Antelopes

The male blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) is a wonderful creature, coal black, with white markings on face, legs and belly, and long, straight, spiralled horns. – Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Greater kudu (Strepsiceros strepsiceros) males have impressive spiralled horns. This picture shows a male of subspecies zambeziensis, with yellow-billed ox-peckers (Buphagus africanus) searching for skin parasites, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

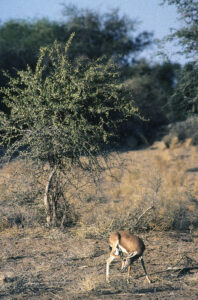

This male Kirk’s dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii ssp. cavendishi) is marking his territory with secretions from an eye gland, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgai males (Boselaphus tragocamelus), drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male impalas (Aepyceros melampus), Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Antelopes, comprising about 30 genera with around 90 species, are not a homogeneous or well-defined group. The term is used to describe all members of the family Bovidae, which are not cattle, sheep, goats, or goat-antelopes. The vast majority of antelopes are found in Africa, with a dozen species in Asia.

Genetic research in later years has had the effect that this family has been reorganized several times.

The word antelope stems from an ancient Greek word, antholops. According to Eustathius of Antioch (c. 336), this was the name of a fabulous animal “haunting the banks of the Euphrates, very savage, hard to catch and having long, saw-like horns capable of cutting down trees.”

One theory is that the name may derive from the Greek anthos (‘flower’) and ops (‘eye’), thus ‘flower-eyed’, perhaps referring to the beautiful eyes or long eyelashes of these animals.

On this page, the pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) is included, as one of its American names is American antelope, which is somewhat misleading, as it is not a true antelope, but forms a separate family, Antilocapridae.

Antelopes play an important role in the mythologies of certain African tribes. The following legend of the Bassari tribe in northern Togo, retold by German ethnologist and archaeologist Leo Viktor Frobenius (1873-1938) in Volksdichtungen aus Oberguinea (1924), describes the initial creations by the supreme anthropomorphic god Unumbotte:

“Unumbotte first made a human being, then an antelope, and then a snake. At the time these three were made there were no trees but one, a palm. Nor had the earth been pounded smooth. All three were sitting on the rough ground, and Unumbotte said to them: “The earth has not yet been pounded. You must pound the ground smooth where you are sitting.” Unumbotte gave them seeds of all kinds, and said: “Go plant these.” Then he went away.

Unumbotte came back. He saw that the three had not yet pounded the earth. They had, however, planted the seeds. One of the seeds had sprouted and grown. It was a tree. It had grown tall and was bearing fruit, red fruit. Every seven days Unumbotte would return and pluck one of the red fruits.

One day Snake said: “We too should eat these fruits. Why must we go hungry?”

Antelope said: “But we don’t know anything about this fruit.”

Then Man and his wife took some of the fruit and ate it.

Unumbotte came down from the sky and asked: “Who ate the fruit?” They answered: “We did.”

Unumbotte asked: “Who told you that you could eat the fruit?” They replied: “Snake did.”

Unumbotte asked: “Why did you listen to Snake?” They said: “We were hungry.”

Unumbotte questioned Antelope: “Are you hungry, too?” Antelope said: “Yes, I get hungry. I like to eat gras.” Since then, Antelope has lived in the wild, eating grass.

Unumbotte then gave sorghum to Man, also yam and millet. And the people gathered in eating groups that would always eat from the same bowl, never the bowls of the other groups. It was from this that the differences in language arose. And ever since then, the people have ruled the land.

But Snake was given by Unumbotte a medicine with which to bite people.”

The similarity of this legend to the Christian legend about the Fall of Man (related on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry) is striking. However, Frobenius points out that the Bassari legend was known to the tribe long before they came into contact with Christian missionaries.

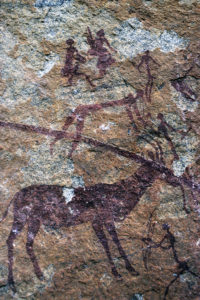

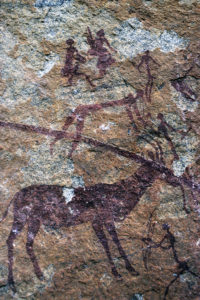

Rock painting near Ngomakirira, Zimbabwe, depicting hunters who pursue an impala (Aepyceros melampus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rock painting in the Nswatugi Cave, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe, depicts hunters, pursuing a male greater kudu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae

This subfamily contains 3 tribes, Bovini (cattle and buffaloes), Boselaphini (below), and Tragelaphini (below).

Tribe Boselaphini

A tribe with only two species, found in India and southern Nepal. Both are presented below.

Genus Boselaphus

Boselaphus tragocamelus Nilgai

This large, stout antelope, the only member of the genus, is distributed in the major part of India, and there is also a small population in southern Nepal. It is especially common in Rajasthan.

The name nilgai is Hindi, meaning ‘blue cow’, which refers to the slate-coloured, slightly bluish coat of the male, and to its similarity to the sacred cow. For the latter reason, the nilgai is protected by devout Hindus and has thus escaped the fate of many other animals in India, which are on the brink of extinction, such as the tiger (Panthera tigris), the lion (Panthera leo), and the blackbuck (below). The coat of females and young animals is a pale sandy brown. Both sexes have a white throat patch.

The scientific name of this antelope is quite peculiar. It is derived from four Greek words, bous (‘cow’), elaphos (‘deer’), tragos (‘goat’), and kamelos (‘camel’). The name was applied by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811), to whom this antelope apparently resembled a mixture of these four animals.

The slate-coloured, slightly bluish coat of the male nilgai, and its similarity to the sacred cow, have given rise to its name, which means ‘blue cow’ in Hindi. This bull was photographed in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cows and calves are pale brown with white chin and upper neck. Note the typical black-and-white markings on the ears. – Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, running across a swamp, Keoladeo National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting nilgai bull, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bull, greeting a young animal, Keoladeo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgais, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A cow and a younger animal, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. A rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) is sitting on the back of the young animal. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) are also present. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae, tribe Boselaphini, genus Tetracerus

Tetracerus quadricornis Four-horned antelope, chowsingha

This small antelope, the only member of the genus, stands only about 60 cm at the shoulder and weighs about 20 kg. It is the only wild bovid with four horns, of which the anterior pair, in the centre of the skull, is much smaller than the posterior pair. Only the male has horns.

These horns have given rise all names of this animal. The generic name is from the Greek tetra (‘four’) and keras (‘horn’), whereas the specific name is from the Latin quattuor (‘four’) and cornu (‘horn’). The Hindi name chowsingha is derived from chaar (‘four’) and siing (‘horn’).

