Birds in Turkey

Young rock nuthatch (Sitta neumayer), peeping out from the nesting site inside a ruin in the Ancient Greek town of Hierapolis, Pamukkale. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grey heron (Ardea cinerea), illuminated by evening sun, Igdir, eastern Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Singing male rock sparrow (Petronia petronia), Yazılıkaya, near Hattuşa, Çorum Province. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young hooded crow (Corvus corone ssp. cornix) on a fence near the Galata Tower, Golden Horn, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Western yellow-legged gull (Larus michahellis) on an algae-covered stone, Sultanahmet, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On this page, pictures from 4 visits to Turkey are presented, in 1973, 1975, 2006, and 2018. Families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order. The text is largely based on the websites ebird.org and Wikipedia, the etymology most often on J.A. Jobling 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names, Christopher Helm, London. Nomenclature largely follows the IOC World Bird List (worldbirdnames.org).

Accipitridae Hawks, eagles, and allies

A huge family, comprising about 66 genera and c. 250 species of small to large raptors, distributed worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica.

Buteo Buzzards

A genus of about 28 species, distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. In the Old World, these birds are known as buzzards, whereas the term hawk is often used in North America.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the common buzzard (B. buteo). The English name is derived from Old French busard, which is a corruption of the classical Latin name.

Buteo rufinus Long-legged buzzard

This large buzzard breeds in a vast area, from eastern Europe eastwards to Xinjiang, southwards to Arabia, Iran, and Afghanistan, and also in northern Africa. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter as far south as Bangla Desh, northern India, Iran, Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘golden-reddish’, alluding to the mainly rufous plumage of the bird.

Long-legged buzzard, resting on a pole in front of the mountain Ağrı Dağı (Ararat), near the Iranian border. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Neophron percnopterus Egyptian vulture

This small vulture, the only member of the genus, has a very wide distribution, found from the Mediterranean eastwards across the Middle East to Kazakhstan and the Indian Subcontinent, and in the Sahel Zone of Africa, southwards to northern Tanzania. It also once had a resident population in Angola, Namibia, and South Africa, which is now considered extinct.

Three subspecies are currently recognized, the nominate northern and African birds, which have a mainly grey bill, Indian birds of subspecies ginginianus with a yellow bill, and finally a separate, larger subspecies, majorensis, in the eastern Canary Islands.

It lives in open areas, nesting on cliffs, less frequently in trees. Besides feeding on carcasses, it is often encountered at rubbish dumps, and it will also prey on small mammals, birds, and reptiles. It is among the few bird species known to use tools. Eggs of other birds, which are too large to break open with the bill, are broken by tossing stones onto them, using the bill.

This species is also in decline over much of its range due to habitat destruction, hunting, poisoning, and collision with power lines.

The generic name stems from the Greek mythology. Neophron and Aegypius were young men and close friends, but it upset Neophron that his mother Timandra was having a love affair with Aegypius. To punish Aegypius, Neophron made advances towards Aegypius’ mother, Bulis. He succeeded and enticed Bulis into entering the dark chamber where his mother and Aegypius were soon to meet. Neophron then distracted his mother, tricking Aegypius into entering the chamber and sleeping with his own mother. When Bulis discovered the deception, she gouged out the eyes of her son before killing herself. Aegypius prayed for revenge, but Zeus, instead of helping him, changed both young men into vultures as a punishment.

The specific name is derived from the Greek perknos (‘dark-coloured’) and pteron (‘wing’).

In ancient Egypt, the bird was held sacred to the Moon God Isis, and its protection by Pharaonic law made it common in the streets, giving rise to the name pharaoh’s chicken.

Preening Egyptian vulture, near Karaman. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alaudidae Larks

This family contains 21 genera with about 100 species, distributed in Africa and Eurasia, with a single species reaching the Americas, and a single species in Australia.

Galerida

A small genus with 7 species of crested larks, including species, which were previously placed in the genera Calendula, Heliocorys, and Ptilocorys. These birds are widely distributed in Eurasia and Africa.

The generic name is derived from the Latin galerum (‘cap’) – not a very descriptive name for larks with a crest!

Galerida cristata Crested lark

This bird, divided into about 33 subspecies, is found in a vast area, from central and southern Europe and northern Africa across the Middle East and Arabia to Kazakhstan, northern India, Mongolia, northern China, and Korea, excluding the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau.

