Monkeys and apes

These young orphaned orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, Sabah, Borneo, love to be driven in a wheelbarrow into the rainforest, where they learn to climb trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A red spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi ssp. ornatus), also called black-browed spider monkey, feeds on coffee-like fruits, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) at Angkor Thom, Cambodia, is hanging upside down in a branch, before letting go and dropping headlong into a pond below. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Two northern plains langurs (Semnopithecus entellus), outlined against the light, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A young Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus), living on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain, seems to ask his friend, “Have you found something interesting?” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

”We are monkeys with money and guns.”

Tom Waits (born 1949), American singer, musician, composer, songwriter, and actor.

Monkeys are our nearest relatives – in fact, scientifically speaking, we are a species of ape, so it is quite true, what Tom Waits says.

The main source used on this page is the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: iucnredlist.org.

Hominidae Apes and Man

Traditionally, the apes, i.e. the chimpanzee, the bonobo, the orangutans, and the gorillas, were placed in the family Pongidae. However, genetic research has had the effect that apes and humans are now placed in the same family, Hominidae.

In fact, we are so closely related to the chimpanzee and the bonobo that we should belong to the same genus. As humans were described scientifically before the chimpanzee and the bonobo, they ought to be renamed Homo troglodytes and Homo paniscus, respectively! A number of religious people might find that offensive, so the step has not (yet) been made.

All species of apes have been declining drastically in the last hundred years due to poaching, infectious diseases, and loss of habitat, caused by expanding human activities. Although conservation efforts have increased significantly in recent years, it is assumed that this decline will continue, due to the rapid growth of human populations, felling of forests, lack of law enforcement due to corruption, and political instability in some countries. Some animals are still caught for zoos, and many are shot for the commercial bushmeat trade in certain African countries.

Gorilla Gorillas

There is an interesting story behind the name gorilla. The famous Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484-425 B.C.) relates travels, made by sea-faring Phoenicians of Carthage, including an expedition along the west coast of Africa c. 500 B.C., led by Hanno the Navigator. In an area, which is today Sierra Leone, members of this expedition encountered “savage people, the greater part of whom were women, whose bodies were hairy, and whom our interpreters called gorillae.”

This word was later used by American physician and missionary Thomas Staughton Savage (1804-1880) and naturalist Jeffries Wyman (1814-1874), when they described the gorilla in 1847, calling it Troglodytes gorilla. (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gorilla)

Previously, gorillas were regarded as belonging to a single species, Gorilla gorilla, but they have since been divided into two species, the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), with two subspecies, the lowland gorilla (gorilla) and the Cross River gorilla (diehli), and the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei), likewise with two subspecies, the mountain gorilla (beringei) and Grauer’s gorilla (graueri).

The western gorilla is found in Cameroun, Central African Republic, Gabon, and the Republic of Congo, with tiny populations in eastern Nigeria and northern Angola. The population of subspecies gorilla is probably around 250,000 individuals, whereas subspecies diehli is seriously endangered, counting only about 300 individuals. The population reduction of this species, in its widest sense, is predicted to exceed 80% by 2070, due to illegal hunting, disease (Ebola virus), and habitat loss.

The eastern gorilla lives in montane forests of eastern Zaire, north-western Rwanda, and south-western Uganda. This region has been subject to war and civil war for many decades, during which gorillas also fell victim. Subspecies beringei, which counts only about 900 individuals, is the only great ape that has increased in number lately, whereas subspecies graueri has been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for commercial trade of bushmeat. This illegal hunting has been facilitated by a proliferation of firearms from the various wars of this region. Previously estimated to number around 17,000 individuals, recent surveys show that Grauer’s Gorilla numbers have dropped to only about 3,800 individuals.

Resting female mountain gorillas, Bwindi National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young mountain gorilla is approaching us to investigate. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pan Chimpanzees

This genus contains 2 species, the chimpanzee (below) and the bonobo (Pan paniscus). The latter is restricted to rain forests south of the River Congo in Zaire. It is endangered due to habitat destruction and poaching for bushmeat.

In Ancient Greek mythology, Pan is the god of forests, and also of shepherds and their flocks of animals, and of rustic music (he plays a wind instrument with multiple tubes, called a pan flute). He is also companion of the nymphs. He has a human torso, but the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat.

Pan troglodytes Chimpanzee

Divided into 4 subspecies, the chimpanzee has a discontinuous distribution, from southern Senegal eastwards across the forested belt north of the Congo River, to the extreme western Tanzania and Uganda. They live in various types of forest, along rivers in savanna woodland, and sometimes in farmland, from the lowland up to an elevation of about 2,800 m.

Today, the total population is probably less than 400,000 individuals. Many populations are endangered due to habitat destruction and poaching for bushmeat.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘one who dwells in holes’ – an odd name, as chimpanzees definitely do not dwell in holes or caves. The English name is derived from the Tshiluba word chimpenze, meaning ‘ape’.

The chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania, were made famous by celebrated primatologist Jane Goodall (born 1934) – the first person to study these apes in depth. This picture shows a large male, named Everett, photographed in 1989. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pongo Orangutans

Formerly, orangutans were regarded as a single species, Pongo pygmaeus, which was confined to rainforests of Sumatra and Borneo. Lately, however, it has been split into three separate species. The Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), comprising 3 subspecies, is still widespread in Borneo, whereas the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii) is restricted to northern Sumatra, primarily the Aceh Province. The Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), which lives in an area of just 1,500 km2 in Batang Toru, south of Lake Toba, Sumatra, was described as a distinct species as late as 2017. They all live in lowland rainforest, rarely found above 500 m altitude, the Sumatran orangutan occasionally up to c. 1,500 m.

All three species are seriously endangered due to habitat destruction and fragmentation, and illegal poaching for zoos. It has been estimated that the population of the Bornean orangutan in 1973 was about 300,000 individuals, and it is assumed that this number will decline to c. 50,000 by 2025. The Sumatran orangutan has an estimated population of fewer than 14,000, and it is predicted that this number will decline by 80% by 2060. The population of Tapanuli orangutan is fewer than 800, and this number is still decreasing.

In 1985, I visited the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre in Sabah, Borneo. This centre is home to a number of orphaned orangutans, which were confiscated from poachers, who shot their mothers to get hold of the young. This centre, where the young ones are trained to a life in the wild, is presented in depth on the page Travel episodes – Borneo 1985: Visiting orangutans.

At the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, orphaned orangutans are trained to a life in the wild. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lacking a mother, the orphaned young often become much attached to one another. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

An adult male, now living in a semi-wild state near the centre. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This orangutan in Chengdu Zoo, Sichuan Province, China, is trying to get something outside its cage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old World monkeys

Cercopithecidae

This large family, comprising 24 genera and about 140 species, is widely distributed in Africa and Asia. Members include baboons, macaques, colobus monkeys, langurs, and many others.

Cercopithecus Guenons

This large group, comprising c. 25 species, is distributed in most of sub-Saharan Africa. They live in evergreen forests, sometimes in secondary forest and scrubland, mainly in the canopy, occasionally coming to the ground. They are dependent on daily access to water.

The generic name is derieved from Ancient Greek kerkos (‘tail’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), thus ‘(long-)tailed monkey’.

Cercopithecus mitis Blue monkey

Despite its name, this monkey is not really blue, but its grey fur has a bluish tinge to it. In its widest sense, this species, which is also called diademed monkey, comprises 17 subspecies, of which Sykes’ monkey, ssp. albogularis, silver monkey, ssp. doggetti, and golden monkey, ssp. kandti, are sometimes treated as separate species.