Three subspecies have been described, quadricornis, which is distributed in most of the Indian Peninsula, subquadricornutus, which is found in southern India, and iodes, which is restricted to southern Nepal.

Female four-horned antelope, drinking from a waterhole in Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. Note the many bees around the animal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) and a crested bunting (Melophus lathami) are also present. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female at a waterhole, Sariska National Park. The birds are a white-browed fantail (Rhipidura aureola) and a crested bunting (Melophus lathami). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female with a kid at a waterhole in Sariska National Park. A northern plains langur (Semnopithecus entellus) is seen to the left. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae, tribe Tragelaphini

Members of this tribe are called spiral-horned antelopes. They comprise 5 genera, Ammelaphus, Strepsiceros, Taurotragus, and Tragelaphus (all presented below), and finally Nyala, with a single species, the lowland nyala (N. angasii).

Genus Ammelaphus

Ammelaphus imberbis Lesser kudu

Previously, this species was included in the genus Tragelaphus (below), but genetic research has concluded that it diverged from other members of this genus at an early stage, causing it to be transferred to a separate genus.

It is distributed from Ethiopia, Somalia, and South Sudan southwards to central Tanzania, living in shrubland and forested savannas. Two subspecies are recognized, the northern imberbis, and the southern australis.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ammos (‘sand’) and elaphos (‘deer’), thus ‘the deer that lives in sandy areas’. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘beardless’. This animal does not have a tuft of hairs on the neck as that of its larger cousin, the greater kudu (below).

Female lesser kudu, ssp. imberbis, Awash National Park, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female, ssp. australis, Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae, tribe Tragelaphini, genus Strepsiceros

Strepsiceros strepsiceros Greater kudu

This magnificent animal is widely distributed in eastern and southern Africa. Until recently, it was called Tragelaphus strepsiceros, divided into 3 subspecies. However, recent genetic research has caused it to be placed in a separate genus, with 4 subspecies:

The Cape greater kudu, ssp. strepsiceros, is restricted to southernmost South Africa.

The Zambezi greater kudu, ssp. zambeziensis, is found from southern Kenya southwards through eastern Africa to northern South Africa, and thence westwards to southern Angola and Namibia.

The northern greater kudu, ssp. chora, is distributed from Eritrea southwards to northern Kenya.

The western greater kudu, ssp. cottoni, lives in southern Chad and Sudan, and the northern parts of Central African Republic and South Sudan.

Male greater kudus have impressive spiralled horns, and for this reason they have been much persecuted by trophy hunters.

The generic and specific names are derived from Ancient Greek strepsis (‘inward turning’) and keras (‘horn’), alluding to the spiralled horns. The word kudu stems from Xhosa iqhude, which became koedoe in Afrikaans, and kudu in English.

Male Zambezi greater kudu, subspecies zambeziensis, Zambezi National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zambezi males, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zambezi male drinking, Etosha National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zambezi female with red-billed ox-peckers (Buphagus erythrorhynchus), searching for skin parasites, Krüger National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae, tribe Tragelaphini, genus Taurotragus

This genus contains only 2 species of huge antelopes, the common eland (below), and the giant eland (T. derbianus), which has a scattered occurrence in western and central Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tauros (‘bull’) and tragos (‘billy goat’), alluding to the cattle-like appearance of these animals, and to a tuft of hair in their ears, which resembles a goat’s beard. The common name eland is Dutch for the moose (Alces alces). It seems that to the Boer, who settled in South Africa in the 1700s, this antelope resembled a moose.

Taurotragus oryx Common eland

This species is the second-largest antelope in the world, an adult bull growing to 1.6 m tall and weighing up to almost a ton. Only the giant eland is slightly larger.

The common eland lives in woodland savanna and other types of grassland, sometimes forming herds of up to 500 animals. It is distributed from central Kenya, southern Zaire, and northern Angola southwards to the Cape province of South Africa.

The specific name is from the Greek orygos (‘pickaxe’), referring to the pointed horns of several African antelopes.

Herd of common eland, Hell’s Gate, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Common eland, Nairobi National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The tiny church in the village of Rondo, southern Tanzania, is adorned with a series of gorgeous stained-glass windows, depicting God’s creations, made by English artist and biologist Jonathan Kingdon (born 1935). The mammals are represented by an eland and a leopard (Panthera pardus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Bovinae, tribe Tragelaphini, genus Tragelaphus

A genus with 4 species, 3 of which are presented below. The fourth is the rare and elusive bongo (T. euryceros), which lives in dense forest.

The generic name alludes to a creature in Greek mythology, the tragelaph, from the Greek tragos (‘billy goat’) and elaphos (‘deer’), also called hircocervus, from the Latin hircus (‘billy goat’) and cervus (‘deer’) – a Chimera with the body of a stag and the head of a goat.

Tragelaphus buxtoni Mountain nyala

This large species, also known as balbok, is endemic to montane woodlands at an altitude of about 3000 m in the highlands of central Ethiopia, east of the Rift Valley, with more than half of the population in an area of c. 200 km2 in Bale Mountains National Park.

The male stands up to 135 cm at the shoulder, weighing up to 300 kg. Females are smaller, weighing up to 200 kg. The coat of the male is dark grey, with white patches on the throat and neck, and black and white markings in the face. Females are greyish brown.

This species was the last large antelope to be discovered in Africa, described as late as 1910. Major Ivor Buxton, who had been on a hunting trip to Ethiopia, brought a specimen to England in 1908, where it was described by naturalist Richard Lydekker (1849-1915), who gave it the specific name buxtoni in honour of the major.

The mountain nyala is endangered due to competition from large herds of cattle, which is brought into the mountains by human settlers.

The male mountain nyala is a magnificent animal, with large, spiralled horns. – Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male and female, Bale Mountains National Park. The female has no horns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Running female, Bale Mountains National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tragelaphus scriptus Bushbuck

This antelope is very widespread, found in all of sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of the Congo Rainforest Basin and the arid areas of Somalia, Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa. It lives in various types of forest and in savanna woodland.

The specific name is derived from the Latin scribe (“I write”), referring to the script-like spots that are often present along the flanks of the animal. The pale spots and lines in the coat are an adaptation. This species is often feeding in scrub forest, where the sunlight hits the forest floor as spots and lines.

Some scientists split this species into between 2 and 8 separate species.

The coat of adult bushbuck males may be almost black. – Lake Nakuru, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female bushbuck, feeding in dry shrub forest, Victoria Falls National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a female, Victoria Falls National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tragelaphus spekii Sitatunga

The very long hooves of this antelope can be widely splayed, an adaptation to run in wet or swampy areas without sinking in. It is an excellent swimmer and may dive when in danger, lying submerged with only the nostrils above the surface.

