Animism

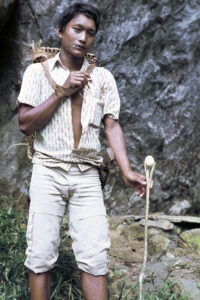

Until a few decades ago, Punan tribals of Sarawak, Borneo, were animists. This young man, photographed in 1975, presents an egg as an offering to mountain spirits. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female shaman, performing a ritual for a pilgrim (the man in yellow dress) at a Daoist temple, Siao Liouchou Island, southern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In former times, all humans were animists, who believed that everything in nature, including animals, stones, and trees, harboured a spirit, benevolent or evil, who controlled the acts of men. These spirits were able to leave the creature, or the place they dwelled, flying around to benefit or harm humans.

You had to take great care not to be possessed by an evil spirit, which could be prevented by presenting offerings, including animals, bits of cloth, or food, to the spirit. Likewise, offerings could be made to benevolent spirits to obtain their goodwill.

Still today, at several locations around the world, offerings are brought to stone cairns, sacred trees, prominent rocks, etc., indicating remnants of animism.

Carved wooden images, depicting local gods, called bulol, guard the rice harvest in an Ifugao tribal house, Bocos, northern Luzon, Philippines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sacred stones have been placed on this scaffold in the Punan village of Long Ba, Sarawak, Borneo. In the old days, pig blood was smeared onto these stones before the men went head-hunting. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The picture below was taken in a village, inhabited by Jani tribals, near Kotpad, Odisha (Orissa), eastern India. It shows clay images, which have been placed as offerings beneath a sacred tree outside a shrine, dedicated to a local goddess, Mauli. I was told that an offering of a clay tiger, for instance, would protect you against tigers, an offering of a clay cow would protect against disease among cattle, etc.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Before the introduction of Hinduism and Buddhism, many Asian animists practiced a religion called Bon (pronounced with a long ‘o’). For some of these animists, the ox was a sacred animal, which was revered, and oxen were often presented as offerings to gods or spirits.

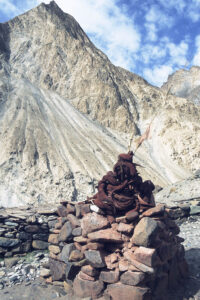

Today, traces of this ancient practice may still be seen, especially in Ladakh, northern India, where horns of cows, yaks, and wild goats are placed as offerings on stone cairns. The horns and stones are often painted red, in which case they are called Lato Marpo (‘Red Gods’). The red dye probably symbolizes blood from sacrificed animals.

Horns of yak and Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica), painted red, have been placed as offerings on cairns, Markha Valley, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the kora (pilgrim route) around Tashilhunpo Monastery, Shigatse, Tibet, a yak skull has been placed as an offering near mani stones, slabs with carved Buddhist mantras. Note that mantras have also been carved into the skull. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This skull of a bharal, or Himalayan blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur), has been placed among Tibetan prayer flags and fragrant juniper branches (Juniperus), Kagbeni, Mustang, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This offering had been placed along a trail near Kakani, Helambu, Nepal. It consists of eggs and small figures (gods?), made from sticky rice and soil (?), with hats made from banana leaves. It clearly shows traces from pre-Hindu and pre-Buddhist animism. A few seconds after the upper picture was taken, a dog ate the whole thing. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture possibly shows a local animist deity, carved in stone, which has been erected outside a gompa (a Tibetan Buddhist monastery) near the village of Nagonde, Helambu, central Nepal. Poles with Buddhist prayer flags are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A little herder in Tashigaon, Arun Valley, eastern Nepal. He is wearing a necklace with corals and turquoise, and a talisman bag, the latter probably a remnant from animism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Hindu in the picture below has placed a flower offering, consisting of yellow Primula stuartii, yellow Geum elatum, and blue and white Anemone obtusiloba, on a stone cairn, dedicated to a local goddess, atop the peak Rakhundi (3622 m), Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh, India. This goddess is probably a form of Devi, the god Shiva’s shakti (female aspect), as the trident is a symbol of Shiva.