Crested lark, Hierapolis, Pamukkale. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ardeidae Herons, egrets, and bitterns

Herons, comprising 18 genera with about 64 species, are long-legged and long-beaked, fish-eating water birds, distributed worldwide with the exception of the polar regions. Some species are called egrets, mainly birds with ornate plumes during the breeding season, whereas birds of the genera Botaurus, Ixobrychus, and Zebrilus are called bitterns.

Many members of the family are presented on the pages Fishing, and Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, Birds in the United States and Canada, and Birds in Africa.

Ardea

A genus with about 13 species of mainly large herons, distributed almost worldwide.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for herons.

Ardea cinerea Grey heron

The grey heron is widely distributed, found in the major part of Eurasia, Africa, and Madagascar.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’.

Other pictures, depicting this bird, are shown on the pages Fishing, Animals: Urban animal life, and Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan, and Birds in the Indian Subcontinent.

In America, it is replaced by the similar, slightly larger great blue heron (A. herodias), presented on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada.

Grey heron, Kuş Gölü, north-western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ciconiidae Storks

These large birds, comprising 6 genera with 19 species, are found in most parts of the world, being absent from the polar regions and the major parts of North America and Australia.

The word stork originates in Ancient Germanic sturkoz.

Ciconia Typical storks

A genus of 7 species, distributed in Africa, Eurasia, and South America.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for storks.

Ciconia ciconia White stork

The white stork is divided into two subspecies, the nominate breeding in the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, eastern Europe, and from Turkey eastwards to northern Iran, and subspecies asiatica, which breeds in Turkestan. The winter months are spent in Africa south of the Sahara, excluding rainforest and deserts, in south-eastern Arabia, and in the Indian Subcontinent.

Previously, the similar, but larger and black-billed oriental stork (C. boyciana) of eastern Asia was regarded as a subspecies of the white stork.

Storks, nesting on the roof of a dilapidated building, between Bergama and Dikili, western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nesting pair of white stork, Alpaslan, northeast of Dinar. A colony of Spanish sparrows (see below) has been established in the bottom of the nest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Feeding stork, between Dikili and Ayvalik, western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Columbidae Pigeons and doves

A large family with about 50 genera and c. 345 species. The word pigeon generally denotes larger species, dove smaller species. These birds are found on all continents except Antarctica.

Spilopelia

Formerly, members of this genus were included in the genus Streptopelia (below), but studies on vocalization, together with genetic analyses, led to the conclusion, that two birds of that genus, the spotted dove (S. chinensis) and the laughing dove (below), differed sufficiently from the other members of Streptopelia to constitute a separate genus. The spotted dove is described on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek spilos (‘spot’) and peleia (‘dove’), referring to the spots on the neck of the spotted dove.

Spilopelia senegalensis Laughing dove

This small dove is widely distributed, found in most of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Middle East, eastwards to India. It is also found in Cyprus. In 1889, it was introduced to western Australia, where populations have been established in several locations. It lives in a variety of habitats, including semi-desert, scrubland, agricultural areas, and cities.

Other names include palm dove and Senegal dove, and in India it is known as little brown dove. The name laughing dove stems from its characteristic cooing, a low, drawn-out croo-doo-doo-doo-doo, somewhat reminiscent of a laughter.

The laughing dove is very common in Istanbul, where this picture was taken. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

“That dove would make a perfect lunch!” – This cat was lying in wait for a laughing dove in Istanbul, but missed it. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Streptopelia Turtle doves

A genus of c. 13 species of small to medium-sized doves, most of which are found in Africa, with several species in tropical and subtropical Asia, one of which, the oriental turtle dove (S. orientalis), is also found in temperate areas of Asia, whereas the collared dove (below) has expanded its distribution area to the Middle East and the entire Europe.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek streptos, which literally means ‘twisted’, but in this connection ‘wearing a torque’ (a twisted necklace), alluding to the semi-collar of many members of the genus; and peleia (‘dove’).

Other species, which were formerly placed in this genus, have been moved to the genera Spilopelia (above) and Nesoenas.

