Autumn

Wonderful autumn foliage display near Williamstown, Massachusetts, United States. Yellow and orange sugar maples (Acer saccharum) are seen in front, whereas the crimson forest in the background is dominated by red maple (Acer rubrum). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This border terrier is standing in a carpet of fallen leaves from a large cherry tree (Prunus avium), Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colour spectrum and size disparity in fruits of cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera), all from the same area, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bright red winter foliage of Chinese tallow-tree (Triadica sebifera), Central Taiwan Science Park, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen apples are a popular food item among butterflies, wasps, and flies. This red admiral (Vanessa atalanta) is sucking juice from a decaying apple, Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Autumn is a second spring, when every leaf is a flower.”

Albert Camus (1913-1960), French writer and philosopher

I have been treading on leaves all day until I am autumn-tired.

God knows all the color and forms of leaves I have trodden on and mired.

Perhaps I have put forth too much strength and been too fierce from fear.

I have safely trodden under foot the leaves of another year.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), American poet, in his poem Leaf Treader, 1935

I love the fitfull gusts that shakes

The casement all the day,

And from the mossy elm tree takes

The faded leaf away,

Twirling it by the window-pane

With thousand others down the lane.

(…)

The feather from the raven’s breast

Falls on the stubble lea.

The acorns near the old crow’s nest

Fall pattering down the tree.

The grunting pigs that wait for all

Scramble and hurry where they fall.

John Clare (1793-1864), English poet, in his poem Autumn

In many parts of the world, autumn is a wonderful time, when the foliage of trees and many other plants change colours, adding a vivid, albeit short, touch to the landscape. Berries and other fruits ripen, fungi abound during wetter periods, and birds start their migration southwards to their wintering quarters.

In this picture, autumn foliage brightens the tundra on the Blosseville Coast, eastern Greenland. Arctic willow (Salix arctica) has yellow leaves, bog bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) reddish leaves, and alpine bearberry (Arctostaphylos alpina) crimson leaves. Lichens and mosses are also present. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gorgeous autumn foliage of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), covering a mountain slope near Conway Summit, Sierra Nevada, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A slope along the Rishi Ganga gorge, Nanda Devi National Park, Uttarakhand, northern India, with scattered Himalayan silver firs (Abies spectabilis) (the dark trees), Himalayan birches (Betula utilis) (yellow foliage), and thickets of barberry (Berberis) (crimson foliage). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Late afternoon sun casts long shadows on a forest floor, covered in fallen leaves of beech (Fagus sylvatica), eastern Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

East American autumn foliage

In autumn, hardwood forests of north-eastern North America are a spectacle to behold, with an outstanding foliage display, when leaves turn crimson, wine-red, orange, or yellow. This display is mainly seen from Quebec southwards to Virginia.

Altingiaceae

Liquidambar Sweetgum

A genus with about 15 species, found in eastern North America, Mexico, Central America, Turkey, East and Southeast Asia, and western Indonesia. The fruits of these plants are ball-shaped, hard, and spiky. Pictures, depicting these fruits, are shown on the pages Plants: Burs, and Silhouettes.

The generic name is derived from the Latin liquidus (‘liquid’) and the Arabic anbar, which, via the Moors, became ambar in Spanish. Amber from members of this genus was formerly used in the cosmetic industry.

Formerly, these trees were placed in the witch-hazel family (Hamamelidaceae), but have since been transferred to Altingiaceae.

Liquidambar styraciflua American sweetgum

This tree is known by a number of other popular names, including hazel pine, bilsted, redgum, satin-walnut, and alligator-wood. It is native to south-eastern United States, and is also found in montane areas of southern Mexico and Central America.

The leaves are almost star-shaped, with 5 to 7 pointed lobes.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek styrax, the name of the tree Styrax officinalis and its fragrant balsam, and from the Latin fluere (‘to flow’), thus ‘flowing with fragrant gum’.

A close relative, Chinese sweetgum (L. formosana), is presented below in the section Asiatic autumn foliage.

Gorgeous red autumn leaves of American sweetgum, Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge, Georgia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anacardiaceae Sumac family

Rhus Sumac

Sumacs are a genus of shrubs and trees with about 35 species, distributed in subtropical and temperate areas, especially around the Mediterranean, and in Asia, Australia, and North America.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek rhous, the name of sumac. This word is derived from Ancient Syriac summaq (‘red’), referring to the red fruits of the genus. They have an acrid taste and are used as a spice in the Middle East.

Many other species, which were formerly placed in Rhus, have since been transferred to the genus Searsia, others to Toxicodendron, including poison ivy (below), and poison oak, presented in the section West American autumn foliage.

Rhus glabra Smooth sumac

This shrub, also known as white sumac, upland sumac, or scarlet sumac, is very common in the eastern half of the United States, with a patchy occurrence in southern Canada, the western U.S., and in Tamaulipas, north-eastern Mexico.

It produces an abundance of berries, which are eagerly sought out by birds. The seeds, which pass unharmed through their gut, are spread with the bird droppings and are thus able to colonize open areas and forest edges.

Brilliant autumn foliage of smooth sumac, Williamsburg, Massachusetts. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhus typhina Staghorn sumac

This species is found in eastern North America, primarily in south-eastern Canada and from the Great Lakes eastwards to the Appalachian Mountains, with a spotty occurrence westwards to Minnesota, southwards to Mississippi. It is widely cultivated as an ornamental elsewhere in temperate areas.

In North America, the fruits are soaked in cold water to make ‘pink lemonade’, a refreshing beverage, rich in vitamin C.

When describing this plant in 1756, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) used the phrase Ramis hirtis uti typhi cervini, meaning “the branches are rough like antlers in velvet.”

Various autumn colours on a staghorn sumac, naturalized in Nature Reserve Vorsø, Horsens Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Toxicodendron

Members of this genus, which contains about 28 species, were previously placed in the genus Rhus (above). They are found in the Americas, from Canada southwards to Bolivia, and in eastern Asia, from Sakhalin Island and Japan southwards to Indonesia, westwards to Pakistan.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek toxikos (‘poison’) and dendron (‘tree’).

Toxicodendron radicans Poison ivy

The only thing that poison ivy has in common with the true ivy (Hedera helix) is its climbing habit. This plant, which was formerly called Rhus radicans, is very common in the eastern half of North America, from Labrador southwards to Texas and Florida.

As with other members of this genus, it contains the toxic urushiol, which causes rashes and other allergic reactions in some people. In his delightful book All about Weeds, American botanist Edwin Spencer (1881-1964) writes about it: “With alliterations, we may almost truthfully say ‘the worst weed of the woods’ or ‘the worst weed of waste places’ is the poison ivy. If its toxin affected the skin of every one as it does that of a few, it would not be necessary to qualify these allitterations. They would be literally true. This is the one weed, however, that every one who lives in the country, and all who visit it, should know. Those who are immune to its poison have nothing to fear, but no one knows whether he is immune or not until he has come in contact with some part of the plant. If he is susceptible he will long remember that day, and if he is wise he will develop his observational powers, until they equal those of a first-class botanist, when he approaches a likely habitat of this snake of the woods.”

In his excellent book The Green Pharmacy, American botanist and herbalist James A. Duke (1929-2017) recommends the juice of soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) as the best remedy, if you have been into contact with poison ivy or other Toxicodendron species. Smear the juice over the affected area to neutralize the poison.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘taking root’, from radix (‘root’), alluding to the spreading roots of this plant.

A close relative, the western poison oak (T. diversilobum), is presented below in the section West American autumn foliage.