The mentioned plants are all described on the page Plants: Himalayan flora.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I found this offering, consisting of small clay figures and sticks with bits of paper attached, on a mountain trail in the Modi Khola Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A little doll, placed on a tiny wagon, Honnavar Forest, Karnataka, South India. Black magic? Or perhaps an offering to ask the gods to cure a disease? (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sacred village trees and groves

When primitive Man began to control fire, life-giving warmth was obtained by burning wood during cold nights. On hot days, trees would provide cooling shade. Some trees would yield an abundance of fruits or other food, and a decoction of bark or leaves from certain trees would cure or ease a number of diseases. Much later, trees provided timber for houses, tools, wagons, ships, etc. A steady flow of gifts for humanity.

In the vast forests, certain trees, especially hollow ones, supposedly possessed enormous powers, and for the hunter it was wise to be on good terms with the tree women. He would bring offerings to them, having a mysterious mythical-erotic relationship with them.

When humans began building villages, a tree would often be planted on the founder’s grave, around which the village was centered. This sacred tree, which was believed to be endowed with the spirits of the deceased village members, could be birch (Betula), oak (Quercus), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), linden (Tilia), Norway spruce (Picea abies), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), or yew (Taxus baccata). During festivals, mead was presented as an offering, and also blood, when animals were slaughtered.

Until about a hundred years ago, among certain African tribes in Liberia, a tree would be planted, when a village was founded, and a beautiful maiden would be buried alive under the tree. By this act, the tree would be endowed with the spirits of the forefathers. The surroundings of the tree were protected, and if weaver birds (which are usually regarded as serious pests, because they eat crops), founded a colony in the tree, nobody dared to harm them. If they were pursued, the village had to be burned down, and a new one established far away.

When the various religions arose, it was only natural that parts of the old animism would be incorporated in the new beliefs. Sanctity of trees has lingered up to the present day. Many cultures and religions still have sacred groves, often situated around temples or graveyards. The trees in these groves are believed to contain supernatural powers, and they are never cut down, even during periods of starvation.

To our ancient forefathers, hollow trees possessed enormous powers. This picture shows one such tree, Ulvedalsegen (’Wolf Valley Oak’), north of Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This grove of old drooping junipers (Juniperus recurva), near the Pangboche Monastery, Khumbu, eastern Nepal, is sacred to the local Tibetan Buddhists – a remnant of animism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The conifers in the pictures below, photographed in the Tirthan Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India, are the abode of Koru, a local Hindu goddess, and the trunks have been adorned with offerings, including pieces of cloth, kerosine lamps, padlocks, and chains. This habit is probably a remnant of pre-Hindu animism. The small tridents, called trisul, indicate that Koru is a form of Devi, the god Shiva’s shakti (female energy), as the trident is a symbol of Shiva.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This large Indian holly oak (Quercus floribunda), growing near Dharkot, Uttarakhand, India, serves as a ‘money tree’. To obtain good luck, coins are hammered into the bark as offerings. This custom may be a remnant of pre-Hindu animism. Rhododendron flowers have also been brought as an offering at the foot of the tree. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tree worship in Norse religion

In Norse mythology, which evolved during the late part of the Iron Age, the sacred village tree was mythologically enlarged to a tree of gigantic dimensions, called Yggdrasil. The branches of this tree stretched across the entire world, housing gods, giants, and people.

Traditionally, Yggdrasil is considered to be an ash (Fraxinus excelsior), but many scholars now believe that it was a yew (Taxus baccata), as the sacred tree in the shrine of Uppsala, Sweden, according to several sources, was an evergreen.

The Norsemen had sacred groves, in which sacrifices were presented to Odin (Wodin), the Sky God. Around 1070, historian Adam of Bremen describes one such shrine in Uppsala: “Of every kind of living beings, nine males are sacrificed, their blood believed to reconcile the gods. The bodies themselves are strung up in the trees of a grove next to the shrine. This grove is so sacred to the heathens that each and every tree in it is considered to be divine through the death and decay of the victims. Here are the corpses of dogs and horses, and also of humans, and a Christian has told me that he observed 72 such corpses, hanging close to one another.”

Other names of Odin was ’God of the Hanged’ or ’Lord of the Gallows’, and also Yggr (‘The Terrible One’). Yggdrasil is sometimes translated as ’Odin’s Steed’, and according to Hávamál (’Words of the High One’, from the Old Norse Edda), Odin hung nine days in Yggdrasil, sacrificed by himself to himself, in his eternal quest for knowledge. (Nine was a sacred number to the Norsemen.)

