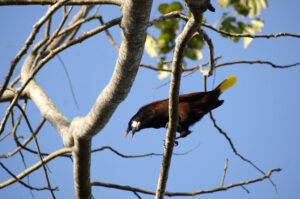

Montezuma oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma), preening its bright yellow tail feathers, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This page deals with a selection of birds, which I encountered during a 7 week long stay in Guatemala October-December 1998, and a one month long stay in Costa Rica January-February 2012.

Families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order. The nomenclature largely follows the IOC World Bird List (worldbirdnames.org). Information about etymology is often based on J.A. Jobling, 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London.

In case you find any errors, I would be grateful to receive an email. You may use the address at the bottom of this page.

Accipitridae Hawks, eagles, and allies

A huge family, comprising about 66 genera and c. 250 species of small to large raptors, distributed worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica.

Buteo Buzzards

A genus of about 28 species, distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. In the Old World, these birds are known as buzzards, whereas the word hawk is often used in North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common buzzard (Buteo buteo).

Buteo magnirostris Roadside hawk

This smallish buzzard, comprising 12 subspecies, is one of the commonest raptors in Latin America, living in a wide variety of habitats, from eastern and southern Mexico southwards to South America east of the Andes, as far south as northern Argentina.

The specific name is derived from the Latin magnus (‘large’) and rostrum (‘bill’).

Roadside hawk in evening light, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Roadside hawk, Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buteogallus

A genus with 9 species, found from southern Arizona southwards to Argentina.

The generic name was introduced in 1830 by French surgeon and naturalist René-Primevère Lesson (1794-1849), for the rufous crab hawk (B. aequinoctialis). It is a combination of the genus names Buteo (buzzards) and Gallus (junglefowl). Apparently, he found that this bird looked like a mixture of the two.

Buteogallus anthracinus Common black-hawk

This species breeds from southern Arizona southwards through Mexico and Central America to northern South America, eastwards to Guayana, southwards to Ecuador. It is also found on Trinidad & Tobago, and the Lesser Antilles. It is mainly coastal, living in mangrove swamps and along estuaries. However, some inland populations also exist, including that of north-western Mexico and Arizona.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘charcoal’, alluding to the colour of the bird.

Common black-hawks, Corcovado National Park, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. One is perched in a coconut palm, while another is feeding among coastal rocks. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alcedinidae Kingfishers

Kingfishers, comprising about 114 species of small to medium-sized, often brilliantly coloured birds, are characterized by having a large head, a long, sharp, pointed bill, and very short legs. As their name implies, most of these birds eat fish, although many species live away from water, eating mainly small invertebrates.

These birds are divided into 3 subfamilies: river kingfishers (Alcedininae), tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae), and water kingfishers (Cerylinae).

Chloroceryle Green kingfishers

This small genus contains 4 species, distributed from southern Texas southwards to central Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’), combined with the generic name Ceryle, derived from Ancient Greek kerylos, an unidentified, probably mythical bird, mentioned by scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) and other authors.

Chloroceryle amazona Amazon kingfisher

This bird, which belongs to subfamily Cerylinae, is distributed in a huge area, from southern Mexico southwards to northern Argentina. Head and back are dark bronzy green, divided by a white collar. Adult males have a white underside with a large rufous patch in the centre, and dark green sides. Adult females lack the rufous breast, but the green of the sides extends across the breast almost to the centre.

Male Amazon kingfisher, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. Judging from the many dung streaks, this dead trunk is often used as a perch by the bird. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

At present, this large worldwide family contains 43 genera with about 146 species.

Dendrocygna Whistling-ducks

A genus of 8 species, distributed worldwide in tropical and subtropical areas.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’) and kyknos (‘swan’), alluding to the fact that these ducks often breed in tree cavities, and to their fairly long neck. Several members have clear, whistling calls, which gave rise to the popular name.

Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied whistling-duck

This striking duck is widespread and quite common, found from central United States southwards to northern Argentina. Birds have strayed as far north as southern Canada. It is estimated that the total population is somewhere between one and two million, and it is increasing.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the autumn’. What it refers to is not clear.

Swamp with many black-bellied whistling-ducks and a single roseate spoonbill (Platalea ajaja), Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anhingidae Darters

Darters, also called snakebirds due to their long, thin, flexible neck, are large water birds, comprising two or four species in the genus Anhinga, the sole genus of the family. The American darter (below), often called anhinga, lives in the New World.

One or three species are found in the Old World. If only one species is acknowledged, it is called A. melanogaster. Most authorities, however, recognize three full species: Oriental (A. melanogaster), African (A. rufa), and Australasian (A. novaehollandiae).

The generic name means ‘little head’ in the Tupi language of Brazil, referring to an evil spirit of the forests, the devil bird. (Source: G. Marcgrave 1648. Historiae rerum naturalium Brasiliae. Liber V)

Anhinga anhinga American darter

This bird lives in swamps in warmer areas, found in a coastal belt from southern South Carolina southwards to Texas, on Cuba and surrounding islands, along both coasts of Mexico and Central America, and in South America east of the Andes, southwards to northern Argentina and Uruguay. Some birds stray far from the breeding area. In the U.S., the species has been observed as far north as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Incubating American darter on its flimsy nest, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeidae Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Herons, comprising 18 genera with about 64 species, are long-legged and long-beaked, fish-eating water birds, distributed worldwide with the exception of the polar regions. Some species are called egrets, mainly birds with ornate plumes during the breeding season, whereas birds of the genera Botaurus, Ixobrychus, and Zebrilus are called bitterns.

Many members of the family are presented on the pages Fishing, and Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Ardea

A genus with about 13 species of mainly large herons, distributed almost worldwide.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons.

Ardea alba Great white egret

A large heron with an almost global distribution, found in Europe, Africa, most of Asia, Australia, and the Americas. Traditionally, it was placed in the genus Egretta (below), mainly due to its white plumage. Some authorities have also placed it in a separate genus, Casmerodius. However, it shows many affinities to large herons in the genus Ardea.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’.

Great white egret in morning light, Monterrico, Guatemala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Butorides

Most authorities recognize 3 small herons of this genus as separate species, the green heron (below), the widespread striated heron (B. striata), and the lava heron (B. sundevalli), which is endemic to the Galapagos Islands. Others regard them as being conspecific.

The generic name is derived from Middle English botor (‘bittern’), and Ancient Greek oides (‘resembling’).

Butorides virescens Green heron

This small heron is breeding in the eastern half of the United States and extreme southern Canada, and also along the Pacific coast, from British Columbia southwards. In Mexico and Central America, it is found along both coasts, eastwards to Panama. It is also a resident in the entire Caribbean. Northern populations are migratory, wintering in southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘greenish’.

Green heron, Monterrico, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Green heron, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cochlearius cochlearius Boat-billed heron

This bird, the only member of the genus, was named for its flat bill, the generic and specific names derived from the Latin cochlear (‘a spoon’), originally from Ancient Greek kokhlias (‘a snail’s shell’).

It is distributed from eastern and southern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and southern Brazil.

Boat-billed heron, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta Egrets

A genus of 12 small to medium-sized herons, the major part breeding in warmer areas around the globe. Most members have black legs with bright yellow toes, and many develop ornate plumes during the breeding season.

The generic name is derived from Provençal French aigrette, a diminutive of aigron (‘heron’).

