Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

A life of travelling

From a very young age, I have had a great interest in animals, in the beginning centered around dogs and cats. My parents later told me that once we were out driving, I suddenly shouted: ”I want to see dogs!”

I pestered my parents to have a puppy, but my father, very wisely, objected to that idea. He probably knew who was going to take care of the dog when it had lost its initial charm. Instead, I focused my interest on birds – an interest I have had ever since. Besides the common blackbirds and house sparrows around our house, my first recollection of a bird is a jay – a beauty in reddish plumage, having a black moustachial stripe and a fantastic blue and white patch on the forewing. From that day, I was hooked.

In my school, our grade had a brilliant biology teacher, Wagner Nielsen, who managed to catch our interest. One day, I think it was in 7th grade, he suggested that all of us, on the following Sunday (which was our only day off), should make a trip on bicycles to a wetland about 20 km away. Everybody agreed to this idea. ”Remember rubber boots!” he said.

As the trip was going to start at 4 A.M., I expected some, especially among the girls, to stay away, but everybody showed up! A couple of the girls were wearing shoes. Wagner, as we called him, just laughed and said that they would surely get their feet wet. Off we went on our long trip, and everybody endured. On this trip, I and two of my class mates, Peter and Bent, became interested in birds in earnest, and in the following years we often went birding together.

Peter was acquainted with another birdwatcher one grade above us, Torben Hviid Nielsen, who introduced us to a local club for young people with an interest in nature. Here, we met a lot of like-minded youngsters, many of whom are still my friends today. We investigated areas for birds, mammals, plants etc., and we went on day-long excursions in a rented bus to see new areas, which were unfamiliar to us, such as moors and raised bogs.

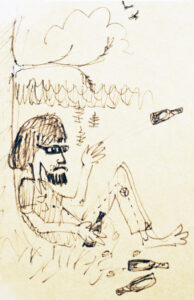

My photographic ‘career’ started relatively late. I was 17 years old, before I bought my first camera, of the brand Exa IIa, an excellent German-made camera. (I couldn’t afford high-quality cameras, such as Leica).

In the beginning, my pictures were of poor quality, but as time went by I began to notice, how important the balance between light and dark in a picture was. I also noticed that withered grass stems were extremely disturbing elements in plant pictures, especially if they were slanting behind the plant you wanted to photograph. I also learned that when taking pictures of low plants you would get the best result by kneeling or lying down to the same level as the plant.

As opposed to plants, animals are mobile, so you rarely have time to play with the composition of the pictures, but just click away when the chance occurs.

I dare propose the allegation that photography is an art on par with painting, drawing, and production of sculptures and ceramics. Naturally, I am not talking about the ubiquitous snapping of selfies etc., but about ‘drawing with light’, i.e. playing with composition and the balance between light and dark in a picture (see examples on pages Shadows and Silhouettes).

As it turned out, two of the books I bought were going to influence my life tremendously. One, called Bøj dig for Shiva (’Bow to Shiva’), was written by a Dane, Sten Kjærulff Nielsen, who described a long journey he made 1960-1961 to the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia. Nielsen’s trip was very cheap indeed, as he hitch-hiked most of the way, living as simple as possible.

In his foreword, the following passage appealed a great deal to me: ”If you don’t ask anything of your life, but keep to the bottom, you’ll always manage, and be happy, too. Not so many people are happy. The Indians have something they call ’the sacred indifference’: What is all this nonsense to me. It’s just Maya, just bluff and smoke. Future career, your place in The Machine, and all that.”

After high school I joined university to study anthropology, but soon got the impression that foreign peoples were made into simple study objects. I felt exactly like Nielsen. Instead of grouping peoples into academic systems of society and kinship, or describing their way of life in a dry and scientific form, I would much rather go out there to meet them at their own level, without any thoughts of a future academic career, or of publishing peer-reviewed papers. Consequently, I gave up studying anthropology.

Thesiger’s stay in Iraq ended abruptly in 1958, when a revolution took place in the country. The Iraqi royal family was murdered, and all British citizens were told to leave immediately. Iraq was declared a socialist republic, its new government being on friendly terms with the Soviet Union. After a number of chaotic years, Iraq became a relatively stable and safe place, where tourists were, if not exactly made welcome, then at least accepted.