These monkeys are widely distributed, from Angola and Zaire eastwards to the Indian Ocean and Zanzibar Island, and from Ethiopia southwards to eastern South Africa, from sea level up to 3,800 m. To some degree, they are threatened by deforestation and habitat fragmentation, and in places by hunting for food and traditional medicine.

The specific name is Latin with many meanings, in this connection probably meaning ‘gentle’.

Blue monkey, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. In the lower picture, it is feeding on swarming termites together with an olive baboon (Papio anubis). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chlorocebus Green monkeys

Previously, these monkeys were included in Cercopithecus, where they were regarded as a single species, the green vervet (Cercopithecus aethiops), which was divided into 6 subspecies. Today, these subspecies are generally regarded as full species, the vervet (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), the grivet (C. aethiops), the green monkey (C. sabaeus), the tantalus monkey (C. tantalus), the Bale Mountains vervet (C. djamdjamensis), and the malbrouck (C. cynosuros), although some authorities still regard them as a single species.

Unlike the guenons, green monkeys spend much time on the ground in the daytime, sleeping in trees at night. They are also dependent on daily access to water.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khloros (‘green’) and kepos, a type of long-tailed monkey.

Chlorocebus pygerythrus Vervet

This species is distributed from Ethiopia and southern Somalia southwards through Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, and Botswana to South Africa. It lives mainly in savanna and open woodland, almost always near rivers, but is extremely adaptable and able to survive in cultivated areas, and sometimes in towns. There are no major threats to this species, although many are shot in agricultural areas, where they do damage to crops. It is also hunted as bushmeat in some areas.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek pyge (‘rump’) and erythros (‘red’), alluding to the rump having a reddish tinge.

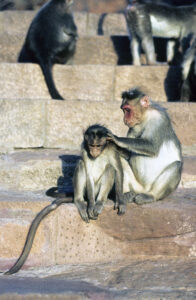

Grooming troop of vervet monkeys, Victoria Falls National Park, Zimbabwe. Note the pale blue scrotum of the male. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colobus Black-and-white colobus monkeys

Colobus monkeys are a group of African leaf-eating monkeys, which are also called thumbless monkeys, as their thumb is reduced to a stump. The word colobus is from the Greek kolobós, meaning ‘docked’. They mainly live in forests, but may occasionally stray into scrubland and plantations.

This genus contains 5 species, widespread in sub-Saharan Africa. Other colobus monkeys are placed in the genus Piliocolobus (below), and a single species in the genus Procolobus, the olive colobus (P. verus).

Colobus guereza Eastern black-and-white colobus

This species, comprising 8 subspecies, is also known as mantled guereza, a name alluding to the long fringes of white hair along each side. The tail also has a large white tuft. It is widespread in Africa, found from Cameroun east across southern Chad, Central African Republic, and northern Zaire to Uganda, Kenya, northern Tanzania, and Ethiopia.

In parts of its range, this species is threatened by habitat loss due to lumbering, establishment of plantations, and conversion to agricultural land. Hunting is rampant in some areas of the western part of its range.

The specific name is the Ethiopian word for colobus monkeys.

In 1988, during a stay in Arusha National Park, northern Tanzania, my companion Thomas Bregnballe and I were camping on a beautiful spot at the foot of Mount Meru, beneath a couple of huge trees, entwined by strangler figs. On our first night here, we were a little alarmed by an unbelievably powerful noise, coming from these trees, sounding like a mixture of some gigantic croaking frog, and a car engine that won’t start. As it turned out, the source of this sound was a troop of Kilimanjaro black-and-white colobus, subspecies caudatus, which used these trees as night roost.

Kilimanjaro black-and-white colobus, ssp. caudatus, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erythrocebus Patas monkeys

A small genus with 3 species, the common patas monkey (below), the Blue Nile patas monkey (E. poliophaeus), which is found in Ethiopia and Sudan, and the critically endangered southern patas monkey (E. baumstarki), which is restricted to a few areas in Tanzania.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek erythros (‘red’) and kepos, a type of long-tailed monkey. The name refers to the reddish coat of these monkeys.

Erythrocebus patas Common patas monkey

This species is widespread across the Sahel zone of sub-Saharan Africa, from southern Mauritania, Gambia, and Senegal, eastwards to western Ethiopia and northern Zaire, Uganda, and Kenya, with isolated populations elsewhere in Kenya, in northern Tanzania, and on the Air and Ennedi Massifs in the Sahara.

It lives in savannas and dry woodland, being commonest in woodland with scattered acacias. In some areas, it is threatened by habitat loss due to increasing desertification, and occasionally it is hunted for food or shot as a crop pest.

The specific name is the Wolof name of this species.

This sweet and gentle female patas monkey is for sale in the city of Bangui, Central African Republic. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca Macaques

The number of species in this genus has been growing steadily in later years to 23, as two new species have recently been described, the Arunachal macaque (M. munzala) in north-eastern India in 2004, and white-cheeked macaque (M. leucogenys) in south-eastern Tibet in 2015.

The generic name stems from the word makaku, plural of kaku, a West African Bantu name for a species of mangabey. In Portuguese, makaku became macaco, and in French macaque, the latter adopted by the British. In 1798, French taxonomist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825) applied this word, in the form Macaca, to the Barbary macaque (M. sylvanus, below) – the only species of the group living outside Asia, found in the Atlas Mountains of north-western Africa, with a feral population on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain.

Macaca assamensis Assamese macaque

This monkey is quite similar to the well-known rhesus macaque (below), but has a longer tail, and it lacks the orange hindquarters of that species. It is distributed from western Nepal eastwards to south-western China, and also has populations in Indochina and Bangladesh.

It generally lives in forests at altitudes between 200 and 2,000 m, but may be observed down to sea level in Bangladesh, and it occasionally strays to high mountains, sometimes as high as 4,000 m. It is declining in many places due to hunting and habitat fragmentation.

Members of a troop of about 50 Assamese macaques, observed near Pairo, Lower Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca cyclopis Taiwan macaque

As its name implies, this monkey is endemic to Taiwan, where it is quite common. It mainly lives in various primary forest types, but may also be found in secondary forest, from where it enters agricultural areas, and even towns, in search of food. In later years, it has become a big nuisance in many areas, but is not harmed, partly because it is protected by law, partly because of the widespread Buddhist conception that you should not kill animals.

The Taiwan macaque occurs from sea level up to an elevation of about 3,600 m, but is most common between 1,000 and 1,500 m. There are no major threats to the species.

The specific name refers to the cyclops, a one-eyed giant from the Greek mythology. Why the name was applied to this monkey is hard to see.

In Japan, small populations have been established from zoo escapes and deliberate releases. As it may pose a threat to the gene pool of the endemic Japanese macaque (M. fuscata) by hybridization, eradication programs have been initiated.

The fur of the Taiwan macaque is pale grey with a brownish tinge here and there. This large male is resting on a rock along a trail in the Bagua Shan Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female, grooming its young, Bagua Shan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A troop of Taiwan macaques, Sheding Nature Trail, Kenting National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young Taiwan macaque is feeding on leaves, Tacijili River, Taroko Gorge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is clinging to a rock face near Tataja, Yushan National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In many places, people feed Taiwan macaques, which has caused them to lose their fear of humans. This male in Yangminshan National Park doesn’t even bother to give way to a passing motorcyclist. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca fascicularis Long-tailed macaque

Among the macaques, this species, which is also called crab-eating macaque, is the most widespread, found from Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam southwards to the Indonesian Archipelago, and thence eastwards to the Philippines.

The long-tailed macaque lives in a wide range of habitats, including mangrove, forests, agricultural areas near forest, and temple groves. In the Philippines, it is found at elevations up to 1,800 m, in Indonesia up to 1,000 m, and in Thailand up to 700 m, whereas in Cambodia and Vietnam it generally occurs below 300 m. In the Philippines, some populations are threatened by hunting.

