Animal portraits

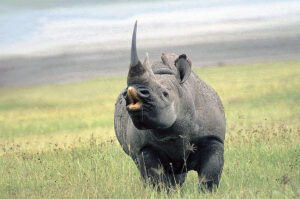

This bull black rhino (Diceros bicornis) is sniffing a tuft of grass, into which a female has urinated, baring its lips in a posture, called flehmen. The inhaled air passes a special sensing organ, which is able to detect whether the female is in heat. – Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Courting pair of Australian gannet, Muriwai Beach, New Zealand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This excited flap-necked chameleon (Chamaeleo dilepis), with expanded gular sack, displays numerous black spots, Masasi, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female dromedaries (Camelus dromedarius) are often affectionate towards each other. – Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mammals

Atelidae

This is a family of New World monkeys, comprising about 26 species, placed in four genera: Ateles (spider monkeys), Alouatta (howler monkeys), Brachyteles (woolly spider monkeys), and Lagothrix (woolly monkeys).

Ateles Spider monkeys

This genus of 7 species is found from southern Mexico southwards to Brazil, living in the upper stratum of tropical forests. These monkeys are characterized by their disproportionately long limbs, which have given them their name, and their long, prehensile tail, which is used as a fifth limb. They live in bands, comprising up to 35 members, which will disperse during the day to feed.

All species of spider monkeys are threatened due to habitat destruction and hunting for food, and two species, the black-headed spider monkey (A. fusciceps) and the brown spider monkey (A. hybridus), are critically endangered.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ateleia (‘incomplete’ or ‘imperfect’), alluding to the reduced or non-existent thumbs of these monkeys.

Ateles geoffroyi Geoffroy’s spider monkey

Six subspecies of this monkey, which is also called black-handed or Central American spider monkey, are distributed from south-eastern Mexico eastwards to Panama. It mainly occurs in evergreen rainforest, but may also be found in deciduous forest. The species is threatened due to habitat loss, which has been severe across its entire range. It is estimated that it has declined by as much as 50% during the last 50 years. Today, it mainly survives in protected areas.

The specific name was given in honour of French naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), professor of zoology at the faculty of sciences at Paris. He was a member of Napoleon Bonaparte’s great scientific expedition to Egypt 1798-1801, in which about 151 scientists and artists participated. Saint-Hilaire was associated with the natural history and physics section of the Institut d’Égypte.

This red-bellied spider monkey, ssp. frontatus, also called black-browed spider monkey, is feeding on coffee-like fruits, Tortuguero National Park, Limón, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bovidae Cattle etc.

This large family, comprising about 47 genera and c. 143 species, are cloven-hoofed, ruminant animals, including cattle, antelopes, sheep, goats, and many others.

Aepyceros melampus Impala

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Male impala, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Antidorcas marsupialis Springbok

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Springbok, Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bos bison American bison

The sad fate of this animal is described on the page Folly of Man.

American bison bull, rubbing on a fence, Badlands National Park, South Dakota, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bos grunniens Yak

The yak is a high-altitude species, which used to roam the Central Asian highlands in large numbers. It is adapted to a life in this harsh environment, having a luxurious fur, which keeps it warm in temperatures below -30o Centigrade. – A Nepalese legend, which explains how the yak got its rich fur, is related on the page Animals as servants of man: Water buffalo.

The yak was domesticated by nomadic tribes as early as c. 5000 B.C., and today the population is estimated at 14 million, the vast majority in Chinese territories. The population of wild yak may be fewer than 15,000, and though it is legally protected, illegal hunting still takes place and may threaten this magnificent animal with extinction.

The scientific name is Latin for ‘grunting ox’ – a most descriptive name, as it grunts incessantly.

Yak, resting in front of a barberry bush, Dingboche, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bos taurus Cattle

Cattle, including the zebu ox, are described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Inquisitive zebu ox, Pushkar, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zebu ox, dark morph, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

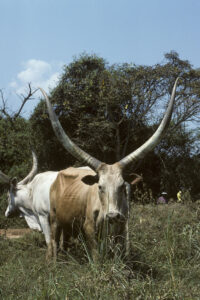

Longhorned Ankole cattle, an indigenous cattle breed of sub-Saharan Africa, Mubende, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Jersey is a British breed of small dairy cattle, originating from Jersey, one of the Channel Islands. Selective breeding has caused the milk production of these cows to increase to an average of 6,024 litres per year in the U.K., with some individuals yielding around 9,000 litres. The milk has a characteristic yellowish tinge and is high in butterfat (5.4%) and protein (3.8%).

As the Jersey adapts well to cold as well as hot climates, it has been exported to many countries around the world. Some countries have developed separate breeds.

Curious Jersey heifer, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the Scottish Highland cattle originated in the Scottish Highlands, or maybe in the Outer Hebrides, first mentioned in the 6th Century A.D. In Scots, it is called Heilan coo, a name of Norse origin, meaning ‘highland cow’, perhaps brought to Scotland by the Vikings.

This breed is characterized by the long horns and the wavy coat, which comes in a variety of colours, including red, ginger, black, dun, yellow, white, or grey. The long coat allows it to spend the harsh Scottish winter outdoors. It is raised primarily for the meat, which is prized for its low content of cholesterol, and also for the milk, which generally has a very high butterfat content.

Today, Scottish Highland cattle is found in many countries around the world.

Scottish Highland cattle, Öland, Sweden. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Capra Goats and ibex

This genus contains about 10 species, distributed in central Europe, Spain, north-eastern Africa, and large parts of Asia.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘female goat’.

Capra aegagrus ssp. hircus Domestic goat

The goat was among the earliest domesticated animals. About 8000 B.C., inhabitants of the Zagros Mountains in south-western Iran began domesticating the local wild goat, the Bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus). These Stone Age people were herding goats for their meat and milk, the pelt was used as clothing, tools were made from the bones, and the dung was used as fuel.

The domestic goat is still closely related to the Bezoar goat, which is named ssp. aegagrus, to distinguish it from the domestic goat, ssp. hircus. Over time, goats have been spread to most areas of the globe. Its total worldwide population is estimated at one billion, about half of which are in Asia.

A male goat is called a billy, or a buck, whereas a castrated male is a wether (like a castrated sheep). A female goat is a nanny or a doe. Young goats are called kids.

It is almost unbelievable, what goats are able to digest – bone-dry grass, thorny twigs, cardboard boxes. Indeed, in northern India, I once watched a herd of goat head straight for a growth of very poisonous thorn-apples (Datura stramonium) and commence eating the fruits. Apparently, goat stomachs can neutralize the toxins.

More about the domestic goat is found on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Mixed flock of goats and sheep, blocking a road, Col du Mt. Cenis, France. One goat is particularly inquisitive. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“Yummy! This cardboard box is really delicious!” – Izmir, Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Capra ibex Alpine ibex

At one point, this magnificent animal was almost hunted to extinction, only surviving in a few pockets in northern Italy. Due to the alarming decrease of the population, Victor Emmanuel, later to become king of Italy, declared the Royal Hunting Reserve of Gran Paradiso in 1856, and a protective guard was created for the ibex.

In 1920, King Victor Emmanuel III donated the original 21 square kilometres to the country, and it became Italy’s first national park in 1922. Despite the park, ibex were poached until 1945, when only 419 remained. Since then, the population has increased, and there are now almost 4,000 in the park. It has been reintroduced to numerous other areas in the Alps, and also to Bulgaria and Slovenia.

In summer, the alpine ibex lives in rocky areas just below the snow line, at elevations between 1,800 and 3,300 m, descending to lower altitudes in the winter.

The specific name is the classical Latin term for the chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), possibly of the same origin as Old Spanish bezerro (‘bull’). Why it was applied to this animal is not clear.