Egretta caerulea Little blue heron

This small heron is widely distributed in coastal areas in the southern part of North America and along the east coast to Maine, in Central America, and in South America southwards to Peru and southern Brazil. It lives in freshwater as well as brackish water. Northern populations are migratory, wintering in the Caribbean and Central America. After the breeding season, birds may stray northwards to southern Canada, southwards to Uruguay.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘blue’.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Little blue heron, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Egretta thula Snowy egret

A small heron, named for its snow-white plumage. It is very similar to the Old World little egret (E. garzetta).

It breeds along both coasts, from Oregon and Massachusetts southwards to Central America, in the Caribbean, and in South America, southwards to central Chile and Argentina. It is also found in many scattered locations in the interior United States, where populations are migratory, wintering mainly in Mexico and Central America.

In 1782, the specific name was mistakenly applied to this bird by Chilean Jesuit priest and naturalist Juan Ignacio Molina (1740-1829), who didn’t realize that in fact thula was the local Mapuduncun name for the black-necked swan (Cygnus melancoryphus).

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Snowy egret, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nyctanassa violacea Yellow-crowned night-heron

This beautiful heron breeds from eastern United States southwards through the Caribbean and Mexico to coastal areas of South America, as far south as northern Peru and southern Brazil. Northern populations are migratory.

It is the only living member of the genus, as another member, the Bermuda night-heron (N. carcinocatactes), which was restricted to Bermuda, is extinct.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek nyx (‘night’), genitive nyktos (‘of the night’), and anassa (‘queen’), referring to its nocturnal habits, and its beauty.

Yellow-crowned night-heron, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tigrisoma Tiger-herons

A small genus of 3 species, found from Mexico southwards to Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tigris (‘tiger’) and soma (‘body’), alluding to the striped plumage of these birds.

Tigrisoma mexicanum Bare-throated tiger-heron

This bird is found in coastal areas along both coasts, from northern Mexico southwards to extreme north-western Columbia.

Bare-throated tiger-heron, searching for food in a tidal pool, Corcovado National Park, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burhinidae Thick-knees, stone-curlews

These birds comprise about 10 species in two genera, Burhinus and Esacus.

Burhinus Thick-knees, stone-curlews

This genus of 8 species is widely distributed, from southern Europe across the Middle East to the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia, and thence southwards through Indonesia to Australia, in Africa, in Central America and northern South America, and along coastal Ecuador and Peru. Most species live in dry habitats.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek bous (‘ox’) and ‘rhinos’ (‘nose’, or, in this connection, ‘bill’), alluding to the large bill of these birds. The name thick-knee refers to the swelling of the leg joint.

Burhinus bistriatus Double-striped thick-knee

This striking bird has a rather spotty distribution, occurring from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to western Costa Rica, in northern Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, and extreme northern Brazil, and in the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘double-striped’, referring to the bird having two stripes from the crown to the back of the head.

Double-striped thick-knee, Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Caprimulgidae Nightjars and nighthawks

This family of nocturnal or crepuscular birds is found on all continents except Antarctica. It is divided into 3 subfamilies, Caprimulginae (typical nightjars) with 14 genera and about 79 species, Eurostopodinae (eared nightjars) with 2 genera and 9 species, and Chordeilinae (nighthawks) with 3 genera and 10 species.

In the old days, these birds were often called goatsuckers, as it was believed that they would suck milk from goats at night. This belief dates back to Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.), who called these birds caprimulgus, derived from capra (‘she-goat’) and mulgere (‘to milk’). In 1758, this name was adopted by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), when he named the European nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. In German, nightjars are still called Ziegenmelker (‘goat-milkers’).

Chordeiles Nighthawks

A genus with 6 species of New World birds, found from southern Alaska and central Canada southwards to northern Argentina.

The generic name is very poetic, derived from Ancient Greek khoreia, a kind of dance with music, and deile (‘evening’). This name was introduced in 1832 by English naturalist and artist William Swainson (1789-1855), who brought back to England a huge collection from Brazil and other places, including over 20,000 insects, 1,200 species of plants, drawings of 120 species of fish, and about 760 bird skins.

While Swainson was generally regarded as having some expertise in zoology, his botanical career turned out to be disastrous. William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), the first director of the famous Kew Botanical Gardens, wrote about him: “In my life I think I never read such a series of trash and nonsense. There is a man who left this country with the character of a first rate naturalist (though with many eccentricities), and of a very first-rate natural history artist, and he goes to Australia and takes up the subject of botany, of which he is as ignorant as a goose.”

Chordeiles acutipennis Lesser nighthawk

This species occurs from south-western United States southwards through Mexico and Central America to northern Chile, Bolivia, and Brazil. The northernmost populations are migratory.

The specific name is derived from the Latin acutus (‘sharp’) and penna (‘flight feather’), although penna may also mean ‘wing’, as a symbol of speed.

Feeding lesser nighthawk and Moon, Monterrico, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cathartidae New World vultures

This family contains 5 genera with 5 species of vultures and 2 species of condors, distributed from southern Canada southwards to southern South America.

Coragyps atratus Black vulture

This common species, the only member of the genus, is widely distributed in America, from southern United States southwards to central Chile and Uruguay. In eastern U.S., it has been observed as far north as New Jersey and Indiana.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek korax (‘raven’) and gyps (‘vulture’), the former alluding to the raven-black plumage of this bird. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘clothed in mourning’, derived from ater (‘black’). Very black indeed!

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Black vulture, resting atop a Mayan ruin, known as North Acropolis, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black vultures, gathered in a night roosting tree, Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Preening black vulture, Cahuita. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black vultures, feeding on a car-killed raccoon (Procyon lotor), Cahuita. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Charadriidae Plovers and lapwings

This family of small to medium-sized waders comprise about 10 genera with about 65 species. They are distributed almost worldwide, the vast majority near wetlands.

Charadrius Ringed plovers, dotterels

These birds, comprising about 32 species of mainly small waders, are found throughout the world, usually in wetlands.

The generic name is the Latin word for a yellowish bird, mentioned in Biblia Vulgata, a Latin translation of the Bible from the late 4th Century. The word was derived from Ancient Greek kharadrios, a bird found in river valleys, from kharadra (‘ravine’).

Charadrius collaris Collared plover

This small wader is very widespread, found along coasts and riverbanks, from central Mexico southwards to the major part of South America, as far south as central Chile and Argentina.

Collared plover on a sandy beach, Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. The plant with large leaves is beach morning-glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae), described on the page Plants: Morning-glories and bindweeds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Columbidae Pigeons and doves

A large family with about 50 genera and c. 345 species. The word pigeon generally denotes larger species, dove smaller species. These birds are found on all continents except Antarctica.

Columbina

This genus of small doves, comprising 9 species, ranges from southern United States southwards to the major part of South America.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘dove-like’, derived from columba (‘dove’).

Columbina minuta Plain-breasted ground-dove

This tiny dove is found from southern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and southern Brazil. It is absent from the Andes and most of the Amazon Basin.

The common name alludes to the bird lacking the scaled appearance of the common ground-dove (C. passerina).

Plain-breasted ground-doves, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corvidae Crows and allies

This almost cosmopolitan family contains 24 genera with more than 120 species of ravens, crows, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs, nutcrackers, and others.

A large number of species are described on the page Animals – Birds: Corvids.