Autumn foliage of poison ivy, Muttontown Preserve, Long Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celastraceae Staff-tree family

Euonymus Spindle tree, burning-bush

A large genus with about 130 species of deciduous or evergreen shrubs, small trees, or climbers. Most species are native to eastern Asia, with 50 species endemic to China. Others occur in Europe, northern Africa, Madagascar, Indonesia, New Guinea, eastern Australia, North America, Mexico, and Central America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eus (‘good’) and onoma (‘name’). It is not clear why Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) applied this name to this genus.

Euonymus atropurpureus Eastern burning-bush

This bush is native to eastern North America, primarily found in a huge area south of the Great Lakes, but with small, scattered populations elsewhere, from Minnesota and Ontario southwards to Texas and Georgia. It is also widely cultivated.

Formerly, the powdered bark was used by native tribes and pioneers as a purgative.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ater (‘dark’) and purpureus (‘purple’), alluding to the autumn colour of this species.

A close relative, the European spindle tree (E. europaeus), is presented below in the section Fruits: Capsules.

Flaming autumn foliage of an eastern burning-bush, cultivated in Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fagaceae Beech family

Quercus Oak

A genus with about 300-500 species, depending on authority. They are native to the Northern Hemisphere, distributed in the Americas, Asia, Europe, and North Africa.

Male flowers are in pendent catkins, females in mostly erect spikes. The fruit is a nut, called an acorn, partly enclosed in a cup-like structure, the cupule, consisting of overlapping bracts with free tips. (See examples of acorns below in the section Hard-shelled fruits: Acorns.)

The generic name is the classical Latin term for oaks, which probably stems from the name of the Lithuanian god of thunder, Perkunas. In almost all of Europe, the oak was a sacred tree, dedicated to the highest gods, in Greece to Zeus, in Nordic countries to Thor, the god of thunder.

The word oak is from the Anglo-Saxon ek, in ancient Germanic aik, of uncertain origin and meaning.

A number of oaks are presented on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

A few species of eastern American oaks display brilliant autumn foliage.

Quercus alba White oak

This large tree is very common in the north-eastern states, found from Ontario and Quebec southwards through the eastern United States to northern Florida, westwards to Minnesota, and thence southwards to Texas.

Despite its name, the bark of this species is mostly grey, only occasionally white. It can grow very old, some specimens having reached the ripe age of 450 years.

Colourful autumn foliage of white oak, Delaware Water Gap, New Jersey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus coccinea Scarlet oak

As its name implies, this species has brilliant autumn foliage. It mainly grows on dry, acidic soils in the eastern and central United States, from Maine southwards to Georgia, and thence westwards to Missouri and Louisiana.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kokkinos (‘scarlet’).

Scarlet oak really lives up to its name, as seen from these leaves, encountered in Caleb Smith State Park, Long Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Withered leaves of scarlet oak, still hanging on the tree in spring, Bass River State Park, Pine Barrens, New Jersey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lauraceae Laurel family

Sassafras

The native range of this genus, comprising 3 species, is eastern North America, southern China, Taiwan, and northern Vietnam.

The generic name is of Spanish origin, possibly adapted from an unknown indigenous language.

Sassafras albidum Common sassafras

This smallish tree, which grows to about 18 m tall, is widely distributed in the eastern United States, from Maine southwards to northern Florida, westwards to the Great Lakes and eastern Texas. Its autumn foliage displays many colours: yellow, red, pink, orange, and purple.

Ground leaves of sassafras is an ingredient in home-made root beer, and they also act as a thickener and flavouring in gumbo, a spicy herb, which was used by indigenous tribes in the southern United States, and was later adopted into Louisiana Creole cuisine. (Source: C. Nobles 2009. Gumbo, in: S. Tucker & S. Starr, New Orleans Cuisine: Fourteen Signature Dishes and Their Histories, University Press of Mississippi)

Evening light on autumn foliage of common sassafras, Delaware Water Gap, New Jersey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sapindaceae Soapberry family

Acer Maple

In former days, maples, comprising about 130 species of deciduous trees or large shrubs, constituted a separate family, Aceraceae, which is now regarded as belonging to Hippocastanoideae, a subfamily of the soapberry family.

These plants are widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, with most species in Asia, others in Europe, northern Africa, and North and Central America. Only a single species occurs in the Southern Hemisphere.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek akros (‘sharp’ or ‘pointed’), alluding to the shape of the leaves.

Acer pensylvanicum Striped maple

This small tree, also known as moose maple, grows to about 10 m tall. It ranges from Nova Scotia and northern Quebec southwards along the Appalachian Mountains to northern Georgia. It is also found at scattered locations westwards to Michigan and Saskatchewan, and in Ohio.

The popular name stems from the striped bark on younger trees.

Autumn leaves of striped maple are of a warm yellow colour, here photographed at Williamsburg, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acer rubrum Red maple

Especially gorgeous is the autumn foliage of the red maple, which may display crimson, orange, and yellow on a single leaf. This species, also known as swamp maple, water maple, or soft maple, is one of the most abundant and widespread broad-leaved trees in eastern and central North America, distributed from Newfoundland southwards to Florida, and westwards to Manitoba, Minnesota, and eastern Texas.

It is very adaptable, growing in various types of soil, from swamps to dry areas, and from sea level to about 900 m altitude.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ruber (‘red’).

Autumn forest of red maple and sugar maple (see below), near Cummington, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Autumn foliage of red maple, Caleb Smith State Park, Long Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wine-coloured and yellow leaves on a red maple, Gorham, New Hampshire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flaming red and yellow leaves of red maple, Catskills (top) and Adirondacks, New York State. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acer saccharum Sugar maple

As its name implies, this tree, also known as rock maple, is an important source of sugar, utilized to produce the celebrated maple syrup. It is distributed from Nova Scotia westwards to Minnesota, southwards to Missouri and Tennessee, and thence north-east to New York State.

It is generally believed that the leaf of sugar maple is depicted on the Canadian national flag, but according to the website canada.ca/en.html, this depiction does not represent any particular maple species.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sugar’, adapted from Ancient Greek sakkharon, ultimately from Sanskrit sarkara, a term used for ground as well as candied sugar.

Wonderful foliage display of sugar maple and red maple in the Catskills, New York State. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mixed deciduous forest, dominated by sugar maple, with a few red maples (the scarlet trees), near Williamstown, Massachusetts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Due to its gorgeous foliage display, sugar maple is often planted near houses, as in these pictures from Silver Lake, New Hampshire (top), and Great Barrington, Massachusetts. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foliage of sugar maple adorns a stone wall near Gorham, New Hampshire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Similar to red maple, leaves of sugar maple often display several colours on a single leaf, in this case near Gorham, New Hampshire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

West American autumn foliage

Although eastern North America takes the prize, the western part of the continent also has a significant display of autumn colours, as is obvious from the following pictures.

Anacardiaceae Sumac family

Toxicodendron

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Toxicodendron diversilobum Western poison oak

Despite its name, this species, formerly known as Rhus diversiloba, is not even distantly related to oaks, and the name was given due to the similarity of its leaves to oak leaves. It is very common along the Pacific Coast, from British Columbia southwards to Baja California.

As with other members of this genus, poison oak contains a toxic substance, urushiol, which many people are allergic to (see poison ivy above, in section East American autumn foliage).

In his book My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) says: “Poison oak (…) is common throughout the foothill region up to a height of at least three thousand feet [900 m] above the sea. It is somewhat troublesome to most travelers, inflaming the skin and eyes, but blends harmoniously with its companion plants. (…) I have oftentimes found the curious twining lily (Stropholirion Californicum) climbing its branches, showing no fear but rather congenial companionship. Sheep eat it without apparent ill effects; so do horses to some extent, though not fond of it, and to many persons it is harmless. Like most other things not apparently useful to man, it has few friends, and the blind question, “Why was it made?” goes on and on with never a guess that first of all it might have been made for itself.”

The specific name is derived from the Latin diversus (‘diverse’), and Ancient Greek lobos (‘lobe’), referring to the leaves.