In the Nordic countries, far into the 1800s, the so-called eye trees supposedly possessed supernatural healing powers. On such trees, two branches had joined to form a circular or oval opening, through which sick persons, notably children with rickets, were pushed, naked. This ceremony had to be performed at night, and, preferably, on a Thursday night – presumably a remnant of the Norse religion, as Thursday means ‘Day of Thor’. By undergoing this ritual, the sick one would be reborn, healed.

Many scholars believe that Yggdrasil was a yew. This picture shows an ancient yew in Gleann Dá Loch (Glendalough), Ireland. To the right, still clinging to the trunk, is a withered ivy (Hedera helix). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Formerly, this old common oak (Quercus robur), growing in Leestrup Forest, Zealand, Denmark, was an eye tree. However, during a storm in 1967, the branch, which formed the ‘eye’, broke off, leaving only a small stump. This man is lifting his little daughter over the stump, for fun. The oak has been dubbed Kludeegen (‘Rag Oak’). In the old days, people attached bits of cloth to the tree as an offering, and this ancient habit has been adopted by tourists today. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This is another eye tree, named Pramdrageregen (‘Barge-haulers’ oak’), which is situated near the Gudenå River, Jutland, Denmark, where, in former times, men would haul barges up or down the river, using long ropes, which were attached to the barge from the bank. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shamanism

Animism is often connected with shamanism, which is healing by exorcism of evil spirits. Even today, this healing practice takes place among tribes, which have not yet become completely ‘civilized’.

This ancient tribal cave painting in Painted Cave, Niah National Park, Sarawak, Borneo, depicts a shaman in a boat. The spiral indicates that the artist was in a hallucinogenic trance, when he made the painting. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This petroglyph on a rock in Capitol Reef National Monument, Utah, United States, probably depicts shamans, wearing masks during a ceremony. The horn-like decorations on the masks could represent horns of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), which are also depicted on the wall. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

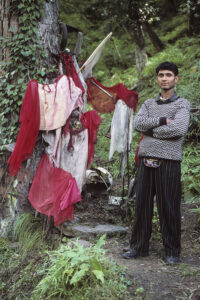

This female Jani tribal shaman, living in a village near Kotpad, Odisha (Orissa), eastern India, is standing next to a sacred pole outside a shrine, dedicated to a local goddess, Mauli. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

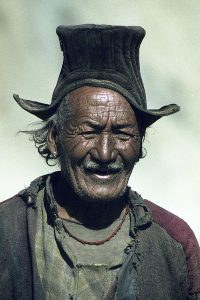

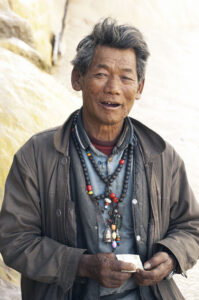

This shaman from the Markha Valley, Ladakh, India, wears the typical high felt hat of the area, and a rosary with 108 beads, made from plant seeds. (108 is a sacred number to Buddhists.) Officially, Ladakhi shamans are Buddhists, but their practice contains many traces from Bon, the pre-Buddhist religion of Central Asia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

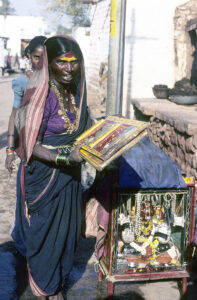

This tribal woman in the city of Badami, Karnataka, India, is probably a shaman. She is collecting money to be presented to a local goddess. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Performance for tourists in Kathmandu, Nepal, depicting a shamanistic healing dance among Jhankri tribals. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

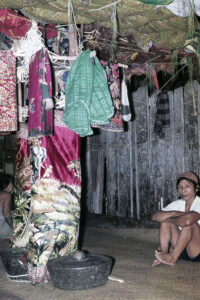

In 1975, during a stay in Long Ba, a Punan tribal village in Sarawak, Borneo, I witnessed a ceremony, in which a shaman tried to heal a sick person in a healing room in the longhouse. A scaffold, with a burning candle atop, was decorated with brightly coloured bits of cloth.

In the evening, the shaman, the sick man, and several older women circumambulated the scaffold, while three girls beat drums of various size. The shaman, wearing a special headgear with numerous hornbill feathers attached, then performed a dance to urge the evil spirit to leave the sick man’s body.

The sick Punan man, sitting in the healing room. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In 1984, I participated in another healing ceremony in the Ifugao village of Bocos, northern Luzon, Philippines, described in detail on the page Travel episodes – Philippines 1984: Shamanism among Ifugao tribals.