Calocitta Magpie-jays

A small genus of two species, found in Mexico, Guatemala, and Costa Rica.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’), and kitta, which originally was the name of the jay (Garrulus glandarius), but in this connection means ‘magpie’.

Calocitta formosa White-throated magpie-jay

A large and long-tailed species, with a total length of up to 56 cm, distributed in dry thorn forest and semi-humid woodland along the Pacific coast from Jalisco, Mexico to Guanacaste, Costa Rica, Costa Rica. It usually lives below an elevation of 800 m, but may occasionally be encountered up to 1,250 m.

This noisy bird often travels about in flocks. The specific name is Latin, like the generic name meaning ‘beautiful’. Well, it is indeed a very pretty bird, with a prominent curved black-and-white crest on the crown, blue wings and upper tail, and a pure white underside with a thin dark-blue line, running from the nape across the upper breast.

White-throated magpie-jays, Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. The birds in the bottom picture are drinking from a sink in a campground. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Psilorhinus morio Brown jay

The only member of the genus, this jay is quite common in a rather narrow belt along the Mexican Gulf, from the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas southwards and eastwards to western Panama.

The plumage varies geographically. Northern birds are dark brown on the upper parts, lighter brown on the underparts (hence the name of the bird), whereas southern birds are white-bellied, with white tips to the outer tail feathers. Intermediate forms occur around the Vera Cruz area in Mexico.

Adults have black bills, legs, and feet. It has a naked inflatable sac on the chest, which presumably regulates its body temperature, but it also produces strange clicking or hiccuping sounds, when the bird is calling.

Superficially, birds of southern populations resemble the common magpie (Pica pica), but are slightly smaller, with a shorter tail, but a larger bill.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek psilos (‘tall’ or ‘thin’) and rhinos (‘nose’), presumably alluding to the compressed, tall bill of this bird. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek moros (‘fool’), maybe referring to the strange sounds that the bird emits.

Brown jay preening, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cracidae Guans and allies

This family contains 11 genera with 57 species of rather chicken-like birds, which, however, are more closely related to the Australasian megapodes (Megapodiidae). They are mainly found in Central and South America, with one species reaching Texas, and two species living on Trinidad & Tobago.

Penelope Guans

A genus of 16 species, found from central Mexico southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The generic name was given in 1786 without explanation by German naturalist Blasius Merrem (1761-1824). It may be derived from the Latin pene (‘almost’) and Ancient Greek lophos (‘crest’), alluding to the partial crest of the Marail guan (P. marail), or it may refer to Penelope, a princess in Greek mythology, the unfaithful wife of King Ulysses of Ithaca.

The common name is a Spanish corruption of the Kuna name for these birds, kwama.

Penelope purpurascens Crested guan

This large bird, with a length to 90 cm and a weight up to 1,800 g, lives in lowlands forests, from eastern and southern Mexico eastwards to Columbia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. It has declined in later years due to habitat destruction.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘purplish’.

Crested guan, Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crested guan, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cuculidae Cuckoos

Members of this family, which contains 6 subfamilies with 147 species in 33 genera, are found on all continents, except Antarctica. The majority lives in tropical or subtropical environments, whereas those living in temperate areas migrate in winter. Most members of the family are nest parasites, laying eggs in nests of other birds.

Crotophaga Anis

A genus of 3 species, found from southern United States and the Bahamas southwards through Mexico and the Caribbean to northern Argentina and Uruguay.

These large, black birds are characterized by their huge, compressed bill and the long tail. They are very gregarious, mostly observed in noisy groups. Unlike most cuckoos, they are not brood parasites, but nest communally, several pairs building a nest, in which the females lay their eggs and then share incubation and feeding the young.

The generic name, introduced in 1758 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), is derived from Ancient Greek kroton (‘tick’) and ephagon (‘to eat’). Linnaeus cited Irish physician and naturalist Patrick Browne (1720-1790), who, in his The Civil and Natural History of Jamaica (1756) used the name Crotophaga, remarking that smooth-billed anis “live chiefly upon ticks and other small vermin, and may be frequently seen jumping about on cows and oxen in the fields.”

The common name was possibly the name of these birds in the Brazilian Tupi language.

Crotophaga ani Smooth-billed ani

This species is distributed from southern Florida and the Bahamas southwards through the Caribbean to Costa Rica, Panama, and South America east of the Andes, southwards to northern Argentina and Uruguay.

A common bird, living in shrubberies and open country, including farmland. It is increasing, greatly benefited from the ubiquitous deforestation.

Smooth-billed ani, spreading its wings in the morning sun, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crotophaga sulcirostris Groove-billed ani

This bird closely resembles the previous species, but may be identified by the horisontal grooves on the bill. It is distributed from south-estern Texas and north-western Mexico southwards to Columbia, Venezuela, and Guayana, and in coastal Ecuador and Peru. There are also isolated populations in northern Chile, Bolivia, and north-western Argentina.

The specific name is derived from the Latin sulcus (‘furrow’) and rostrum (‘bill’).

Groove-billed ani, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Falconidae Falcons and caracaras

This family, counting about 60 species, is divided into 3 subfamilies, Herpetotherinae (laughing falcon and forest falcons), Polyborinae (caracaras and Spiziapteryx), and Falconinae (typical falcons and falconets).

Genetic research has shown that these birds are not closely related to raptors of the family Accipitridae. Their similar feeding habits are an example of convergent evolution.

Caracara plancus Crested caracara

This is the only living member of the genus, as the Guadalupe caracara (C. lutosa), which was native to Guadalupe Island off the west coast of Baja California, was hunted to extinction by 1906.

It has a huge distribution area, found from southern Arizona, Texas, Florida, and Cuba southwards through Mexico and Central America to Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Islands. It is divided into two subspecies, plancus, which is found from Peru and northern Brazil southwards, and the northern cheriway. For a period of time, they were regarded as separate species.

As opposed to typical falcons, this bird often walks on the ground, searching for prey.

The generic name is the Brazilian Tupi name of this bird, meaning ‘shrieker’, alluding to its call, a rattling sound, similar to running a stick along a fence. The specific name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek plangos (‘eagle’), alluding to its eagle-like appearance.

Crested caracara, northern subspecies cheriway, with nesting material, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herpetotheres cachinnans Laughing falcon

This striking bird, the only member of the genus, is widely distributed, found from northern Mexico southwards to the major part of South America east of the Andes, as far south as Paraguay and extreme north-eastern Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek herpeton (‘reptile’) and theras (‘hunter’), alluding to its favourite food. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘laughing’, referring to its loud call.

Laughing falcon, resting in a dead tree with many epiphytes, El Castillo, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Milvago Caracaras

A small genus of 2 species, the yellow-headed caracara (below), and the Chimango caracara (M. chimango), which is found in southern South America.

The generic name is derived from the Latin milvus (‘kite’) and the suffix ago (‘resembling’).

Milvago chimachima Yellow-headed caracara

This bird is resident from western Costa Rica southwards to northern Argentina, and also occurs on several southern Caribbean islands. It lives in various habitats, including savanna, swamps, and forest edges, and it may also scavenge in cities.

The specific name is a local Argentinian onomatopoeia (a word imitating the call of this bird).