Autumn foliage of western poison oak, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fabaceae Pea family

Cercis Redbud, Judas tree

A small genus with about 10 species, found in temperate and subtropical areas of North America, Mexico, southern Europe, and Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kerkis, meaning ‘weaver’s shuttle’, applied by Greek scholar Theophrastos (c. 371 – c. 287 B.C.) to the Mediterranean Judas tree (C. siliquastrum). Presumably, shuttles were made from the wood of this species.

Cercis occidentalis California redbud

This small tree, which grows to 6 m tall, can be identified by its almost circular leaves. It is found mainly in northern California, less abundantly in southern California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona.

Early in spring, it produces a profusion of pink or purplish flowers.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the West’.

Autumn foliage of California redbud, near McArthur, Cascade Range, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fagaceae Beech family

Quercus Oak

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Quercus kelloggii California black oak

Found mainly in northern California and western Oregon, this tree grows in foothills and lower mountains. Its occurrence in southern California and Baja California is patchy, but it is common in the Sierra Nevada. Most trees live between 100 and 200 years, but some specimens have been known to be almost 500 years old.

This species is adapted to fire, protected from smaller fires by its thick bark. It is killed by larger fires, but easily sprouts again from the roots. Acorns mainly sprout, when a fire has cleared an area of leaf litter. This was known by several indigenous peoples, who purposely lit fires to renew growths of this tree, whose acorns was a staple food source to them.

The specific name honours American physician and botanist Albert Kellogg (1813-1887), one of the founding members of the California Academy of Sciences.

Leaves of California black oak are deeply cleft, 10-20 cm long. These pictures were taken near McArthur, Cascade Range (top), and in Kings Canyon National Park, Sierra Nevada. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rosaceae Rose family

Fragaria Strawberry

A genus with about 23 species of herbs, native to temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere and western South America. The fruit is highly distinctive, having a swollen, fleshy, red receptacle with tiny dry nuts on the surface.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for strawberry. The English name is derived from the verb to strew, in allusion to the dense tangle of the plant’s stems, creeping over the ground.

A number of strawberry species are presented on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Fragaria chiloensis Beach strawberry

This evergreen plant is native to the Americas, in North America found along the Pacific coast, from British Columbia southwards to California, in South America along the coasts of Chile and Argentina. Inland, it occurs in Bolivia.

It may grow to 30 cm tall, but is usually lower. The trifoliate leaves are thick, glossy green, leaflets to about 5 cm long. The stems are densely hairy, and also sometimes the leaf margin. The fruit is edible.

The specific name refers to Chiloë, an island in Chile. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

Autumn foliage of beach strawberry, John Dellenback Trail, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Physocarpus Ninebark

This genus contains at least 7 species, most of which are native to North America, with a single species in north-eastern China and Korea.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek physa (‘bladder’) and karpos (‘fruit’), referring to the inflated seed pods.

Physocarpus capitatus Pacific ninebark

A deciduous shrub, growing to 2.5 m tall, with reddish-grey bark, which peels off in several thin layers – hence the common name. The leaves are usually maple-like, palmately lobed, to 14 cm long and broad, margin double-toothed. They turn reddish, orange, or yellow in autumn. Inflorescences are clusters of small, creamy-white flowers, stamens with a red tip. The fruit is a tiny pod, to about 6 mm long, which is initially glossy-red, turning brown when ripe.

It occurs along the North American Pacific coast, from southern Alaska southwards to California.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘head’, alluding to the round flower clusters.

Autumn leaves and ripe fruits of Pacific ninebark, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Salicaceae Willow family

Populus Poplar, cottonwood, aspen

This genus contains about 60 species of deciduous trees, some majestic, to 50 m tall, with a trunk diameter to 2,5 m. They are native to the major part of the Northern Hemisphere, from subarctic regions southwards to Mexico, northern Africa, Iran, the Himalaya, and China, and also to East Africa.

The leaves are broad, with a long, slender stalk, which is flattened, making it rustle in the slightest puff of wind. Inflorescences are pendent catkins, with numerous tiny flowers clustered around a central axis, each flower surrounded by papery bracts. The flowers are wind-pollinated, and the fluffy seeds are spread by the wind.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for poplars. The common name cottonwood alludes to the fluffy seeds. The name aspen is derived from aspo, the ancient Proto-Germanic name of poplars.

Populus tremuloides Quaking aspen

In autumn, the foliage of quaking aspen adds vivid splashes of yellow to numerous areas in western North America. This species also has many other names, including golden aspen and trembling poplar. It is the most widely distributed tree in North America, found from Alaska southwards through western Canada and the United States to central Mexico, and in a broad belt across Canada and northern U.S. to Newfoundland and New England, southwards to Pennsylvania.

This tree was named for its leaves, which tremble noisily in the slightest breeze. The Onondaga people called it nut-kie-e, meaning ‘noisy leaf’, and a local poplar species in Louisiana was dubbed langues de femmes (‘women’s talk’) by the French refugees.

The specific name means ‘resembling tremula‘. It refers to the European aspen (P. tremula), presented below in the section European autumn foliage.

Quaking aspens on a mountain slope near Conway Summit, Sierra Nevada, California. The second picture shows the snow-white trunk of this iconic species. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sapindaceae Soapberry family

Acer Maple

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Acer circinatum Vine maple

This species is usually a shrub, but may grow to a small tree, sometimes reaching a height of 20 m. The common name probably stems from its short, crooked trunk, with twisted, spreading limbs, which somewhat resemble those of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera).

It has a rather limited distribution, found along the Pacific coast from southern British Columbia southwards to northern California, being a colonizer of avalanche areas and open forests, which have been clear-cut by loggers.

In former days, wood of this tree was utilized by native tribes to make bows, frames for fishing nets, snowshoes, and cradle frames. Other tribes boiled the bark of the root and drank this decoction to treat colds. Charcoal made from this species was mixed with water, taken against dysentery and polio.

Yellowish, wine-red, and orange-red autumn foliage of vine maples, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf maple

As its name implies, this species, also known as Oregon maple, has large leaves – in fact the largest leaves of any maple, often to 30 cm across, with five deeply indented lobes.

Most individuals of this tree are 15-20 m high, but specimens up to 48 m tall have been recorded. It is native to the Pacific Coast, from southernmost Alaska to southern California. Inland, it occurs in the Sierra Nevada, and in central Idaho.

Autumn foliage of bigleaf maple is yellow. This picture shows a large, moss-covered specimen, encountered at the North Umpqua River, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leaves of a bigleaf maple, illuminated by a patch of sunshine, Humboldt Redwood State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

European autumn foliage

Compared to the marvellous autumn colours in North America, autumn in Europe is a more subdued affair. However, a number of plants do have gorgeous autumn foliage.

Betulaceae Birch family

Betula Birch

A genus with 50-60 species, distributed in temperate and subarctic areas of Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Male and female flowers are borne in catkins, in separate inflorescences, males pendulous, females erect. The fruit fragments into 3-lobed scales and winged nutlets when mature.

The generic name is derived from Celtic betu (’glue’), referring to the fact that Celts extracted a glue-like substance from birch sap. In certain areas with Gaelic-speaking peoples, including Wales and Brittany, birch is still called bezuenn or bedwen.

The common name is derived from Proto-Germanic berko, in all probability rooted in Sanskrit bhurja, the name of a species of birch.

In Norse religion, the birch represented Freya, the Great Mother Goddess, and among Celtic peoples the star goddess, Arianrhod, whose caer (‘throne’) was situated in the Corona Borealis (Northern Lights). She was invoked through the birch to assist in births and initiations.