Male Alpine ibex, marked with an ear tag, Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Connochaetes taurinus Blue wildebeest

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

White-bearded wildebeest, subspecies mearnsi, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the annual wildebeest migration, these white-bearded wildebeest quench their thirst in the Grumeti River, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kobus ellipsiprymnus Common waterbuck, defassa waterbuck

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Male common waterbuck, ssp. ellipsiprymnus, chewing the cud, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Male East African defassa waterbuck, ssp. harnieri, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kobus kob Kob

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Male Uganda kob, subspecies thomasi, resting in tall grass, Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Madoqua kirkii Kirk’s dik-dik

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Kirk’s dik-dik, subspecies cavendishi, eating from a bush, Arusha National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nilgiritragus hylocrius Nilgiri tahr

This rare sheep is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Mammals in the Indian Subcontinent.

Several other pictures, depicting this species, are shown on the page Quotes on Nature.

Eravikulam National Park, Kerala, where this picture was taken, is a stronghold of the Nilgiri tahr, housing an estimated 700-800 individuals, app. one-fourth of the total population. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oreamnos americanus Mountain goat

Despite its name, this animal is not a true goat of the genus Capra, but is more closely related to serows (Capricornis), gorals (Naemorhedus), and the chamois (Rupicapra), sometimes referred to as goat-antelopes. It is endemic to mountainous areas of western North America, from southern Alaska southwards through western Canada to Oregon, northern Nevada, Utah, and Colorado.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oros (‘mountain’) and amnos (‘lamb’), thus ‘mountain lamb’, presumably alluding to the white fur of the animal.

Confiding female mountain goat, Mount Rushmore, Black Hills, South Dakota. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ovis Sheep

This genus contains about 7 species, distributed in the wild in Asia and North America, whereas the domesticated sheep is found in almost all corners of the world.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for sheep.

Ovis aries Domestic sheep

Sheep were among the first animals to be domesticated by humans, maybe as early as 11,000 to 9000 B.C., in Mesopotamia. The ancestor of the domestic sheep is still disputed, but today the most common hypothesis is that it is descended from the Asiatic mouflon (Ovis gmelini). Previously, it was assumed that it is descended from the European mouflon (O. aries ssp. musimon). However, today many authorities regard this species as an ancient breed of domestic sheep, which has turned feral.

A male sheep is called a ram, or tup, and a castrated ram is a wether. A female is called a ewe. This word is pronounced in various ways, often as ‘yo’ or ‘you’, in Scotland as ‘yow’ (rhyming on ‘how’). Young sheep are called lambs.

More about the domestic sheep is found on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Portraits of sheep, resting in the shade beneath an old oak, central Jutland, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ovis canadensis Bighorn sheep

Three subspecies of this impressive animal are widely distributed in mountains of western North America, from British Columbia and western Alberta southwards through the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada to Baja California, north-western Mexico, and south-western Texas, as far east as North and South Dakota. This species was once very numerous, but the population has been much reduced by overhunting and introduction of diseases from livestock.

The desert bighorn sheep, ssp. nelsoni, occurs throughout the desert regions of the south-western United States and north-western Mexico.

Ram of desert bighorn sheep, ssp. nelsoni, Tucson Desert Zoo, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Raphicerus campestris Steenbok

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Female steenbok, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tragelaphus scriptus Bushbuck

This antelope is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Antelopes.

Female bushbuck, Victoria Falls National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Camelidae Camels

The origin of camels, and their relationship with people, is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

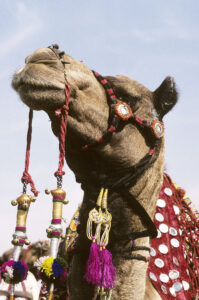

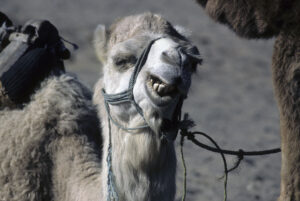

Camelus dromedarius Dromedary, one-humped camel

This species is extinct in the wild, but is widely distributed as a domestic animal, from India across the Middle East to the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, Somalia, and northern Kenya. It was probably first domesticated in Somalia or southern Arabia, around 3000 B.C.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek kamelos, the classical term for camels, originally from either Arabic jamal or Hebrew gamal. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek dromas (‘running swiftly’).

Portrait of a dromedary, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Decorated dromedary at a camel festival, Bikaner, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dromedaries, chewing their cud, Thar Desert, Rajasthan (top), and Sousse, Tunisia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When a dromedary bull is in heat, froth is oozing out of his mouth. – Bikaner, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Canidae Dog family

Many members of this family are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Dog family.

Canis lupus ssp. familiaris Domestic dog

The domestication of the dog and its long association with Man is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

This dog in Guiyang, Guizhou Province, China, may have some Tibetan spaniel genes, and probably also some Pekingese, due to its very prominent lower jaw. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I asked the owner of this little terrier in Taichung, Taiwan, why it was wearing sunglasses. She said that it was to prevent the dog from getting cataract. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The English Springer Spaniel is a hunting dog breed, descended from Norfolk or Shropshire Spaniels in the mid-1800s. It was traditionally used for flushing out game, and for retrieving it. Today, it is also a popular family dog.

During a research trip to the Chukotka Peninsula, north-eastern Siberia, my companions and I visited the staff of a light house, situated at the tip of Kosa Ruskaya Koshka (‘Russian Cat’s Sandspit’). One of the dogs belonging to the staff was an English springer spaniel. Our trip to this area is related in detail on the page Travel episodes – Siberia 2011: Caterpillar trip in Chukotka.

(Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The short-legged dachshund was developed to chase foxes and badgers out of their dens, for the hunter to shoot them. In America, they have also been used to chase prairie dogs out of their dens. This breed comes in three forms: smooth-coated, long-haired, and wire-haired.

Wire-haired dachshund, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Samoyed originated among the nomadic Samoyed people in Siberia, to pull sledges and to assist in the herding of reindeer. Today, it is a very popular family dog in the West.

Samoyed, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Rhodesian ridgeback is a large-sized dog breed, which originated as a cross between the ridged hunting dogs of the Khoikhoi people, and European dogs, brought to the Cape Colony of South Africa by the Boer. The name was instigated in 1922 in Bulawayo, South Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe).

Pup of Rhodesian ridgeback, chewing on a bone, Keetmanshoop, Namibia. Note the ridge along the spine. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The commonest type of stray dogs in Taiwan, generally called Taiwan dogs, or sometimes Takasago dogs, are a result of the indigenous Formosan hunting dogs interbreeding with imported dog types. Taiwan dogs are usually black or brown, or a mixture of the two.

During Chinese New Year, a red scarf has been tied around the neck of this c. 12-week-old Taiwan pup. A red envelope, on which is written wang-wang, has been fastened to it. The red colour of the envelope, as well as the text, denotes well-wishing. At the same time, wang-wang is an imitation of a dog’s barking. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Same dog as above, 3 years later. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lupulella mesomelas Black-backed jackal

In 2017, genetic research concluded that this species and the side-striped jackal (L. adusta) were only distantly related to members of the genus Canis, and, consequently, they were moved to a separate genus.

The black-backed jackal, also known as silver-backed jackal, is quite common in two widely separated areas. The nominate subspecies is distributed in southern Africa, from southern Angola, south-western Zambia, Zimbabwe, and southern Mozambique southwards to the Cape Province of South Africa, whereas subspecies schmidti is found from extreme south-eastern Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia southwards to central Tanzania, westwards to Uganda.

The generic name is derived from the Latin lupus (‘wolf’), and the suffix ella, indicating something diminutive, thus ‘little wolf’. The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek mesos (‘half’) and melas (‘black’), presumably referring to the blackish hairs, mixed with white hairs on the back.

Resting black-backed jackal, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lycaon pictus African hunting dog

This fascinating animal is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Hunting dogs – nomads of the savanna.

Hunting dogs are formidable hunters, with powerful jaws and long legs. They are able to run at 60 km/hour. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Vulpes vulpes Red fox

This fox is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Dog family.