Streptopelia decaocto Collared dove

Originally, the native area of this species was the Indian Subcontinent, but during the Middle Ages it spread to the Near East, reaching Istanbul in the 1700s. In the 1820s, it had spread to the Balkans, whereas the expansion of the major part of Europe took place very rapidly, between the 1930s and 1950s. Today, it is common all over Europe, mainly living in urban areas.

The cooing of this bird is a rather monotonous, continuously repeated “cuh-coooor-cuh”, which can at times be rather annoying. When I was young and prepared for high school examinations, it was quite hot, so I had to leave a window open. A favourite cooing place of a collared dove was our neighbour’s flag pole, situated about 15 m from my window. Its cooing got so annoying that I had to go out and chase it away, but five minutes later it was back on the pole. Well, I did pass my exams anyway.

Various legends are connected with the specific name, which means eighteen in the Greek, from deka (ten) and okto (eight). One legend relates that when Christ was carrying his cross towards Golgotha, a Roman soldier took pity on him, noticing that he was exhausted. By the side of the road, an old woman was selling milk, and the Roman soldier went to her and asked her how much she wanted for a cup of milk. She replied that it would cost eighteen coins. However, the soldier only had seventeen, so he pleaded with her to sell a cupful for seventeen, but the woman refused, and the soldier had to leave without the milk.

When Christ was crucified, the woman was turned into a collared dove and condemned to go around the rest of her days, repeating dekaokto, dekaokto (‘eighteen, eighteen’). If ever she agrees to say dekaepta (‘seventeen’) she will regain her human form, but if she, out of obstination, says dekaenea (‘nineteen’) the world will come to an end.

I wonder how the Greeks managed to make a three-toned call resemble a four-syllable word. But maybe it is pronounced ‘dekokto’?

Collared doves, resting in the top of a cypress, Kuş Gölü, north-western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Collared dove, sitting on a sign, Pamukkale. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Corvidae Crows and allies

This almost cosmopolitan family contains 24 genera with more than 120 species of ravens, crows, rooks, jackdaws, jays, magpies, treepies, choughs, nutcrackers, and others. Due to widespread persecution, most members of the family are very shy. However, many corvids have now adapted to a life in cities, where they are generally left in peace.

Numerous members of this family are described on the page Animals – Birds: Corvids.

Corvus Ravens, crows, rooks

Members of this genus are among the most intelligent birds, and it also contains the largest passerines. Comprising about 45 species, they occur in virtually all temperate areas of the globe, with the exception of South America.

The name raven generally applies to larger species, crow and rook to slightly smaller species. The generic name is the classical Latin word for the raven.

Corvus corone ssp. cornix Hooded crow

Today, various authorities regard the northern European crows as two separate species, the carrion crow, C. corone, and the hooded crow, C. cornix. This is quite puzzling, as the carrion crow, according to this split, is now found in western Europe and the Far East, with a very spotty occurrence in the European part of Russia and Central Asia, and huge areas in between without this species, whereas the hooded crow is found in most of the areas without carrion crows. For this reason, and because the two birds often hybridize, I prefer to regard them as a single species, divided into 6 subspecies.

The carrion crow is all black, whereas the hooded crow is black with grey or white hind neck, wing covers, and belly.

As it is extensively hunted in most of its distribution area, this crow is usually very wary of people, often fleeing at a considerable distance. In many cities, however, where hunting is banned, crows show little fear of people.

The specific name is a Latinized version of korone, the classical Greek word for crow.

Around the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, crows show no fear at all of people, as these pictures clearly show. In the lower picture, a crow is trying to open a zipper on a baby carriage but must give up. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hooded crows, feeding on food, which has been laid out on a ruined wall for feral cats, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Newly fledged hooded crow, near the Galata Tower, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pica Magpies

In the past, only 2 species were recognized in this genus, the black-billed magpie (Pica pica) of Eurasia, North Africa, and western North America, and the yellow-billed magpie (P. nuttalli), which is restricted to California.

However, following genetic research it has been suggested that the former black-billed magpie should be split into a number of separate species, the Eurasian magpie (P. pica), the Maghreb magpie (P. mauritanica) of North Africa, the Asir magpie (P. asirensis) of south-western Saudi Arabia, the Oriental magpie (P. serica) of eastern and southern China, Taiwan, and northern Indochina, the black-rumped magpie (P. bottanensis) of west-central China and the north-eastern Himalaya, and the black-billed magpie (P. hudsonia) of western North America. They are all very much alike, so why this split was made is a mystery to me, and I prefer to regards these magpies as subspecies of a single species.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the magpie, derived from the Latin picata, which, strictly speaking, means ‘smeared with tar’, but in a wider sense ‘black-and-white’.

