Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

The spotted killer

The leopard eats a wide variety of prey, including larger animals like various species of deer and antelope, wild boar (Sus scrofa), and warthog (Phacochoerus africanus). Leopards are excellent climbers, and larger prey is usually dragged up into a tree, where they can enjoy their meal in peace, out of reach of lions (Panthera leo) and spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). If the prey is too large to be dragged up a tree, these animals will often chase away the leopard and eat its prey.

Because of the leopard’s habit of storing larger prey in trees, these kills are often observed, and thus one tends to get a biased view of its diet. In reality, smaller prey like hares, dik-dik antelope, hyraxes, and various birds, including guineafowl and francolins, constitute the main diet of the leopard (Hamilton 1976, Moss 1982). Also other members of the cat family, including serval (Leptailurus serval) and wild cat (Felis silvestris), are occasionally killed and eaten.

I even once saw a leopard in Tanzania, feeding on a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), a cat which is almost as big as itself. A cheetah can easily outrun a leopard, so either this particular cheetah was wounded, or the leopard surprised it by jumping on it from a tree.

Near villages, leopards often kill cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs.

While she is away hunting, a mother leopard will hide her kittens in a patch of dense grass or another safe place, to avoid them being eaten by predators. As soon as the kittens are large enough to climb, they take shelter in a tree, where they are safe from most predators.

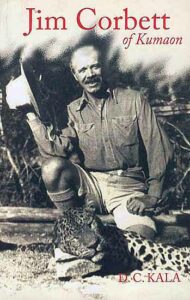

In his book The Man-eating Leopard of Rudraprayag, the famous hunter, writer, and conservationist Jim Corbett (1875-1955) relates his hair-raising adventures, when he, between 1918 and 1926, was trying to rid the people of Garhwal, Uttarakhand, of the infamous man-eating leopard of Rudraprayag, a terrible animal, which killed 125 people, before Corbett managed to shoot it.

The following extract from his book gives a vivid picture of the terror, caused by this leopard among the hill people:

The pilgrims were unwilling to accept this advice; they said they had done a long march that day and were too tired to walk another four miles, and that all they wanted were facilities to prepare and cook their evening meal, and permission to sleep on the platform adjoining the shop. To this proposal, the shopkeeper vigorously objected. He told the pilgrims that his house was frequently visited by the man-eater, and that to sleep out in the open would be to court death.

While the argument was at its height, a sadhu [holy man] on his way from Mathura to Badrinath arrived on the scene and championed the cause of the pilgrims. He said that if the shopkeeper would give shelter to the women of the party he would sleep on the platform with the men, and if any leopard – man-eater or otherwise – dared to molest them he would take it by the mouth and tear it in half.

To this proposal, the shopkeeper had perforce to agree. So, while the ten women of the party took shelter in the one-roomed shop behind a locked door, the ten men lay down in a row on the platform, with the sadhu in the middle.

When the pilgrims on the platform awoke in the morning, they found the sadhu missing, the blanket on which he had slept rumpled, and the sheet he had used to cover himself with partly dragged off the platform and spotted with blood. At the sound of the men’s excited chattering the shopkeeper opened the door, and at a glance saw what had happened. When the sun had risen, the shopkeeper, accompanied by the men, followed the blood trail down the hill and across three terraced fields, to a low boundary wall; here, lying across the wall, with the lower portion of his body eaten away, they found the sadhu.”

Fifty yards from the tree, while climbing over a rock, Ibbotson slipped, the base of the lamp came in violent contact with the rock, and the mantle fell in dust to the bottom of the lamp. The streak of blue flame directed from the nozzle on to the petrol reservoir gave sufficient light for us to see where to put our feet, but the question was how long we should have even this much light. Ibbotson was of the opinion that he could carry the lamp for three minutes before it burst. Three minutes, in which to do a stiff climb of half a mile, over ground on which it was necessary to change direction every few steps to avoid huge rocks and thorn bushes, and possibly followed – and actually followed as we found out later – by a man-eater, was a terrifying prospect.

(…) When we eventually reached the footpath, our troubles were not ended, for the path was a series of buffalo wallows. (…) Alternately slipping on wet ground and stumbling over unseen rocks, we at last came to some stone steps which took off from the path and went up to the right. Climbing these steps, we found a small courtyard, on the far side of which was a door. We had heard the gurgling of a hookah [water pipe] as we came up the steps, so I kicked the door and shouted to the inmates to open. As no answer came, I took out a box of matches and shook it, crying that if the door was not opened in a minute, I would set the thatch alight. On this an agitated voice came from inside the house, begging me not to set the house on fire. (…) A minute later, first the inner door and then the outer door was opened, and in two strides Ibbotson and I were in the house, slamming the inner door, and putting our backs to it.

There were some twelve or fourteen men, women, and children of all ages in the room. When the men had regained their wits after the unceremonious entry, they begged us to forgive them for not having opened the doors sooner, adding that they and their families had lived so long in terror of the man-eater that their courage had gone. Not knowing, what form the man-eater might take, they suspected every sound they heard at night. In their fear, they had our full sympathy, for from the time Ibbotson had slipped and broken the mantle, and a few minutes later had extinguished the red-hot lamp to prevent it bursting, I had been convinced that one, and possibly both, of us would not live to reach the village.”

However, due to loss and fragmentation of its habitat, and to some degree also poaching, the population has declined dramatically over the last fifty years. In 2015, it was estimated that between 700 and 950 leopards were living in the wild on the island.