It is rather puzzling, why Sir Thomas Raffles (1781-1826), Lieutenant-Governor of British Java 1811-1815, and Governor-General of Bencoolen (on Sumatra) 1817-1822, applied the specific name fascicularis (‘with a small band or stripe’) to this species, as it does not have any stripes.

The following pictures are all from the so-called ‘Monkey Forest’ in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, a forested area around the Hindu temple Wenara Wana, which is home to several troops of these monkeys.

King of the ‘Monkey Forest’. – Resting on a wall, this large male long-tailed macaque is scratching his tail. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Females, dozing on a wall. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female long-tailed macaques are loving mothers. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female, grooming another female. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female, grooming a male on a sculpture, depicting a water buffalo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female is also grooming a male – whereupon he mounts her. She seems to dislike it. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young monkey is stuffing its mouth with bananas. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young at play. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaques start climbing at a very young age. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Most macaques love swimming. This one seems to tell me, “This is nice! You should try!” (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

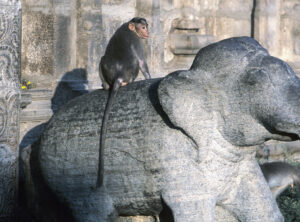

In this picture, a young long-tailed macaque is sitting on a sculpture, depicting – a long-tailed macaque. Other pictures, showing sculptures depicting this species, may be studied on the page Culture: Folk art around the world. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The macaques in ‘Monkey Forest’ are indeed used to tourists. The sculpture in the background in the upper picture below depicts Varaha, one of the supreme Hindu god Vishnu’s avatars (incarnations), a gigantic boar, who kills the terrible demon Hiranyaksha.

Vishnu and other Hindu deities are presented in depth on the page Religion: Hinduism.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca mulatta Rhesus monkey

Here we go in a flung festoon,

Half-way up to the jealous moon!

Don’t you envy our pranceful bands?

Don’t you wish you had extra hands?

Wouldn’t you like if your tails were – so –

Curved in the shape of a Cupid’s bow?

Now you’re angry, but – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

Here we sit in a branchy row,

Thinking of beautiful things we know;

Dreaming of deeds that we mean to do,

All complete, in a minute or two –

Something noble and grand and good,

Won by merely wishing we could.

Now we’re going to – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

All the talk we ever have heard

Uttered by bat or beast or bird –

Hide or fin or scale or feather –

Jabber it quickly and all together!

Excellent! Wonderful! Once again!

Now we are talking just like men.

Let’s pretend we are – never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind!

This is the way of the Monkey-kind.

Then join our leaping lines

that scumfish through the pines,

That rocket by where, light and high, the wild-grape swings,

By the rubbish in our wake,

and the noble noise we make,

Be sure, be sure, we’re going to do some splendid things!

Road song by the Bandar-log, from The Jungle Book (1894), by English writer Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936). In Hindi, bandar-log means ‘monkey-people’.

The rhesus monkey is the well-known brown monkey of northern India, in Hindi called bandar. It is found almost everywhere in the country north of the rivers Tapti in Gujarat and Godavari in Maharashtra. The total distribution area stretches from Afghanistan eastwards through Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and the northern part of Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos to Vietnam, and thence northwards to central China.

Its fur is mainly brown, with yellowish-orange hind parts, and the tail is rather short, 20-30 cm. This monkey lives in very diverse habitats, from semi-desert via various forest types to temple groves and cities, from the lowland up to altitudes around 2,500 m.

Following a strong decline due to felling of forest, combined with export of many animals for medical research, the rhesus monkey is now expanding in India, with an estimated population of 500,000 individuals, or more. This expansion is mainly due to the fact that it has adapted to a life in cities.

The size of a territory of a typical troop of rhesus monkeys has been measured at up to 16 km2 in montane forest, and 1-3 km2 in other types of forest, whereas in Kolkata, a troop of 62 individuals was studied, thriving successfully in an area of less than 4 hectares, in the centre of this metropolis.

In some areas, especially in Laos and Vietnam, the species is hunted for food, and habitat destruction has also affected populations locally in Indochina.

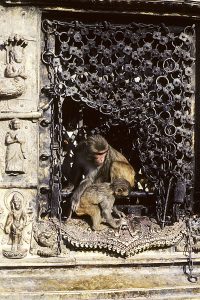

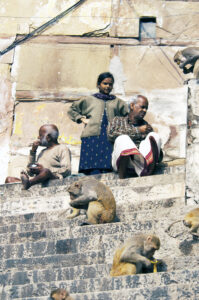

In the great Hindu epic Ramayana, the monkey army, led by Hanuman, plays a significant role, and for this reason monkeys are regarded as sacred animals among devout Hindus. Troops of rhesus monkeys, bonnet macaques (below), and northern plains langurs (below) often live around temples, where part of their diet consists of rice, sweets, or other edibles, brought as offerings to the gods.

Examples of such temples are Pashupatinath, a Hindu temple on the shores of the Bagmati River, Kathmandu, the Manakamana Kali Temple in central Nepal, and the great Buddhist stupa Swayambhunath in Kathmandu, which also contains Hindu shrines.

The role of the monkey army in Ramayana is described at the bottom of this page, caption Hanuman, the monkey god.

In the West, the rhesus monkey has become well-known due to its usage in medical research, which detected the rhesus factor, an inherited antigen in the blood of humans.

The specific name is of unknown origin. The common name may refer to a person in Greek mythology, King Rhesus of Thrace, who sided with the Trojans during the Trojan War, related in the Iliad.

The fur on the rear part of the rhesus monkey is yellowish-orange. This one has found a garland of marigold flowers, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The behind of rhesus monkeys is reddish with two bare patches of skin that the animal sits on. – Swayambhunath, Kathmandu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkey, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These females are enjoying the evening sun, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. The one in front has a tiny young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, resting on a chorten (a Tibetan Buddhist shrine, similar to a stupa), Swayambhunath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

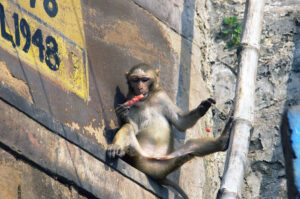

Clinging to a clothes-line, this one is looking through a window, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is walking along a narrow wall, surrounding the Hawa Mahal Palace, Jaipur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rhesus monkey is enjoying the morning sun, sprawled on a tree branch, where it spent the previous night, Uttarkashi, Garhwal, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys are true acrobats, sometimes walking on wires across roads or from one building to another, or even hanging upside down. – Son Tra, Da Nang, Vietnam (top), Haridwar, Uttarakhand (centre), and Swayambhunath, Kathmandu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female rhesus monkeys are affectionate mothers. These were photographed at the Manakamana Kali Temple (top), at Swayambhunath, and on Mount Popa, Myanmar (bottom). (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These young are riding on their mothers’ backs, Son Tra, Da Nang, Vietnam (top), and Swayambhunath, Kathmandu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys spend a considerable time grooming. – Son Tra, Da Nang, Vietnam (top), Swayambhunath (2nd from above), and Pashupatinath, Kathmandu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copulating rhesus monkeys, Swayambhunath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Females and young on a wall near the Ganges River, Varanasi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young rhesus monkey jumps from one wall to another, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young climbs from one branch to another, Son Tra, Da Nang, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, eating offerings of rice, Manakamana Kali Temple, central Nepal (top), and Swayambhunath. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhesus monkeys, gnawing banana peels, Varanasi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These rhesus monkeys are eating biscuits, presented by a tourist, Manakamana Kali Temple. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young rhesus monkey is eating a piece of watermelon, Varanasi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is eating acacia leaves, Mount Popa, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

One day, when I had visited the Swayambhunath Stupa, I was descending the staircase, when I heard a strange sound behind me. Turning around, I saw an empty Tuborg beer can come tumbling down the stairs, pass me, and come to a stop just in front of a rhesus monkey. The monkey grabbed the can, sniffed it, and then quickly dropped it, baring its teeth as if to say, “This stuff is not for me!”