The word pie is of Indo-European origin, meaning ‘pointed’, in this case no doubt referring to the long, pointed tail of these birds. The prefix mag– dates from the 16th Century, a short form of the name Margaret, which was a term used for women in general. The call of the bird was likened to the chattering of women, and so it was called mag-pie. (Source: etymonline.com/word/magpie)

Pica pica Common magpie

This bird, comprising about 11 subspecies, is found all over Europe, and thence eastwards in a broad belt across temperate areas of Asia to the Pacific coast in north-eastern Siberia, and further on into western North America. The southern limits are north-western Africa, south-western Iran, Ladakh, north-eastern India, northern Indochina, Hainan Island, Taiwan, and south-western United States.

As described above, some subspecies have been upgraded to separate species by some authorities.

Like the hooded crow, the magpie was formerly a shy bird, fleeing from people at a long distance. Today, however, it is a common breeding bird in cities, where, under normal circumstances, people do not constitute a danger to the birds.

The role of the magpie in folklore is described on the page Animals – Birds: Corvids.

Magpies, resting on a pylon, Pamukkale. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Emberizidae Buntings

Following genetic studies, this family now contains only a single genus, Emberiza, with about 45 species, widespread in Eurasia and Africa.

The generic name is derived from the Old German name of these birds, Embritz. The origin of the English name is unknown.

Emberiza hortulana Ortolan bunting

This bird is breeding from Sweden and Finland eastwards to southern Siberia and Mongolia, southwards to the Mediterranean, Turkey, and northern Iran, spending the winter in the Sahel zone of Africa.

In central and southern Europe, it has a spotty occurrence, especially so in France, where it was once common. However, as the bird is regarded as a delicacy here, it has declined drastically, despite being protected by law since 1999. In 2007, the French government announced that it intended to enforce the law, which had until then been largely ignored. Whether they succeed or not remains to be seen.

The specific name is derived from the Latin hortulus (‘belonging to gardens’).

Cretzschmar’s bunting (E. caesia) is quite similar, but has a fainter yellow, sometimes orange throat, with less distinctive black streaks. A picture, depicting this species, is shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Africa.

Male ortolan bunting, Samsun, Black Sea coast. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Emberiza melanocephala Black-headed bunting

This striking bird breeds from the Balkans and Greece eastwards across Turkey and Syria to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and Iran, spending the winter in the Indian Peninsula. Where its breeding area overlaps with that of the closely related red-headed bunting (E. bruniceps), hybridization takes place.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and kephale (‘head’).

Singing male black-headed bunting, Pergamon, western Turkey. (Photo copyright© by Kaj Halberg)

Fringillidae Typical finches

A large family with c. 228 species, divided into about 50 genera. These birds are distributed worldwide, except for Australia and the polar regions. Most species have stout conical bills, adapted for eating seeds and nuts.

Bucanetes

A small genus with only 2 species, distributed on the Canary Islands, in most of northern Africa, and from Egypt across the Middle East to Central Asia.

The generic name is a Latinized version of Ancient Greek bukanetes (‘trumpeter’), alluding to the call of the trumpeter finch (below).

Bucanetes githagineus Trumpeter finch

This small bird is widely distributed, found on the Canary Islands, in northern Africa as far south as Mauritania, Mali, and Chad, with isolated populations in Sudan, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, and also from central and southern Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula eastwards to Kazakhstan and north-western India. Since 1971, it has colonized a small area in southern Spain.

The specific name refers to the corn-cockle (Agrostemma githago). The connection is obscure.

This young male trumpeter finch had strayed from the normal distribution area of the species. It was observed on the Black Sea coast, between Ünye and Terme. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hirundinidae Swallows and martins

A large family with 19 genera and about 90 species, distributed around the world on all continents, including Antarctica, where the barn swallow (below) is an occasional visitor. The greatest diversity is found in Africa.

In Europe, the term swallow is mainly used for species with forked tails, martin mainly for species with squarish tails. In America, however, the term martin is reserved for members of the genus Progne.