Yellow-headed caracara, Rio Tárcoles, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow-headed caracara, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fregatidae Frigatebirds

This family contains only a single genus, Fregata, comprising 5 species of large seabirds with a long, deeply forked tail and a long hooked bill. The wings are very long, with a span up to 2.3 m. Males have a large red gular pouch, which they inflate during the breeding season to attract females. Females can be identified by their white belly. These birds are kleptoparasites, as they often rob other seabirds of their food, and they may also grab seabird chicks from nests.

When describing a specimen in 1667, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste du Tertre (1610-1687) called it la frégate, which was French mariners’ name for the bird. A frigate is a type of fast warship, and the name may have been inspired by the fast and elegant flight of these birds. The English term frigatebird was first used in 1738 by English naturalist and illustrator Eleazar Albin (c. 1690-1742) in his book A Natural History of the Birds.

In the Caribbean, frigatebirds were called Man-of-War birds by English mariners. This name was used by English explorer, navigator, and naturalist William Dampier (1651-1715) in his book An Account of a New Voyage Around the World (1697). He writes: “The Man-of-War (as it is called by the English) is about the bigness of a Kite, and in shape like it, but black; and the neck is red. It lives on Fish yet never lights on the water, but soars aloft like a Kite, and when it sees its prey, it flys down head foremost to the Waters edge, very swiftly takes its prey out of the Sea with his Bill, and immediately mounts again as swiftly; never touching the Water with his Bill. His Wings are very long; his feet are like other Land-fowl, and he builds on Trees, where he finds any; but where they are wanting on the ground.“

Fregata magnificens Magnificent frigatebird

This species is found in tropical and subtropical waters, between northern Mexico and Peru on the Pacific coast, and from Florida to southern Brazil along the Atlantic coast. There is also a population on the Galápagos Islands. Formerly, the bird bred on the Cape Verde Islands, but it has now probably gone extinct there.

When passing the Cape Verde Islands on his first voyage across the Atlantic in 1492, explorer Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) encountered this bird, using the term rabiforçado (‘forktail’) for it. His journal was cited in the 1530s by Spanish friar Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566): “They saw a bird that is called rabiforçado, which makes the boobies throw up what they eat in order to eat it herself, and she does not sustain herself on anything else. It is a seabird, but does not alight on the sea nor depart from land 20 leagues [about 100 km]. There are many of these on the islands of Cape Verde.”

Circling magnificent frigatebirds, Tortuguero, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Magnificent frigatebirds, resting on poles, Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hirundinidae Swallows and martins

A large family with 19 genera and about 90 species, distributed around the world on all continents, including Antarctica, where the barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) is an occasional visitor. The greatest diversity is found in Africa.

Progne American martins

A genus of 9 species, found from southern Canada southwards through Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean to Argentina, and also on the Galapagos Islands.

These birds nest in various cavities, in river banks and buildings, or in old woodpecker holes.

The generic name is taken from the Greek mythology. Procne was a princess, married to King Tereus of Thrace. However, Tereus lusted after her beautiful younger sister Philomela, locked her away, and raped her. Philomela threatened to tell everybody about his conduct, and to prevent her from doing so he cut off her tongue.

When Procne discovered her sister’s awful fate, she took revenge against her husband by murdering their only child, a young boy named Itys, cooked him, and served him as a meal to her husband.

Finishing his meal, Tereus asked where his son was, and Procne told him the truth, hurling the son’s head in his face. Enraged, he grabbed his sword and ran after the fleeing women to kill them. The gods noticed what was going on and transformed them into birds, Tereus to a hoopoe, and the women to a nightingale and a swallow. Greek sources claim that Procne became the nightingale and Philomela the swallow, whereas Roman authors tend to maintain the opposite.

Progne chalybea Grey-breasted martin

This species, divided into 3 subspecies, breeds from western and eastern Mexico through Central America southwards to South America east of the Andes, as far south as central Argentina and Uruguay. It is also found on Trinidad.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘steel-coloured’, alluding to the steel-blue colour on its back.

Grey-breasted martin, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. Despite the common name, breast and belly are white on some birds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Icteridae

A diverse group of about 105 species, including the New World blackbirds, New World orioles, the bobolink, meadowlarks, grackles, cowbirds, oropendolas, and caciques.

Despite the names blackbird and oriole, these birds are not closely related to the Old World blackbird (Turdus merula) or the Old World orioles (Oriolus). These two groups were named by early settlers due to their resemblance to the Old World birds.

Icterus New World orioles

A large genus with about 33 species, found in the major part of the Americas, except the polar region.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ikteros (‘jaundice-yellow’), originally the name of a yellow bird, perhaps the golden oriole (Oriolus oriolus), the sight of which was said to cure jaundice.

Icterus pustulatus Streak-backed oriole

This beautiful bird is found from north-western Mexico along the Pacific coast to western Costa Rica. It is partial to open arid woodland, but may also be observed in grasslands and shrubberies.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pustula (‘pimple’), perhaps alluding to the dark spots on the back.

Male streak-backed oriole, subspecies sclateri, feeding in flowers of Caesalpinia eriostachys, Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Psarocolius Oropendolas

This genus, comprising 9 species, is found from southern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina, and also on Trinidad & Tobago.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek psar (‘starling’) and koloios (‘jackdaw’). Apparently, German naturalist Johann Georg Wagler (1800-1832), when he introduced the genus in 1827, found that these birds looked like a mixture of a starling and a jackdaw.

Wagler died young, as he accidentally shot himself while on a collecting trip near München in 1832.

Psarocolius montezuma Montezuma oropendola

This striking bird is distributed along the Caribbean coast, from southern Mexico eastwards to Panama, and it is also found on the Pacific coast in Honduras and Nicaragua. It breeds in colonies, easily identified by the long, pendent nests, which are attached to branches.

The specific name refers to Aztec Emperor Montezuma Xocoyotzin (1480-1520), who was killed by his own subjects. They were enraged at his support to the Spanish conquistadors, led by Hernán Cortés (1485-1547).

Singing Montezuma oropendola, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colony of Montezuma oropendola, Tortuguero National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Montezuma oropendola with nesting material, Tortuguero National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quiscalus Grackles

This genus, counting 7 species, is found from southern Canada southwards to northern South America.

The generic name was taken from the specific name of Gracula quiscula, applied in 1758 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) to the common grackle, today called Quiscalus quiscula. It may be a Carib word, Quisqueya (‘the mother of all lands’), alluding to the island of Hispaniola, or it may stem from the Castilian quisquilla, which means ‘a trifling dispute’, referring to the noisy behaviour of these birds.

The common name stems from the old English word gracule, which can be traced back to 1772. It is an Anglizised form of the Latin word graculus, the name of an unidentified bird, which later authors identified as the jackdaw (Coloeus monedula). To me, grackles do not at all resemble the jackdaw!

Quiscalus mexicanus Great-tailed grackle

Divided into 8 subspecies, this common bird has a vast range, found from Peru and Venezuela northwards to the United States, where it has spread considerably during the last hundred years, today found as far north as Oregon and as far east as Minnesota and Louisiana.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Male great-tailed grackle, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female great-tailed grackle, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jacanidae Jacanas

A family of 8 species in 6 genera, distributed in tropical wetlands around the globe. These birds are characterized by having very long toes, an adaptation to walking on floating vegetation.

Jacana New World jacanas

A small genus with 2 species, the northern jacana (below) and the wattled jacana (Jacana jacana), which is found from Panama southwards to north-eastern Argentina and Uruguay.