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca nemestrina Southern pig-tailed macaque

Formerly, all pig-tailed macaques were regarded as a single species, M. nemestrina, but have now been split into two species, the southern, M. nemestrina, which is found on the Malacca Peninsula, and on Sumatra and Borneo, and the northern, M. leonina, which lives in Southeast Asia, from eastern Bangladesh southwards to the northern tip of the Malacca Peninsula, where its distribution overlaps with that of the southern species. Why they have been split, is a mystery to me, as they interbreed in the overlapping area.

Pig-tailed macaques are named for their short tail, which is often curved, resembling the curl on a pig’s tail.

The southern pig-tailed macaque, also known as Sunda pig-tailed macaque, is common in some places, but generally its numbers have decreased significantly due to habitat loss through logging and establishment of agricultural areas and oil palm plantations. It is frequently shot as a crop pest.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living in groves or forests’, derived from the name Nemestrinus, the Roman god of groves, from Ancient Greek nemos (‘grove’ or ‘wood’).

This man of the Minangkabau people, living in Maninjau, Sumatra, Indonesia, has trained a southern pig-tailed macaque to bring down coconuts from the trees. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca radiata Bonnet macaque

This macaque is restricted to the southern half of India, replacing the rhesus monkey south of the Tapti and Godavari Rivers. It is a little smaller than the rhesus monkey, its fur is greyish-brown, paler on the belly. It has an extremely long tail, longer than the body. On its crown is a cowlick, resembling a bonnet. The specific name also refers to the cowlick.

It is very common, locally abundant, living in all forest types, scrubland, plantations, agricultural lands, and urban areas. It is usually found below 2,000 m altitude, occasionally up to 2,600 m. As it often feeds in agricultural areas, conflicts with humans is an increasing problem. It is locally hunted, and many are caught for research, as well as for street performing.

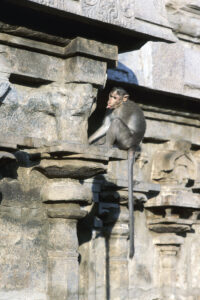

Whereas the temple monkeys in northern India are mainly rhesus monkeys, this role is taken over by bonnet macaques in southern Indian temples.

The bonnet macaque has a very long tail, longer than the body. This one, resting on a cornice in the Sri Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, is licking on a discarded drinking straw. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male bonnet macaque, resting in a growth of bamboo, Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque in Honnevara Forest, Karnataka, is trying to decide, whether I am dangerous or not. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female bonnet macaques are loving mothers. This one with a tiny young was observed at Azhiyar Ghat, Tamil Nadu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one at Singhur Ghat, Nilgiri Mountains, Tamil Nadu, is feeding on acacia seeds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sitting on our car, this one is gnawing on a banana peel, afterwards looking at its own reflection in the rear window. – Azhiyar Ghat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque is washing food in the Theppakadu River, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu, before eating it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A large troop of bonnet macaques live around the famous Hindu cave temples in the city of Badami, Karnataka. In this picture, several females and a young huddle together to keep warm in the morning cold. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Three females, one with a tiny young, Badami. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female is grooming another monkey, presumably its young, Badami. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young bonnet macaque, enjoying the evening sun, Badami. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Like most other macaques, bonnet macaques love bathing, as these young ones in the Theppakadu River, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu. After the bath, their ‘bonnet’ looks rather punky. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This bonnet macaque is crossing a heavily trafficked road in Badami by balancing on an electric wire, using its long tail as counter-balance. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At temples, food is always plentiful, and as the monkeys don’t move much around, they often become obese, like this one, observed in the Sri Minakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaques, which live near humans, often become scavengers, like this bonnet macaque in Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca silenus Lion-tailed macaque

This macaque is unique, as both male and female have a huge greyish mane around the head, which has given rise to its German name, Bartaffe (‘bearded monkey’). Apart from the mane, the fur is jet-black. The English name stems from another characteristic of this animal: the tuft at the end of the tail.

The lion-tailed macaque is endemic to rainforests of the southern part of the Western Ghats, in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. Although it is distributed in a huge area, the factual area of occupancy is small, as its habitat has been severely fragmented due to establishment of agricultural areas and plantations of tea, coffee, cardamom, and eucalyptus.

The total population of this animal is estimated at less than 4,000 individuals, made up of 47 isolated sub-populations. In one location, the Kodagu District, Karnataka, the species was formerly highly threatened by hunting for food. In later years, the population seems to have become stabilized due to better protection measures.

The specific name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek Seilenos, in Greek mythology tutor of the wine god Dionysus.

The pictures below are all from the Puthutottam Forest, Tamil Nadu, where a troop of lion-tailed macaques have become accustomed to people, as they are often being fed by tourists.

Lion-tailed macaques on the road through Puthutottam Forest, Tamil Nadu. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his huge canines, but he is probably just yawning, as this species is not at all aggressive towards people. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female with a young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This lion-tailed macaque is lying on the road, eating tiny pebbles, which make loud crunching noises between its teeth! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion-tailed macaque in its true habitat: rainforest. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca sinica Toque macaque

This reddish-brown monkey resembles the bonnet macaque, but the cowlick is further forward on its crown. It is restricted to Sri Lanka, where 3 subspecies are recognized, sinica in the dry zone of the eastern and northern parts of the island, aurifrons in the south-western lowland rainforest zone, and opisthomelas in the central highland wet zone.

It lives in a variety of forest types, from sea level up to about 2,100 m. The distribution areas of all three subspecies are very fragmented, and opisthomelas is restricted to an area of less than 500 km2, with only a fifth of this area actually occupied by the animals. The chief threat to this species is habitat loss due to establishment of plantations and agricultural lands. Many are shot, as they are doing considerable damage to crops.

The toque macaque is still widely distributed, but the population may have declined by more than 50% since 1975.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from China’. When Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the species in 1771, he must have been misinformed about the origin of it. The common name is a kind of hat without brim, of course referring to the ‘hair-style’ of this monkey.

The dry-zone race of the toque macaque, sinica, is found in the eastern and northern parts of Sri Lanka. This one was photographed at Polonnaruwa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young toque macaque, sitting between stilt roots of a banyan fig (Ficus benghalensis), Sigiriya, eastern Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young toque macaque at Polonnaruwa is drinking by dipping its hand into a puddle inside a hollow tree trunk, whereupon it licks its hand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Subspecies aurifrons is distributed in the south-western lowland rainforest zone. This one was observed in Sinharaja Forest Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca sylvanus Barbary macaque

This species is very characteristic, as it has no tail. It is the only surviving primate in Africa north of the Sahara Desert. In former times, it was widely distributed in south-western Europe and in north-western Africa, eastwards to Libya, but today it is restricted to small relict populations in Morocco and Algeria, where it occurs from sea level up to elevations around 2,600 m, mainly above 1,000 m. It prefers cedar forests, but is also found in oak forests, coastal scrub, and overgrazed rocky slopes with sparse vegetation.

Recently, the Moroccan population was estimated at 6,000 to 10,000 individuals, whereas in 1975 it was about 17,000. In Algeria, around 1980, the population was estimated at 5,500, but the present number is unknown. The total population may have declined by more than 50% since 1980, and the decline is expected to continue. All areas occupied by the Barbary macaque are under growing pressure from human activities.