Cecropis

A small genus of 9 species, distributed in warmer areas of Africa and Asia, with a single species, the red-rumped swallow (below), also occurring in southern Europe. Some authorities include these birds in the genus Hirundo (below).

The genus may be named for Kekropia, a mythical king of Athens. Jobling (2010) mentions Kekropis, a woman from Athens, without further explanation.

Cecropis daurica Red-rumped swallow

This species, previously known as Hirundo daurica, is widely distributed, found in Africa southwards to the Sahel zone and Zambia, and from southern Europe eastwards across Kazakhstan and Mongolia to south-eastern Siberia and Japan, and thence southwards to central India and northern Indochina.

The specific name refers to Dauria, a landscape in south-eastern Siberia, in which a nomadic Mongolian tribe, the Dauuri or Daguuri, once lived. Presumably the type specimen was collected there.

Some subspecies of this bird are extremely similar to the striated swallow (C. striolata), which breeds in north-eastern India, southern China, Taiwan, Indochina, and the Philippines, with disjunct populations from Java eastwards to Timor. Striated tends to be a little larger and with less rufous on crown and cheeks, but the two species are very difficult to separate in the field. To me, it is a bit of a mystery why they are not regarded as a single species. Pictures, depicting the striated swallow, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Red-rumped swallows, house martins, and barn swallows (both described below), collecting mud for nest-building, Tatlisu, Kapıdağ Peninsula, Marmara Sea. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Delichon House martins

A small genus with 4 species, distributed in Eurasia and Africa.

The generic name is an anagram of chelidon, a Latinized version of Ancient Greek khelidon (‘swallow’).

Delichon urbicum Common house martin

This bird breeds in a vast area, from Norway, the British Isles, and Portugal eastwards to western Siberia, northern Xinjiang, and western Mongolia, southwards to north-western Africa, Jordan, Iran, and Afghanistan. It spends the winter months in Africa south of the Sahara, and to a lesser extent in Arabia and southern India.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living in towns’.

Previously, populations further east in Asia were regarded as belonging to this species, but have since been split to form two other species, Asian house martin (D. dasypus) and Siberian house martin (D. lagopodum).

House martins, red-rumped swallows, and a single barn swallow, collecting mud for nest-building, Tatlisu, Kapıdağ Peninsula, Marmara Sea. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

House martins and barn swallows take off, Tatlisu. The plant in the background is common mallow (Malva sylvestris). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hirundo

This genus contains about 16 species, all but one restricted to the Old World. The barn swallow (below) also occurs in the Americas.

The generic name is the Latin word for swallow.

Hirundo rustica Barn swallow

This bird is the most widespread swallow in the world. It mainly nests on or inside buildings, very often in stables or barns – hence its name. Six subspecies are spread across the major part of the Northern Hemisphere, from the British Isles eastwards to Japan, and from northern Norway, central Siberia, and Kamchatka southwards to North Africa, Egypt, southern Iran, and southern China, and in most of North America, from northern Canada southwards to southern Mexico. Four of the subspecies are migratory, spending the winter as far south as South Africa, northern Australia, and Argentina. The birds may be seen year-round in southern Mexico, southern Iberian Peninsula, Egypt, the Himalaya, southern China, and Taiwan.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘living in the countryside’.

A number of pictures, depicting the subspecies gutturalis, are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Barn swallow and house martin, collecting mud for nest-building, Tatlisu, Kapıdağ Peninsula, Marmara Sea. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Laniidae Shrikes

Shrikes are a group of striking passerines, which perch on trees, bushes, poles, or wires, scanning the surroundings for small prey, such as beetles, dragonflies, bees, lizards, and mice. They constitute a small family with 34 species in 2 genera, mainly distributed in Eurasia and Africa, with one species reaching New Guinea, and 2 in North America.

Previously, the family was much larger, including bushshrikes, puffbacks, tchagras, boubous, and helmetshrikes. However, genetic research has shown that these groups are not closely related to shrikes. As a consequence, bushshrikes, puffbacks, tchagras, and boubous have been moved to the family Malaconotidae, helmetshrikes to the family Vangidae.

Lanius Typical shrikes

The major part of the 32 species in this genus occur in Eurasia and Africa, with one species in New Guinea, and 2 in North America.

