Horse, donkey and mule

Horses are highly social animals, often grooming each other, as these Belgian horses, near San Simeon Creek, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horses in a snow-covered field, Manang, Upper Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

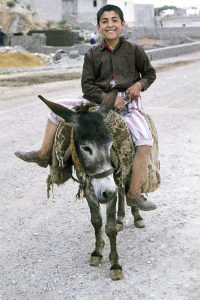

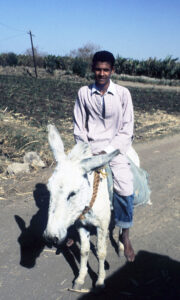

Today, donkeys are still used for riding in many countries. This picture shows a boy in the town of Birecik, southern Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mule train, returning without loads from the Upper Kali Gandaki Valley, Annapurna, central Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

With your mane unhogged and flowing,

And your curious way of going,

And that businesslike black crimping of your tail,

E’en with Beauty on your back, Sir,

Pacing as a lady’s hack, Sir,

What wonder when I meet you, I turn pale?

From the poem The Undertaker’s Horse (1885), by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), British journalist, writer and poet.

Modern horses (true horses, donkeys, asses, and zebras) evolved from a small, browsing animal, about the size of a fox, with four toes on the front feet and three on the hind feet. Initially, this creature, which first appeared in America about 55 million years ago, was named Eohippus (‘dawn horse’ in the Greek), later changed to Hyracotherium.

Recent research has now placed the type species, Hyracotherium leporinum, as the progenitor of both horses and brontotheres (extinct, rhino-like animals, which were closely related to horses), whereas other species, which were formerly placed in the genus Hyracotherium, have been moved to other genera, including Eohippus.

Over time, these early horses evolved into creatures with fewer toes, and about 5 million years ago, the modern Equus – the single-toed, fast-running animals that we know today – had evolved. During one of the ice ages, an early species of Equus reached Asia from America via a land bridge that formed between the two continents. From Asia, it spread to Europe and Africa. This progenitor evolved into the true horse (Equus ferus), and into various species of asses and zebras.

Wild horses in America died out gradually, most species presumably because of climate change. The last species, Equus scotti, was probably eradicated by invading nomad hunting tribes from Asia, who spread to America via the Bering land bridge during the latest ice age, about 12,000 years ago.

Tarpan and Przevalski’s horse

In Europe, the true wild horse, or tarpan (Equus ferus ssp. ferus), was also hunted to extinction, and the last one died in a Russian zoo in 1909. Przevalski’s horse, subspecies przewalskii, named after Russian geographer and explorer Nikolai Przevalski (1839-1888), only survived as scattered herds on the vast grass steppes in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia.

Przevalski’s horse also died out in the wild around 1960, but survived in zoos around the world. In later years, small herds of this horse have been released into the wild from breeding centres in Mongolia, and, once again, true wild horses roam the steppes of Central Asia.

Attempts have been made to recreate the tarpan by crossing Przevalski’s horse with various ancient types of domestic horses (E. ferus ssp. caballus), resulting in tarpan-like horses, such as the Konik horse. Today, herds of these ‘primitive’ horses have been released various places in Europe.

Givskud Zoo, Denmark, has a rather large population of Przevalski’s horse. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Apart from the long mane, the Konik horse resembles the extinct tarpan. A feral population of these horses live in the nature reserve Oostvardersplassen, Flevoland, Holland, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Domestication of the horse

Domestication of horses began on the Central Asian steppes around 4000-3500 B.C., and by 2000 B.C., domestic horses had spread to the major part of Europe. Initially, the horse was probably used mainly for meat and milk, the latter often fermented to make an alcoholic drink.

Later, people learned to ride on horses, and to utilize them for pulling wagons and the plough. Mongolian riders would often draw blood from their own horses and drink it – a quick and nourishing meal, when travelling. From the hides, numerous items were produced, including boots and gloves. Various tools were carved from the bones, and the hooves were boiled to make glue.

Today, horses are mainly used for sports and leisure, but in certain parts of the world, especially South America, cowboys still work on horseback.