There is also a small population of about 300 animals on the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Spain, which may, at least in part, be a remnant of the former European population. Historical sources, however, mention repeated release of African animals on the rock.

In his work from about 1610, Historia de la Muy Noble y Más Leal Ciudad de Gibraltar (’History of the Very Noble and Most Loyal City of Gibraltar’), Alonso Hernández del Portillo writes, “But now let us speak of other and living producers, which in spite of the asperity of the rock still maintain themselves in the mountain; there are monkeys, who may be called the true owners, with possession from time immemorial, always tenacious of the dominion, living for the most part on the eastern side in high and inaccessible chasms.” (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbary_macaques_in_Gibraltar)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living in forests’, derived from silva (‘forest’) and the suffix anus, meaning ‘from’ or ‘of the’.

Barbary macaque, sleeping on a wall atop the Gibraltar Rock. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female with young, Gibraltar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tourists used to feed the macaques on Gibraltar, but today this activity is strictly forbidden. However, the monkeys are still very tame, as this young one, pulling a boy’s ear. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papio True baboons

Baboons are native to Africa and south-western Arabia. They have long, dog-like muzzles, close-set eyes, and powerful jaws with huge canine teeth. Most authorities accept 6 species in this genus, others claim that they constitute a single species, as they often interbreed in overlapping areas of distribution.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for baboons.

Formerly, 3 other species were included in Papio, but have since been moved to other genera, the gelada baboon (Theropithecus gelada, below), the mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx), and the drill (M. leucophaeus).

Papio anubis Olive baboon

This species is named for its coat, which is grey with an olive tinge to it. It is the most widespread baboon, ranging throughout woodland and savanna from southern Mauritania and Mali eastwards to the Sudan, and thence southwards to Zaire and Tanzania. There are also isolated populations in the Tibesti and Air Massifs in the Sahara.

The olive baboon is also called Anubis baboon, alluding to the Egyptian god of embalming, who had the head of a jackal. The name refers to the dog-like muzzle of baboons.

It is a very adaptable species, able to survive in secondary forest and cultivated areas. Despite being considered a pest, which is trapped, shot, and poisoned in places, it is still locally common.

In a 200-km wide region in central Kenya, the olive baboon hybridizes with the yellow baboon, often making it difficult to allocate animals to one or the other species.

Olive baboons, resting in an African palmyra palm (Borassus aethiopum), Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is basking in the sand on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young baboons, playing in a vine, Gombe Stream National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young baboon, riding on its mother’s back, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is watching a pack of feeding banded mongoose (Mungos mungo) in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. These little carnivores are quite fierce, and the baboon made no attempt to steal their food, although he was clearly interested in it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Motherhood among olive baboons in Lake Manyara National Park. A subordinate female approaches another female with a tiny young, exposing its behind to the mother as a sign of submission, after which it is allowed to touch the baby. Note that the older female’s cheek pouches are filled with food. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papio cynocephalus Yellow baboon

The specific name of this animal is from the Greek kyon (‘dog’) and kephale (‘head’), like the name Anubis (see olive baboon above) referring to the dog-like muzzle of baboons. Its common name alludes to its grey fur, which has a yellowish tinge to it.

The yellow baboon is found from south-eastern Ethiopia and Somalia southwards to northern Mozambique, and thence across Malawi and Zambia to southern Zaire and northern Angola. Where possible, it prefers to live in Brachystegia woodland (miombo), but is also found in scrubland, savanna, and mangrove, and it is also able to survive in secondary forest and cultivated areas. There are no major threats to the species, although in some places it has been displaced by agriculture. Many are also trapped to be exported for medical research.

Yellow baboon, Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papio ursinus Chacma baboon

This baboon, comprising 2 or 3 subspecies, is restricted to southern Africa, found from southern Angola and southern Zambia southwards to the Indian Ocean. At present, it is not threatened, but due to the increasing human population, the baboons often feed in agricultural areas, where they do a great deal of damage. Many are shot or trapped, and an increasing number is killed by cars.

The specific name is derived from the Latin ursus (‘bear’), and the suffix anus, thus ‘bear-like’.

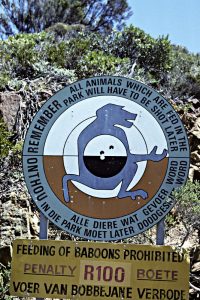

This sign in Cape of Good Hope National Park, South Africa, prohibits feeding of baboons. Where they are fed regularly by tourists, baboons often become aggressive and may have to be shot. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Piliocolobus Red colobus monkeys

This genus contains about 17 species, distributed in forests from Senegal eastwards to Central Africa, Zaire, Uganda, and Zanzibar.

Piliocolobus kirkii Zanzibar red colobus

As its name implies, this species is restricted to Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, where it lives in forests on the main island, Unguja. It may occasionally stray into plantations.

The total population is estimated at less than 2,000 individuals, and it is still decreasing due to habitat destruction, caused by timber felling, charcoal production, clearance for cultivation, and fires. Conservationists are working with the local government to devise an effective strategy to protect this species and its habitat.

It was named after physician, naturalist, and British Governor General of Zanzibar, Sir John Kirk (1832-1922), who was the first to raise awareness about this species. He was also the leading figure in ending the slave trade in Zanzibar, with the aid of his political assistant, Ali bin Saleh bin Nasser Al-Shaibani.

Portraits of Zanzibar red colobus. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is feeding on leaves of beach almond (Terminalia catappa). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pygathrix Douc langurs

A small genus with 3 species, native to Southeast Asia. They are all highly threatened in the wild.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pyge (‘rump’) and thrix (‘hair’), thus ‘with a (long-)haired rump’.

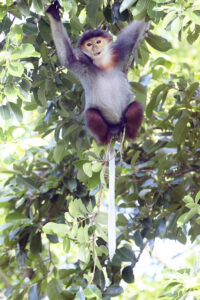

Pygathrix nemaeus Red-shanked douc

The red-shanked douc, which is native to Vietnam, southern Laos, and maybe north-eastern Cambodia, lives in primary and secondary rainforest, from the lowland up to an elevation of about 2,000 m. It is almost strictly arboreal, but may occasionally come down to drink or to eat soil with minerals.

It is highly endangered, threatened by habitat loss, and by hunting for food and traditional medicine. The total number is unknown, but it is believed that at least 700 individuals live in the Son Tra Nature Reserve near Da Nang, Vietnam.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek nemos (‘forest’).

Red-shanked doucs, Son Tra Nature Reserve, Da Nang. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Posters in and outside Son Tra Nature Reserve promote the conservation of this rare monkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Red-shanked doucs in a breeding centre for threatened primates, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus Typical langurs

This genus of leaf-eating monkeys contains about 8 species, all restricted to the Indian Subcontinent. In the past, all grey langurs living here were regarded as belonging to a single species, S. entellus, divided into six subspecies. However, recent morphological studies, combined with DNA-analyses, suggest that the grey langurs should be regarded as 6 full species: northern plains langur (S. entellus), terai langur (S. hector), pale-armed langur (S. schistaceus), Kashmir langur (S. ajax), black-footed langur (S. hypoleucos), and tufted langur (S. priam). A seventh species, dussumieri, has been declared conspecific with northern plains langur.

Today, most authorities consider all langurs on the Indian Subcontinent as belonging to the this genus. Formerly, two species, the Nilgiri langur (S. johnii) of south-western India, and the purple-faced langur (S. vetulus) of Sri Lanka, were regarded as members of the genus Trachypithecus (below),which is today considered to be distributed only in north-eastern India, Bhutan, and Southeast Asia.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek semnos (‘sacred’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), alluding to the sanctity of monkeys to Hindus (see caption Hanuman, the monkey god, at the bottom of this page).