Previously, the soft birch wood was carved into numerous items, including furniture, cups, bowls, bobbins, cradles, and toys. The bark separates into thin strips, which peels off easily. It is tough, water proof and rot proof, making it perfect as roofing material. It was also utilized to make buckets, baskets, bottles, plates, and shoes, and for writing and drawing. Due to its content of volatile oils, rolled-up bark could be used as torches.

Betula nana Dwarf birch

As its name implies, this species is small, rarely growing taller than 1.2 m. It has a circumpolar distribution, mainly found in the Arctic. At the southern limits of its range, such as Scotland and the Alps, it is restricted to mountains. In the latter area, it grows up to an altitude of 2,200 m.

In Scotland, many populations have declined drastically in recent years, presumably due to global warming.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘dwarf’.

In Iceland, dwarf birch is very common, here photographed at Jökulsá á Fjöllum River (top), and on the mountain Fornastaðafjall, near Akureyri. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula pendula Silver birch

This tree is widespread and common from Europe and the Caucasus eastwards across Siberia to the Pacific, and thence southwards to northern China and Japan.

The specific name means ’pendulous’ or ‘hanging’ in Latin, referring to the pendulous outer branches of this species.

Autumn foliage of silver birch, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen leaves of silver birch, forming a carpet, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betula pubescens Downy birch

Like silver birch, this species is widespread and common in Europe and the Caucasus, and thence eastwards across Siberia to the Pacific.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pubes (’downy’), like the common name alluding to the downy twigs of this tree.

In former days, birch populations in Arctic regions were regarded as a subspecies, tortuosa, of the downy birch. However, genetic research indicates that it evolved from hybridization between downy birch and dwarf birch, and today most authorities regard it as a variety of the former, named B. pubescens var. pumila.

An old downy birch, displaying autumn foliage, Ismanstorp, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Millions of years ago, volcanic activity in today’s northern Iceland brought fluid basaltic lava to the surface, where it formed a plateau. As the lava cooled, it contracted and fractured in a similar way to drying mud. As the lava cooled further, these cracks penetrated downwards, forming 6-sided (sometimes 4-, 5-, and 7-sided) columns. Further volcanic activity since pushed some of the columns into a horizontal position.

Some of these formations, named Hljoðaklettar, have withstood erosion by the Jökulsá á Fjöllum River. Hljoðaklettar means ‘Echo Rocks’, so named due to the peculiar acoustics of the area, which produce echoes.

Autumn foliage of arctic downy birches adds a touch of colour to the otherwise sombre Hljoðaklettar rocks. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Celastraceae Staff-tree family

Euonymus Spindle tree, burning-bush

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Euonymus europaeus European spindle tree

This small tree is found in the major part of Europe, eastwards to Ukraine and the Caucasus. The wood of this species is very hard and was formerly used to make butchers’ skewers and spindles for wool-spinning, hence its common name.

The gorgeous fruits are red, pink, or purplish capsules, opening late in the autumn to reveal the black seeds, which are coated with a fleshy orange layer. They are shown below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits. They look very inviting indeed, but the seeds contain highly toxic alkaloids, and several cases of poisoning of children have been reported.

A close relative, the eastern burning-bush (E. atropurpureus), is presented above in the section East American autumn foliage.

Autumn foliage of spindle tree, southern Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cornaceae Dogwood family

Cornus Dogwood

The only genus of the family, containing about 55 species, which are widespread in northern temperate areas, with a single species in tropical Africa and one or two in South America. The flowers are in heads or flat-topped clusters, in some species with large, coloured bracts.

The generic name is derived from the Latin cornu (‘horn’), alluding to the hard wood of Cornelian cherry-dogwood (Cornus mas). It is so dense that it will sink in water.

The prefix dog may imply that the fruits of common dogwood (below) are of little value, having a bitter taste. Alternatively, it may refer to the former usage of dogwood shoots, which were sharpened and used by farmers as cattle prods, called dags. Skewers were also made from the tough and durable wood.

Cornus sanguinea Common dogwood

This deciduous shrub, usually 2-3 m tall, occasionally up to 6 m, is native to the major part of Europe, from Ireland, Scotland, and southern Norway southwards to Spain, southern Italy and Greece, eastwards to western Russia, Ukraine, Turkey, and the Caucasus. Elsewhere, it is widely cultivated as an ornamental due to its reddish stems, which are quite showy, when the leaves have been shed.

In former days, oil from the berries was used as lamp fuel. Medicinally, they were utilized as an emetic, whereas the astringent bark was used as a febrifuge.

In 1991, the well-preserved body of a Stone Age hunter was discovered in a glacier in the Alps. Ötzi the Iceman, as he was dubbed, died about 5,300 years ago, presumably caught in a snowstorm. His arrow shafts were made from dogwood and viburnum wood. (Source: K. Spindler 1994. The Man in the Ice)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘blood-coloured’, which may refer either to the red stems or to the autumn foliage.

Raindrops hang like pearls on autumn leaves and fruits of this common dogwood, Valle Teña, Aragon, Spain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dennstaedtiaceae

Pteridium

This genus contains about 18 species, distributed almost globally, with the exception of polar regions.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pteris (‘fern’) and ium, a suffix forming adjectives.

Pteridium aquilinum Bracken

Originally, bracken was native to temperate and subarctic areas of Eurasia, and from northern Africa eastwards across the Middle East to Iran, with disjunct populations in Ethiopia and Yemen. However, it has since spread to all continents, except Antarctica. It readily invades abandoned fields and pastures, where it can cover huge areas, prohibiting growth of other species.

The specific name is derived from the Latin aquila (‘eagle’). Dutch philosopher and theologian Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (1466-1536), in English known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, said that the pattern of the fibres seen in a transverse section of the leaf-stalk resembled a double-headed eagle, and in 1755, in his reprint of Flora Suecica, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) explains that the name refers to the image of an eagle, seen in the transverse section of the root.

Autumn foliage of bracken attains a lovely golden colour. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ericaceae Heather family

Vaccinium Blueberry, bilberry, and allies

A huge genus with about 450 species of shrubs or shrublets, found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, and also in tropical mountains of Asia and Central and South America, and a few species in Africa and on Madagascar.

Blueberry is the name of 21 small shrubs of this genus, 20 of which are indigenous to North America, including the European blueberry (below). The remaining species, Korean blueberry (V. koreanum), is restricted to Korea and the neighbouring Liaoning Province of China.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of blueberries.

Vaccinium myrtillus European blueberry, common bilberry

This dwarf shrub is abundant on acidic soils in the major part of Europe, southwards to the Mediterranean, in northern and central Asia, eastwards to Japan, and in western North America.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek myrtos (‘myrtle’), and the Latin illus, a diminutive suffix, thus ‘the small myrtle’, alluding to the myrtle-like leaves.

A picture, depicting the delicious fruits, is shown below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

Autumn foliage of European blueberry, Jutland, Denmark (top), and Byrums Sandfelt, Öland, Sweden. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vaccinium uliginosum Bog bilberry

Another dwarf shrub with an enormous distribution, found in temperate and subarctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere, besides isolated populations in montane areas, including the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Caucasus in Europe, the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains in North America, and mountains in Mongolia, China, Korea, and Japan.

The berries resemble those of European blueberry, but have a slightly acidic taste. They are depicted below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

The specific name is derived from the Latin uligo (‘dampness’), referring to the fact that the prime habitat of this species is swampy areas.

This large growth of bog bilberry, growing in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Jutland, Denmark, displays a fantastic reddish-purple autumn foliage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A recent shower has adorned the red autumn foliage of this bog bilberry with countless ‘pearls’. – Fornastaðafjall, near Akureyri, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fagaceae Beech family

Fagus Beeches

Beeches, comprising between 10 and 13 species of trees, are native to temperate and subtropical areas of Europe, Asia, and North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for beeches.