Three subspecies are currently recognized: the Nile, or East African, sitatunga (ssp. spekii), which lives in the Nile watershed, the Congo, or forest, sitatunga (gratus), which is distributed in western and central Africa, and the Zambezi sitatunga (selousi), found in southern Zaire, Zambia, Angola, and northern Botswana.

The rather long coat of the male of the nominate race is brown with a reddish tinge, whereas the male of the Zambezi sitatunga is slate-grey. Females are a beautiful reddish-brown. Both sexes have white markings in the face, and sometimes whitish vertical stripes on their body. Only the male has horns, which are rather short and slightly spiralled.

The specific name was given in honour of English officer and explorer John Hanning Speke (1827-1864), who explored eastern Africa on three expeditions. He attempted to find the source of the Nile, and was the first European to reach Lake Victoria.

Male Nile sitatunga, ssp. spekii, Saiwa Swamps National Park, western Kenya. In the upper picture, a grey heron (Ardea cinerea) is also seen. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male Zambezi sitatunga, ssp. selousi, Kasanka National Park, northern Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Aepycerotinae, genus Aepyceros

Aepyceros melampus Impala

This rather large, but slender and graceful antelope constitutes the sole member of this subfamily. The male is a magnificent animal, with lyre-shaped horns, which may reach a length of 90 cm.

This species is common in much of eastern and southern Africa. Two subspecies are recognized, the nominate, which is distributed from southern Uganda and central Kenya southwards to eastern South Africa and the major part of Namibia, and subspecies petersi, known as black-faced impala, which is restricted to north-western Namibia and south-western Angola. This subspecies can be identified by the black markings on its face.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek aipus (‘high’ or ‘steep’) and keras (‘horn’), referring to the long horns of the male, whereas the specific name is from the Greek melas (‘black’) and pous (‘foot’), alluding to the black spots on its hind feet. The name impala is a corruption of the Tswana word phala, which means ‘red antelope’.

Herd of impalas, illuminated by morning sun, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Impalas, drinking from a waterhole, Chief’s Island, Okawango Delta, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male impalas are magnificent animals, as is obvious in these pictures from Samburu National Park, Kenya (top), and Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sparring males, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is chasing a female, sniffing her vagina to test whether she is in heat, and then mounts her. – Serengeti National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male black-faced impala, subspecies petersi, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This cave painting near Ngomakirira, Zimbabwe, which was made by San people (‘Bushmen’), depicts hunters, pursuing an impala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Nesotraginae, genus Nesotragus

This subfamily contains only two species, the suni (below) and Bates’s dwarf antelope (N. batesi). They were formerly erroneously included in the tribe Neotragini (dwarf antelopes). However, genetic research has revealed that their nearest relative is the impala (above).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek nesos (‘island’) and tragos (‘billy-goat’), perhaps referring to the habitat of these animals being dense forests.

Nesotragus moschatus Suni

This tiny antelope, only 30-43 cm high at the shoulder and weighing 4-5 kilos, lives in dense thickets in a belt along the African East Coast, from central Kenya southwards to north-eastern South Africa. Four subspecies are accepted.

Populations have been much reduced by poaching, habitat loss, and predation by dogs, especially in South Africa, where it is confined mainly to north-eastern KwaZulu-Natal.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘smelling of musk’.

This suni has been trapped illegally by poachers in a snare, Rondo Forest Reserve, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Oreotraginae, genus Oreotragus

Oreotragus oreotragus Klipspringer

In former days, this small antelope was included in the tribe Neotragini. However, genetic research has shown that its nearest relative is the suni (above), but it differs sufficeiently to form its own subfamily.

The outer keratin layer on its hooves is rubber-like, causing them to have a tremendously firm grip on steep surfaces – an adaptation to its rocky habitat. It prefers rocks with scattered bushes, where it can seek shelter from enemies, including eagles.

It is widely distributed, mainly in eastern and southern Africa, from eastern Sudan and Eritrea southwards through East Africa to north-eastern South Africa, and also in western Angola, Namibia, and western South Africa. Small remnant populations exist in western Central African Republic and in Nigeria. It has been observed as high as 4,500 m altitude on Mount Kilimanjaro. About 11 subspecies have been described.

The klipspringer is an animal of rocky habitats. These pictures show Cape klipspringer, subspecies oreotragus, Augrabies National Park, South Africa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male (left) and female, Augrabies National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting male, Augrabies National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male Masai klipspringer, subspecies schillingsi, resting on a rocky outcrop, a so-called kopje, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae

This subfamily consists of 3 tribes.

The tribe Antilopini contains the blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra, below), African and Asian gazelles of the genera Procapra, Gazella, Eudorcas, and Nanger (the latter 3 presented below), the springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis, below), the dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei), and the gerenuk (Litocranius walleri, below).

The tribe Saigini contains a single species, the Asian saiga (Saiga tatarica).

The tribe Neotragini contains the beira (Dorcatragus megalotis), the genus Madoqua (below), which has 4 species, the royal antelope (Neotragus pygmaeus), the oribi (Ourebia ourebi), and the genus Raphicerus (below).

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Antidorcas

This tribe contains a single species, distributed in southern Africa.

Antidorcas marsupialis Springbok

When the Boer (Dutch immigrants) arrived in South Africa in the 18th Century, they noticed a species of antelope, which would often jump about, obviously for sheer pleasure. For this reason, they named it springbok (’jumping buck’). This behaviour is called pronking, where an animal, on stiff legs, leaps several times into the air, sometimes as much as 2 m above the ground, arching its back and raising a pocket-like, white skin flap, which extends from the tail along the midline of the back.

The scientific name is derived from Ancient Greek anti (‘opposite’) and dorkas (‘gazelle’), indicating that this animal is not a true gazelle, and from the Latin marsupium (‘pocket’), alluding to the skin flap on the back. Another difference from the gazelles is that its horns are either straight, or with the tips curving slightly forward, whereas those of the gazelles usually curve backward in an arch. (However, see Grant’s gazelle below.)

The springbok lives in dry areas of south-western Africa, from extreme southern Angola southwards through Namibia and western Botswana to western South Africa. It is the national animal of South Africa.

Springbuck in their typical habitat, desert with scattered trees, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When the Boer arrived in South Africa, they noticed a species of antelope, which would often jump about, obviously for sheer pleasure. These springbuck are jumping across a stream in Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a springbok, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Springbok horns are either straight, or with the tips curving slightly forward. – Kalahari Gemsbok National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is about to quench his thirst at a waterhole in Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, together with numerous ring-necked doves (Streptopelia capicola). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Springbok, eating a tsamma melon (Citrullus lanatus), Kalahari Gemsbok National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Springbok, scratching its head, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Springbok kids seem to consist of only thin legs. – Kalahari Gemsbok National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana), which was drinking from a stream in Etosha National Park, seems to be annoyed by the presence of a springbok. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Antilope

This tribe contains a single species, found in India.