Semnopithecus entellus Northern plains langur

This speciesis widespread in northern, central, and south-central India, from Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal southwards to Telangana and northern Karnataka and Kerala, with a small population in western Bangladesh, which probably originated from a single pair, introduced by Hindu pilgrims on the bank of the Jalangi River.

It is quite common, living in a variety of habitats, including forests, scrubland, temple groves, gardens, and towns, up to an altitude of c. 1,700 m. It is locally threatened by habitat loss due to intensified agriculture and fires, and by hunting for food by newly settled people in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.

Previously, western and southern populations of this species were regarded as a separate species, the southern plains langur (S. dussumieri), but recent genetic research has declared this name invalid.

In Hindi, Entellus is another name of Hanuman (see caption Hanuman, the monkey god, at the bottom of this page). In Greek mythology, Entellus was a Trojan or Sicilian hero. It is believed that the town of Entella in Sicily was named after him. He is mentioned in the poem The Aeneid, by Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), also known as Virgil.

Northern plains langurs in morning sun, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan. This species usually carries its tail arched over its back. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern plains langurs, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park. Note the many bees in the bottom picture. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troop of northern plains langurs, resting on a rock outside the sacred Udayagiri Caves, near Bhubaneswar, Odisha. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female outside the Udayagiri Caves has a tiny young. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Resting male, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his teeth as a sign of aggression, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pseudo-mating young, Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In many places, the northern plains langurs have adapted to a life in cities, where they often become a menace, stealing fruit or other edibles that are not guarded. Their status as sacred animals ensure that they are not harmed, despite their impudence. They are also common around temples, where they feed on rice and other edibles, brought by devout Hindus as offerings to the gods.

These northern plains langurs are sitting on a roof top in the town of Pushkar, Rajasthan, from where they, like a bunch of street urchins, survey the surroundings for fruit or other edibles to steal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern plains langurs, resting in a pavilion near the sacred lake in Pushkar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is resting on a sculpture, depicting the bull Nandi, mount of the great Hindu god Shiva, Chittorgarh Fort, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A Hindu legend relates that a young man named Narad Muni went to participate in a Swayamwara, during which young girls can choose a husband. This young man was very proud of himself and was convinced that he was the most handsome among the men. However, as the day came to an end, he went away heartbroken, because none of the young girls had chosen him. On his way home, he got thirsty, so he went to a waterhole to quench his thirst. His reflection in the water told him that he now had a monkey’s head.

”His reflection in the water told him that he now had a monkey’s head.” – Sariska National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus hector Terai langur

This species is found in the Himalayan foothills, the terai, encountered up to an altitude of about 1,600 m, from Uttarakhand eastwards to south-western Bhutan. It mainly lives in forests, occasionally feeding in orchards and fields with crops. Its fur is thicker than that of the northern plains langur (above), but not as rich as that of the pale-armed langur (below).

The total number of terai langurs is probably only about 10,000 mature individuals, and the population is slowly declining, mainly due to habitat loss.

The specific name refers to a person in Greek mythology, Prince Hector of Troy, who was one of the foremost fighters among the Trojans during the Trojan War, related in the Iliad.

During an excursion with my Indian friend Ajai Saxena to Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, we had company of a couple of terai langurs, which took their seat on the roof of our car. Presumably, many car drivers feed these monkeys, but as we oppose the habit of feeding wild animals, we didn’t give them anything, and shortly after they disappeared, jumping into the trees. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus hypoleucos Black-footed langur

This monkey has jet-black hands and feet, contrasting sharply with its grey arms and legs. It occurs in the Western Ghats, from Goa southwards through Karnataka to Kerala. In some areas, it is seriously threatened by hunting, and it has already been extirpated from parts of the Brahmagiri Hills in Kodagu District, Karnataka.

Some authorities believe that the black-footed langur is a natural hybrid between the northern plains langur (above) and the Nilgiri langur (below), and others regard it as a subspecies of the former.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek hypo (‘beneath’) and leukos (‘white’), alluding to the whitish belly of this species.

The black-footed langur has jet-black hands and feet, contrasting sharply with its grey arms and legs. – Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-footed langur, eating leaves, Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one in Anshi National Park, Karnataka, is busy scratching itself. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is climbing up a dead bamboo stem, from which it jumps onto another one, Anshi National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Black-footed langur, eating flower buds of a silk-cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), Honnavar Forest, Karnataka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus johnii Nilgiri langur

This species is jet-black, with pale-brown fur on the crown and on a ruff around its face. It is restricted to the Western Ghats in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, where it lives in forests at elevations between 300 and 2,000 m.

Formerly, it was threatened by habitat loss due to mining, dams, and human settlement, and by hunting, but the latter has decreased in recent years due to better protection, and after the introduction of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act in 1972, the population has increased. Since the 1990s, it has been relatively stable, counting around 20,000 individuals.

Previously, this species was placed in the genus Trachypithecus (below).

The specific name honours German missionary and naturalist Christoph Samuel John (1747-1813), who worked for the Danish-Halle Mission in the Danish settlement of Tranquebar, Tamil Nadu, today known as Tarangambadi.

Nilgiri langurs, eating leaf buds, Periyar National Park, Kerala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiri langur, Eravikulam National Park, Kerala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus priam Tufted langur

Two subspecies of this monkey are recognized, priam, which occurs in several disjunct populations, from the southern shores of the Krishna River, Andhra Pradesh, southwards to the city of Madurai, Tamil Nadu, whereas subspecies thersites is found in parts of the Western Ghats, and in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. The affinity of some South Indian populations is not known, as they have been very poorly studied. Genetic research indicates that there are consistent differences between the two taxa, and maybe they will be split into two separate species in the future.

The tufted langur lives in forests, temple groves, gardens, and cultivated areas, in India up to altitudes around 1,200 m, in Sri Lanka up to about 500 m.

The specific name refers to Priam, in Greek mythology the legendary last king of Troy during the Trojan War.

Tufted langurs, subspecies priam, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langurs, seen as silhoettes against the light, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, Masinagudi, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. Spotted deer (Axis axis) are seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, Masinagudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male is baring his teeth as a sign of aggression, Masinagudi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, running full speed along a road, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tufted langur, ssp. thersites, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This is probably a hybrid between tufted langur and Nilgiri langur (above), Annamalai National Park, Tamil Nadu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus schistaceus Pale-armed langur, Nepal langur

This species is easily identified by its luxurious, pale grey fur and the large white ruff around its jet-black face. It has a wide distribution at mid-elevations in the Himalaya, mostly between 1,500 and 3,500 m, but occasionally up to 4,000 m, from Pakistan through India and Nepal to Bhutan and extreme south-eastern Tibet.

It mainly lives in lush monsoon forests, occasionally found in scrubland and agricultural areas. It is quite common, and the population is fairly stable. Threats include habitat loss through logging, fire, and human encroachment, and it is hunted in Tibet for usage in traditional medicine.

The specific name is derived from Latin, meaning ‘slate-coloured’ – very pale slate, one must say!

Part of a large troop of pale-armed langurs, resting and playing in a meadow, Ghora Tabela, Upper Langtang Valley, central Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pale-armed langurs, resting on a stone wall, Kuldi Ghar, Modi Khola Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male pale-armed langur, resting in a tree, Tadapani, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pale-armed langurs, Dodi Tal Lake, Upper Asi Ganga Valley, Garhwal, Uttarakhand. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is feeding on buds and flowers of Viburnum grandiflorum, Dodi Tal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Troop of pale-armed langurs, eating soil to obtain minerals, Banthanti, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus vetulus Purple-faced langur

Four subspecies of this langur are recognized, all restricted to Sri Lanka.