Confiding red fox pup, Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cercopithecidae Old World monkeys

All species below are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes.

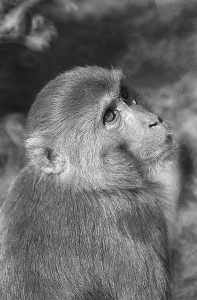

Macaca cyclopis Taiwan macaque

The fur of Taiwan macaque is pale grey with brownish here and there. These were photographed in the Bagua Shan Mountains, western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca fascicularis Long-tailed macaque

Long-tailed macaques, Wenara Wana Temple (popularly called ‘Monkey Forest’), Ubud, Bali, Indonesia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca mulatta Rhesus monkey

Rhesus monkey, photographed at the Buddhist temple Swayambhunath, Kathmandu, Nepal, where two troops of these monkeys live. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female rhesus monkey with a suckling young, Swayambhunath. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Macaca silenus Lion-tailed macaque

Male lion-tailed macaque, Puthutottam, West Ghats, Tamil Nadu, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papio anubis Olive baboon

Male olive baboon, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Papio cynocephalus Yellow baboon

Male yellow baboon, Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Piliocolobus kirkii Zanzibar red colobus

Zanzibar red colobus, photographed in Zanzibar. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Semnopithecus schistaceus Nepal langur, pale-armed langur

The Nepal langur is easily identified by its luxurious, pale grey fur and the large white ruff around its jet-black face. These two were photographed near Lake Dodi Tal, Asi Ganga Valley, Uttarakhand. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Theropithecus gelada Gelada baboon

In the Simien Mountains, the gelada baboon is fairly common in some areas. This picture shows a female at Gosh Meda. On the chest, males as well as females have a naked red skin patch, giving rise to an alternative name of the species, bleeding-heart monkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachypithecus auratus Javan lutung

Javan lutung, for sale at a market in the city of Yogyakarta, Java. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervidae Deer

A large number of deer species are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Deer.

Axis axis Spotted deer, chital

This beautiful deer is native to the Indian Subcontinent, including Sri Lanka, but is found nowhere else. It is fairly common in most of the distribution area, though declining in places due to habitat destruction. It has been introduced elsewhere, including Australia, United States, and several South American countries.

A medium-sized deer, males may weigh up to 100 kg, whereas the females are much lighter.

The generic and specific names are Latin, referring to an Indian animal, mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 A.D.). The Hindi name chital is derived from Sanskrit citrala (‘spotted’).

Spotted deer stag, drinking from a waterhole, Sariska National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Capreolus capreolus Roe deer

This small deer is distributed all over Europe, with the exception of Ireland and far northern Scandinavia, Finland, and Russia. It is also found in Turkey, the Caucasus, and northern Iran.

From Ukraine and the northern flanks of the Caucasus, eastwards through the taiga zone to the Pacific Ocean, and also in Tibet, Korea, and Manchuria, this species is replaced by the Siberian roe deer (C. pygargus). Formerly, these deer were regarded as a single species, but today most authorities recognize them as separate species. The Siberian roe deer is larger, with longer, more branched antlers than the European roe deer.

In Roman Latin, the term capra usually indicated a she-goat, but with the diminutive suffix olus added, it meant ‘a small deer’. The name pygargus stems from Ancient Greek pygargos, from pyge (‘rump’) and argos (‘white’), alluding to the deer flashing the white hair on the rump when alarmed.

Roe deer doe in the reddish summer coat, Møn, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus canadensis Wapiti, American elk

This is one of the largest deer species, stags weighing 320-330 kg, hinds 225-240 kg. It is also one of the largest mammals within its distribution area, which encompasses north-eastern Asia and North America. It has been introduced elsewhere, including Argentina and New Zealand.

To the early European explorers in North America, this animal resembled a moose (below), and, consequently, they gave it the name elk, which is the European English name for the moose, derived from Old Norse elgr. The name wapiti is a Shawnee and Cree word, meaning ‘white rump’. The Altai wapiti of Central Asia (C. c. sibiricus) is locally known as the Altai maral.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for deer.

Resting wapiti stag, Fort Niobrara Wildlife Refuge, Nebraska, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing wapiti hind, Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cervus unicolor Sambar deer

This very large deer, by some authorities named Rusa unicolor, has a wide distribution in Asia, from the entire Indian Subcontinent eastwards to southern China and Taiwan, and thence southwards through Indochina and Malaysia to Sumatra and Borneo.

The weight of a stag is typically around 350 kg, although large specimens may weigh as much as 550 kg. Hinds are smaller, weighing 100-200 kg. Populations of this deer have declined substantially in most areas, mainly due to hunting and habitat destruction. It has been introduced to various countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

The common name is derived from Sanskrit sambara (‘deer’).

In Maha Eliya Thenna National Park (Horton Plains), central Sri Lanka, sambar deer have become accustomed to tourists, as this one, which I could approach to within 10 metres. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a sambar hind, which is much bothered by flies, Ranthambhor National Park, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Odocoileus hemionus Mule deer, black-tailed deer

The genus Odocoileus only contains two medium-sized deer, native to the Americas. The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek odous (‘tooth’) and koilos (‘hollow’), alluding to the fact that these deer have hollow teeth.

The mule deer is widespread and rather common in the western half of North America, from southern Alaska southwards to Baja California and central Mexico.

The name mule deer refers to its rather large ears, reflected in the specific name, derived from Ancient Greek hemionos (‘mule’). The two common names indicate the main differences between this species and the widespread white-tailed deer (O. virginianus).

On a hot spring day, this mule deer hind is resting in the shade of a desert bush, Saguaro National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delphinidae Oceanic dolphins

This cosmopolitan family contains about 37 species, divided into about 18 genera.

Orcinus orca Killer whale, orca

This strikingly patterned dolphin is the largest member of the family, males reaching a length of more than 9 m and weighing up to 10 tons. Females are smaller, up to 7 m long and weighing 3-4 tons. It is the only member of the genus, found in all oceans of the world.

These animals are very intelligent and often perform in ocean parks.

The generic name is derived from the Latin Orcus (god of the underworld), and the suffix inus, thus ‘of the underworld’, or rather ‘of the realm of the dead’, like the common name alluding to these animals being efficient killers. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ferocious sea creature’.

Killer whale, Ocean Park, Hong Kong. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echimyidae Spiny rats

A large family with 27 genera and about 100 species, mainly found in South America, with some species in Central America and the Caribbean.

The family name is derived from Ancient Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’ or ‘sea urchin’) and mys (‘mouse’), alluding to the stiff hairs that many members of the family have on their body, presumably to deter enemies from eating them.

Myocastor coypus Nutria, coypu

This animal is native to the southern half of South America, living in wetlands. At an early stage, it was introduced to North America, Europe, and Japan for the fur trade. Over the years, numerous animals have escaped, and the species has become naturalized in many places. It is considered a pest, as it competes with, and sometimes expels, native species, erodes river banks, destroys irrigation channels, and chews up house panels etc.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek mys (‘mouse’) and kastor (‘beaver’), alluding to its resemblance to the beavers (Castor). The specific name is a Latinized version of the Spanish coipu, which is taken from koypu, the Mapudungun name of this animal.

Nutria, escaped on Avery Island, Louisiana, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elephantidae Elephants

Elephants and their sad fate are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Rise and fall of the mighty elephants.

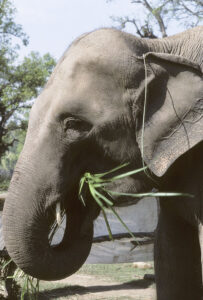

Elephas maximus Asian elephant

Grazing bull Asian elephant, Corbett National Park, Uttarakhand, India. Note that the gland in front of its ear is emitting fluid, indicating that it is in heat, called musht. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female Asian elephant in a breeding centre for elephants, near Sauraha, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Loxodonta africana African elephant

African elephant, eating grass, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. Note that it has only one tusk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

After spraying itself, this African elephant is covered in a layer of grey mud as a protection against biting insects, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Equidae Horses

The origin of horses, asses, and zebras is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Today, this formerly large family contains 7 species, all placed in the genus Equus. There are 3 species of zebra, living in Africa, 3 species af ass, living in Asia and Africa, and one species of horse, which went extinct in the wild, but has been reintroduced to Mongolia. Herds of feral domestic horses are found many places around the world.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for horses.