The main difference in appearance between the wild horse and its domesticated cousin lies in the mane, which is short and upright in the wild horse, whereas it is long, hanging down one side of the neck, in the domestic horse. The coat also tends to be shorter in domestic horses, although in severe climates, they do grow thicker coats. The tarpan was dun-coloured, Przevalski’s horse is fawn, whereas the domestic horse comes in all sorts of colours.

A male horse is called a stallion, a female a mare, and their offspring a foal.

The mane is short and upright in the wild horse, whereas it is long, hanging down one side of the neck, in the domestic horse. – Belgian horse, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Foal, Le Grand Rocher, Plestin les Greves, Bretagne. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Exmoor pony is an ancient horse race, which is kept in semi-feral conditions several places in Europe. Its short mane is a wild-horse-like trait.

Semi-feral Exmoor horses in a large enclosure in the southern part of the island of Langeland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mare Exmoor with a suckling foal, Langeland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At a very early stage, people began using horses as pack and riding animals.

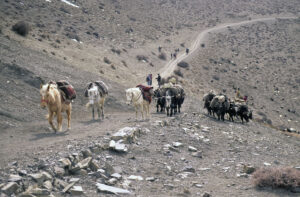

Caravan of loaded horses and dzopkios (crossbreeds between yak and cow), Jhong River Valley, Mustang, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pack horses, Monitor Pass, Sierra Nevada, California (top), and Shigatse, Tibet. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Farmer on his horse, Cordillera de Tilarán, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These riders participate in a horse race, which is held annually during the Catholic Festival of the Dead, in the town of Todos Santos, Guatemala. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tibetans, participating in an annual horse race, held in the Jhong River Valley, Mustang, central Nepal. The aim is, at full speed, to pick up a white scarf, a kata, from the ground. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

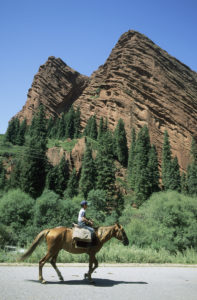

Horse riders at Djeti-Ögüz (‘Seven Bulls’), a rock formation located in the Issyk-Kul Province, Kyrgyzstan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horse riders in morning mist, Border State Park, south of San Diego, California. In the background the Mexican town of Tijuana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horse rider, pulling a skiing boy, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At an early stage, horses were also trained to pull wagons, and today, horse-drawn carriages are a common means of transportation around the world. Some types of carriages are called droshky, a word of Russian origin.

Horse carts are an important means of transportation on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Heavily loaded horse cart, between Larache and Rabat, Morocco. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

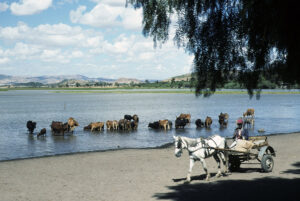

Horse wagon, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. Cattle are watered in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horse carts, crossing wooden bridges across canals in the town of Nyaung Shwe, Lake Inle, Myanmar. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tourists in Quebec, Canada, enjoying a trip in a horse-drawn carriage. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These horses pull a local type of carriage, called cidomo, in the town of Mataram, Lombok, Indonesia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The world population of horses is estimated at 58 million, and by far the highest number, about 9 million, are found in the United States.

Men, watering horses in a trough, Strymon River, Greece. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Modern horses first arrived in South America in the 1500s. These horses are grazing in a mountain meadow near Embalse El Yeso, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At dawn, this man leads his horse to the annual market in Sonpur, Bihar, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shoeing a horse, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horses, decorated for participation in a Daoist festival, Madou, Tainan, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Kyrgyz people (also Kyrghyz or Kirghiz) are a Turkic ethnic group, believed to have descended from the Yenisei Kyrgyz, who originated in central Siberia, around the Yenisei River. Later, this nomadic people spread to large parts of Central Asia, especially to the area, which is today called Kyrgyzstan.

Today, the Kyrgyz number about 5 million, of which 4.5 million live in Kyrgyzstan, sharing it with about 350,000 Russians.

In the summertime, a small number of Kyrgyz still live a semi-nomadic life. In this picture, a woman is milking a mare. Note the man’s typical felt hat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horse breeds

Many modern horse breeds descend from the Arabian horse, which originated in the Arabian Peninsula about 4,500 years ago. This large breed, which is characterized by strength, speed, and endurance, quickly became popular in many parts of the world.