Antilope cervicapra Blackbuck

The male of this species is a wonderful creature: coal black, with white markings on face, legs and belly, and long, straight, spiralled horns, growing to 65 cm long in some individuals. During territorial battles, the males spar with their horns, trying to gather as many females as possible for their harem. Females and young males have more subtle colours, being brown and white.

Formerly, this gorgeous animal was distributed all over plains and semi-deserts in India and Pakistan, but uncontrolled hunting by British and Indian ‘sportsmen’ (as they were fond of calling themselves), and competition from grazing cattle, goats and sheep, took their toll.

The blackbuck disappeared completely from Pakistan, and from most of India. Larger herds survived only in the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat, mainly because the animals were protected by the Bishnoi and other local peoples. Traditionally, they protect all wild animals, even allowing them to graze in their fields of wheat and lentils. Thanks to their protection of the blackbuck, biologists have been able to re-introduce the species to many locations in India.

The blackbuck also plays a role in Hindu mythology, where the chariot of the moon god Chandrama is pulled by this animal.

The specific name is derived from the Latin cervus (‘deer’) and capra (‘she-goat’), thus ‘deer-goat’.

At the outskirts of the town of Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu, a huge sculpture, measuring c. 15 by 30 m, has been carved into two boulders. The main theme of this sculpture, which has been dubbed The Descent of the Ganges, is an event in the Hindu epic Mahabharatha. Bhagiratha was a great king, doing penance for a thousand years to obtain the release of his 60,000 great-uncles from the curse of Saint Kapila, eventually leading to the descent of the goddess Ganga to Earth, in the form of River Ganges. However, many other themes have been included in the sculpture, including animals like elephants, cats, and blackbuck.

My difficulties to obtain permission to photograph blackbuck in Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary are related on the page Travel episodes – India 1979: Hunting blackbuck with camera.

Adult male blackbuck, Gudi, near Osiyan, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sub-adult males with brownish parts, Gudi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Females and sub-adult males, Gudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Adult male, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An adult male shows a threatening attitude towards another male, which runs away, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Younger males, Tal Chapar Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blackbuck, Velavadar National Park, Gujarat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blackbuck at a waterhole, Velavadar National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Detail of the sculpture ‘The Descent of the Ganges’ (see text above), depicting blackbuck. – Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Eudorcas

Members of this African genus, often called ring-horned gazelles, were once included in the genus Gazella, subgenus Eudorcas, which has since been elevated to a separate genus with 4 or 5 species, of which one, the North African red gazelle (E. rufina), is extinct. The status of the Mongalla gazelle (E. albonotata), which lives in South Sudan, is disputed. Some consider it a separate species, some claim that it is a subspecies of Thomson’s gazelle (below), and others regard it as a subspecies of the red-fronted gazelle (E. rufifrons).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eu (‘good’) and dorcas (‘gazelle’).

Eudorcas thomsonii Thomson’s gazelle

This small species is probably the most common of the gazelles, with a population of around 500,000. It is distributed from central Kenya southwards to central Tanzania. Two subspecies have been described, thomsonii, which is found east of the Rift Valley, and nasalis, which lives west of the Rift Valley.

Despite being among the fastest mammals on the planet, which is able to run at almost 90 km/h over short distances, it is a favourite prey of the African hunting dog (Lycaon pictus). One such hunt is described on the page Animals: Hunting dogs – nomads of the savanna.

Thomson’s gazelle was described by German-born British naturalist Albert Günther (1830-1914), who named it Gazella thomsoni, honouring Scottish geologist Joseph Thomson (1858-1895) – an excellent explorer, who never caused the killing of any native, or lost any of his men due to confrontations. His motto was “He who goes gently, goes safely; he who goes safely, goes far.”

Thomson’s gazelle is a very handsome animal, brown and white, with a prominent black stripe along the flanks. These pictures show a male Serengeti Thomson’s gazelle, subspecies nasalis, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male, chewing the cud, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sparring males, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over shorter distances, Thomson’s gazelle can run at almost 90 km/h. – Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Gazella

This genus was erected in 1758 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who named it for the Arabian word for gazelle, gazal. It is found in the northern half of Africa, Arabia, the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Indian Peninsula. It includes 10 species, of which 3 have gone extinct.

Formerly, the genus was larger, but 4 or 5 species have been transferred to the genus Eudorcas (above), 3 to Nanger (below).

My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag.

Behold, there he is standing behind our wall,

Gazing through the windows,

Looking through the lattice.

Until the cool of the day,

When the shadows flee away,

Turn, my beloved, and be like a gazelle,

Or a young stag on the mountains of Bether.

Song of Solomon, 2:9, 2:17.

Gazella bennettii Chinkara, Indian gazelle

This small species is distributed from central and eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan eastwards through southern Pakistan to southern central India, living in deserts, arid hills, and dry scrub forests. In Pakistan, it has been found up to elevations of 1,500 m.

Six subspecies are recognized, some of which are regarded as full species by some authorities: The Deccan chinkara, subspecies bennettii, is distributed from the Gangetic Plain southwards to Andhra Pradesh, the Gujarat chinkara, ssp. christii, from southern Pakistan eastwards to Rajasthan and Gujarat, the Salt Range gazelle, ssp. salinarum, in eastern Pakistan and north-western India, the Kennion or Baluchistan gazelle, ssp. fuscifrons, in eastern Iran, southern Afghanistan, southern Pakistan, and Rajasthan, the Jebeer gazelle, ssp. shikari, in north-eastern Iran, and the Bushehr gazelle, ssp. karamii, in a small area near Bushehr, north-eastern Iran.

Populations of this gazelle have been severely reduced by hunting. The Iranian and Pakistani populations are scattered and fragmented, and it may be extinct in Afghanistan. The stronghold of the species is India, with an estimated 100,000 individuals, of which about 80,000 live in the Thar Desert in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

The specific name may refer to English physician and naturalist George Bennett (1804-1893), who travelled widely between 1828 and 1835. Later, he emigrated to Australia, where he held a number of posts, including president of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Gujarat chinkaras, subspecies christii, in morning light, near Osiyan, Thar Desert, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Detail of the sculpture ‘The Descent of the Ganges’ (see blackbuck above), depicting chinkaras. – Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gazella dorcas Dorcas gazelle

The dorcas gazelle was described in 1758 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who named it for the Arabian word for gazelle, gazal, and the Greek word for these animals, dorkas. This species lives in arid grasslands of deserts and semideserts in northern Africa, from Morocco and Mauritania eastwards to Egypt and the Sudan, and along the Red Sea coast southwards to Somalia. It is also found in Israel.