Jacana was the spelling that Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) used when he named the wattled jacana Parra jacana in 1766. The original Portuguese spelling was jaçana (pronounced approximately zasana), which was derived from a local Tupi name of the bird, ñahana.

Jacana spinosa Northern jacana

This colourful bird occurs in wetlands, from western and eastern Mexico eastwards to western Panama, and also on the larger Caribbean islands Cuba, Hispaniola, and Jamaica.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘prickly’, alluding to a yellow spine on the wing edge, which is used to defend themselves and their chicks.

Northern jacana, stretching a wing, Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern jacana, stretching its wings, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. Note the spine on the wing. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding immature northern jacana, Palo Verde National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Laridae Gulls, terns, and skimmers

This large family, comprising 22 genera with about 100 species, is distributed across the globe.

Many members are described on the page Animals – Birds: Gulls.

Leucophaeus

A small genus of 5 medium-sized gulls, found in the New World, from Canada southwards to southern South America. Until recently, they were placed in the genus Larus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and phaios (‘dusky’), alluding to the dark plumage of most species, and to the white crescent above and below the eyes.

Leucophaeus atricilla Laughing gull

This medium-sized gull is quite common, breeding in the Great Lakes area, and from Maine along the coast southwards to the Mexican border, and also in the Caribbean. In winter, it is found in the south-eastern United States, the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America, and along the coasts of South America, eastwards to northern Brazil, southwards to southern Peru.

The specific name is derived from the Latin atra (‘black’) and cilla (‘tail’). This is puzzling, as the laughing gull has a white tail. According to the Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), when naming the bird, may have intended to write atricapilla (‘black-haired’), alluding to its black head in the breeding plumage.

The common name refers to its call.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Coast at Capo Matapalo, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica, with resting immature laughing gulls and Cabot’s terns (see below). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thalasseus Crested terns

A genus of 8 species, distributed in most of the world. The genus had originally been created in 1822 by German zoologist and lawyer Friedrich Boie (1789-1870), but was later abolished, until a genetic study in 2005 concluded that the crested terns should be placed in a separate genus.

Friedrich Boie described many new species and several new genera of birds. He and his brother Heinrich also described about 50 new species of reptiles.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘fisherman’, ultimately from thalassa (‘sea’).

Thalasseus acuflavidus Cabot’s tern

This bird was previously regarded as a subspecies of the sandwich tern (T. sandvicensis). They are extremely similar, and why this split was made is a mystery to me.

Cabot’s tern is divided into 2 subspecies, breeding on the Atlantic Coast from Delaware southwards, around the Gulf of Mexico to Belize, on the Bahamas and many Caribbean islands, and from northern South America southwards along the Atlantic coast to northern Argentina. Northern populations are migratory. It is a common winter visitor to the Pacific coast, from south-eastern Mexico southwards to Peru.

The specific name is derived from the Latin acus (‘needle’) and flavidus (‘yellowish’), alluding to the yellow point on the long, sharp bill. The common name refers to American physician and ornithologist Samuel Cabot III (1815-1885), who described the species in 1847, based on a skin collected in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Resting Cabot’s terns and immature laughing gulls (see above), Capo Matapalo, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thalasseus maximus Royal tern

This large tern is widespread in the Americas, breeding along the Atlantic coast from Virginia southwards to Florida and along the Gulf of Mexico to southern Texas, in Yucatan and off northern Honduras, in the entire Caribbean, from northern Venezuela eastwards to Cayenne, and also in southern Brazil, Uruguay, and north-eastern Argentina. On the Pacific coast, it breeds from southern California southwards around Baja California to Sinaloa.

The northernmost populations are migratory. It is a common winter visitor along the coasts of Mexico and Central America, and also along the entire Brazilian coast.

Royal terns, resting on poles, Cahuita, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pandionidae

Pandion haliaetus Osprey

This striking raptor, the only member of the family, is found on almost the entire planet, avoiding the polar regions and most desert areas.

The generic name refers to Pandion, a mythical king of Athens. However, there were two kings with that name in Athens. They were frequently confused by later authors, but neither was ever metamorphosed into a bird of prey. Pandion II had four children, one of whom, Nisus of Megara, was transformed into a hawk. This metamorphosis, which is related in detail under Micronisus gabar (on the page Birds in Africa), was probably what French naturalist Marie Jules César Lelorgne de Savigny (1777-1851) had in mind, when he moved the osprey to a separate genus in 1809.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek hals (‘sea’) and aetos (‘eagle’).

The name osprey was first recorded around 1460, a corruption of the Latin avis praedae (‘bird of prey’).

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Osprey, resting in a red mangrove tree (Rhizophora mangle), Monterrico, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Passerellidae New World sparrows

When the European settlers arrived in America, a large group of small birds reminded them of the sparrows back home, so they named them ‘sparrows’. However, these birds are not closely related to Old World sparrows, family Passeridae.

For many years, they were placed with the Old World buntings in the family Emberizidae, but genetic research has shown that they form a monophyletic group of uncertain relationship with the buntings, and the family Passerellidae has been erected, originally established in 1851 as a subfamily, Passerellinae, by German ornithologist Jean Louis Cabanis (1816-1906).

New World sparrows are seed-eating birds with conical bills, comprising about 138 species in 30 genera, including some genera, which were formerly placed in the tanager family (Thraupidae, below).

Zonotrichia

A small genus with 5 species, 4 of which are North American. The fifth is the rufous-collared sparrow (below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek zone (‘band’) and thrix (‘hair’), alluding to the boldly streaked crown of most of the species.

Zonotrichia capensis Rufous-collared sparrow

This species lives in a wide range of open habitats, at scattered locations from south-eastern Mexico through Central America, and thence southwards through most of South America to Tierra del Fuego. An isolated population is found on the Caribbean island Hispaniola. In Costa Rica, a local name of this bird is comemaíz (‘maize-eater’).

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Chile.

Rufous-collared sparrow, El Castillo, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pelecanidae Pelicans

These huge water birds have an enormous bill and a very large gular pouch, which swells tremendously, when the bird is fishing – like some kind of basket. The tongue, however, is quite small, allowing the bird to swallow large fish.

Formerly, it was presumed that the gular sac was a means to store food for several days, but this is not the case. This belief was the cause of a funny limerick, written in 1910 by American poet Dixon Lanier Merritt (1879-1972):

Oh, a wondrous bird is the pelican!

His beak holds more than his belican.

He takes in his beak

Food enough for a week.

But I’ll be darned if I know how the helican.

There are 8 species in a single genus, Pelecanus. Formerly, they were divided into two groups, one with 4 species, having a mainly white adult plumage, the great white (P. onocrotalus), the Dalmatian (P. crispus), the American white (P. erythrorhynchos), and the Australian (P. conspicillatus), and another, containing the remaining 4 species, having a mainly grey or brown adult plumage, the pink-backed (P. rufescens), the spot-billed (P. philippensis), the brown (below), and the Peruvian (P. thagus).

However, recent DNA research has revealed that the 5 Old World species (great white, Dalmatian, pink-backed, spot-billed, and Australian) form one lineage, whereas the American white, the brown, and the Peruvian form another. The great white was the first to diverge from the common ancestor, which suggests that pelicans evolved in the Old World and later spread into the Americas.