The 3 zebra species are described on the page Nature: Nature’s patterns.

Equus ferus ssp. caballus Domestic horse

In Europe, the true wild horse, or tarpan (Equus ferus ssp. ferus), was hunted to extinction, and the last one died in a Russian zoo in 1909. Another subspecies, Przewalski’s horse (E. ferus ssp. przewalskii), named after Russian geographer and explorer Nikolai Przewalski (1839-1888), only survived as scattered herds on the vast grass steppes in Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia. Attempts have been made to recreate the tarpan by crossing Przewalski’s horses with various ancient, primitive types of domestic horses, resulting in tarpan-like horses, such as the Konik horse. Today, herds of these ‘primitive’ horses have been released various places in Europe.

The domestication of wild horses is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘wild animal’, originally from Proto-Indo-European. The subspecific name is probably derived from Ancient Persian kaval, a term indicating a horse of inferior quality.

The Konik horse resembles the extinct tarpan, apart from the long mane. A feral population of these horses live in the nature reserve Oostvardersplassen, Flevoland, Holland, where this picture was taken. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As its name implies, the Belgian draft horse originates in Belgium. It is one of the strongest of the heavy horse breeds.

Portraits of Belgian horses, Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

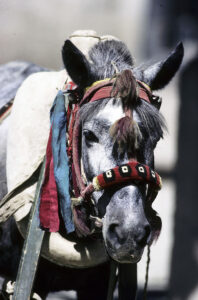

Tibetan horses are small and sturdy animals. This one was photographed in the town of Gyantse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A mule is a cross between a jack (male donkey) and a mare (female horse). – Shigatse, Tibet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Equus quagga Plains zebra

Resting plains zebra, subspecies chapmani, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Previously, plains zebras in Namibia were regarded as a distinct subspecies, antiquorum. However, recent studies have revealed that it is genetically identical to Burchell’s zebra, subspecies burchelli, which was once regarded as extinct. As subspecies burchelli was described prior to antiquorum, the former name takes precedence. Thus, the plains zebras of Namibia are now called Equus quagga ssp. burchelli. Following the extermination of the quagga, ssp. quagga, in the late 1800s, Burchell’s zebra is today the least striped surviving subspecies.

Burchell’s zebra, mare and foal, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Erithizontidae New World porcupines

These animals, comprising 19 species in 3 genera, are primarily South American, with a few species extending into Central America, and a single species in North America (below).

Erethizon dorsatum North American porcupine

This striking animal, whose body is covered in up to 30,000 quills, is the second-largest rodent in North America, only surpassed by the beaver (Castor canadensis). It grows up to 90 cm long, excluding the long tail, which may be to 30 cm long. It is quite heavy, usually weighing 7-10 kg, sometimes more.

Divided into 7 subspecies, it is distributed in most of subarctic Alaska and Canada, extending its range through western United States to the northernmost parts of Mexico, and in the eastern states it is mainly restricted to the Appalachian Mountains, southwards to Pennsylvania.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek erethizein (‘to irritate’), referring to the quills, the specific name from the Latin dorsatus (‘ridged’). Thus, the name can be loosely translated as ‘the animal with the irritating back’.

The word porcupine is derived from the Latin porcus (‘pig’) and spina (‘thorn’). Despite its name, this animal is not closely related to Old World porcupines (Hystrix).

An adult North American porcupine may have up to 30,000 quills. This one was observed at Bend, Oregon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Felidae Cats

This worldwide family, only absent from the Australian region, the polar areas, and Madagascar, is divided into two subfamilies, Felinae with about 32 largely smaller species, and Pantherinae with 7 mostly large species.

The lion (Panthera leo) is described below, whereas the snow leopard (P. uncia) is described on the page Animals: Animal tracks and traces. The sad fate of the tiger (P. tigris) is related on the page Folly of Man.

Acinonyx jubatus Cheetah

The fastest land mammal on Earth, during hunts often running at speeds of up to 64 km/h, being able to accelerate up to 112 km/h on short distances. Because of this ability, the cheetah was tamed as early as the 16th Century B.C. in Egypt, and later also in India, to be used for hunting.

This species mainly inhabits savanna, but is also found in various types of open forest. Four subspecies are currently recognized. The nominate jubatus occurs from Uganda and Kenya southwards through eastern and southern Africa to Namibia and South Africa. It has been exterminated in Zaire, Rwanda, and Burundi. The population is estimated at around 5,000 individuals.

Subspecies soemmeringii is restricted to north-eastern Africa, occurring in South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea.

With a total population estimated at less than 250 individuals, subspecies hecki is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. It has a scattered occurrence of tiny populations in southern Algeria, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Benin.

Today, the Asiatic cheetah, subspecies venaticus, is confined to Iran. It is classified as critically endangered by the IUCN, as the total population in 2017 was estimated at fewer than 50 individuals, scattered over the central plateau of Iran. In former times, this subspecies was distributed from the Arabian Peninsula and Turkey eastwards to Central Asia and India.

By 2016, the total cheetah population was estimated at around 7,100 individuals in the wild. Its decline is caused by loss of habitat, poaching for the illegal pet trade, and conflict with humans.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek akinitos (‘motionless’) and onyx (‘nail’ or ‘hoof’), thus ‘motionless nails’, referring to the fact that the cheetah, unlike other cats, is unable to retract its claws.

The specific name is derived from the Latin iuba (‘mane’ or ‘crest’) and atus (‘like’), thus ‘having a mane-like crest’, referring to the long mane of cheetah kittens below the age of 3 months. This mane is a means of camouflage, when the kittens are left in dense cover by their mother, when she goes hunting.

The name cheetah is derived from the Sanskrit citra, meaning ‘variegated’, ‘spotted’, or ‘speckled’.

Resting cheetah, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Felis catus Domestic cat

The domestic cat is described on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for cats.

Large kitten resting, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kittens, Funen, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Felis libyca African wildcat

Previously, this small cat was regarded as various subspecies of the European wildcat (F. silvestris), but today most authorities consider it a separate species. Despite its name, it is not only found in Africa. As of today, 3 subspecies are recognized, the nominate in northern Africa, cafra in southern Africa, and ornata in the Arabian Peninsula, the Middle East, north-western India, and Central Asia, eastwards to Mongolia and northern China.

Numerous other subspecies (or even species) have been described from skins that are now regarded as specimens of African wildcat.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘from Libya’. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

African wildcat, ssp. cafra, resting in savanna grass, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leopardus pardalis Ocelot

A medium-sized cat, which may grow to almost 1 m long and weighing up to 16 kg. It is distributed from extreme southern Arizona and Texas southwards through western and eastern Mexico and Central America to southern Peru and northern Argentina. Its prime habitat is in the vicinity of water, with dense vegetation cover.

Populations are decreasing in many parts of its range due to habitat destruction, hunting, and traffic accidents.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek leon (‘lion’), and the Latin pardus (‘mottled’), originally from Ancient Greek pardos (‘leopard’), thus ‘the mottled lion’, or ‘lion-leopard’. Strange names for this smallish cat!

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘mottled like (a leopard)’.

Female ocelot in captivity, Tucson Desert Zoo, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Panthera leo Lion

Lions live in prides, consisting of females and young, and a single or several males. If there is more than one male, they are brothers or half-brothers. Even if they often don’t participate in a hunt, the stronger males will chase away lionesses and cubs from a prey, if it is not large enough to feed the entire pride.