The Frederiksborger is a Danish breed, which descends from the Arabian horse. In this picture, two Frederiksborgers are pulled from the stables to a watering trough at Melstedgård Agricultural Museum, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The small Icelandic horse is a direct descendant of the horses, which were brought to the island by Norwegian settlers about a thousand years ago. Today, it is forbidden to import horses to Iceland, as people here want to preserve the unique genes of the Icelandic horse.

Icelandic horse, Aðaldal, near Husavik, northern Iceland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Farmer Holmgrimur Kjartansson with three of his horses, Aðaldal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the Belgian horse originates in Belgium. It was developed as a draft horse and is one of the strongest horse breeds, which may weigh up to 900 kilos. One of its characteristics is the relatively long covering of hair, called feathering, on the pasterns (lower part of legs).

Belgian horses, Zealand, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a Belgian horse, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Norwegian fjord horse is a very old breed, which stems from the fiords of western Norway. Today, it is found in all of Norway and is regarded as a national symbol. It is a rather small, but very strong breed.

Norwegian fjord horse, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feral horses

Feral and semi-feral populations of the domestic horse are living in several countries, including the United States, England, France, and Australia. In numerous places, they are damaging the local ecology through overgrazing, and many environmentalists want their numbers reduced significantly.

Some populations are kept for historic or sentimental reasons, including the mustangs of western United States, the Chincoteague ponies on Assateague Island, Maryland, United States, and the Misaki ponies in Japan. Some of these populations are carefully managed to minimize their impact on the local environment.

The pictures below show Chincoteague ponies on Assateague Island. These horses may be feral, but you can hardly call them wild. They even often block the road, and drivers have to wait until they feel inclined to move. Early in the morning, in the campground, I was busy preparing breakfast outside our tent, when suddenly a large horse head appeared over my shoulder, snatching a bag of cereals out of my hand!

(Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Spaniards brought a breed of small, agile horses, called mestengo, to America, where the local native tribes quickly learned to ride on them. The Spanish name was since corrupted to mustang. Still today, descendants of these horses roam freely several places in western United States.

Mustangs, Monument Valley, Arizona. The rock formation in the background is called Three Sisters. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feral horse are also found in New Zealand. This sign was observed west of Turangi, North Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Horses in culture and art

Naturally, the horse has played an important role in numerous cultures and is often depicted in art.

Relief, depicting four horses, pulling a war chariot, Death Temple of Ramesses III, Medinet Habu, Luxor, Egypt. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Khmer Empire was a Hindu-Buddhist empire, centered around the city of Angkor, in present-day Cambodia. This empire lasted from around 802 to 1431 A.D.

This Khmer relief at Banteay Srei, Angkor, depicts a scene from the Hindu legend Fire in the Kandava Forest, in which horror-stricken people and animals, including a horse, elephants, deer, and lions, attempt to escape the fire. This legend is related on the page Religion: Hinduism. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture in the Sun Temple, Konark, Odisha (Orissa), India, dating from the 13th Century A.D., depicts the Hindu Sun God Surya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This sculpture, likewise in the Sun Temple at Konark, depicts a horse, trampling a monster to death. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This frieze in the Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh, India, dating from about 1000 A.D., depicts a rather special use of a mare. The man to the left seems to await his turn, while the embarrassed woman in the background is hiding her face. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

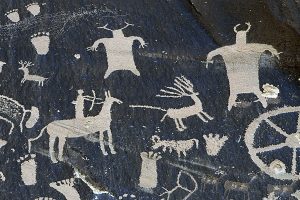

The images in the picture below are depicted on a boulder in Utah, United States, called Newspaper Rock. They depict various subjects, including a hunter, riding on a mustang, as well as deer, bighorn sheep, and shamans. These images have been made by scraping off a layer of so-called desert varnish on the rock, consisting of a thin layer of manganese and clay, formed through thousands of years by bacteria, which live on the rock surface. These bacteria absorb small amounts of manganese from the atmosphere and deposit it on the boulders. Other such images may be studied elsewhere on this website, see Culture: Folk art around the world.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Shuei woman in the Guizhou Province, China, is clad in traditional dress. The Shuei are renowned for their arts, and the woman is twisting horsetail hairs into thread, to be used for sewing colourful dresses and backpacks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Previously, wooden horses were a popular toy. This picture was taken in a veteran car museum on the island of Bornholm, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These kitschy paintings, depicting horses, were displayed for sale in Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Road sign, warning against horse carts, between Kavak and Havsa, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Donkey