The nominate vetulus lives in an area of less than 5,000 km2 of rainforest in south-western Sri Lanka, up to an altitude of around 1,000 m. Where its natural habitat has been destroyed, it may live in gardens and plantations, but these habitats offer no long-term survival prospects for it. Subspecies nestor lives in a similar habitat, further north than vetulus, whereas philbricki is found in moister forests of the dry zone. Subspecies monticola is restricted to the montane forests of central Sri Lanka, at elevations between 1,000 and 2,200 m.

All four subspecies are endangered, as they are believed to have undergone a decline of more than 50% in the last 40 years due to habitat loss and hunting.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘old’. It probably refers to the large whitish beard of this otherwise dark monkey.

Like the Nilgiri langur (above), the purple-faced langur was formerly placed in the genus Trachypithecus.

Portrait of a captive lowland purple-faced langur, of subspecies vetulus or nestor, Sri Lanka. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The dry-zone subspecies of the purple-faced langur, philbricki, is found in forests of moister areas of the dry zone of Sri Lanka. These pictures are from Polonnaruwa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Theropithecus gelada Gelada baboon

This striking animal, the only member of the genus, is restricted to high grassland escarpments along deep gorges of central Ethiopia, at elevations between 1,800 and 4,400 m.

It is still widespread, but was much affected by droughts, which ravaged Ethiopia in the 1980s. From an estimated population of maybe 800,000 individuals, a present guesstimate says c. 200,000. Its habitat is being eroded as a result of agricultural expansion, as an increasing number of people are moving into the central highlands. In some areas, the grazing pressure is high, forcing the geladas to move to less productive grass slopes.

The generic name is from the Greek thero (‘beastly’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), alluding to the rather grotesque appearance of the male of this species. In Greek mythology, Thero was a fierce Naiad, nurse of the infant Ares, who later became god of courage and war, but also of civil order.

In the Simien Mountains, the gelada baboon is fairly common in some areas, here at Gosh Meda. The male has a huge mane on head and body. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the chest, males as well as females have a naked red skin patch, giving rise to an alternative name of the species, bleeding-heart monkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachypithecus Lutungs

This genus, counting 15 species, is distributed from Bhutan and north-eastern India eastwards to the southernmost parts of China, and thence southwards through Indochina to Java, Bali, and Lombok. Vietnam is home to 7 or 8 species, all of which are severely threatened in the wild, mainly due to habitat loss and hunting.

The generic name is derived from the Greek trach (‘rough’) and pithekos (‘monkey’), referring to the dense fur of some species in the genus.

Trachypithecus auratus Javan lutung

This langur is endemic to Indonesia, where it occurs on Java, Bali and Lombok, and some smaller nearby islands. It lives in mangrove and forests, up to an altitude of 3,500 m. This species is threatened by habitat loss due to expanding agriculture and human settlements, and by hunting for food. Many are also captured for the pet trade.

The coat is black with greyish underside. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden’, referring to the fact that the species was named after a rare golden variant.

Some authorities consider the western Javan populations a separate species, named T. mauritius. I wonder why, as they are extremely similar.

Javan lutung, photographed in the rain forest on the lower slopes of the Gunung Rinjani volcano, Lombok. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Javan lutung is for sale at a market in the city of Yogyakarta, Java. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachypithecus delacouri Delacour’s langur

This langur, which is endemic to northern Vietnam, is popularly called white-shorts langur, alluding to its characteristic white rear body. It is critically endangered, primarily threatened by hunting for traditional medicine, and also by loss of habitat. As of 2010, less than 250 individuals were believed to remain in the wild.

It was named in honour of French-American ornithologist Jean Théodore Delacour (1890-1985).

Delacour’s langurs, photographed in Van Long Nature Reserve. The population in this reserve may be the only one in Vietnam still large enough to remain viable. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachypithecus geei Golden langur

This species occurs only in Bhutan and adjacent parts of Assam, between the rivers Manas in the east and Sankosh in the west. It lives in forests along the foothills of the Himalaya up to elevations around 3,000 m.

Its total known range is less than 30,000 km2, and much of it is not suitable habitat. The estimated population is less than 1,200 individuals in India and around 4,000 in Bhutan. It has declined by more than 30% in the last 30 years and is expected to decline further due to habitat loss. The population in India is highly fragmented, with the southern population completely separated from northern populations due to the effects of human activities.

The population in Manas National Park, Assam, is threatened by hybridization with a close relative, the capped langur (T. pileatus). Formerly, these two species were separated by rivers, but a number of constructed bridges has now made it easy for them to cross these rivers.

The golden langur was described as late as 1956, but was known much earlier by naturalists, the earliest record being by R.B. Pemberton in a paper from 1838, Report on Bootan Indian Studies Past and Present. However, his work was lost and not rediscovered until the 1970s, and the golden langur was not mentioned again until 1907, when E.O. Shebbeare reported seeing a ’cream-coloured langur’ in the vicinity of Jamduar.

In 1919, a publication stated that a pale yellow-coloured langur was common in a district near Goalpara in Assam, and in 1947, C. G. Baron wrote: ”I saw some white monkeys (…) and, as far as I know, they are an undescribed species. Their entire body and tail are of the same colour – pale silver-golden, not unlike a blonde.”

A number of other sightings roused the interest of celebrated naturalist Edward Pritchard Gee (1904-1968), who observed and photographed three troops of golden langurs in 1953. He reported his results to the Zoological Survey of India, and in 1955 six specimens were collected. The species was described by Dr. H. Khajuria, who named it Presbystis gee, in honour of Mr. Gee.

Golden langurs, Manas National Park, Assam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

New World monkeys

Atelidae Spider monkeys, howler monkeys, and woolly monkeys

This family of New World monkeys contains 4 genera with about 26 species, living in forests from Mexico southwards to northern Argentina.

Alouatta Howler monkeys

These monkeys constitute a group of 15 species, distributed from south-eastern Mexico southwards to northern Argentina. They live in various types of forest, including mangrove and swamp forest. Threats to these monkeys include habitat destruction and human persecution for food, for the pet industry, and for zoos.

Howler monkeys are famous for their loud call, which can be heard almost 5 km away. They have an enlarged hyoid bone, which enables them to produce this incredibly loud noise. The main function of the howling is probably to guard the territory of the troop.

The generic name is a corruption of arawata, the Carib name of the Venezuelan red howler monkey (A. seniculus).

Alouatta palliata Mantled howler monkey

Comprising 5 subspecies, this monkey is widespread, distributed from south-eastern Mexico southwards to northern Peru. The golden-mantled howler monkey, subspecies palliata, is quite dark, with a rufous mantle along the sides, and a golden patch on the back. It ranges from extreme eastern Guatemala eastwards to eastern Costa Rica. It mainly lives in the lowland, occasionally found up to 2,000 m altitude.

The specific name is derived from the Latin pallium, a large cloak, worn by Greek philosophers. In this case, it refers to the tuft of long hairs on the sides of this animal.

Golden-mantled howler monkeys, feeding in a tree, near Bagaces, Guanacaste. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This tiny young is clinging to its mother’s tail, Bagaces. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A slightly larger young already shows great agility. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ateles Spider monkeys

Spider monkeys are a genus of 7 species, found from southern Mexico southwards to Brazil, living in the upper stratum of tropical forests. These monkeys are characterized by their disproportionately long limbs, which have given them their name, and their long, prehensile tail, which is used as a fifth limb. They live in bands, comprising up to 35 members, which will disperse during the day to feed.

All species of spider monkeys are threatened due to habitat destruction and hunting for food, and two species, the black-headed (A. fusciceps) and the brown (A. hybridus), are critically endangered.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ateleia (‘incomplete’ or ‘imperfect’), alluding to the reduced or non-existent thumbs of these monkeys.