Traditionally, pelicans were thought to be related to cormorants, darters, gannets, frigatebirds, and tropicbirds, but genetic research has shown that they form an order, Pelecaniformes, together with herons, the hamerkop (Scopus umbretta), and the shoebill (Balaeniceps rex).

Pelecanus occidentalis Brown pelican

A widespread bird in the Americas, distributed along both coastlines, from Nova Scotia, Canada, south to the mouth of the Amazon River, and from British Columbia, Canada, south to northern Chile and the Galapagos Islands.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘western’, derived from occidens (‘west’).

Brown pelicans, resting on coastal rocks, Capo Matapalo (top), and Corcovado National Park, both Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brown pelican, resting in a tree, Capo Matapalo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Soaring brown pelicans, Capo Matapalo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phasianidae Pheasants and allies

This family, containing about 190 species, includes pheasants, partridges, junglefowl, Old World quails, peafowl, grouse, and many others. These birds are found worldwide, except in Antarctica.

Meleagris Turkeys

A small genus with two species, the wild turkey (M. gallopavo), which is presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada, and the ocellated turkey (below).

The generic name is the classical Greek word for the helmeted guineafowl (Numida meleagris). In his book The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names (2010), James Jobling writes: “The names Turkeycock and Turkeyhen were used for guineafowl in the 16th and early 17th Centuries, because they were brought from Africa to Europe through the Ottoman or Turkish dominions, and by this confusion Linnaeus used the generic term Meleagris for the American turkey (M. gallopavo), which was unknown to the ancients. When the guineafowl and turkey were subsequently distinguished as separate species, turkey was erroneously retained for the American bird.”

Meleagris ocellata Ocellated turkey

This marvellous bird is restricted to the Yucatan Peninsula. Previously, it was probably found in a larger area, but extensive hunting, combined with habitat destruction, has led to its decline, and today it is regarded as endangered.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘marked with small eyes’, derived from ocellus (‘small eye’), diminutive of oculus (‘eye’). The name refers to the pattern at the end of the tail feathers, which have been likened to the ‘eyes’ on the tail feathers of the peacock (Pavo cristatus).

The ocellated turkey is rather common and confiding in Tikal National Park, Guatemala. These males were photographed early in the morning. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Preening male, Tikal National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Picidae Woodpeckers

Members of this family, comprising about 240 species in 35 genera, are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and polar regions. Most species are known for their characteristic way of foraging, pecking on tree trunks and branches. Many species communicate by drumming with their beak on a tree trunk.

Campephilus

Today, this genus, comprising 11 species, is found from northern Mexico southwards to the southern tip of South America. It includes two iconic species, which are today probably extinct, the ivory-billed woodpecker (C. principalis), which was found in southern United States and on Cuba, and the imperial woodpecker (C. imperialis) of Mexico.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kampe (‘caterpillar’) and philos (‘loving’).

Campephilus guatemalensis Pale-billed woodpecker

This large woodpecker is distributed from eastern and western Mexico southwards to western Panama. It lives in various types of forest, including mangrove.

Pale-billed woodpecker, Arenal Observatory, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Psittacidae African and American parrots

Formerly, the family Psittacidae contained about 360 species in 92 genera, distributed in most warmer parts of the world. However, recent genetic research has had the effect, that Asian, Australian, and Indian Ocean island parrots, and the African lovebirds (Agapornis), have been moved to a separate family, Psittaculidae, with altogether 55 genera and about 195 species.

Today, the family Psittacidae has two subfamilies, African parrots (Psittacinae) with 2 genera and about 12 species, and American parrots (Arinae), with 32 genera and about 150 species.

Amazona Amazon parrots

A large genus with 33 species, distributed from northern Mexico and the Caribbean southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The generic name was adapted from the French name amazone, given to various parrots from the Amazonian rainforests by French naturalist and mathematician Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788).

Amazona auropalliata Yellow-naped amazon

This bird inhabits the Pacific coast, from southern Mexico eastwards to western Costa Rica, and the Caribbean coast, from southern Mexico eastwards to north-eastern Nicaragua. It is critically endangered, as it has declined by more than 90% in later years.

The specific name is derived from the Latin aurum (‘gold’) and pallium (‘mantle’), alluding to the yellow nape.

Yellow-naped amazon, Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Amazona autumnalis Red-lored amazon

This colourful species lives in humid evergreen or semi-deciduous forests, in some places up to elevations around 1,100 m. It is distributed from eastern Mexico along the Caribbean coast eastwards to Columbia and western Venuzuela. On the Pacific coast, it occurs from Costa Rica eastwards to Ecuador.

It has established feral populations in several Californian cities, and a pair breeding in the outskirts of San Salvador in 1995 and 1996 was possibly also feral birds.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the autumn’. What it refers to is not clear.

Red-lored amazon, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ara Large macaws

A genus of 9 species of wonderful large parrots, of which one, the Cuban macaw (Ara tricolor) was hunted to extinction in 1864. The 8 living species range from western Mexico southwards to northern Argentina.

The generic name is onomatopoetic, the word for macaws in the Brazilian Tupi language. The common name is used for several genera of larger parrots. It stems from Portuguese macau, which was taken from a word in a Brazilian language, perhaps the Tupi word macavuana, which may be the name of a palm species, whose fruits formed part of the diet of macaws.

Ara macao Scarlet macaw

This marvellous bird is native to humid evergreen lowland forests and savannas, from south-eastern Mexico through Central America southwards to Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. It is also found on Trinidad, and on the Pacific island of Coiba. It has declined in some areas due to habitat destruction, and many are captured for the pet trade. In some areas, mainly nature reserves, it remains fairly common.

It is the national bird of Honduras.

The specific name is explained above, under genus.

Scarlet macaw, eating fruits from a tree, Capo Matapalo, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eupsittula American parakeets, conures

A small genus of 5 species, found from northern Mexico southwards to northern Argentina, with one species also on Jamaica. They were previously placed in the genus Aratinga.

The generic name combines the Ancient Greek eu (‘good’) with the Latin psittula (‘small parrot’). The alternative common name is derived from the Latin conurus, originally from Ancient Greek konos (‘cone’) and oura (‘tail’), thus ‘with a cone-shaped tail’.

Eupsittula canicularis Orange-fronted parakeet, half-moon conure

This small parakeet is found along the Pacific coast, from Sinaloa, Mexico, southwards to south-western Costa Rica. It lives in a variety of open landscapes, including forest edges, deciduous woodlands, swamp forest, savanna, and shrubberies.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of Canicula’ (the Dog Star or Sirius), a very bright star in the constellation of Canis Major (‘Larger Dog’). What it refers to is not clear.

Orange-fronted parakeet, feeding on flowers of Gliricidia sepium, Bagaces, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rallidae Rails and allies

An almost worldwide family, divided into 41 genera with altogether c. 156 species, including gallinules, waterhens, coots, crakes, and rails.

Aramides Woodrails

A genus of 8 species, found from central Mexico southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The generic name combines another generic name, Aramus (the limpkin, which is presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada), and Ancient Greek oides (‘resembling’).

Aramides albiventris Russet-naped woodrail

This bird, divided into 5 subspecies, lives in a variety of habitats, including humid forests, swamps, and mangroves. It occurs from the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Oaxaca eastwards to north-eastern Costa Rica. It was previously regarded as a subspecies of the grey-necked woodrail (A. cajaneus).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white-bellied’, derived from albus (‘white’) and ventris (‘belly’).