I felt that these swamps were an area within my economic possibilities. What if I found a fellow traveller, and we bought a second-hand car, maybe we could drive to Iraq?

However, before this could take place, I had to do 16 months of civil work for the government, instead of military service. One evening, in a work camp, I was playing billiard, when another civil worker, whom I hadn’t met before, approached me, saying:

”Are you the one watching birds?”

“Yes.”

”And you have planned to go to Iraq by car?”

“Yes.”

”Can I join you?”

In this way, I was acquainted with Arne Koch Christoffersen, a fellow birdwatcher, and by profession a mechanic, which was highly convenient, as I had planned to go to the Middle East by car, and my mechanical knowledge was next to nil.

Together, we made plans for our trip. In 1972, we bought a second-hand Volkswagen van, constructed sleeping berths in the back, bought a gas stove, put clothes and several books into a few old wooden beer crates – and off we went. We were very young and very inexperienced travellers, ignorant of red tape. Just before leaving, we learned that we would need a carnet de passage, a document which ensures that when you bring a foreign car into a country you also export it again, unless you want to pay import duty.

“We didn’t take any photographs, we were just watching some birds in our telescope.”

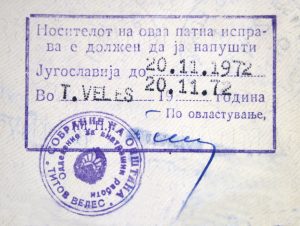

They refused to believe us, and I had to hand over the film roll in my camera, my protests being of no avail. The police officers then put a stamp in our passports, ordering us to leave Yugoslavia the same day. This was not a problem, as a couple of hours’ driving would bring us to the Greek border. We hastily left the unfriendly police officers.

“They are not quite right in their head!” said Arne.

Visas? We thought we would get them at the border, like we did when entering Syria. We spent some nerve-shattering hours on a bench, while the immigration officers called their boss in Baghdad to ask, whether or not we must go back to the Iraqi consulate in Halep to get visas. Just before dusk, the officer handed us back our passports, saying: “Mister, go to Baghdad, to the Residence Department. You will get visas there.”

Experiencing Iraqi bureaucracy in the Residence Department was a farce, which is related in detail on the page Travel episodes – Syria & Iraq 1972: “Welcome to Baghdad!”

“They are not quite right in their head!” said Arne again, when we left the building – an expression that he would often use on the rest of the trip!

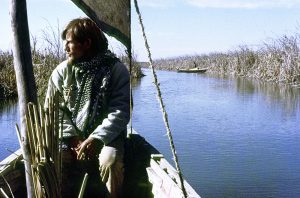

After spending a week in the relatively modern town of Chibayish, we drove further west to the town of Hamar, to be able to visit more unspoiled areas of the marshland. In Hamar, we went to the police station to get permission to rent a boat and a man to punt it into the marshes. As always, no matter where and for what purpose you have come, sweet, strong tea was served in small glasses. There was no hurry. The officers scrutinized our passports and carefully noted our names in a large book – in Arabic script. Arne’s surname, Christoffersen, was indeed troublesome to them. When they learned that we would like to visit the marshes, they instructed us to talk to the mudir, the town mayor, who was also the head of the police force.

We met the mudir at dusk, a small, corpulent man, wearing a Western suit, and sporting a thin moustache. He greeted us somewhat formally and, of course, wanted to know all the facts that we had already presented to the police officers earlier in the day. However, as it turned out, he was a really nice person, who assured us that it was no problem for us to rent a canoe to visit the marshes. He invited us for dinner in his house, and when we asked for permission to sleep in our car, he instructed us to park for the night in front of the police station, as he didn’t want anything to happen to us.

The following day, we went on a lovely trip into the marshes, and in the evening, we were again invited for dinner by the mudir. We asked him for permission to stay a few more days in Hamar, as we would like to go on several trips into the marshes. He readily agreed to this. Every day, he invited us for dinner, and he also saw to it that we got lunch from his house. The lunch was served by his beautiful sister-in-law at our car, which was parked at the lake shore near their house.