Ateles geoffroyi Geoffroy’s spider monkey

This monkey, also called black-handed or Central American spider monkey, has 5 or 6 subspecies, distributed from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to Panama. It mainly occurs in evergreen rainforest, but may also be found in deciduous forest. The species is threatened due to habitat loss, which has been severe across its entire range. It is estimated that it has declined by as much as 50% during the last 50 years. Today, it mainly survives in protected areas.

Spider monkeys of the Yucatan Peninsula and northern Guatemala are variously treated as belonging to subspecies vellerosus or yucatanensis, the latter now discarded by a number of authorities, whereas animals from northern Costa Rica, known as the red spider monkey, belong to subspecies ornatus. This subspecies is illustrated at the top of this page.

The specific name was given in honour of French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), professor of zoology at the faculty of sciences at Paris. He was a member of Napoleon Bonaparte’s great scientific expedition to Egypt 1798-1801, in which about 151 scientists and artists participated. Saint-Hilaire was associated with the natural history and physics section of the Institut d’Égypte.

Yucatan spider monkey, using its tail as a fifth limb, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A young Yucatan spider monkey clings to its mother’s back, Tikal National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cebidae Capuchin monkeys and squirrel monkeys

Following a number of genetic studies, this formerly large family has now been reduced to 3 genera with about 29 species, found from Mexico southwards to northern Argentina.

Cebus Capuchin monkeys

This genus, comprising about 15 species, is distributed from Honduras southwards to Peru and Brazil.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kebos, the term for a kind of long-tailed monkey.

The word capuchin derives from a group of Franciscan friars, named the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, which arose in 1520, when Italian friar Matteo da Bascio claimed that God had informed him that the manner of life led by his contemporary friars was not the one, which St. Francis of Assisi had dictated. The friars of this order wear brown robes with pointed hoods, called capuche. When the conquistadors reached Central America late in the 15th Century, they noticed some small monkeys, whose colouring resembled these friars, so they named them capuchins. (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capuchin_monkey)

Cebus imitator Central American white-faced capuchin

This species is native to forests of Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and western Panama. It is quite common in Costa Rica, living in a varity of forest types, and it is often confiding.

In the West, it is one of the best known of all monkeys, as it was often the faithful companion of the organ grinder, who would walk from town to town, playing his organ, while his monkey would perform a dance.

Until recently, this animal was considered conspecific with the Columbian white-headed capuchin (C. capucinus), which is found in coastal areas from eastern Panama southwards to Ecuador.

Central American white-faced capuchin, biting off bark in search of food, Corcovado National Park, Peninsula de Osa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-faced capuchin, resting on a branch, Palo Verde National Park, Guanacaste. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is stuffing its mouth with fruit, Palo Verde National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

White-faced capuchin, feeding on fruits of a tree, Tortuguero National Park, Limón. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grooming white-faced capuchins, Tortuguero National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Monkeys and culture

In many countries, especially in India, monkeys play an important role in folklore and culture. The pictures in this section show a few examples.

The relief in the picture below, photographed in a Jain temple atop the rock Vindyagiri, Sravanabelagola, Karnataka, South India, depicts a bonnet macaque (Macaca radiata), embracing a jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus).

A collection of pictures, depicting marvellous Jain temples, are found on the page Religion: Jainism.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pictures below, from Taichung, Taiwan, show acrobats, dressed as monkeys, who perform various acts, such as walking on stilts while balancing eggs on a stick, and jumping through burning rings.

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In the village of Tortuguero, Limón, Costa Rica, I encountered this wall painting, depicting a golden-mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata ssp. palliata) and a brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus), having coffee under the following slogan, ‘Tortuguero es pura vida’ (‘Tortuguero is pure life’).

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sign outside a tour agency, likewise in Tortuguero, is advertising jungle trips, using a white-headed capuchin (Cebus capucinus) and a great curassow (Crax rubra) as eye-catchers. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This street entertainer in the city of Tirumalai, Andhra Pradesh, has caught two young bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata), training them to perform. They seem to be arguing about something. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

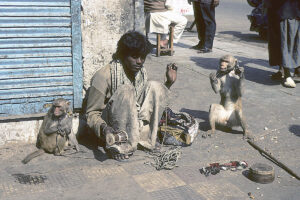

Another street entertainer with performing rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), Delhi, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The sculpture in the picture below, depicting smiling long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis), was observed in a Hindu temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. Other pictures, depicting monkey sculptures in Ubud, may be seen on the page Culture: Folk art around the world.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hanuman, the monkey god

In Hinduism, Rama is the seventh incarnation of the supreme god Vishnu, and main character in the great epic Ramayana. He was born as the son of King Dasharatha, who ruled the Kingdom of Koshada, northern India, and the king’s first wife, Queen Kausalya, and was thus destined to take over the kingdom in due time. However, in a moment of thoughtlessness, his father promised one of his other wives that her son should inherit the throne for 14 years, and that Rama should be expelled from the kingdom in this period. Rama knew of no other law than to obey his father, and he spent his exile wandering about in the forests with his chosen one, Sita, and his half-brother, Lakshmana.

One day, Sita was abducted by Ravana, a 10-headed and 20-armed demon king from Sri Lanka. Hanuman, leader of the monkey army, was a supporter of Rama, and he volunteered to go to Sri Lanka to negotiate Sita’s release.

It is told that during his stay in Sri Lanka, Hanuman stole mango fruits. For this sin, Ravana ordered him to be burned. Ravana’s soldiers tied a rag, soaked in oil, to his tail and set fire to it. During his attempt to extinguish the fire, Hanuman’s face and hands were blackened by the fire. The episode was noticed by the god of fire, Agni, who protected Hanuman from the heat, while the flaming tail, in retaliation, set many houses on fire. An enormous leap brought Hanuman back to India.

During the final battle, Rama managed to kill the evil demon king, and Sita was released. When the 14 years of exile had passed, Rama went home and assumed his throne.

As a reward for his services, Hanuman was raised to become a deity. He inspires strength in people, making him popular among men, whereas women generally regard him with mistrust, because he is unmarried. Due to the great deeds, performed by the monkey army in the Ramayana, monkeys are considered sacred among Hindus, and troops of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata), or grey langurs (Semnopithecus) often live around temples, where part of their diet consists of rice, sweets, or other edibles, brought as offerings by devout Hindus.

The legend informs us that Hanuman is a langur, which has black face and hands, and thus not a macaque, which is uniformly brown. Nevertheless, macaques are sacred animals on par with langurs.

The pictures below show various aspects of monkeys, referring to the Ramayana.

Sculpture in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, depicting the monkey god Hanuman, carrying Rama and Lakshmana on his shoulders, while trampling a demon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Balinese Keçak Dance (‘Monkey Dance’) depicts a scene from the Ramayana. Rama’s fiancée Sita has been abducted to Sri Lanka by the demon king Ravana, and Hanuman’s monkey army is trying to rescue her. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This detail of a Khmer relief in Banteay Srei, Angkor, Cambodia, depicts another scene from the Ramayana. The demon king Ravana is shaking the abode of the Hindu gods, Mount Kailash, making gods and animals horror-stricken, in this case Hanuman, a lion-headed deity, and the elephant-headed god Ganesh. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Hanuman sculpture outside a Hindu temple near Ubud, Bali, Indonesia, is covered in green algae and lichens. Rice and flowers have been brought to the image as an offering. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Over the years, the features of this Hanuman sculpture at the Pashupatinath Temple, Kathmandu, Nepal, have become blurred due to a thick layer of orange sindur (red powder, mixed with mustard oil), applied by devout Hindus during puja (worship). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture, depicting a warrior in Hanuman’s army, is guarding outside the Holy Water Temple in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded March 2018)

(Latest update March 2025)