The generic name is derived from the Latin lanio (‘butcher’), derived from laniare (‘tearing to pieces’). Shrikes were formerly known as ‘butcher-birds’, referring to their habit of storing prey by impaling it on thorns and sharp twigs, thus resembling a butcher’s slaughterhouse. The name shrike stems from Old English scric, alluding to their call.

Lanius senator Woodchat shrike

This bird lives in rather open areas, found from central and southern Europe eastwards to the Caucasus and Iran, southwards to northern Africa, Jordan, and Kuwait, spending the winter in Africa south of the Sahara, southwards to Gabon, northern Zaire, Uganda, and northern Kenya.

The specific name supposedly alludes to the chestnut-red colour on crown and nape of the bird, which resembles the colour of the band on the togas of Roman senators.

Male woodchat shrike, between Eceabat and Gelibolu, western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Laridae Gulls, terns, and skimmers

This large cosmopolitan family constitutes 22 genera with about 100 species.

Larus

Formerly, most gulls were placed in this genus, but genetic research has lead to the resurrection of the genera Ichthyaetus, Chroicocephalus, Leucophaeus, and Hydrocoloeus. The systematics of the larger species is very complicated, and a number of former subspecies have recently been elevated to separate species. Today, the genus may contain about 30 species.

Larus michahellis Western yellow-legged gull

This species is found in the Mediterranean Sea. It resembles the herring gull (L. argentatus), but can be identified by its yellow legs and very powerful beak. It is extremely common in Turkey.

Western yellow-legged gull at its breeding site on coastal rocks at Şile, Black Sea. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Western yellow-legged gulls with chicks in their nests, built on house roofs in Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This western yellow-legged gull, resting on a lamp, is chased away by another bird, Istanbul. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Western yellow-legged gull, drinking from a fountain, oblivious of the courting couple in the background, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Meropidae Bee-eaters

This family contains 3 genera and about 27 species of medium-sized, insect-eating birds, most of which are found in Africa and Asia, with a few in southern Europe, Australia, and New Guinea. They are characterised by having a curved bill, a slender body, and usually a long tail, and many are gorgeously coloured.

Merops

The vast majority of bee-eaters, about 24 species, are placed in this genus.

The generic name is the classical Greek name of the common bee-eater (below). Originally it meant ‘endowed with speech’, used in poetry to describe articulated people who ‘divided voices’, from meros (‘part’) and ops (‘voice’).

Merops apiaster Common bee-eater

This species breeds in two widely separated areas. The larger population is distributed from central and southern Europe and northern Africa eastwards to southern Siberia and Afghanistan, and a few places in Arabia, wintering in Africa south of the Sahara. The other, smaller population is resident in South Africa, maybe originally established from migratory birds, which, for some reason, stayed in the area.

The specific name is from apiastra, the classical Latin name of the common bee-eater, derived from apis (‘bee’).

Common bee-eaters near their breeding site, between Eceabat and Gelibolu, western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Muscicapidae Old World flycatchers

Genetic research has revealed that many smaller birds, which were formerly regarded as belonging to the thrush family (Turdidae), are in fact flycatchers.Today, the family includes about 51 genera with c. 324 species, widely distributed in Africa and Eurasia. The family name is derived from the Latin musca (‘a fly’) and capere (‘to catch’).

Oenanthe Wheatears

Following a number of genetic studies, this genus today contains about 32 species, as members of the former genus Cercomela are now included in Oenanthe.

These birds are widely distributed in Europe, Asia, and Africa, with a single species, the northern wheatear (below), also breeding in Greenland and eastern Canada, and in Alaska and western Canada.

The generic name is derived from the Greek oenos ‘wine’ and anthos (‘flower’), alluding to the northern wheatear returning from Africa to Greece in spring, when the grapevines blossom.

The common name is an old folk name of the northern wheatear, meaning ‘white arse’, referring to the conspicuous white rump of the bird.

Oenanthe melanoleuca Eastern black-eared wheatear

This bird was formerly considered conspecific with the western black-eared wheatear (O. hispanica), and some authorities do not acknowledge the split. Both species have two morphs, one with a black throat, and one with the throat being the same colour as the breast.