In the evening, after dinner, the mudir always wanted to discuss all kinds of topics, which was often a lengthy affair, as his English, to put it mildly, was rather inadequate. As it turned out, his main interests were scantily dressed ladies and sex, which caused many funny incidents. Late in the evening, we parked our car in front of the police station to sleep in it. The officers must have thought that we were very merry, judging from the howls of laughter from the car.

Our adventures in Iraq are described on the pages Travel episodes – Iraq 1973: The hospitable mudir, and Dust storm and sheep’s head.

One day, we were invited to the house of a village leader, named Muhammed, where we spent three weeks. He was indeed a character, causing many unusual or grotesque incidents to occur during our stay, which you may read more about elsewhere, see Travel episodes – Iran 1973: In the mountains of Luristan.

Finally, we left Luristan, driving north to the Caspian Sea to study bird migration along a 70-km-long sand spit, named Mian Kaleh. In this area, we had an accident with our car, as a wheel bearing cracked. We managed to drive to a nearby town, Bandar Shah, where we found a mechanic, named Yasha – a small, powerfully built man, who had emigrated here from Russian Armenia. He spoke Russian, Farsi, and Turkomani, but no English. However, that was hardly necessary to understand our problem.

Some days would pass, before the damage could be repaired, as the spare parts had to arrive from Tehran. We were allowed to sleep in the car on the mechanic’s premises, and the following days were spent in the company of Yasha and his workers, and two of his friends, Ali and Albert, who worked in a bank and spoke a little English. We chatted, ate together, and went on trips into the mountains, bringing beer and packed lunch.

Finally, the spare parts arrived, and the mechanics set to work. In the evening, we had a farewell party, and, although we were not quite sober, we managed to say that we would now like to pay for the work. Yasha blankly refused to accept any payment – we only had to pay for the spare parts!

Our adventures at the Caspian Sea are related in detail on the page Travel episodes – Iran 1973: Car breakdown at the Caspian Sea.

“Kurdistan! Kurdistan! Bum-bum-zip!” said the police officer, using sign language to illustrate how Kurdish bandits would arrive during the night to shoot us and afterwards cut our throat. We tried to make light of it, as other travelers had told us that the Kurdish people didn’t mind foreigners, only Turks. But the officer ordered us to follow their car to the nearest town, Dogubayazit, and spend the night there. You may read more about our trip across Turkey on this page: Travel episodes – Iran & Turkey 1973: “Kurdistan! Bum-bum-zip!”

After Turkey, we stayed some weeks in Greece and Yugoslavia. We had feared that the notorious stamp in our passports would give us trouble entering Yugoslavia, but when the border officers had made a short phone call, they let us enter. In July, we were back in Denmark, after 9 months on the road.

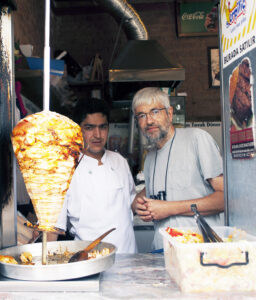

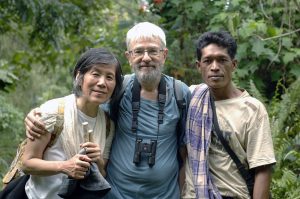

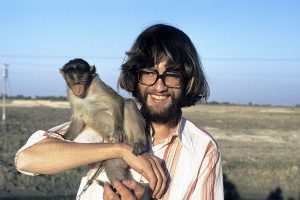

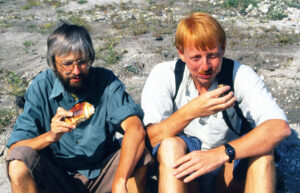

For many years, I worked as a bird watcher and botanist in various Danish scientific nature reserves, and in 1981 I joined a Danish picture agency, Biofoto, through which I sold a lot of photographs during the following twenty years. In 1985, in Indonesia, I met another travelling Dane, Søren Lauridsen. In the period 1991-2015, we wrote several travel guide books together for a Danish publishing agency.