The lion is unique among cats due to the male’s mane, a large growth of hair around the neck and down the chest, and often a little way down the back. The mane makes a male lion look larger than he actually is, without the disadvantage of a larger weight, which would require more food. A large mane is a signal to other males that here comes a powerful animal that shouldn’t be challenged, even if the challenging male is in fact larger than his opponent, but has a smaller mane. The mane also gives some protection during fights among males, for instance when stray males attempt to take over a pride.

The lion is described in depth on the page Animals – Mammals: Lion – king of the savanna, and an unusual nightly encounter with lions is related on the page Travel episodes – Tanzania 1990: Lions in the camp.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek panther, a term relating to almost black leopards, in English also known as panthers. The specific name is a Latinized version of the classical Greek name of the lion, leon.

Male lion, resting among grass, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This male in Serengeti National Park has a huge mane. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Panthera pardus Leopard

This large cat has a very wide distribution, from Ussuriland in south-eastern Russia southwards through parts of China and Southeast Asia to Indonesia, and thence westwards through the Indian Subcontinent to the Middle East, and most of sub-Saharan Africa. It has adapted to a huge variety of habitats, from tropical jungles to semi-desert and mountains, and even farmland near villages.

More about leopards, including a terrible man-eater from northern India, is found on the page Animals – Mammals: The spotted killer.

The specific name is explained above at Leopardus.

Leopard, Chief’s Island, Okawango, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leopard, dozing in a tree, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This leopard is resting after filling its stomach to the bursting point with meat from a white-bearded wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi), Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Giraffidae Giraffe and okapi

This family consists of only two surviving species, the giraffe (below), and the okapi (Okapia johnstoni), which is restricted to eastern Zaire.

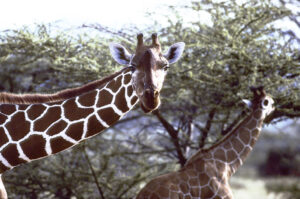

Giraffa camelopardalis Giraffe

The tall and seemingly ungainly giraffe was once distributed throughout Africa, except in rainforest. However, it has diminished alarmingly, and today there may be less than 100,000 individuals.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only one species of giraffe exists, divided into 9 subspecies, whereas other authorities recognize up to 8 separate species.

The generic name is derived from Arabic zarafah, meaning ‘the one that walks fast’, whereas the specific name is derived from Ancient Greek kamelos (‘camel’) and pardos (‘leopard’), and the Latin alis (‘resembling’), alluding to its camel-like shape and leopard-like pattern.

Other pictures, depicting giraffes, are shown on the page Nature: Nature’s patterns.

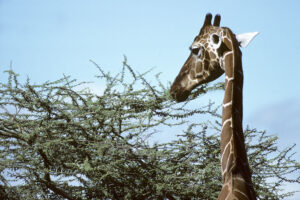

The reticulated giraffe, subspecies reticulata, is distributed in extreme southern Ethiopia, north-eastern Kenya, and south-western Somalia.

Reticulated giraffes, Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Kordofan giraffe, subspecies antiquorum, is found in southern Chad, the Central African Republic, northern Cameroun, and north-eastern Zaire. The pattern somewhat resembles that of the reticulated giraffe, but is much paler. Formerly, it was believed that populations in Cameroun belonged to subspecies peralta, but genetic research has shown that this is incorrect. It is highly endangered, as only about 400 individuals survive in fragmented populations.

Kordofan giraffe, Waza National Park, Cameroun. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

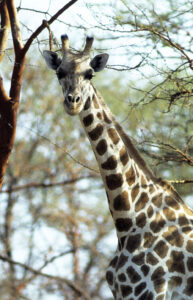

The dark blotches on the Masai giraffe, subspecies tippelskirchi, have a jagged outline. It is distributed in Tanzania and extreme southern Kenya.

Masai giraffe, Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Masai giraffe, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

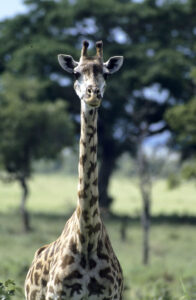

The giraffes in Arusha National Park, northern Tanzania, are probably Masai giraffes, although some authorities regard them as hybrids between reticulated giraffe and Masai giraffe, called Galana giraffes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Angolan giraffe, subspecies angolensis, is found in south-western Zambia, central Botswana, Zimbabwe, and northern Namibia.

Angolan giraffe, feeding on acacia leaves, Chief’s Island, Okawango, Botswana. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Angolan giraffes, Chief’s Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hippopotamidae Hippos

A small family of only two surviving species. The hippo (below) and its smaller cousin, the pygmy hippo (Choeropsis liberiensis), are both described on the page Animals – Mammals: Hippo – the river horse that lives on both sides.

Hippopotamus amphibius Hippo

Hippos can crush a canoe with a single bite from their enormous jaws. – Ngorongoro Crater (top), and Banagi River, Serengeti National Park, both in Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hominidae Man and apes

Previously, apes (orangutans, gorillas, and chimpanzees) were placed in the family Pongidae.

Pongo Orangutans

Formerly, orangutans were regarded as a single species, Pongo pygmaeus, which was confined to rainforests of Sumatra and Borneo. Lately, however, it has been split into three separate species. The Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), comprising 3 subspecies, is still widespread in Borneo, whereas the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii) is restricted to northern Sumatra, primarily the Aceh Province. The Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), which lives in an area of just 1,500 km2 in Batang Toru, south of Lake Toba, Sumatra, was described as a distinct species as late as 2017. They all live in lowland rainforest, rarely found above 500 m altitude, the Sumatran orangutan occasionally up to c. 1,500 m.

All three species are seriously endangered due to habitat destruction and fragmentation, and illegal poaching for zoos. It has been estimated that the population of the Bornean orangutan in 1973 was about 300,000 individuals, and it is assumed that this number will decline to c. 50,000 by 2025. The Sumatran orangutan has an estimated population of fewer than 14,000, and it is predicted that this number will decline by 80% by 2060. The population of Tapanuli orangutan is fewer than 800, and this number is still decreasing.

The generic name is derived from mpongi, a term that the Kongo (a Bantu people) used for the gorilla. However, in the 18th Century the terms orangutan and pongo were used for all great apes, and French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède (1756-1825) applied the name Pongo to orangutans in 1799.

Pongo pygmaeus Bornean orangutan

In 1985, I visited the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre in Sabah, Borneo. This centre is home to a number of orphaned orangutans, which were confiscated from poachers, who shot their mothers to get hold of the young. This centre, where the young ones are trained to a life in the wild, is presented in depth on the page Travel episodes – Borneo 1985: Visiting orangutans.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘dwarf’ or ‘of short stature’. Perhaps the name indicates that the orangutan seems short because of its curved stature when walking.

An adult male, living in a semi-wild state near the centre. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lacking a mother, the orphaned young often become much attached to one another. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hyaenidae Hyaenas

About 5 million years ago, this family was much larger, containing at least 21 genera with more than 50 species, widely distributed in Eurasia, Africa, and North America. Today, only 4 species remain: spotted hyaena (below), striped hyaena (Hyaena hyaena), brown hyaena (Parahyaena brunnea), and aardwolf (Proteles cristatus). They are restricted to Africa, with the exception of the striped hyaena, which is also found in the Middle East and India.

Crocuta crocuta Spotted hyaena

This powerful carnivore is found in most of sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of deserts, rainforests, and alpine areas on mountain tops. It once ranged all over Europe and northern Asia, from Spain and France eastwards to eastern Siberia. It is still not clear why it went extinct in Siberia, but its disappearance from Europe is linked to the decline in grasslands – its favoured habitat – about 12,500 years ago.