A smaller cousin of the horse is the donkey, or ass (Equus africanus ssp. asinus), which is descended from the African wild ass (Equus africanus). Formerly, this species had a wide distribution, from Somalia north to Egypt, and westwards to the Atlas Mountains. Three subspecies are recognized.

The nominate subspecies, africanus, the Nubian wild ass, is presumably extinct, although a small population may survive in the Gabal Elba National Park, on the border between Egypt and the Sudan. However, the purity of these animals is questioned, as they may have interbred considerably with domestic donkeys. A feral population of asses live on the small Caribbean island of Bonaire, which may be closely related to the Nubian wild ass. (Source: retrieverman.net)

The Somali wild ass, ssp. somaliensis, is found in deserts and other arid areas of Somalia, Eritrea, and eastern Ethiopia, but in very low numbers – maybe a total of less than 600 individuals. Thus, it is critically endangered and may go extinct in the wild.

The Atlas wild ass, ssp. atlanticus, was once found across North Africa and in parts of the Sahara, but was extirpated by hunting. The last individuals may have been shot by Roman hunters around 300 A.D.

Domestication of wild asses

Asses were probably first domesticated around 4000 B.C. by pastoral tribes of Nubia, who used them as pack animals instead of cattle. Using donkeys made it possible for them to move around faster, when trading goods over long distances, as they now didn’t have to wait for the cattle to chew the cud.

During the Fourth Dynasty in Egypt (2675-2565 B.C.), wealthy people often owned more than a thousand donkeys, which were used for meat and milk, to pull carts and the plough, and as pack animals.

By about 3000 B.C., the donkey was a common animal in the Middle East, with the main breeding centre in Mesopotamia. By c. 1800 B.C., the donkey had spread further east in Asia, and by about 2000 B.C., it was also present in Europe.

The world population of donkeys is estimated at c. 40 million, with the majority in the developing countries. The highest number, about 11 million, used to be in Chinese territories, followed by Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mexico. However, the number in China has dropped significantly in later years.

A male donkey is called a jack, a female a jenny, and their offspring a foal.

This jenny and her foal are grazing in an alpine meadow in the Markha Valley, Ladakh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At a very early stage, donkeys were used as pack animals. These men in Kabul, Afghanistan, are loading sacks of garlic on donkeys, to bring them to a market. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

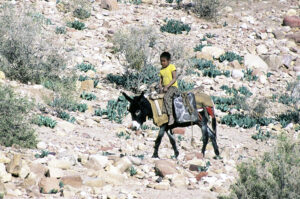

Today, donkeys are still used for riding in many countries. These pictures show boys in Petra, Jordan (top), and Luxor, Egypt. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Typical Greek road scene 40 years ago: The husband is riding a donkey, while his wife has to walk. – Lassithi Plain, Crete. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mother and daughter, south of Abalak, Niger. Note that the woman has placed a bowl on her head. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boys on a donkey, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. Cattle are watered in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

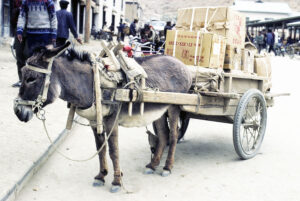

Donkey carts are still a common means of transportation in many countries. These pictures are from the town of Shigatse, Tibet. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Donkey team, pulling a harrow, Palapye, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

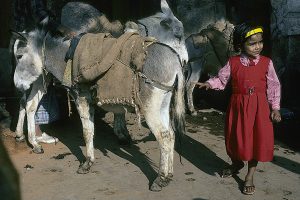

The parents of this little girl wanted to photograph her next to the donkeys. Apparently, she is a bit afraid of them! – Varanasi, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A burro named Prunes

The first donkeys in the Americas were brought to the island of Hispaniola in 1495, during the second voyage of Columbus. In Mexico, they probably arrived in 1528. From here, they quickly spread northwards, used as pack animals by soldiers, missionaries, and miners.