Russet-naped woodrail, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ramphastidae

This family contains 5 genera of colourful birds, comprising about 43 species, distributed from south-eastern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

Pteroglossus Araçaris

A genus of 14 species, found from south-eastern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pteron (‘feather’) and glossa (‘tongue’), alluding to the very long tongue of these birds, which looks like a feather.

The common name is the Portuguese spelling of the Tupi word arassari (‘little bright bird’), a name given to the black-necked araçari (P. aracari).

Pteroglossus torquatus Collared araçari

This species lives in various forest types, including secondary growth and plantations, from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to Columbia, western Venezuela, and coastal Ecuador.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘collared’, derived from torques (‘collar’), presumably alluding to the black ‘collar’.

Collared araçari, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Collared araçari, eating palm fruits, Tikal National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ramphastos Typical toucans

A genus of 8 brightly coloured birds, living in various types of forest and grasslands. They are distributed from south-eastern Mexico southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The generic name takes some explanation. Originally, in his Historiæ animalium, Liber III, published in 1555, Swiss physician and naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) called toucans Ramphestes, which means ‘snouted’ in Ancient Greek, derived from rhamphos (‘bill’). However, this name was misspelt by Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) in his work Ornithologia (1599-1603). Aldrovandi’s name was subsequently adopted by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who claimed that the word meant ‘a broad sword’, alluding to the form of the bill of these birds.

The common name is derived from the Tupi word tukan, which is an imitation of the call of one of the species.

Ramphastos sulfuratus Keel-billed toucan

This marvellous bird lives in rainforests, from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to Columbia and western Venezuela. It is the national bird of Belize.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sulpher-coloured’, referring to the colour on the neck and upper breast.

Keel-billed toucan, eating palm fruits, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scolopacidae Sandpipers and allies

This large family, comprising about 15 genera and c. 95 species, is found across the globe, except in Antarctica.

Actitis

This genus contains only two species, the common sandpiper (A. hypoleucos), presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and the spotted sandpiper (below).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aktites (‘living on the coast’), from akte (‘coast’).

Actitis macularia Spotted sandpiper

This bird breeds in a vast area of North America, from subarctic areas of Alaska and Canada southwards almost to the Mexican border. The majority are migratory, spending the winter from southern United States southwards through Central America and the Caribbean to central Chile and northern Argentina, both inland and along the coast.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘spotted’, referring to the dark spots on the underside in the breeding plumage.

Spotted sandpiper, resting on a drift log (top), and on a rock, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thraupidae Tanagers

As of today, tanagers are a family with 106 genera and about 383 species, restricted to the Western Hemisphere, and mainly to the tropics, about 60% living in South America. Many species are endemic to a relatively small area.

Recent genetic studies have greatly re-arranged this family. A number of species formerly placed in the family have been moved to other families, but the opposite has also taken place.

Cyanerpes Typical honeycreepers

A small genus of 4 small birds, found from southern Mexico southwards to Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil, and also on Trinidad & Tobago, and on Cuba (where maybe introduced). The males are bright blue, whereas females are brownish or greenish.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kyanos (‘dark-blue’) and herpes (‘creeper’).

Cyanerpes cyaneus Red-legged honeycreeper

This gorgeous bird is distributed from southern Mexico southwards to Peru, Bolivia, and central and eastern Brazil. It is also found on Trinidad & Tobago, and on Cuba (where it may be introduced). It has strayed a few times to southern Texas.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kyanos (‘dark-blue’) – certainly very blue indeed!

Male red-legged honeycreeper, feeding in flowers of blue porterweed (Stachytarpheta frantzii), Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ramphocelus

This genus of brilliantly coloured birds, comprising 9 species, is found from central Mexico southwards to Paraguay and northern Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek rhamphos (‘bill’) and koilos (‘concave’), referring to the concave bill of some species.

Ramphocelus passerinii Scarlet-rumped tanager

This common species occurs from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to western Panama, living in a variety of habitats, including forest edges, secondary forest, gardens, and fields with scattered bushes, from sea level up to an elevation of about 1,200 m.

The specific name honours Italian naturalist Carlo Passerini (1793-1857), curator of the Royal Natural History Museum in Florence.

Previously, birds in Costa Rica and Panama were regarded as a separate species, Cherrie’s tanager (R. costaricensis).

Male scarlet-rumped tanager, displaying its scarlet rump, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sporophila Seedeaters

A large genus with about 40 species of small, seed-eating birds, which resemble finches. They are distributed from northern Mexico southwards to southern South America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sporos (‘seed’) and philos (‘to love’).

Sporophila corvina Variable seedeater

This bird breeds from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to coastal Columbia, Ecuador, and extreme northern Peru. It was formerly considered a subspecies of the wing-barred seedeater (S. americana). Its plumage is mainly black, but, as its name implies, it is extremely variable.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘raven-like’, alluding to the mainly raven-black plumage of the male.

Variable seedeater, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Thraupis Typical tanagers

This genus contains 7 species, found from central Mexico southwards to Paraguay and southern Brazil.

The generic name refers to an unidentified small bird, perhaps some kind of finch, mentioned by Greek scientist and philosopher Aristotle (384-322 B.C.).

Thraupis episcopus Blue-grey tanager

This species is common in open woodland, gardens, and cultivated areas, from central Mexico southwards to northern Bolivia and central Brazil. It is also found on the Caribbean islands Trinidad & Tobago, and has been introduced to Peru, around the capital Lima.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘bishop’, referring to the blue plumage. Bishops wear a blue or purple dress.

This blue-grey tanager is feeding on a fallen fruit of great morinda (Morinda citrifolia), Tortuguero National Park, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Threskiornithidae Ibises and spoonbills

A worldwide family with 14 genera of long-legged water birds, found on every continent, except Antarctica. Traditionally, this family has been classified into two subfamilies, the ibises and the spoonbills. However, a recent genetic study concludes that spoonbills are closely related to the Old World ibises, whereas the New World ibises are an early offshoot. (Source: J.L. Ramirez, C.Y. Miyaki & S.N. del Lama 2013. Molecular phylogeny of Threskiornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Genetics and Molecular Research 12 (3): 2740-2750)

Eudocimus

A small genus of two American species, the white ibis (below) and the scarlet ibis (E. ruber), which breeds in northern and north-eastern South America and south-eastern Brazil.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eudokimos (‘glorious’), originally from eu (‘good’) and dokimos (‘excellent’).

Eudocimus albus American white ibis

This striking species is living in wetlands, from Virginia along the coast southwards to Texas, along both coasts of Mexico, in the Caribbean and Central America, and in north-western South America.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white’.

Other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

White ibises, a snowy egret (Egretta thula), and a black-necked stilt (Himantopus mexicanus), which takes off, Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. The brown bird is an immature. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tityridae Tityras and allies

The 45 members of this family were formerly placed in the families Tyrannidae (below), Pipridae, and Cotingidae.

Tityra Tityras

Traditionally, these birds were placed in the tyrant flycatcher family Tyrannidae (below), but genetic research has had the effect that they have been moved to a separate family. The genus has 3 rather similar members, found from western and eastern Mexico southwards to eastern Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina.

The generic name stems from the Greek mythology. The name tityri was applied to the satyrs and other raucous companions of Pan and Bacchus, referring to the noisy, aggressive behaviour of tityras.