The spotted hyaena has a very complex social behaviour, with respect to group-size, hierarchical structure, and frequency of social interaction among both kin and unrelated group-mates. However, their social system is openly competitive rather than cooperative, with access to kills, mating opportunities, and the time of dispersal for males, all depending on the ability to dominate other clan-members. (Source: Holekamp, Sakai & Lundrigan, 2007. Social intelligence in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, 362, pp. 523-538)

The generic and specific names are derived from Ancient Greek krokottas, first mentioned by Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian Strabo (c. 63 B.C. – c. 24 A.D.) in his Geographica, where the animal is described as a mix of wolf and dog, native to Ethiopia.

Resting spotted hyaena, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leporidae Hares and rabbits

This family contains more than 60 species, of which about 32 belong to the genus Lepus (true hares). Members are found on all continents, except Antarctica, although they have been introduced to Australia.

The family name means ‘those that resemble lepus’, lepus being the classical Latin word for hare.

Lepus europaeus European hare

This species is native to the major part of Europe and the Middle East, and thence eastwards across the Asian steppes to Mongolia. It has also been introduced elsewhere, including Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and southern South America.

European hare, resting in a littoral meadow, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oryctolagus cuniculus European rabbit

Originally, this species was native to south-western Europe and north-western Africa, but has been introduced to many other areas as a hunting object. It was first brought to Britain by the Romans, following their invasion in A.D. 43, and today it is extremely common – an estimate in 2004 suggested about 40 million.

In Australia, 24 European rabbits were introduced in Victoria in 1859. The vast farmlands were an ideal habitat for the rabbits, and the mild winters allowed them to breed year-round, so they quickly spread over most of the country. Australia’s equivalent to the rabbit, the greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis), could not compete with the fast-breeding rabbits, and today it is an endangered species.

Other places of introduction include New Zealand, certain Hawaiian islands, and islands off the coast of South Africa. There are also many instances of pet rabbits, which have escaped, forming feral populations.

In countless cases, this species has done severe damage to the environment, partly through overgrazing, partly through its system of underground tunnels, and partly through competition with local wildlife. It is regarded as an invasive species in most countries.

In 1972, English author Richard Adams (1920-2016) wrote a novel, Watership Down, describing the life of a group of wild rabbits in southern England. Although the rabbits have been anthropomorphized, the story gives a fair account of the life of these animals.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oryktos (‘dug up’) and lagos (‘hare’), thus ‘the digging hare’. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘burrow’, but was also the classical Latin word for rabbits.

The European rabbit was introduced to Britain almost 2,000 years ago, and today it is extremely common. This one is sitting outside its den in Spey Valley, Scotland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lorisidae Lorises, pottos, and angwantibos

This family of small, nocturnal primates contain 5 genera with about 16 species, living in South and Southeast Asia, and in Africa south of the Sahara.

Nycticebus menagensis Philippine slow loris

This species, which was previously regarded as a subspecies of the Sunda slow loris (N. cougang), is native to northern and eastern Borneo, and the Sulu Archipelago in the Philippines. It is nocturnal and arboreal, living in evergreen forests.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek nyktos (‘night’) and kebos (‘monkey’). The meaning of the specific name is not known.

This Philippine slow loris had been injured and was now recovering in Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, Sabah, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ochotonidae Pikas, mouse-hares

These small animals, comprising about 30 species, are all placed in a single genus, Ochotona. With the exception of two species in North America, they all occur in the eastern half of subarctic and temperate Asia. Despite their rodent-like appearance, their nearest relatives are rabbits and hares.

They mainly live in rocky or grassy ares, where they either dig a burrow or live in crevices among rocks and scree. During the summer months, pikas collect large amounts of grass and other plants to store as winter food, as they do not hibernate.

The generic name is probably derived from the Mongolian word for these animals, ogdoi, whereas the name pika is derived from their Tungus name, piika.

Ochotona roylei Royle’s pika

This species is the commonest and most widespread Himalayan pika, distributed from Kashmir eastwards to northern Myanmar and the Yunnan and Sichuan Provinces. Like the previous species, it arranges its nest among boulders, but generally lives at lower altitudes in forested areas.

The specific name was given in honour of British surgeon and naturalist John Forbes Royle (1798-1858), who is chiefly known for his works Illustrations of the Botany and other branches of Natural History of the Himalayan Mountains, and Flora of Cashmere.

This Royle’s pika, encountered at Phedi, near Gosainkund, Langtang National Park, central Nepal, was remarkably confiding, scurrying about between our feet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Otariidae Eared seals

As their name implies, these seals have a small ear flap, which distinguishes them from the true seals, family Phocidae, and the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus). Eared seals include sea lions and fur seals, altogether 7 genera with 15 species, occurring throughout the Pacific Ocean and the southern parts of the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. They are absent from the north Atlantic.

Arctocephalus pusillus Brown fur seal

There are two widely separated populations of this seal, also known as Afro-Australian fur seal: the South African, or Cape, fur seal, subspecies pusillus, and the Australian fur seal, subspecies doriferus.

The Cape fur seal ranges along the southern coasts of Africa, from Ilha dos Tigres in southern Angola, along the Namibian coast to Algoa Bay in South Africa, whereas the Australian subspecies lives in south-eastern Australian waters, along the coasts of Tasmania, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia, with the largest concentration in the Bass Strait.

The preferred breeding habitats of these seals are rocky islands, or pebble or boulder beaches. The population of the Cape fur seal is approximately 2 million, whereas that of the Australian fur seal is around 120,000. (Source: iucnredlist.org/details/2060/0)

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arktos (‘bear’) and kephale (‘head’), thus ‘with a bear-like head’. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘very small’ – not a very appropriate name, as the animal is not particularly small, but maybe it is smaller than other eared seals.

Bull Cape fur seal, surrounded by females and pups, Cape Cross, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sleeping female Cape fur seal, Cape Cross, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eumetopias jubatus Northern sea lion

This animal, also known as Steller’s sea lion, lives in the northern Pacific, from the Kuril Islands in Russia to the Gulf of Alaska in the north, and thence southwards to central California. It is the largest of the eared seals (Otariidae) and the sole member of the genus Eumetopias.

The name Steller’s sea lion commemorates German naturalist, physician, and explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709-1746), who described the species in 1741. He participated in the Second Russian Kamchatka Expedition, led by Danish explorer Vitus Bering (1681-1741).

The generic name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘having a broad forehead’, whereas the specific name is Latin, meaning ‘having a mane’.

Female northern sea lion, Oregon, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procaviidae Hyraxes

Hyraxes constitute two genera, Procavia and Dendrohyrax, in Procaviidae, the only living family within the order Hyracoidea. These animals resemble large guinea pigs, but their nearest living relatives are in fact elephants.

Dendrohyrax arboreus Southern tree hyrax

The 3 species of tree hyraxes, genus Dendrohyrax, are distributed in sub-Saharan Africa. The southern tree hyrax is found from eastern Zaire, southern Uganda, and southern Kenya southwards to eastern Angola, Zambia, and northern Mozambique, with two isolated populations in southern Mozambique and south-eastern South Africa. This animal lives in various types of forest, and also in savanna and rocky areas, provided there are trees. It may be encountered from the lowlands up to an elevation of 4,500 m.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’) and hyrax (‘shrew-mouse’), the last part alluding to the rodent-like appearance of these animals. The specific name is derived from the Latin arbor (‘tree’), and the suffix eus, thus ‘living in trees’.

Southern tree hyrax, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procavia capensis Rock hyrax

Divided into at least 5 subspecies, this animal is distributed in most of northern Africa, from southern Algeria, southern Libya, and the Nile Valley southwards to Zaire and northern Tanzania, in the Arabian Peninsula, and in southern Africa. In South Africa, it is known as dassie. It lives in rocky areas, from sea level up to elevations around 4,200 m. Where it is regularly fed, it can become very tame.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek pro (‘before’), or rather from pros (‘towards’ = ‘resembling’), and çavia, the obsolete Portuguese name of the Brazilian spiny rat (Makalata didelphoides) of the family Echimyidae, derived from the Tupi name of this animal, saujá. In classical Latin, presumably due to a misunderstanding, the word cavia was used for the guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), thus the name can be rendered as ‘resembling guinea pigs’.