During the healing ceremony, an Ifugao shaman thrusted a sharpened bamboo stick deep into the lungs of a pig, twisting it several times. The pig screamed horribly for a couple of minutes, and then died of suffocation. Its screams were a signal to the evil spirit that the offering was meant for him, and he would leave the body of the sick person.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The prevalent religion in Taiwan, and in certain parts of China, is a unique mixture of Daoism and Buddhism, containing many traces from pre-Buddhist animism. Tibetan Buddhism, too, has many traces from the pre-Buddhist religion Bon.

Female shaman, performing a ritual for a pilgrim (the man in yellow dress) at a Daoist temple, Siao Liouchou Island, southern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The upper picture below shows an animistic shrine, a crack in deposited calcium bicarbonate terraces at Baishueitai, Yunnan Province, China. This crack resembles a vagina, and a lump above it symbolizes the pubic hairs. Incense sticks have been stuck into a tuft of grass beneath the crack.

At the shrine, we encountered a dongba (shaman) of the local Nakhi people. In the bottom picture, he places juniper foliage on the head of a pilgrim. Incidentally, juniper foliage is widely used as incense in Asia.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vision quests on Bear Butte

Bear Butte is an ancient volcano in South Dakota, United States, which is sacred to the local Lakota people. My late friend John Burke and I climbed this mountain in 1999. On our way up the steep trail, we noticed several spots, which had been decorated with small bits of brightly coloured cloth, or by small medicine bags.

John, who was convinced that magnetic anomalies in the ground were mind-altering, at once began measuring the magnetic field at these spots, and he measured a magnetic anomaly at every single one of them. The shaman, who had decorated these sites, had been able to detect them by sheer physical sensitivity.

The top of Bear Butte is flat, but only about 100 m long and 10 m wide. Where the trail ended, two dead trees, lavishly festooned, were framing a stunning panorama of the plains to the north, at the edge of a 300-metre vertical cliff. At this spot, John measured the most powerful magnetic anomaly he had ever encountered.

At various locations on the top, he found five magnetic anomalies, four of which had been marked by a ring of stones around the spot. The fifth, which had the strongest anomaly, was marked in an entirely different way, with a complex set of colored flags that marked out four corners, with strings of knotted cloth connecting them, while tiny ‘flagpoles’ and Y-shaped vertical sticks held a horizontal stick. The poles and sticks were from willow, which does not grow on top of the butte.

Later, in the nearby Crazy Horse Monument book store, we found a book, in which it was described how a Lakota man had asked for and was granted a night vision quest. He was brought to the top of a butte and lead to a spot, which was similar to the one we had seen on Bear Butte, complete with colored flags at each compass point, strings, and willow sticks and poles. In the hours around dawn (when telluric currents there would have been strongest), the man reported extremely dramatic visions and came down the mountain, forever cured of his alcoholism, which was the cause of requesting the vision quest.

Vision quests, and many other subjects connected with magnetic anomalies and telluric ground currents, are described in detail elsewhere on this website, on the page Book: Seed of Knowledge, Stone of Plenty: Understanding the Lost Technology of the Ancient Megalith-Builders. Other aspects of John’s extensive work are also described, whereas his interesting and multifarious life is related on the page People: John Andrew Burke (1951-2010).

John Burke, standing at two dead, festooned trees with the densest cloth cluster of all on Bear Butte. Right here was the most powerful magnetic anomaly he had ever measured. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Atop Bear Butte, a spot had been marked with small piles of rocks holding two-foot willow ‘flagpoles’ that marked the cardinal directions. Connecting the four flags were strings covered with hundreds of knotted bits of brightly colored cloth. Such spots are Native American sites for vision quests. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This small medicine bag had been tied to a tree to indicate a vision quest spot. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

References (all in Danish)

Bæksted, A. 1974. Guder og helte i Norden. Politikens Forlag.

Fritzbøger, B. 1994. Kulturskoven. Dansk skovbrug fra oldtid til nutid. Gyldendal.

Hansen, M.A. 1952. Orm og Tyr. Wivels Forlag.

Marc, F. 1968. De frie slavers land. Aschehougs Minervabøger.

Nielsen, H. 1976. Lægeplanter og trolddomsurter. 3. udg. Politikens Forlag.

(Uploaded April 2016)

(Latest update November 2021)