Fagus sylvatica European beech

This large tree, which may occasionally grow to 50 m tall, is largely restricted to Europe, occurring from England and the Pyrenees eastwards to Poland and Ukraine, and from southern Sweden southwards to Italy and the Balkans, with a patchy occurrence in southern Norway, central Spain, and Turkey. In the Balkans, it hybridizes with the oriental beech (F. orientalis).

The specific name is derived from the Latin silva (‘forest’) and aticus (‘pertaining to’), thus ‘growing in forests’.

Other pictures, depicting this tree, are shown on the pages Plants: Ancient and huge trees, and Nature: Nature’s patterns.

Autumn forest, dominated by beech, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Large specimens of European may have a trunk diameter of up to 3 m. – These were photographed in Zealand, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cyclists in a foggy beech forest, Jægerspris, Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Autumn foliage of beech, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Autumn foliage of beech, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fallen leaves of beech create a carpet, Funen, Denmark. The yellow leaves are common hazel (Corylus avellana), the smaller green ones goat willow (Salix caprea). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beech leaves, and a few leaves of common elm (Ulmus glabra), have fallen into a moat, Nyborg Castle, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Quercus Oak

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Quercus robur Common oak

Common oak, also known as English oak or pedunculate oak, is native to the major part of Europe, eastwards through Turkey to the Caucasus and northern Iran.

The specific name is Latin, originally meaning ‘reddish’, but later also ‘strong’ or ‘hard’, referring to the hard, dark heartwood of the common oak.

Other pictures, depicting common oaks, may be seen on the pages Plants: Ancient and huge trees, and Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Autumn foliage of common oak, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Malvaceae Mallow family

Tilia Linden, basswood, lime tree

Members of this genus, comprising about 30 species of trees or large bushes, are native to temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere, with the greatest diversity in Asia. Previously, they were placed in a separate family, Tiliaceae, which has now been included in the mallow family.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tilos (’fibre’), referring to the use of the bark as bast. The name linden was adopted from the old Norse name of the plant, lind. In Britain, linden trees are sometimes called lime, probably a corruption of lind.

In prehistoric times, linden trees were sacred to many Germanic and Slavic tribes. In the Norse religion, they were dedicated to Odin’s wife Frigg, goddess of wisdom and foreknowledge. Later, lindens were worshipped as a symbol of knowledge, often planted in the centre of the village, where the elders would meet to discuss various issues.

Due to their content of essential oils, linden flowers emit a powerful fragrance, and tea made from dried flowers is a popular drink in many countries, in France called tilleul, in Italy tiglio, and in the Unites States basswood tea. The flowers supply excellent honey, and during the Middle Ages, linden trees were often planted around monasteries and castles to provide honey.

The role of linden trees in folklore and folk medicine is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Tilia × europaea Common linden

This natural hybrid between small-leaved linden (T. cordata) and large-leaved linden (T. platyphyllos) is widely cultivated, and has also become naturalized at scattered locations across Europe.

Autumn foliage of linden trees is of a warm yellow colour. These pictures show common linden trees and fallen leaves at Jægerspris, northern Zealand, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oleaceae Olive family

Fraxinus Ash

These trees, comprising about 58 species, are widespread in temperate and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere, and some species also occur in tropical areas of Mexico, Central America, Indochina, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

The generic name is derived from Proto-Italic fraksinos, originally a Proto-Indo-European word for birch trees. The connection to birches is hard to see.

Fraxinus excelsior Common ash

A common tree, native to almost the entire Europe, eastwards to the Caucasus and the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran. It has also become naturalized a few places in New Zealand, the United States, and Canada.

In later years, populations of ash have been much reduced by ash dieback, a disease caused by a fungus, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, previously called Chalara fraxinea. Most trees that contract this disease die after a few years. However, research has shown that some trees have resistance to it.

The specific name is derived from the Latin excelsus (‘lofty’) and ior, a suffix forming adjectives.

Autumn foliage of common ash, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhamnaceae Buckthorn family

Frangula

A genus with about 56 species, distributed in the entire Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, western and central Siberia, China, Korea, Japan, Indochina, and the major part of the Americas.

The generic name is Latin, meaning fragile, originally from frango (‘to break’), referring to the fragile branches of alder buckthorn (below).

Frangula alnus Alder buckthorn

This deciduous shrub, growing to 7 m tall, is distributed from the British Isles and Scandinavia eastwards to central Siberia and Xinjiang, southwards to Morocco, Turkey, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains in northern Iran. It mainly grows in humid, open habitats.

The specific and common names refer to the fact that alder buckthorn often grows in the same places as common alder (Alnus glutinosa).

Multi-coloured leaf of alder buckthorn, Thy, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rosaceae Rose family

Prunus Cherry, plum, sloe

A huge genus with around 340 species of deciduous trees or shrubs, distributed across the globe, except in polar regions, Australia, and some desert areas of Africa.

The fruit is a drupe, with a fleshy outer layer and an inner hard stone, enclosing the seed.

The generic name is a Latinized version of the Ancient Greek name of the plum tree, prounos.

The common name cherry, like the German Kirsch and the Italian cerasa, stems from the Latin cerasus, which was adopted from kerasos, the classical Greek name of the cherry tree. Cerasus was also the ancient Roman name of the modern town Giresun, situated on the Black Sea coast of Turkey, from where cherries during the Roman Era were exported to Rome.

Cherry species are dealt with in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Prunus avium Wild cherry

The native area of wild cherry was probably from France across Europe to the Caucasus. Originally, this species was not indigenous in northern Europe. Excavations in kitchen middens indicate that it was introduced during the Viking Age, and it has not been found in older middens. Today, it is very commonly naturalized in Denmark and southern Sweden.

The specific name is derived from the Latin avis (‘bird’), relating to the fact that various bird species love cherries. The delicious fruit is shown in a picture below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

Most autumn leaves of cherry trees are a lovely yellow. These pictures show a border terrier pup and a kitten, surrounded by fallen leaves of a large cherry tree, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Autumn foliage of wild cherry may also be various shades of red. – Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Some individuals of wild cherry display brownish autumn foliage, like this specimen in Zealand, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rubus Bramble, raspberry, and allies

This huge genus, comprising more than 1,400 species of prickly shrubs or creeping shrublets, is found all over the globe, except in Antarctica and certain deserts and tropical forests.

The fruit is highly distinctive, a globular head on the domed tip of the flower-stalk, consisting of fleshy carpels, usually with many nutlets on the surface.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for bramble (below).

Rubus caesius Dewberry

This species has a very wide distribution, from Scandinavia southwards to the Mediterranean, and from Ireland across Europe and western Asia to Xinjiang. It has also become naturalized in various other countries, including Canada, the United States, and Argentina. Its autumn foliage is a lovely crimson or wine-red.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘blue-grey’, alluding to the colour of the fruits (see section Berries and berry-like fruits below).

In Denmark, where these pictures were taken, dewberry is abundant in open forests, shrublands, and fallow fields. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rubus fruticosus Bramble

This species, also known as R. plicatus, is very variable, especially as regards the size and number of thorns on the stem, and the leaf shape. It is widely distributed in northern and central Europe, but has been introduced to many other countries.

It is highly invasive in some areas, forming dense thickets, which expel native vegetation and often threaten entire ecosystems. It is considered a noxious weed in many countries, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shrubby’.

A picture, depicting the delicious fruits, is shown below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

Bramble, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Salicaceae Willow family

Populus Poplar, cottonwood, aspen

See section West American autumn foliage above.

Populus tremula European aspen

This large tree, sometimes growing to 40 m tall, is native to Eurasia, found from subarctic areas in Iceland, Scandinavia, and northern Russia, eastwards to Kamchatka, southwards to Spain, Turkey, the Tian Shan Mountains of Central Asia, and northern Japan. In the southern parts of its range, it is restricted to high altitudes in mountains.