The specific name refers to the Cape Province of South Africa. Presumably, the type specimen was collected there.

Black-necked rock hyrax, subspecies johnstoni, scratching, Gorges Valley, altitude about 4,000 m, Mount Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhinocerotidae Rhinos

A small family of 5 species in 4 genera, distributed in eastern and southern Africa, northern India, southern Nepal, Indochina, and Indonesia.

Rhino parts have been used as ingredients in traditional Asian medicine for at least 2000 years. Virtually every part of the animal is used: the horn for reducing fever and spasms; the skin for skin diseases; the penis as an aphrodisiac; the bones to treat bone disorders; the blood “as a tonic for women who are suffering from menstrual problems.”

In China, powdered horn is regarded as an aphrodisiac. However, chemical analyses have not revealed any active ingredients to suggest that the remedy could be effective in this respect. (Source: J. Still 2003. Use of animal products in traditional Chinese medicine. In: Complementary Therapies in Medicine)

In fact, western medical experts tend to discount all claims of any curative power in rhino horn. It is well known that aspirin contains similar properties and produces many of the same results as rhino prescriptions in patients.

Formerly, rhino horn was used for adorning dagger sheaths in Yemen – a practice which may still take place.

All five species of rhino are critically endangered due to widespread poaching, the Asian species also due to habitat loss.

Ceratotherium simum White rhinoceros, square-lipped rhinoceros

This is the largest living species of rhino, growing to 4 m long and weighing up to 2.3 tonnes. Females live in small herds, as opposed to other rhinos, which are largely solitary. There are two subspecies, the southern nominate race, which counts about 20,000 individuals, and the northern, subspecies cottoni, which has gone extinct in the wild due to poaching. Only two animals survive in captivity.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek keras (‘horn’) and therion (‘beast’), the specific name from Ancient Greek simos (‘snub-nosed’), alluding to the square mouth of this species, an adaptation for grazing.

It has often been claimed that the most commonly used name, white rhino, is a mistranslation of the Dutch word wijd to the English word white. Wijd means ‘wide’ in English, and it was supposed to refer to the width of the rhinoceros’s mouth. However, this is not the case. In fact, the name white rhino can be traced back to a letter in Dutch, written by the Boer Petrus Borcherds to his father in 1802. In this letter, he mentions two rhinos, both killed in 1801, a male of the ‘black variety’, and a female ‘white’ rhino. Concerning the female, Borcherds stated (still in Dutch): “She was of the type known to us as the white rhinoceros. (…) I expected this animal to be entirely white, according to its name, but found that she was a paler ash-grey than the black male.” (Source: Jim Feely 2007. Black rhino, white rhino: what’s in a name? Pachyderm 43, pp. 111-115)

However, both species are in reality grey, the ‘black’ rhino somewhat darker than the ‘white’ rhino.

White rhino, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe, wearing a radio collar for easy tracking. Its horn was removed to deter poachers from killing it, but has started growing out again. The number of rhinos in Zimbabwe has plummeted in later years due to poaching, and the present population is only 7-800 individuals. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Diceros bicornis Black rhinoceros, hook-lipped rhinoceros

In former days, this rhino was abundant in sub-Saharan Africa, divided into 7 or 8 subspecies. However, due to poaching it has largely disappeared, today surviving in small populations in reserves in Kenya, Tanzania, and southern African countries.

Both scientific names mean ‘two-horned’, the generic name derived from Ancient Greek dyo (‘two’) and keras (‘horn’), the specific name from the Latin bis (‘twice’) and cornu (‘horned’). The common name is explained above (see white rhino).

Resting black rhinos, Ngorongoro Crater. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rhinoceros unicornis Indian rhinoceros, greater one-horned rhinoceros

Formerly, this animal was widespread and common in grasslands of northern India and southern Nepal, but today only about 3,500 survive in small pockets, with about 70% of the entire population in Kaziranga National Park, Assam.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek rhinos (‘nose’) and keras (‘horn’), the specific name from the Latin unus (‘one’) and cornu (‘horned’).

Indian rhino, Kaziranga National Park, Assam, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Indian rhino is enjoying a mudbath, near Sauraha, southern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sciuridae Squirrels

A large family of rodents, comprising about 60 genera and c. 300 species worldwide. These animals are found on all continents, except Antarctica. In Australia, however, they have been introduced by humans.

Numerous members of the family are described on the page Animals – Mammals: Squirrels.

The word squirrel, which was in use as early as 1327, is derived from the Anglo-Norman name esquirel, which is again from the Old French escurel, a corruption of the Latin sciurus, which is derived from Ancient Greek skiuros, ultimately from skia (‘shadow’) and oura (‘tail’), thus ‘shadow-tailed’, alluding to the large, bushy tail of many squirrels. Some species have a habit of flicking their tail over their back, and in this way tropical species are able to use their tail as a protection against the fierce sunshine.

Callosciurus

This genus contains about 15 species, found mainly in Southeast Asia, with a few species occurring in Nepal, northeastern India, Bangladesh, southern China, and Taiwan. Most species live in tropical rain forests, but some have adapted to a life in city parks and gardens. Their food consists of nuts, fruits, and seeds, and also insects and bird eggs.

The first part of the generic name is derived from Ancient Greek kallos (‘beautiful’) – although many of the species are of a rather plain brown colour. The last part is explained above.

Callosciurus erythraeus Red-bellied squirrel, Pallas’s squirrel

Despite its name, this species does not always have a red belly. It is widespread, found from eastern Nepal, Bhutan, and north-eastern India eastwards to Southeast Asia, southern China, and Taiwan. More than 30 subspecies have been described, although not all are recognized by many authorities.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek erythros (‘red’) and the suffix eus, thus ‘reddish’, alluding to the species most often having a reddish belly.

Subspecies taiwanensis of the red-bellied squirrel is common and widespread at lower elevations in Taiwan. This one was feeding on bird food near a temple, dedicated to Confucius, in Tainan, southern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Marmota Marmots

Marmots are large, ground-living squirrels, comprising 15 species, which occur in Europe, Asia, and North America. They are the largest and fattest of squirrels, growing up to 60 cm long and weighing up to 7 kg.

Marmots live in burrows up to 2 m underground, digging tunnels up to 10 m long. They often sit on their haunches outside their burrow, and their shrill warning whistles can be heard far away. Marmots are almost exclusively vegetarians. They do not make food deposits, but in autumn they have become extremely fat, and hibernate throughout the winter.

The generic name is a corruption of the Latin muris montanus (‘mountain mouse’).

Marmota marmota Alpine marmot

This is a common animal, living in alpine areas at elevations between 800 and 3,200 m, in southern France, the Vosges, the Black Forest, the Alps, the northern Apennines, the Carpathians in Romania, and the Tatras in Poland. In 1948, it was reintroduced with success in the Pyrenees, where it had disappeared at end of the last Ice Age.

Alpine marmot outside its den, Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ratufa Oriental giant squirrels

A genus with 4 species of large squirrels, distributed from India and Sri Lanka eastwards to Southeast Asia and southern China, and thence southwards to Indonesia.

The generic name is unexplained.

Ratufa indica Indian giant squirrel, Malabar giant squirrel

This species is endemic to India, mainly found in forests and woodlands in hilly areas. It is strictly arboreal, and most of its food consists of leaves, fruits, and seeds.

Indian giant squirrel, feeding on pulp of a species of breadfruit, Artocarpus hirsutus, Periyar National Park, Kerala, South India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Suidae Pigs

Members of this family, counting 6 genera with 18 or 19 species, are native to Europe, Asia, and Africa. New World pigs, called peccaries or javelinas, belong to a different family, Tayassuidae.