During the Gold Rush in the 19th Century, the donkey, or burro, as it was called, was the main pack animal. When the Gold Rush ended, many of these burros escaped, or were deliberately released, forming feral populations, which have existed until today.

One famous burro was Prunes, a donkey bought in 1879 by a miner named Rupe Sherwood, who was working near the towns of Fairplay and Alma, northern Colorado.

As it turned out, this little animal was worth far more than the 10$ he paid for it. Not only would it pull ore cars like any other burro – no, Sherwood trained it to go down alone to the general store, where the store keeper would read the note attached to the donkey, load the required goods into sacks on his back, and off he trotted, back up the mountain trails to his owner.

For many years, Prunes was shuffling back and forth with ore cars in the dark, damp passages, and soon he became the local miners’ pet. When he grew too old for the hard work, Sherwood freed him from collar and traces and set him free to roam at will. The burro spent its final years in Alma, begging for food, which was readily supplied by the residents. As Prunes approached his 60s, his health began to fail. He was losing his teeth, and with that his ability to eat proper food.

In 1930, a blizzard struck Alma, and as the temperature plunged below zero, Prunes took refuge in an old shed. During the blizzard, the door blew shut, and a snowdrift prevented the old burro from pushing the door open.

Soon, residents noticed that Prunes was not making his usual rounds. They found him half starved in the shed, unable to walk. Despite being pampered, he didn’t recover, and the residents, including Sherwood, decided to put an end to his sufferings. Initially, his carcass was dumped in the local garbage dump, but later his remains were buried in a grave on Fairplay’s main street, beneath a unique concrete monument, studded with ore samples from the mines where Prunes had worked.

A year later, at the age of 82, Rupe Sherwood died in the Fairplay hospital. Following his will, his ashes were interred beside the Prunes monument. (Sources: Ferguson 1993, Jessen 2017)

Today, many feral burros still live in western United States. This traffic sign in Death Valley National Park, California, is warning against crossing burros. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mules

Jacks are often crossed with mares to produce mules, which are sturdier and much stronger than donkeys. These mules are widely used as pack animals. If a jenny is crossed with a stallion, the offspring is called a hinny.

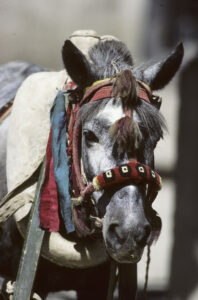

Himalayan mules are very sure-footed, as this picture from Ulleri, Annapurna, central Nepal, shows. The animal with the plume has a large bell attached, the purpose of which is to announce to hikers that a mule train is approaching. You then have time to get out of their way. If you don’t, you risk being pushed into the abyss! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mule trains, making their way down the Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna (top), and the Langtang Valley, both in Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

While the mule driver is having lunch, his mules are grazing, their burdens still attached, Banthanti, Annapurna. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

After carrying heavy burdens all day, these mules enjoy rubbing their back in a patch of sandy soil near Tal, Marsyangdi Valley, Annapurna. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mules, quenching their thirst in a pond, Langtang Valley, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Before the introduction of steel suspension bridges in the Himalaya, rivers were crossed on bridges made of bamboo poles, tied together with twine made from liana bark. After some years of wear and tear, these rather flimsy constructions would finally break, often causing casualties among men and beasts. Pictures depicting suspension bridges are shown on the page Culture: Bridges.

These mules, heavily loaded with planks, are crossing the Kali Gandaki River, Mustang, Nepal, on a steel suspension bridge. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

References

retrieverman.net/2015/02/26/are-the-bonaire-donkeys-the-last-wild-nubian-asses.

Ferguson, G. 1993. Rocky Mountain Walks. Fulcrum Publishing, Colorado.

Jessen, K. 2017. Burro named Prunes buried on street in Fairplay. (reporterherald.com/2017/01/27)

(Uploaded September 2017)

(Latest update October 2024)