The eastern species/subspecies breeds from southern Italy and the Balkans eastwards through Turkey and the Levant to south-western Kazakhstan and western Iran, wintering in the central and eastern parts of the Sahel zone in Africa, eastwards to the Red Sea.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek melas (‘black’) and leukos (‘white’), thus ‘pied’.

Male eastern black-eared wheatear, black-throated phase, eating a caterpillar, Pergamon, western Turkey. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oenanthe oenanthe Northern wheatear

The northern, or common wheatear breeds in a vast area, in almost the entire Europe, from Iceland and northern Norway southwards to the Mediterranean, and thence eastwards across Siberia, Turkey, Iran, and Central Asia to Alaska and north-western Canada, and also in Greenland and extreme north-eastern Canada.

The strange thing is that the entire population winters in Africa south of the Sahara. This means that birds from Greenland and eastern Canada cross the Atlantic, a distance of about 3,000 km. Birds from western Canada and Alaska fly all the way across Asia. One should think that evolution had caused some populations to choose other wintering areas, but this is not the case.

A very pale male northern wheatear, Demirkazik, Ala Dağları, southern Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phoenicurus Redstarts

This genus contains 14 species, distributed from western Europe and North Africa eastwards across Temperate Eurasia, and thence southwards to India and Indochina. Most of the species are strongly sexually dimorphic, females being much less colourful than males.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek phoinix (‘crimson’) and oura (‘tail’), like the English name referring to the reddish tail of these birds. Start is an old word for tail.

Phoenicurus ochruros Black redstart

Divided into about 8 subspecies, this bird is widely distributed, breeding from Europe (except the northernmost parts, Scotland, and Ireland) and the Middle East eastwards across Central Asia to central China, southwards to the northern parts of the Himalaya. It winters in southern Europe, northern and north-eastern Africa, Arabia, the Middle East, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The plumage varies considerably, males of the eastern subspecies having a black mask and upper breast, slaty-grey upperparts, and rufous belly and tail, whereas those of the western subspecies are blackish with whitish vent and secondaries, and a rufous tail.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek okhros (‘pale yellow’) and oura (‘tail’) – an odd name, as the tail of all subspecies is rufous.

Male black redstart, Ilgaz, between Çankiri and Kastamonu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Passeridae Old World sparrows, snowfinches

As the family name implies, these birds, comprising about 43 species in 8 genera, are restricted to the Old World. They are not closely related to the New World sparrows, which belong to the family Passerellidae. When the European settlers arrived in America, these birds reminded them of the sparrows back home, so they named them ‘sparrows’.

Passer Typical sparrows

A genus of about 28 species, widely distributed in Africa and Eurasia. The generic name is the Latin word for sparrows.

Passer domesticus House sparrow

This well-known bird was originally native to Europe, northern and north-eastern Africa, and most temperate and subtropical areas of Asia, but has been introduced to almost the entire planet. In many areas, where it was previously common, it has declined dramatically in later years, mainly due to the increased usage of chemical fertilizers and insecticides.

In Turkey, much hybridization takes place between the house sparrow and the closely related Spanish sparrow (below).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘belonging to houses’, derived from domus (‘house’).

Other pictures, depicting this species, may be seen on the pages Animals: Urban animal life, and Nature: Invasive species.

Male house sparrow at its breeding site above the entrance to Pamukkale. Its spotted upper breast indicates hybridization with Spanish sparrow. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Passer hispaniolensis Spanish sparrow

This bird is very similar to the closely related house sparrow (above), and the two species often hybridize. The underparts of the male are heavily streaked with black, its crown is chestnut, not grey as in the house sparrow, and the cheeks are white, not grey. The female has light streaking on the sides and a clear supercilium.

It is distributed from the Kap Verde and Canary Islands across the Mediterranean and the Middle East to Kazakhstan and Pakistan.

The specific name is derived from Hispania, the classical Latin name of Spain. The type specimen originated from this country.

A colony of Spanish sparrows has been established in the bottom of this nest of white stork, Alpaslan, northeast of Dinar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female Spanish sparrows on coastal rocks, near Şile, Black Sea. Note light streaking on the sides and a clear supercilium. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Petronia petronia Rock sparrow

This species is now the only member of the genus Petronia, as other, former members have been moved to the genera Gymnoris and Carpospiza.