Six subspecies are recognized: dorcas (Egyptian dorcas gazelle), isabella (isabelline dorcas gazelle), massaesyla (Moroccan dorcas gazelle), osiris, incl. neglecta (Saharan dorcas gazelle), beccarii (Eritrean dorcas gazelle), and pelzelnii (Pelzeln’s gazelle or Somali dorcas gazelle).

Relief in the Hakim Mosque, Old Cairo, Egypt, depicting an Egyptian dorcas gazelle. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Litocranius

Litocranius walleri Gerenuk

This slender, long-necked antelope, also known as giraffe gazelle, lives in arid areas, from south-eastern Ethiopia and Somalia southwards through eastern Kenya to north-eastern Tanzania. The males, which may weigh up to 52 kg, have horns that are lyre-shaped, measuring up to c. 45 cm long, whereas the females are hornless.

This species was described in 1878 by Anglo-Irish naturalist Sir Victor Alexander Brooke (1843-1891). The generic name is from the Greek lithos (‘stone’) and the Latin cranium (‘skull’). Apparently, the gerenuk has a hard skull. The specific name was given in honour of English naturalist Richard Waller (c. 1655-1715), whereas the common name derives from a Somali word, garanuug, meaning ‘giraffe-necked’.

Two subspecies are identified, northern gerenuk or Sclater’s gazelle, ssp. sclateri, which is found from eastern Ethiopia and Djibouti southwards to north-western Somalia, and southern gerenuk or Waller’s gazelle, ssp. walleri, which is distributed from central Somalia southwards to north-eastern Tanzania. Sclater’s gazelle was named for English lawyer and zoologist Philip Lutley Sclater (1829-1913).

Southern gerenuk, subspecies walleri, feeding on acacia leaves, Samburu National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Antilopini, genus Nanger

Like members of the genus Eudorcas (above), members of the genus Nanger, comprising 3 African species, were once included in the genus Gazella, but have since been moved to a separate genus.

The generic name is a local Senegalese name for the dama gazelle (Gazella dama).

Nanger granti Grant’s gazelle

This powerful gazelle was named for Scottish explorer Lieutenant-Colonel James Augustus Grant (1827-1892), who explored parts of East Africa. Five subspecies have been described, distributed from South Sudan and Ethiopia southwards through Kenya to northern Tanzania.

The male has thick horns that curve backwards and outwards, whereas the female has slender, usually straight horns, with the tip pointing slightly forward. In this respect, they resemble those of the springbok (above).

Circling around each other, these Grant’s gazelle males are performing dominance display, showing their opponents the size of their body and horns. In this way, one may withdraw, thus avoiding to fight against a stronger opponent. – Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grant’s gazelle females have slender, usually straight horns, with the tip pointing slightly forward. – Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suckling kid, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nanger soemmerringii Sömmerring’s gazelle

This large gazelle, also known as Abyssinian mohr, was described by German physicist and naturalist Philipp Jakob Cretzschmar (1786-1845) and named in honour of another German physicist and naturalist, Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring (1755-1830).

Three subspecies are recognized, native to eastern Africa, from Eritrea and South Sudan through Ethiopia to Somalia. It is extinct in Sudan, and is also threatened in its present area of distribution.

Male Sömmerring’s gazelle, Awash National Park, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Neotragini, genus Madoqua

Dik-diks are 4 species of tiny African antelopes, standing between 30 and 45 cm tall and weighing no more than 3 to 7 kg. They are named for the alarm calls of the females, a trumpet-like zik-zik. Males mark their territory with secretions from an eye gland (see photo at the beginning of this page).

The generic name is a local Amharic word, medaqqwa, used for these small antelopes.

Madoqua guentheri Günther’s dik-dik

This small species is found in arid areas of southern Ethiopia and South Sudan, eastern Uganda, northern Kenya, and Somalia.

It was named in honour of German-born British zoologist Albert Günther (1830-1914), whose specialties were fishes and reptiles. He described more than 340 reptile species and was the first to conclude that the tuatara of New Zealand is not a lizard, but the only living member of an entirely new group of reptiles, which he named Rhynchocephalia.

Günther’s dik-dik, Lake Baringo, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Madoqua kirkii Kirk’s dik-dik

Four subspecies are distributed from extreme eastern Uganda, northern Kenya, and southern Somalia southwards to southern Tanzania, whereas a fifth, ssp. damarensis, which forms a disjunct population in western Angola and north-western Namibia, may constitute a separate species.

British physician, naturalist, and Governor General of Zanzibar, Sir John Kirk (1832-1922), collected many plants and animals in eastern Africa and published numerous papers. Many species are named after him, including this antelope. He was also the leading figure in ending the slave trade in Zanzibar, with the aid of his political assistant, Ali bin Saleh bin Nasser Al-Shaibani.

Male Kirk’s dik-dik, subspecies cavendishi, standing on a termite mound, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Three Kirk’s dik-dik, subspecies cavendishi, perhaps male and female with a young, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Neotragini, genus Ourebia

Ourebia ourebi Oribi

This small, yellowish-brown, long-necked antelope, the only member of the genus, reaches a maximum height of 65 cm at the shoulder and weighs up to 22 kg. The male has short, straight, almost vertical horns, to 18 cm long, whereas the female has no horns. It lives singly or in family groups in grasslands and open forest, up to elevations around 2,000 m.

Eight subspecies have been described, found in the Sahel zone of central Africa, from Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia, and thence southwards through eastern Africa to north-eastern South Africa, and also in Angola, southern Zaire, and Zambia. It was described as early as 1782 by German zoologist Eberhard von Zimmermann (1743-1815), who wrote one of the first zoogeographical works, Specimen Zoologiae Geographicae Quadrupedum (1777), describing the distribution of mammals.

All names of this species are a corruption of orab, the Khoikhoi name of this animal.

Male oribi, subspecies hastata, Masai Mara National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male and female hastata, Lochinwar National Park, Zambia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Antilopinae, tribe Neotragini, genus Raphicerus

This genus contains the steenbok (below) and two species of grysbok, all living in Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek raphis (‘needle’) and keras (‘horn’), alluding to the thin, straight horns of these animals.

Raphicerus campestris Steenbok

This small antelope lives in various habitats, including open woodland, savanna, and stony areas. It is distributed in two separate areas, from central Kenya southwards to southern Tanzania, and from Namibia eastwards to Zambia, and thence southwards to the Cape Region of South Africa.

It is easily identified by the enormous ears with distinct black stripes inside. The male has small, straight, pointed horns, which may be up to 19 cm long, whereas the female has no horns.

The specific name is derived from the Latin campus (‘plain’), probably in this case alluding to bush steppe. It was named steenbok by the Boer, Afrikaans for ‘stone buck’, possibly referring to the fact that some specimens are almost brick-red. This name was adopted by the English.