Tityra semifasciata Masked tityra

This striking bird occurs from western and eastern Mexico southwards to northern Bolivia, central Brazil, and eastern Paraguay, living in various types of forest and woodland.

The specific name is derived from the Latin semi (‘half’) and fascia (‘band’), probably alluding to the facial mask being only half a collar.

Masked tityra, eating berries, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troglodytidae Wrens

This family of mostly small and brown birds consists of 19 genera with about 88 species, all but one living in the New World.

Campylorhynchus

A genus of at least 15 species of rather large wrens, including the largest, the giant wren (C. chiapensis) of southern Mexico and adjacent Guatemala, which grows to 22 cm long. The genus is distributed in southern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kampylos (‘curved’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’).

Campylorhynchus capistratus Rufous-backed wren

This striking wren breeds from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to western Costa Rica. It inhabits rather dry ares, including open woodland, secondary forest, shrubberies, and grasslands.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘haltered’. It may refer to the conspicuous black line from the bill through the eye.

Previously, this bird was regarded as a subspecies of the rufous-naped wren (C. rufinucha), but that species has been split into 3 species.

Rufous-backed wren, Bagaces, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rufous-backed wren under a roof, made of palm leaves, La Avellana, Monterrico, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troglodytes Typical wrens

A genus of about 12 species of tiny birds, one of which, the Eurasian wren (T. troglodytes), is widespread in the Old World, whereas the rest live in the New World.

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘one who dwells in holes’, referring to the nest of these birds, which is almost circular, with a small entrance hole.

Troglodytes musculus Southern house wren

This tiny bird is distributed from southern Mexico southwards to southern South America. It was formerly regarded as a subspecies of the widespread house wren, today called northern house wren (T. aedon).

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin mus (‘mouse’), thus ‘litte mouse’, referring to its tiny size.

Southern house wren, Puerto Jiménez, Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trogonidae Trogons and quetzals

This is the only family in the order Trogoniformes, comprising 7 genera with 46 species. They are found in tropical forests worldwide, with the greatest diversity in the New World.

Pharomachrus Quetzals

A genus of 5 gorgeous birds, distributed in tropical forests, from south-eastern Mexico southwards to Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pharos (‘mantle’) and makros (‘long’), alluding to the wing and tail coverts of the resplendent quetzal (below). The second h is probably a writing mistake.

The common name is derived from the Nahuatl word quetzalli (‘large brilliant tail feather’), originally from quetz (‘to stand up’), alluding to an erect plume of feathers. Previously, the word quetzal was only used for the resplendent quetzal.

Pharomachrus mocinno Resplendent quetzal

The tail feathers of the male of this fantastic bird may be up to 1 m long. It is distributed from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to western Panama, mainly living in montane cloud forests. It is the national bird of Guatemala, whose image is found on the country’s flag and coat of arms, and which also lends its name to the Guatemalan currency.

The specific name was given in honour of Mexican naturalist José Mariano Mociño Suárez Lozano (1757-1820), who conducted research on botany, geology, and anthropology.

The story behind the rather poor picture below is this: I went to the protected area Biotopo del Quetzal, near Salamá, Baja Verapaz, Guatemala, where I stayed at a small lodge at the road side. During the following days, I roamed the cloud forest, hoping to observe the resplendent quetzal. The vegetation in this forest was indeed lush, the huge trees festooned with epiphytes, including mosses, lichens, ferns, and various seed plants, mostly bromeliads, of the pineapple family (Bromeliaceae), and orchids.

I observed very few birds in the forest, and no quetzal. On my last day in the area, I returned to the lodge, rather disappointed that I didn’t succeed in observing this enigmatic bird. I took my seat at one of the outdoor tables to enjoy a cup of coffee, when the lodge owner, who was fiddling with something in his car engine, pointed to a group of trees, uttering only one word: “Quetzal!”

There, high up in a tree, sat a gorgeous male resplendent quetzal, and, what was more important, it was not moving. Here was my chance to get photographs! I sneaked closer to the tree, but from this angle a photograph of the bird was not possible. I would have to do with pictures from the road, far away or not.

Now, however, another problem occurred. The wife of the lodge owner was cooking lunch, and smoke from the cooking drifted past the tree, where the bird was sitting, making my pictures hazy. I had to wait for breaks in the puffs of smoke to take my pictures, but luckily the quetzal was still not moving. Trogons are rather lethargic birds.

Finally, I managed to get a few photographs, but definitely nothing to bragg about!

Male resplendent quetzal, Biotopo del Quetzal, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trogon Typical trogons

A genus with 20 species, distributed from southern Arizona and New Mexico southwards to northern Argentina. In the Caribbean, 3 species occur on Trinidad & Tobago.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek trogo (‘to chew’ or ‘to gnaw’). Trogons nest in cavities, which they themselves gnaw into rotting wood or termite nests, one species even nesting in wasps’ nests.

Trogon massena Slaty-tailed trogon

This bird occurs from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to coastal Columbia and northern Ecuador. It feeds on fruits and insects, and often follows capuchin monkeys (Cebus) to catch insects disturbed by them.

The specific name honours French ornithologist François Victor Masséna, 2nd Duke of Rivoli and 3rd Prince of Essling (1799-1863), who had accumulated a bird collection of 12,500 specimens, which later ended up in the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

Male slaty-tailed trogon, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tyrannidae Tyrant flycatchers

A very large family, comprising 104 genera with more than 400 species, occurring throughout the Americas. Tyrant flycatchers vary greatly in shape, patterns, size, and colours. Some members superficially resemble Old World flycatchers, which they are named after.

The tyrant part of the name of these birds goes back to English naturalist Mark Catesby (1683-1749) who studied flora and fauna in the New World. He labeled the eastern kingbird (Tyrannus tyrannus) a tyrant due to its aggressive behaviour, and this name was adopted by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), when he classified this group of birds. He greatly acknowledged Catesby’s work, so he named the family Tyrannidae.

Megarynchus pitangua Boat-billed flycatcher

As its name implies, this bird, the only member of the genus, has a large, boat-shaped bill. It breeds in open woodland, from southern Mexico southwards to the entire Brazil, eastern Paraguay, and north-eastern Argentina, and also on Trinidad.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek megas (‘large’) and rhynkhos (‘bill’), whereas the specific name is derived from the Tupi name pitanguá guacú for a large flycatcher, perhaps this species.

Boat-billed flycatcher, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Myiozetetes

A small genus of 4 mainly yellow species, distributed from north-western Mexico southwards to eastern Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek myias (‘fly’) and zetetes (‘one that searches’).

Myiozetetes similis Social flycatcher

This bird, divided into 8 subspecies, is very widespread, found from north-western Mexico southwards to eastern Paraguay and north-eastern Argentina. It has an orange or vermilion crown stripe, which, however, is usually concealed.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘the similar one’, indicating its similarity to several other members of the tyrant flycatcher family.

Social flycatcher, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Social flycatcher, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tyrannus Kingbirds

A genus of about 13 species, distributed from southern Canada southwards to Argentina. Northern species are migratory.

The generic name is explained above under family name. Like the common name it refers to the aggressive behaviour shown by kingbirds towards each other and also towards other species. When defending their nest they will often attack predators larger than themselves, including hawks, crows, and squirrels.

Tyrannus forficatus Scissor-tailed flycatcher