The specific name is derived from the Latin tremo (‘shaking’, ‘quaking’, ‘quivering’), and the suffix ulus, which denotes something small.

Autumn foliage of European aspen, Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sapindaceae Soapberry family

Acer Maple

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Acer platanoides Norway maple

As its name implies, Norway maple is native to Europe, found from southern Scandinavia southwards to the Pyrenees, Italy, and the Balkans, eastwards to Ukraine, and thence southwards to the Caucasus and Turkey.

It has also been introduced to North America, where it has become invasive in many eastern states. For this reason, Massachusetts and New Hampshire have banned planting of it.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘resembling Platanus‘, alluding to the leaf shape, which resembles that of plane trees (below).

Autumn leaves of Norway maple assume all colours between pale yellow and orange, as seen in these pictures from Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acer pseudoplatanus Sycamore maple

A native of Central Europe, this tree was introduced to Britain around 1500, and it has also become naturalized in other parts of Europe, and in Australia, New Zealand, and North America. In many places, it has become an invasive, easily spreading by its winged seeds, which are produced in the tens of thousands on a single large tree.

An example of this invasiveness is described on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Expanding wilderness.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘false Platanus‘, alluding to the leaf shape, which resembles that of plane trees (below).

These fallen leaves of sycamore maple display three colours, reddish, yellow, and greenish. – Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ulmaceae Elm family

Ulmus Elm

This genus, comprising about 38 species, is widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, and also found in Indonesia.

The fruit is a nutlet, surrounded by a wide, papery wing, to 1.5 cm across.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for elms.

Ulmus glabra Common elm

This large tree, sometimes growing to 40 m tall, is also called wych elm, Scotch elm, or Scots elm. It is found in the major part of Europe, eastwards to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus, and the Alborz Mountains of northern Iran.

In Europe, populations of common elm have been drastically reduced by Dutch elm disease, described in depth on the page Nature Reserve Vorsø: Dutch elm disease on Vorsø.

Young fruits of this species are edible.

The name wych is from an Old English word, wice, meaning ‘pliable’. The specific name means ’smooth’ in Latin, referring to the smooth branches on younger trees.

The leaves of common elm have a very rough surface. These pictures are from Zealand, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Viburnaceae Viburnum or moschatel family

In the past, the genera Sambucus and Viburnum constituted the family Sambucaceae, but were then transferred to the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae), and later to the moschatel family (Adoxaceae), which is today called Viburnaceae.

Sambucus Elder

The number of elder species is disputed, and there may be anywhere between 25 and 50. These trees, shrubs, or shrubby herbs are distributed in temperate and subtropical areas, mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, with some members in parts of Australasia and South America.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sambuca, the term for an ancient instrument of Asian origin. Presumably, the soft pith was removed from the twigs to make flutes. The name elder is derived from Anglo-Saxon aeld (’fire’). The hollow stems were used to kindle a fire.

Sambucus nigra Common elder

Common elder is native to Europe and North Africa, eastwards to the Caucasus, and has also become naturalized in North America.

The popular names pipe tree and bore tree stem from the habit of removing the pith of elder branches to produce pipes. The same procedure would make pop-guns, which were popular among small boys. English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) writes: ”It is needless to write any description of this, since every boy that plays with a pop-gun will not mistake another tree for the elder.”

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘black’, alluding to the colour of the berries (see section Berries and berry-like fruits below).

The role of elder in folklore and traditional medicine is described in depth on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

Autumn colours of elder leaves is usually a subdued affair, but occasionally they may display brilliant colours, like this specimen in eastern Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vitaceae Grapevine family

Vitis Grapevine

This genus, comprising about 80 species, is found in the Americas, from eastern Canada southwards to northern South America, in central and southern Europe, from the Middle East eastwards to Japan and south-eastern Siberia (Ussuriland), and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common grapevine (below), originally from Proto-Indo-European wehitis (‘the one that twines or bends’).

Vitis vinifera Common grapevine

Presumably, this plant was originally native to central and southern Europe, and from the Middle East eastwards to Kyrgyzstan. In all probability, it was first cultivated in Asia Minor, at least 6,000 years ago.

In Greek mythology, Dionysos was originally the god of nature, and especially plants, but was later regarded as god of wet elements, in particular wine and blood. Initially, the major part of his followers were women, who, clad in animal skins and wearing wreaths of ivy (Hedera helix), wandered into the woods, carrying snakes and long lances with garlands of ivy, and a cone from stone pine (Pinus pinea) pierced at the point. Accompanied by music from whistles and tambourines, they danced themselves into an ecstatic frenzy, during which they believed that they saw milk, wine, and honey flow from Dionysos’s mouth. They caught wild animals, drank their blood, and wrapped their skins around their bodies. The were possessed by madness, mania, and were therefore called maenads (literally ‘the raving ones’).

The specific name is derived from the Latin vinum (‘wine’) and fer (‘carrying’).

Autumn foliage of grape vine, Funen, Denmark. The plant with red stems is white dogwood (Cornus alba). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Asiatic autumn foliage

As in Europe, autumn colours in Asia are generally not as brilliant as in America, although a number of species do attain very beautiful fall foliage. In many warmer areas, the ‘autumn’ colours appear in the winter months. A number of these winter foliage species are also presented here.

Altingiaceae

Liquidambar Sweetgum

See section East American autumn foliage above.

Liquidambar formosana Chinese sweetgum

This large tree, growing to 40 m tall, is easily identified by its three-lobed leaves, which are almost entire, unlike the usually five-lobed leaves of most Asian maple species (see Sapindaceae below), which are strongly toothed.

Chinese sweetgum is mainly found in warmer temperate climates, growing in forests as well as in open areas. It is native to central and southern China, Taiwan, and Indochina. It is often used in traditional medicine, the bark for skin diseases, the resin for boils, toothache and tuberculosis, and the fruits for a number of ailments, including arthritis, lumbago, and skin diseases. It seems that leaves and roots can inhibit growth of cancer.

A close relative, American sweetgum (L. styraciflua), is presented above in the section East American autumn foliage.

The specific name is from the Portuguese formosa (‘beautiful’), a word that they applied to Taiwan, when they occupied the island. Most species, which bear variants of this name, were described from material stemming from Taiwan.

Chinese sweetgum is very common in Taiwan. These trees with red winter foliage were encountered in the city of Taichung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the angular, three-lobed leaves, Dasyueshan National Forest, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anacardiaceae Sumac family

Pistacia Pistachio trees

This genus, comprising about 11 species, is native to southern Texas, Mexico, Central America, southern Europe, northern and eastern Africa, and from the Middle East eastwards to China, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the true pistachio tree (P. vera), adapted from Ancient Greek pistakia.

Pistacia chinensis Chinese pistachio tree

This small tree is native from Afghanistan eastwards to China and Taiwan, and thence southwards to the Philippines. A disjunct population is found in the Caucasus.

Due to its hardiness, and the attractive autumn foliage, it is widely cultivated in temperate and subtropical areas around the world. In warmer areas, it sheds the leaves in mid-winter.

Chinese pistachio tree is very commonly planted along streets in Taiwanese cities. These pictures from Taichung show the red winter foliage of this species. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Begoniaceae Begonia family

Begonia

A huge genus with more than 1,900 species, found worldwide in warm, moist regions, in Asia alone more than 600 species. Male and female flowers are quite different, the males having 4 petals, of which the outer two are rounder and broader than the inner ones. Female flowers have 5 or more petals, of almost equal size.

The generic name commemorates Michel Bégon (1638-1710), from 1684 governor of Saint-Domingue, a French colony on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, today named Haiti. Bégon was a passionate plant collector.