Steenbok males, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania (top), and Nairobi National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding female, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Reduncinae

This subfamily contains 3 genera, Kobus (below), Pelea (one species, P. capreolus, the grey rhebok), and Redunca (below). They occur in Africa south of the Sahara.

Genus Kobus

This genus is rather diverse, comprising 6 species of stocky animals, of which the waterbuck is greyish, with long pelt on the neck, whereas the other members of the genus are various shades of brown, reddish-brown, or blackish, and has short hair on the neck. Only the males have horns.

The generic name may stem from a Wolof word, koba, used for the roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus).

Kobus ellipsiprymnus Waterbuck

The greyish waterbuck is distributed across much of sub-Saharan Africa, in the Sahel zone from Senegal eastwards to southern Sudan and western Ethiopia, and thence southwards through eastern Africa to north-eastern South Africa. There are also scattered populations in Angola, Gabon, and Congo Brazzaville.

Many subspecies have been described, divided into two main groups. Members of the ellipsiprymnus group have an elliptic white marking on the rump, which gave rise to the specific name, from the Greek ellipes (‘ellipse’) and prymnos (‘rump’).

The other group is defassa, whose members have a white patch on the rump. Initially, the latter was described in 1835 by German naturalist Wilhelm Eduard Rüppell (1794-1884) as a separate species, which he named Antilope defassa, from its Amharic name.

Today, most taxonomists regard the two groups as a single species, as they interbreed, where their ranges overlap.

Subspecies, which belong to ellipsiprymnus, are found from eastern Kenya and Tanzania southwards to north-eastern South Africa, whereas defassa subspecies occupy the remaining distribution area.

Male common waterbuck of the ellipsiprymnus group, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a male of the defassa group, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male and female defassa, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male defassa, grazing in front of a huge mixed flock of great white pelicans (Pelecanus onocrotalus) and yellow-billed storks (Mycteria ibis), Lake Nakuru, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kobus kob Kob

This antelope resembles the impala (above), but is more heavily built and has black markings on the forelegs. It is found in grasslands of northern central Africa, from Senegal eastwards to southern Chad, South Sudan, Uganda, and extreme north-eastern Zaire. Three subspecies are recognized, leucotis in South Sudan, thomasi in Uganda and Zaire, and kob in the remaining area.

Uganda kob males, subspecies thomasi, Virunga National Park, Zaire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male Uganda kob, resting among tall grass, Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Younger animals, Queen Elizabeth National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Running females, Queen Elizabeth National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kobus leche Lechwe

Lechwe are stocky antelopes, standing up to 100 cm at the shoulder and weighing up to 120 kg. Three subspecies are distributed from eastern Angola and north-eastern Namibia eastwards through northern Botswana to Zambia and south-eastern Zaire. Lechwe have also been introduced to northern Australia.

These antelope live in marshy areas, feeding on aquatic plants. Their legs are covered in a water-repellant substance, which allows them to run quite fast in water, and thus having a greater chance of escaping from predators.

The red lechwe, subspecies leche, is widely distributed in wetlands of northern Botswana, north-eastern Namibia, and south-western Zambia. A core area is the Okavango Delta in Botswana.

The Kafue Flats lechwe, subspecies kafuensis, is restricted to a small area in the Kafue Flats, a seasonally inundated flood-plain on the Kafue River, south-western Zambia. It is listed on the IUCN Red List as vulnerable.

The black lechwe, subspecies smithemani, is confined to the Bangweulu Basin, northern Zambia. In former times, hundreds of thousands of these antelopes roamed the grasslands in this area, but their numbers have shrunk drastically due to uncontrolled hunting, and today there may be as few as 30,000. Only the adult male is blackish, whereas females and young are various shades of brown. Following the rainy season, when the water recedes from the flooded areas around the Bangweulu Swamps, fresh grass sprouts, and large numbers of black lechwe frequent these areas to graze.

A fourth subspecies, robertsi, called Roberts’ lechwe or Kawambwa lechwe, is now extinct. It was previously found in north-eastern Zambia.

The specific name may stem from a Sotho word, letsa, meaning ‘antelope’.

Other antelopes are also called lechwe. The Nile lechwe (Kobus megaceros) lives in swamps and grasslands in South Sudan and northern Ethiopia, and the Upemba lechwe (Kobus anselli) is restricted to the Upemba wetlands in Zaire. It was described as late as 2005.

Herd of red lechwe, grazing in a swamp on Chief’s Island, Okawango Delta, Botswana. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male red lechwe, Chief’s Island. The palms in the background are African palmyra palms (Borassus aethiopum). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male red lechwe, running full speed, Chief’s Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kafue Flats lechwe, Lochinwar National Park, Zambia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing herd of black lechwe, Kalasa Mukoso Game Management Area, Zambia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black lechwe, crossing a pond, Kalasa Mukoso. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female and kid black lechwe, running across a road, Kalasa Mukoso. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

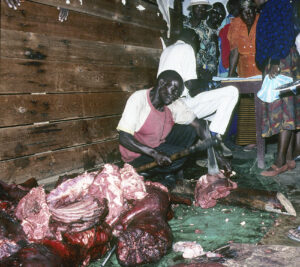

Controlled culling of the black lechwe population in the Bangweulu Swamps is taking place. In this picture, lechwe meat is sold in the town of Samfya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kobus vardonii Puku

This species has a patchy distribution, found in grasslands in Angola, northern Botswana, Zambia, eastern Zaire, and southern Tanzania. Two subspecies have been described, the nominate vardonii, found in southern parts of the distribution area, and senganus further north.

Puku, subspecies senganus, Kasanka National Park, northern Zambia. The small mounds are termite nests. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Reduncinae, genus Redunca

A genus with 3 species of reedbuck, the southern (R. arundinum), the mountain (R. fulvorufula), and the bohor (below).

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘bent backwards’, derived from uncus (‘hook’). This is odd, as the horns of these animals point forward.

Redunca redunca Bohor reedbuck

In parts of its distribution area, the bohor reedbuck is partial to moist grasslands and swamps, elsewhere it also lives in drier savannas and woodland. It is a medium-sized antelope, males measuring up to 90 cm at the shoulder, and weighing a maximum of 65 kg. Females are somewhat smaller. Only the male has horns, which may reach a length of 35 cm.

This species is distributed across the Sahel zone of central Africa, from Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia, and thence southwards to southern Tanzania. It was first described in 1767 by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811). Five subspecies are presently recognized.