In 1988-1993, I participated in four expeditions to Tanzania, the aim of which was to count wintering waders, and to investigate bird life in coastal forests. In 1989, 1991 and 1998, I participated in expeditions to Arctic seas around Greenland and Iceland to count sea birds and whales.

Quite consciously, I have often travelled to far-away places to meet tribal peoples, some of which have preserved a part of their traditional way of life, and have not yet been transformed into humble servants for the tourism industry – a transition that has taken place with an alarming speed. My interest in nature has also often guided me to areas, where very few tourists come.

At first, many of the exceptional events on my trips often caused irritation or anger. But, in many cases, the strange thing happened that these events, after a shorter or longer period of time, turned into something comical, and – even more remarkable – they became some of the most important events on the whole trip, overshadowing the original purpose of it. Numerous times, my fellow travellers and I have discussed these events, causing us to have yet another hearty laughter.

Other events were not so funny. An episode with robbers in Pakistan showed us that you may run into hostile people when you least expect it. This incident is described on the page Travel episodes – Pakistan 1978: Encounter with robbers.

I was in Iran, before the Ayatollahs usurped Shah Muhammed Riza Pahlevi and his followers. Our trip through Turkey took place, before the Turkish air force bombed Kurdish villages, and the PKK as a retaliation placed bombs in tourist areas around Izmir. For many years now, a civil war has been raging in Syria, and Islamic State activities make travel impossible there.

The rainforest on Borneo now only covers a fraction of its former distribution, and the free way of life of the Dayaks as hunters and fishermen has vanished forever.

During the period 1983 to 2009, a civil war in Sri Lanka made travelling in the eastern and northern parts of the country a very risky affair. The Veddas have long since been engulfed by modern life, as their jungles are today full of dams and hydro-electric power plants, and numerous settlers have occupied their former land (see Travel episodes – Sri Lanka 1974: Among the Veddas, and Sri Lanka 1983: Jungle trip with Ranjan).

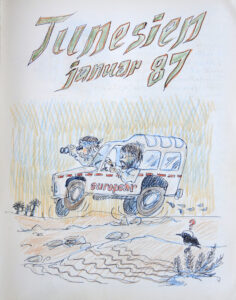

In 1987, shortly after my trip to Tibet, Chinese authorities closed this land to individual travellers, and today there are still quite a few restrictions on travel there.

On the positive side, I would like to mention India and Nepal. The Hindu religion causes Indians and Nepalis to stay some of the most conservative peoples in the World, and, despite nuclear bomb tests in the Thar Desert, computer industry, and the insane traffic in the cities, much is still the same in these countries. In India I get tired and dusty, and I am irritated by foolish questions from students, who want to practice their English on me – but then I am overjoyed by a sunrise in the Himalaya, adding a pinkish glow to the snowy peaks; or a group of Hindu pilgrims, gathered in puja in a temple, dedicated to one of their numerous gods; or a herd of camels, peacefully chewing their cud on a misty morning in the desert of Rajasthan.

In my later years, I have spent long periods with Judy in Taiwan. In general, the Taiwanese are a simple and endearing people, with a colourful and unspoilt religion – a strange blend of Buddhism and Daoism, mixed with many elements from animism, dating back to pre-Buddhist times. (You may read more about this belief on the page Religion: Daoism in Taiwan.)

I am also very fond of the American Southwest, with its superb landscapes and an extremely rich wildlife.

Since 2009, I have been much engaged in taking pictures of mountain flora, especially in the Himalaya, where more than 10,000 species of seed plants are found. The same issue has brought me to montane areas in the Alps, the Pyrenees, Norway, Kyrgyzstan, Taiwan, Chile, the Appalachians, and the Sierra Nevada of California. The flora of several of these mountain areas is described on the page Plants (Himalayan flora, Flora of the Alps and the Pyrenees, Plants of Sierra Nevada, Plant hunting in the Himalaya).

Since those days, the World has changed tremendously. But despite Modern Man’s effort to destroy himself through his insatiable greed, it is still possible to find remote and exotic places on the planet, which afford exciting challenges. I hereby wish my readers Zajagan!