Begonia picta

This plant can be identified by its hairy, irregularly double-toothed leaves, which are often blotched with purple. It is very common in the Himalaya, growing on moist rocks and banks, and in shady forest margins, at altitudes between 600 and 2,900 m, from Pakistan eastwards to south-eastern Tibet.

Leaf-stalk and stems are edible when pickled, and the plant is also widely used in local medicine. Juice of stem and leaves is taken for headache, and juice of the root is used for inflamed eyes and peptic ulcer. The juice is also squeezed into vegetable dyes to make them colourfast.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘painted’, referring to the blotches on the leaves.

Other pictures, depicting this plant, may be seen on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

Autumn foliage and fruits of Begonia picta, Upper Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Berberidaceae Barberry family

Berberis Barberry

A huge genus with about 620 species, widespread in the Americas and Eurasia, and also occurring in northern and eastern Africa and southern Arabia. The majority are small shrubs, which often form dense, impenetrable thickets due to their spiny stems, and in some species along the leaf-margins. They all have pretty yellow flowers, which later turn into red, blue, or blackish berries. The wood of some species yields a yellow dye. The autumn foliage of most species is a brilliant crimson.

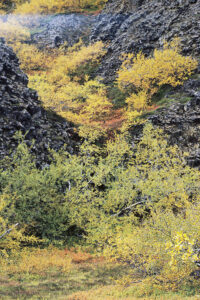

A picture, depicting autumn thickets of barberry, may be seen at the top of this page, whereas common barberry (B. vulgaris) is presented below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of barberry.

Berberis ceratophylla

This deciduous shrub in the Himalaya, to 2 m tall, is sometimes regarded as a subspecies of the similar B. aristata, which is much more common. The branches are greyish, grooved, with spines to 1.4 cm long, the leaves are oblanceolate or wedge-shaped, to 5 cm long, and the margin has many spines. The flowers are yellow, in many-flowered, branched clusters. The berry is oblong or ovoid, dark red or purple when ripe, to 1.2 cm long.

This species is found at elevations between 1,800 and 4,000 m, from Himachal Pradesh eastwards to Myanmar. In Nepal, the branches are used as fences, and the fruits are eaten raw or pickled.

A few leaves remain on the bush until next spring. They usually turn red or crimson in autumn or winter.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek keras (‘horn’) and phyllon (‘leaf’). What it refers to is not clear.

Crimson winter leaves of Berberis ceratophylla, Shivapuri-Nagarjun National Park, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Berberis concinna

This small, spiny bush, growing to 1 m tall, usually forms large thickets in open areas at high altitudes in the Himalaya, between 2,700 and 4,400 m. It is distributed from central Nepal eastwards to Sikkim and south-eastern Tibet.

The leaf margin is spiny, and the yellow flowers are solitary. The berry is dull red when ripe, to 1.6 cm long.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘neat’ or ‘elegant’, perhaps alluding to the delicate reddish-purple colour of the winter foliage.

Winter foliage of Berberis concinna assumes a delicate reddish-purple colour. – Magingoth, Langtang National Park, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Betulaceae Birch family

Betula Birch

See section European autumn foliage above.

Betula utilis Himalayan birch

This tree is easily identified by its reddish bark, which peels off in large flakes. It is very common from Afghanistan eastwards to China, growing at high altitudes.

In former times, this tree had multiple uses, reflected by the specific name, which is Latin for ‘useful’. The wood was utilized for buildings and as firewood, the bark as roof cover, to make paper, as incense, and in folk medicine for various ailments, and the foliage was lopped for fodder.

Himalayan birch is described in depth on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 1.

As in most other birches, autumn foliage of Himalayan birch is bright yellow, here photographed at the Bagah River, Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Combretaceae

Terminalia

A huge genus with about 280 species, widely distributed in warmer areas, from Mexico and Florida southwards to Argentina, in Africa south of the Sahara, southern Arabia, southern Asia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and eastern Australia.

The generic name is derived from the Latin terminus, ultimately from Proto-Italic termenos (‘boundary’), referring to the fact that the leaves appear at the very tip of the shoots.

Terminalia catappa Beach almond

The native area of this tree, also known as country almond, Indian almond, Talisay tree, and umbrella tree, is unknown. Today, it is widely distributed in most tropical and some subtropical areas of the world, growing in a wide range of habitats.

Three of the popular names stem from the similarity of its fruits to those of the true almond (Prunus amygdalus), but the two species are not even distantly related, as the true almond is a member of the rose family (Rosaceae).

The specific name is derived from its Malay name, ketapang.

A picture, depicting the fruit, is shown below in the section Berries and berry-like fruits.

Gorgeous winter foliage of beach almond. With the exception of the second picture from above, which is from Myanmar, all the images are from Taiwan, where this species is widely planted as an ornamental tree. The two bottom pictures show upper and lower surface of a leaf, respectively. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elaeocarpaceae

Elaeocarpus

This is a large genus with about 490 species of mostly evergreen trees or shrubs, with a few epiphytes and climbers. They occur in southern and eastern Asia, from India eastwards to Korea and Japan, southwards to Indonesia, New Guinea, eastern Australia, and New Zealand, on Madagascar, and islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek elaion (‘olive’) and karpos (‘fruit’), thus ‘with an olive-like fruit’.

Elaeocarpus serratus Ceylon olive tree

This tropical tree is native to the southern part of India and Sri Lanka, and also occurs in Assam and Bangladesh. Due to its wonderful winter foliage, it is commonly cultivated as an ornamental plant in Southeast Asia, southern China, and Taiwan.

In Sri Lanka, its fruit is a common food source, and it is also widely used in traditional medicine.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘sawn’, presumably referring to the teeth on the leaf margin.

Gorgeous winter foliage of Ceylon olive tree, Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Euphorbiaceae Spurge family

Euphorbia Spurge

A huge genus, comprising about 2,000 species of herbs, shrubs, or small trees, most with a milky sap, and some succulent and often spiny. The floral structure of these plants, the cyathium, is cup-like, consisting of fused bracts with nectary glands along the margin. These bracts are surrounding a ring of male flowers, each with one stamen, and a single female flower is in the centre. Together, these flowers resemble a single flower. The fruit is a capsule, with 3 valves.

King Juba II (c. 50 B.C. – 19 A.D.) of Numidia (in present-day Algeria and Tunisia) had an interest in plants and often described them, including a thorny, succulent plant from the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, whose latex was a powerful laxative. He named this plant Euphorbea in honour of his Greek chief physician, Euphorbus. In 1753, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) adopted this name, in the form Euphorbia, for the entire genus.

Euphorbia sikkimensis Sikkim spurge

This plant is very common in the Himalaya, from Nepal eastwards to south-western China, growing in meadows, shrubberies, and open areas between 2,400 and 4,500 m altitude. In Nepal, the root is used medicinally.

In autumn, the leaves of some specimens of Sikkim spurge turn bright red. This one was photographed in Langtang National Park, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Triadica

A small genus with only 3 species, found from India eastwards to Korea and Japan, and thence southwards to the Philippines and Indonesia.

The generic name is derived from the Latin triadis (‘a group of three’), originally from Ancient Greek trias (‘three’). The name refers to 3-parted flowers.

Triadica sebifera Chinese tallow-tree

This smallish tree, formerly called Sapium sebiferum, is native to China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and northern Vietnam.

The specific name means ‘wax-bearing’, referring to the tallow, which coats the seeds. Candles and soap are made from this wax, and in the Far East, the leaves are used in traditional medicine for treating boils. The sap and leaves are reputed to be toxic, and decaying leaves from the plant are toxic to other plants, inhibiting their growth.

Because of the tallow, this tree was introduced into the United States in the 1700s, and in the 1900s, it was widely planted along the Gulf Coast by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, in an attempt to establish a soap-making industry. However, it soon spread beyond control and is today regarded as a serious pest in south-eastern U.S., which expels native plant species.