Male bohor reedbuck, subspecies wardi, drinking from a stream, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. An Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus) is seen in the background. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on females of the subspecies wardi, Aberdare National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing females of subspecies wardi, Lake Nakuru, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Alcelaphinae

This subfamily contains about 6 species of rather large antelopes, including the hirola (Beatragus hunteri), the hartebeest (Alcelaphus, below), 2 species of wildebeest (Connochaetes, below), and the tsessebe, or topi, and the bontebok (both of the genus Damaliscus, below).

Genus Alcelaphus

The generic name is derived from Proto-Germanic algiz (‘moose’), and from Ancient Greek elaphos (‘deer’). This name was applied by Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811).

Alcelaphus buselaphus Hartebeest

Previously, this species was widely distributed on the entire African continent, mainly living in rather arid areas, preferably dry savannas and wooded grasslands, sometimes forming herds of up to 300 animals. The coat colour varies from pale sandy-brown to reddish or chocolate-brown, not only between the various subspecies, but also within each subspecies. Both sexes have horns, which may reach a length of up to 70 cm, shorter and more slender in females. The shape of the horns varies from lyre-shaped to almost straight, and from almost parallel to widely diverged.

The name hartebeest possibly originates from a former Afrikaans word, hertebeest, meaning deer beast. To the Boer, who named it, it seems that this antelope resembled a mixture of cow and deer. A similar case applies to the specific name buselaphus, which is derived from the Greek bous (‘cow’) and elaphos (‘deer’). This name was also given by Pallas, to whom this antelope apparently resembled a mixture of a cow, a moose, and a deer.

Eight subspecies are recognized:

The northern hartebeest, ssp. buselaphus, also called bubal, is extinct. It formerly occurred across northern Africa, from Morocco to Egypt, but was exterminated in the 1920s.

Previously, the western hartebeest, ssp. major, was distributed in much of the Sahel zone in western Africa, but today it is restricted to a few protected areas.

The Lelwel hartebeest, ssp. lelwel, was formerly found in much of the eastern Sahel zone, from southern Chad eastwards to western Ethiopia and Uganda. It has declined drastically since the 1980s and is now restricted to a few protected areas.

In former days, the Tora hartebeest, ssp. tora, occurred in north-western Ethiopia and western Eritrea. Its present status is unclear, and it may be extinct.

Today, Swayne’s hartebeest, ssp. swaynei, is restricted to a very small population in the southern Rift Valley in Ethiopia. Formerly, it was distributed eastwards to Somalia, where it was exterminated in the 1930s.

The kongoni, ssp. cokii, also called Coke’s hartebeest, is confined to southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. The population is rather stable.

Lichtenstein’s hartebeest, ssp. lichtensteinii, inhabits miombo woodland, from western and southern Tanzania southwards to Zambia, with scattered herds in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and eastern South Africa.

The red hartebeest, ssp. caama, also known as Cape hartebeest, was once distributed from southern Angola and eastern Namibia through most of Botswana to eastern South Africa. Today, it is confined to Namibia and central and south-western Botswana, but its numbers are on the rise in these countries.

The decline in most hartebeest populations is due to hunting and poaching for the legal as well as the illegal meat market, as its meat is highly praised.

Herd of kongoni, subspecies cokii, standing in front of eroded rocky outcrops, called kopjes, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kongoni males, forming symmetry, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sparring kongoni males, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Running kongoni, Hell’s Gate, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grooming kongoni, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. This animal is so reddish that it strongly resembles Swayne’s hartebeest, which, however, only lives in Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red hartebeest, subspecies caama, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Alcelaphinae, genus Connochaetes

Members of this genus, counting 2 species, are variously called wildebeest or gnu. The generic name is derived from the Greek konnos (‘beard’) and khaite (‘flowing hair’ or ‘mane’), alluding to the long, flowing beard of these animals. The name wildebeest is Afrikaans for ‘wild cow’, whereas gnu is the Khoikhoi name for these antelopes.

Connochaetes gnou Black wildebeest

The black wildebeest, also called white-tailed gnu, is endemic to the southernmost part of Africa. Wild populations were almost completely exterminated in the 19th Century due to their competition with cattle, and also the value of their hide and meat. It has now been reintroduced from captive animals in Lesotho, Swaziland, and South Africa, and also outside its natural range, in Namibia and Kenya.

Black wildebeest, Karoo National Park, South Africa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Connochaetes taurinus Blue wildebeest

This species, which is also called brindled gnu, is distributed from southern Kenya southwards through eastern Africa to central Zambia, and from southern Angola and Zambia southwards to South Africa and Mozambique. The specific name means ‘bull-like’, derived from the Greek tauros (‘bull’), whereas the prefix blue refers to the bluish sheen of the coat.

Five subspecies are recognized:

The nominate blue wildebeest, ssp. taurinus, is widely distributed in southern Africa, from southern Angola and south-western Zambia southwards to central South Africa and southern Mozambique.

Cookson’s wildebeest, ssp. cooksoni, is restricted to the Luangwa Valley, Zambia.

The black-bearded wildebeest, ssp. johnstoni, occurs from central Tanzania southwards to northern Mozambique. It is extinct in Malawi.

The eastern white-bearded wildebeest, ssp. albojubatus, lives in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, east of the Rift Valley.

The western white-bearded wildebeest, ssp. mearnsi, is found in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, west of the Rift Valley, westwards to Lake Victoria. This subspecies undertakes a spectacular annual migration, where 2 or 3 million wildebeest migrate from the Serengeti Plains northwards to southern Kenya, and later vice versa.

Blue wildebeest, subspecies taurinus, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-bearded wildebeest, subspecies johnstoni, Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Herd of western white-bearded wildebeest, subspecies mearnsi, wandering across the floor of the Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Against the light, the white beards of these wildebeest stand out clearly. In the background plains zebras (Equus quagga ssp. boehmi). – Ndutu, Serengeti National Park (top) and Ngorongoro Crater. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The coat of adult wildebeest is grey, whereas that of calves is pale brown. – Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wildebeest are often running about, obviously for sheer pleasure, frolicking, butting another member of the herd, or jumping on stiff legs. – Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When fighting, wildebeest bulls kneel down, sparring with their horns. – Ngorongoro Conservation Area. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wildebeest calves may suckle even when half-grown, in this case in the Ngorongoro Crater. The birds to the left are a blacksmith lapwing (Vanellus armatus) and a wattled starling (Creatophora cinerea). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-bearded wildebeest and plains zebras, crossing a soda lake, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-bearded wildebeests, drinking from a muddy waterhole, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During their famous annual migration, myriads of wildebeest are running down a river bank, causing huge clouds of dust to rise. – Ndutu, Serengeti National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the annual migration, wildebeest and plains zebras quench their thirst in the Grumeti River, Serengeti National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Alcelaphinae, genus Damaliscus

These large antelopes, comprising two species, live in dry savanna, semi-desert, and river valleys of sub-Saharan Africa.