Sus (scrofa) domesticus Domestic pig

Some authorities recognize the domestic pig as a separate species, others regard it as a subspecies of the wild boar (Sus scrofa). The domestic pig is described in depth on the page Animals: Animals as servants of Man.

Free-running pigs, Fur, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Free-running pigs, wallowing in mud, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phacochoerus africanus Common warthog

Previously, this animal was thought to be the only member of the subfamily Phacochoerinae, under the name P. aethiopicus, but recently it has been split into two species, the desert warthog, named P. aethiopicus, which lives in arid areas of northern Kenya, Somalia, and eastern Ethiopia, and the widespread common warthog, named P. africanus, which lives in grassland and woodland in most of sub-Saharan Africa, only avoiding deserts and rainforest.

From a distance, this animal appears largely naked, seemingly only with a crest along the back, and tufts of hair on the cheeks and tail. At close quarters, however, you notice a cover of short, bristly hairs on the body. The name warthog refers to the facial wattles, larger in the males, which also have prominent tusks that may sometimes reach a length of up to 60 cm, much smaller in the females.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phakos (‘wart’) and khoiros (‘pig’).

Male common warthog with huge tusks and prominent wattles, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female common warthog with very small tusks and almost no wattles, Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ursidae Bears

There are altogether 8 species of bears, widely distributed in Eurasia and North America, and a single species, the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), in the Andes of South America.

Due to illegal hunting, and to feed the insatiable Asian markets for traditional medicine and bear paw soup, bears have disappeared, or become very rare, in many areas, including Europe, Southeast Asia, Korea, China, and Taiwan. Today, five species are endangered.

Ursus thibetanus Asian black bear, moon bear

This bear is distributed at scattered locations, from south-eastern Iran eastwards across the Himalaya and Indochina to China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and south-eastern Siberia (Ussuriland). Previously, it was found in a much larger area, but has declined drastically.

Many Asian black bears are kept in captivity to supply the markets for traditional medicine and bear paw soup. In South Korea, for instance, only around ten individuals live in the wild, whereas about 1,600 are kept in captivity, often under horrible conditions. These captive bears are often killed in the most cruel and horrendous ways, and that this practice is illegal does not seem to deter consumers.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for bears. The specific name means ‘from Tibet’.

Asian black bear, photographed in Chengdu Zoo, Sichuan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Birds

Accipitridae Eagles, hawks, and allies

Gyps bengalensis Indian white-rumped vulture

This bird was once abundant in the Indian Subcontinent, but during the last 30 years or so, most populations of this species, and other vultures, have diminished alarmingly due to poisoning from diclofenac, a veterinary drug widely used to treat diseases in livestock. Research has shown that when these vultures feed on cattle carcasses, diclofenac causes kidney failure.

Today, it is critically endangered, and maybe as few as 6,000 individuals exist in the wild.

The generic name is the classical Greek term for vultures. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of Bengal’. Strictly speaking, Bengal is the lowland around the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, but in 1788, when German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin (1748-1804) described the bird, the term ‘Bengal’ indicated a much larger portion of northern India.

This Indian white-rumped vulture is being teased by a house crow (Corvus splendens), which is pulling its feathers, Jaisalmer, Rajasthan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Haliaeetus vocifer African fish-eagle

This iconic bird is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, always near water. It has been declining in later years, probably due to widespread usage of pesticides.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek hali (‘of the sea’) and aetos (‘eagle’). Despite the name ‘sea-eagle’, many of the species are living at freshwater areas inland. These species are termed ‘fish-eagles’.

This species was described by French naturalist François Levaillant (1753-1824), who named it vocifer (’the one who has a penetrating voice’) – a most suitable name for this eagle, whose scream is often resounding over the African landscape. It is the national bird of no less than three countries: Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Sudan.

This African fish-eagle, observed at the Rufiji River, Tanzania, was indeed confiding. Our rubber dinghy bumped into the tree, in which it was resting, but it merely glanced down at us and didn’t take off. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alaudidae Larks

A family with 21 genera and about 100 species, distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species reaching the Americas, and Australia, respectively.

Alauda arvensis Skylark

This bird breeds in a vast area, from the entire Europe eastwards to Kamchatka, Korea, and Japan, southwards to northern Africa, Turkey, northern Iran, Mongolia, and northern China. Northern populations are migratory, wintering as far south as northern Africa, Arabia, Pakistan, and southern China.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for lark. The specific name is derived from the Latin arvus (‘cultivated’), alluding to the skylark being common in cultivated areas.

This exhausted skylark was found in Nature Reserve Tipperne, Ringkøbing Fjord; Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alcedinidae Kingfishers

Kingfishers, comprising about 114 species of small to medium-sized, often brilliantly coloured birds, are characterized by having a large head, a long, sharp, pointed bill, and very short legs. As their name implies, most of these birds eat fish, although many species live away from water, eating mainly small invertebrates.

These birds are divided into 3 subfamilies: river kingfishers (Alcedininae), tree kingfishers (Halcyoninae), and water kingfishers (Cerylinae).

Halcyon

A genus of 11 medium-sized kingfishers, distributed in warmer areas of Africa and Asia.

The generic name is associated with a bird of Greek legend, called Halcyon, generally thought to be the common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis). The Ancients believed that this bird made a floating nest in the Aegean Sea and had the power to calm the waves while brooding her eggs. Two weeks of calm weather were to be expected when the Halcyon was nesting, which took place around winter solstice. These Halcyon days were generally regarded as beginning on the 14th or 15th of December.

This belief in the bird’s power to calm the sea originated in a myth recorded by Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 B.C. – c. 17 A.D.), known as Ovid. The story goes that Aeolus, ruler of the winds, had a daughter named Alcyone, who was married to Ceyx, the king of Thessaly. Ceyx drowned at sea, and in her grief, Alcyone threw herself into the waves. However, instead of drowning, she was transformed into a bird and carried to her husband by the wind. (Source: phrases.org.uk)

Halcyon albiventris Brown-hooded kingfisher

This bird is very widely distributed in Sub-Saharan Africa, from Congo eastwards to southern Somalia and thence southwards to Namibia and South Africa. It lives in woodland, shrubberies, grasslands with trees, parks, and gardens, and may also be observed in cultivated areas. It occurs from the lowland up to an elevation of about 1,800 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin albus (‘white’) and venter (‘belly’).

Brown-hooded kingfisher, Msumbugwe Forest, northern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Halcyon leucocephala Grey-headed kingfisher

A bird of various types of forest, especially riverine woodland. Nests have been found in riverbanks. It is quite common south of the Sahara, from Mauritania and Senegal eastwards to Ethiopia and Somalia, and thence southwards to South Africa, although absent from the southernmost part. It is also found on the Cape Verde Islands and in southern Arabia.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leukos (‘white’) and kephale (‘head’), although the head is grey rather than white.

Grey-headed kingfisher, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ispidina

This genus contains only 2 African species, closely related to members of the genus Corythornis.

The generic name is derived from the Latin hispida (‘kingfisher’), and the suffix ina, denoting something small.

Ispidina picta African pygmy kingfisher

This tiny kingfisher is widespread in forested areas south of the Sahara, being absent from the Somali Desert and large parts of south-western Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘painted’, alluding to the colourful plumage of this bird.

African pygmy kingfisher, Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Anatidae Ducks, geese, and swans

At present, this large family contains 43 genera with about 146 species, distributed almost worldwide.

Anas

Following genetic studies, this formerly very large genus has been divided into 7 genera, with 31 species remaining in Anas.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for duck.

Anas platyrhynchos Mallard

A very widely distributed species, found across subarctic, temperate, and subtropical areas of North America and Eurasia, southwards to Mexico, Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, and China. It has also been introduced to many other places as a hunting object, including South America, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa.

The drake is a gorgeous bird in breeding plumage, with grey sides, purple breast, and glossy-green head, with a blue shine from certain angles. A picture of the female, which is a uniform speckled brown, is shown on the page Animals – Animals as servants of Man: Poultry.