The fruits are shown below in the section Fruits: Capsules.

In winter, the leaves of Chinese tallow-tree turn various gorgeous shades of red, varying from orange to wine-red. These pictures were all taken in Taiwan, where this species is very common. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colour variation among fallen leaves of Chinese tallow-tree, Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ginkgoaceae

Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo

German physician and botanist Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) lived in Japan 1690-92, working for the Dutch East Indian Company. During his stay, he noticed a tree with distinct bilobed leaves, which was often planted at palaces and temples, and along roads.

When he returned to Holland, Kaempfer brought seeds of this tree with him. In 1771, it was named Ginkgo biloba by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), after its Japanese name gin-kyo, which was used by Kaempfer. Thus, the last ’g’ must be a writing error, but due to the rules of botanical nomenclature we must accept Linnaeus’ blunder. Incidentally, gin-kyo means ‘silver apricot’, referring to the fruit, which somewhat resembles an apricot fruit.

British naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882) labelled ginkgo a ’living fossil’, a term he invented for species, which had survived unchanged for many millions of years. In fact, Ginkgo biloba is the sole surviving member of a group of plants, which evolved during Perm, more than 250 million years ago. It is so unique that it has its own division, Ginkgophyta, within the plant kingdom, with a single class, Ginkgoopsida, order Ginkgoales, family Ginkgoaceae, genus Ginkgo, and species biloba. Its nearest contemporary relatives are the cycads (Cycadales).

Ginkgo is very slow-growing, but can attain enormous dimensions, sometimes reaching a diameter of more than 4.5 m. The largest ginkgo in Japan, in Kita Kanegasawa, has a circumference of over 20 m. It often attains a height of more than 35 m, and an 1100-year-old specimen at the Yon Mun Temple in South Korea is 60 m tall. It is believed that ginkgo can live to an age of 2,500 years, or more.

Until the late 1900s, ginkgo was only known as cultivated, so it was quite sensational when larger populations were found on mountain slopes in eastern and south-western China. It is still debated, whether the eastern populations have been planted by monks, but is seems that the south-western populations are genuinely wild. (Source: C.Q. Tang et al. 2012. Evidence for the persistence of wild Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgoaceae) populations in the Dalou Mountains, southwestern China. American Journal of Botany 99 (8): 1408-1414)

The specific name refers to the bilobed leaves.

Autumn leaves of ginkgo are bright yellow. – Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Juglandaceae Walnut family

Pterocarya Wingnuts

A genus of large, deciduous trees with 6 species, all but the Caucasian wingnut (below) restricted to China and Japan. A Chinese species, which was previously called Pterocarya paliurus, has been transferred to a new genus and renamed Cyclocarya paliurus.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pteron (‘wing’) and karyon (‘nut’).

Pterocarya fraxinifolia Caucasian wingnut

This large tree, which may grow to 30 m tall, has pinnate leaves, which may be up to 60 cm long, with up to 27 leaflets. The inflorescences are catkins, male ones to 12.5 cm long, whereas female ones during fruiting may be up to 50 cm long.

It is native to the foothills of the Caucasus, and also to north-eastern Turkey and north-western Iran, but is widely cultivated elsewhere due to the beautiful foliage and the spectacular female catkins. It grows in clayey, mineral-rich soils, often with other deciduous trees like common alder (Alnus glutinosa) and white willow (Salix alba). It may form rather large shrubs, as it willingly shoots from roots and stumps.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with leaves like Fraxinus‘ (ash).

Yellow autumn foliage of Caucasian wingnut, cultivated in Kalmar Botanical Garden, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lythraceae Loosestrife family

Lagerstroemia Crepe myrtles

This genus, comprising about 50 species of trees and shrubs, is native from the Indian Subcontinent eastwards to China, Taiwan, and Japan, and thence southwards through Indochina, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Guinea to northern Australia, and some islands in the Pacific Ocean. Due to their beautiful flowers, many species are cultivated in numerous warmer areas.

The generic name was applied by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in honour of a Swedish merchant, Magnus von Lagerström (1696-1759), who was director of the Swedish East India Company. Lagerström was a keen naturalist, and despite never visiting Asia, he was able to procure many specimens from India and China, which he presented to Linnaeus. (Source: E. Bretschneider 1898. History of European Botanical Discoveries in China)

The fruit of crepe-myrtles is described below in the section Fruits: Capsules.

Lagerstroemia speciosa Giant crepe-myrtle

Also called Queen’s crepe-myrtle or Pride of India, this smallish tree usually grows to a height of about 15 m, some specimens reaching 25 m, with a trunk diameter of up to 60 cm. It is found in tropical and subtropical areas of Asia, from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to south-western China and thence southwards through Indochina, Indonesia, and the Philippines to New Guinea.

Due to its gorgeous inflorescences, it is widely cultivated as an ornamental tree. A substance, known as banaba, which is prepared from dried leaves in the Philippines, is used to treat diabetes and urinary problems. Elsewhere, a poultice made from the leaves is taken against malaria, and it is also applied to cracked feet. A decoction of the bark is used as a treatment against diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

This tree has a wide-spread root system, and it has been widely planted as a means to control soil erosion.

The specific name means ‘beautiful’ in Latin, derived from species (‘appearance’) and osus, a suffix forming adjectives.

Not only the flowers of crepe-myrtles are gorgeous. These pretty winter leaves of giant crepe-myrtle were photographed in city parks in Taichung, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meliaceae

Melia

This small genus, containing 3 species, is native to eastern Africa, southern and eastern Asia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and Australia.

The generic name is the Ancient Greek word for the ash-tree (Fraxinus). The genus was named due to the resemblence of the leaves to those of ash trees.

In Greek mythology, Melia was one of the Oceanids, daughter of the Titans Okeanos and Tethys.

Melia azedarach Persian lilac

This species, also known as Chinaberry, has bright yellow winter foliage. It is probably native to Iran and the Indian Subcontinent, but due to its beautiful flowers and fruits, it is widely planted elsewhere.

It readily becomes naturalized and is now regarded as an invasive species in several regions, including North America, East Africa, some Pacific Islands, New Zealand, and Australia.

Persian lilac is extensively planted in Taiwan. This picture shows its bright yellow winter foliage, photographed in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Moraceae Fig family

Broussonetia

A small genus with 4 species, found from India eastwards through Indochina to southern China, Korea, and Japan.

The generic name honours French naturalist Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet (1761-1807), who travelled in Spain, Morocco, the Canary Islands, and southern Africa. He then returned to France, where he became director of the botanical garden in Montpellier.

Broussonetia papyrifera Paper mulberry

This small tree is native to East and South Asia and possibly to some Pacific islands. It thrives in a wide range of habitats and climates, readily growing in disturbed areas. It is dioecious, spreading rapidly, when male and female plants grow together and seeds are produced. Birds and other animals eat the fruits and thus help dispersing the species.

Paper mulberry can also form dense stands via its spreading root system, and it is regarded as highly invasive in a number of countries, including Pakistan, Argentina, Ghana, and Uganda.

The specific and common names refer to the fact that the inner bark fibres have been utilized for paper making for more than a thousand years.

Other pictures, depicting this species, may be seen on the pages Nature: Invasive species, and Plants: Urban plant life.

Paper mulberry is very common in Taiwan, where this picture was taken. Occasionally, its foliage turns bright yellow in winter. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papaveraceae Poppy family

Meconopsis Himalayan poppies

These bristly beauties, counting about 95 species, are restricted to central and eastern Asia, occurring from northern Pakistan eastwards across the Himalaya, Tibet, and Qinghai to central and western China and northern Myanmar. They all contain yellow sap.

Hybridization in the genus is common, and many intermediate forms occur. Some species are cultivated as ornamentals in the West.