The generic name is a Latin diminutive form of Ancient Greek damalis (‘a young cow’).

Damaliscus lunatus

This species, variously called topi, tsessebe, korrigum, or tiang, has a patchy distribution in the Sahel zone, and in eastern and southern Africa. These animals often stand on termite mounds for hours, surveying the surrounding territory – a typical behavior of this species.

Six subspecies have been described:

The common tsessebe, ssp. lunatus, is found from extreme southern Zaire southwards through eastern Angola and western Zambia to extreme north-eastern Namibia, northern and south-eastern Botswana, Zimbabwe, extreme north-eastern South Africa, and south-western Mozambique.

The Serengeti topi, ssp. jimela, has a patchy distribution in Uganda, southern Kenya, and Tanzania. It is common in north-western Tanzania.

The coastal topi, ssp. topi, is restricted to a coastal strip in southern Somalia and northern Kenya.

The tiang, ssp. tiang, has a patchy distribution in the eastern half of the Sahel zone.

The korrigum, ssp. korrigum, is found in two widely separated areas of the western Sahel zone.

The Bangweulu tsessebe, ssp. superstes, was described as late as 2003. It is restricted to the Bangweulu Swamps of northern Zambia.

The specific name is derived from the Latin luna (‘moon’), in this connection meaning crescent-shaped, presumably referring to the shape of the horns.

Common tsessebe, subspecies lunatus, standing sentry on a termite mound, Chief’s Island, Okawango Delta, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Males of Serengeti topi, subspecies jimela, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Damaliscus pygargus

This animal is restricted to eastern and southern South Africa. Two subspecies are recognized, the bontebok, ssp. pygargus, and the blesbok, ssp. phillipsi.

Originally, the bontebok was widespread in the Western Cape Province, but was hunted almost to extinction. By the 1930s, only 22 animals survived. Since then, it has been strictly protected in several reserves, both inside and outside its former area of distribution. Today, the population counts between 1600 and 2000 individuals.

The blesbok was distributed over a large area of eastern South Africa, but, like the bontebok, it was almost exterminated due to uncontrolled hunting. Today, it has made a remarkable recovery, and the population is estimated at 120,000.

A small herd of bontebok, subspecies pygargus, lives in Table Mountain National Park, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bontebok female and calf, Table Mountain National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male bontebok, De Hoop Nature Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Hippotraginae

This subfamily contains large African antelopes, which mainly feed on grasses. It includes 3 genera, sable and roan antelopes (Hippotragus), oryxes (Oryx), and the North African addax (Addax).

Genus Hippotragus

This genus has 3 members, the widespread sable antelope (H. niger) and roan antelope (H. equinus), and the extinct bluebuck (H. leucophaeus) of South Africa.

The generic name stems from Ancient Greek hippos (‘horse’), alluding to the large size of these animals, and tragos (‘goat’), a name attached to many antelope species.

Hippotragus niger Sable antelope

This large antelope inhabits wooded savanna, from Tanzania and extreme southern Kenya southwards to northern Botswana and north-eastern South Africa, with a separate population in central Angola. Females and juveniles are chestnut to dark brown, whereas males are much darker, black in some subspecies. Both sexes have ringed horns, arching backwards, to 1 m long in females, 1.6 m in males. Four subspecies are recognized:

The southern sable, ssp. niger, also called black sable, Matsetsi sable, or South Zambian sable, occurs south of the Zambezi River, especially in northern Botswana and Zimbabwe.

The giant sable, ssp. variani, was named due to its longer horns. It is restricted to a few locations in central Angola and is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

The Zambian sable, ssp. kirkii, also known as West Tanzanian sable, occurs north of the Zambezi River, in Zambia, Malawi, south-eastern Zaire, and south-western Tanzania. It is classified as vulnerable.

The eastern sable, ssp. roosevelti, also called Shimba sable, is the smallest of the four subspecies. It occurs in a coastal belt from south-eastern Kenya southwards through Tanzania to northern Mozambique.

Southern sable, subspecies niger, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subfamily Hippotraginae, genus Oryx

Oryx are 4 species of large antelopes, of which 3 are native to arid parts of Africa, whereas the fourth, the Arabian oryx (O. leucoryx), is restricted to the Arabian Peninsula. The Arabian oryx and the North African scimitar oryx (O. dammah) are both extinct in the wild, but have been saved from complete extinction through captive breeding. The Arabian oryx has been re-introduced to Oman and other places, whereas a semi-wild population of the scimitar oryx is found in Tunisia.

The generic name is from the Greek orygos (‘pickaxe’), referring to the pointed horns of these antelopes.

Oryx beisa Beisa oryx

This species, also called East African oryx, inhabits steppe and semi-desert from eastern Ethiopia and southern South Sudan southwards to northern Tanzania. It is probably extinct in Eritrea and Sudan. Two subspecies are recognized, the beisa oryx, ssp. beisa, which is found north of the Tana River in Kenya, and the fringe-eared oryx, ssp. callotis, which is distributed south of the Tana River.

The specific name is the Amharic name of this animal.

Beisa oryx, subspecies beisa, Meru National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Beisa oryx, Samburu National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oryx gazella Gemsbok

The gemsbok closely resembles the beisa oryx, but has an entirely black tail, a black patch at the base of the tail, and more black markings on the legs and lower flanks. It lives in deserts and semi-deserts of southern Africa, in Namibia, Botswana, extreme western Zimbabwe, and north-western South Africa.

The name gemsbok (‘chamois buck’) was applied to this species by the Boer, from the Dutch name of the European chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), alluding to the somewhat similar facial pattern of these animals.

Gemsbok, passing in front of red sand dunes, Sossusvlei, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting gemsbok, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

After drinking at a waterhole in Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, this gemsbok is blowing water through its nostrils. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, a male is attempting to mate with a female, drinking from a waterhole, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cave painting, depicting hunters pursuing gemsbok, Brandberg, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Family Antilocapridae, genus Antilocapra

Antilocapra americana Pronghorn

Another name of this animal is American antelope, which is somewhat misleading, as it is not a true antelope, but forms a separate family, Antilocapridae – a name constructed from the Greek words for antelope and goat. The name pronghorn refers to the short, straight horns, which are forked.

When the Europeans arrived in America, this species was unbelievably abundant in the West. However, uncontrolled hunting caused this iconic animal to have been almost eradicated by around 1900. Following conservation efforts in later years, it is now common again many places in the West. Today, larger or smaller herds are distributed across the western half of North America, from extreme southern Canada southwards to northern Mexico.

The pronghorn is an animal of prairies and semi-desert, here photographed near Cody, Wyoming. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A rain shower has drenched this pronghorn in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded February 2020)

(Latest update September 2024)