The rock sparrow is distributed in barren rocky areas, from the Canary Islands, the Iberian peninsula, and northern Africa across the Mediterranean and the Middle East to Xinjiang, Mongolia, and northern China. Birds in Central Asia migrate south in the winter, or to lower elevations in montane areas.

The generic and specific names are a local Bolognese name for this bird, stemming from Ancient Greek petros (‘rock’), alluding to its habitat.

Male rock sparrow, Yazılıkaya, near Hattuşa, Çorum Province. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pelecanidae Pelicans

These huge water birds have an enormous bill and a very large gular pouch, which swells tremendously, when the bird is fishing – like some kind of basket. The tongue, however, is quite small, allowing the bird to swallow large fish.

Formerly, it was presumed that the gular sac was a means to store food for several days, but this is not the case. This belief was the cause of a funny limerick, written in 1910 by American poet Dixon Lanier Merritt (1879-1972):

Oh, a wondrous bird is the pelican!

His beak holds more than his belican.

He takes in his beak

Food enough for a week.

But I’ll be darned if I know how the helican.

There are 8 species in one genus, Pelecanus. Formerly, they were divided into two groups, one with 4 species, having a mainly white adult plumage, the great white pelican (below), the Dalmatian (P. crispus), the American white (P. erythrorhynchos), and the Australian (P. conspicillatus), and another, containing the remaining 4 species, having a mainly grey or brown adult plumage, the pink-backed (P. rufescens), the spot-billed (P. philippensis), the brown (P. occidentalis), and the Peruvian (P. thagus).

However, recent DNA research has revealed that the 5 Old World species (great white, Dalmatian, pink-backed, spot-billed, and Australian) form one lineage, whereas the American white, the brown, and the Peruvian form another. The great white was the first to diverge from the common ancestor, which suggests that pelicans evolved in the Old World and later spread into the Americas.

Traditionally, pelicans were thought to be related to cormorants, darters, gannets, frigatebirds, and tropicbirds, but genetic research has shown that they form an order, Pelecaniformes, together with herons, the hamerkop (Scopus umbretta), and the shoebill (Balaeniceps rex).

Pelecanus onocrotalus Great white pelican

This bird has a huge distribution, breeding at scattered locations from south-eastern Europe eastwards to Kazakhstan and north-western India, and in the major part of Africa. Northern populations are migratory, spending the winter in Africa, Arabia, the Middle East, and the Indian Subcontinent.

The specific name is a Latinized version of onokrotalos, the classical Greek word for pelicans.

White pelicans at their breeding site, Kuş Gölü, north-western Turkey. Due to lack of suitable nesting places, scaffolds have been erected for the birds to build their nests on. Great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo, see below) also nest here. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phalacrocoracidae Cormorants

Cormorants and shags are a cosmopolitan family of about 41 species of small to medium-sized, fish-eating birds. Recent genetic studies have concluded that these birds should be placed in 7 genera: Phalacrocorax (12 species), Leucocarbo (16 species), Microcarbo (5 species), Urile (3 species), Nannopterum (3 species), Gulosus (European shag, below), and Poikilocarbo (red-legged cormorant).

Numerous cormorant species are presented on the pages Fishing, Silhouettes, Animals – Birds: Birds in the United States and Canada, and Birds in Africa.

Gulosus aristotelis European shag

This bird, the only member of the genus, is widely distributed along rocky coasts of Europe, from the Kola Peninsula, northen Norway, and Iceland via the British Isles, France, Spain, and Portugal to Morocco, and many places in the Mediterranean and Black Seas.

There are 3 subspecies, aristotelis, which breeds along the European Atlantic coasts, desmarestii, which is found along Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts, and riggenbachi, which is restricted to Morocco.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘gluttonous’, whereas the specific name honours Greek philosopher, historian, and naturalist Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), whose 10-volume work Ton peri ta zoia historion (‘Enquiry concerning animals’, or ‘Historia animalium’) is considered among the beginnings of descriptive zoology. (Jobling, 2010)

European shags, eastern subspecies desmarestii, at their breeding site, coastal rocks near Şile, Black Sea. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phalacrocorax

At present, this genus contains 12 species. The generic name is derived from the Greek phalakros (‘bald’) and korax (‘raven’), where ‘bald’ refers to the white (but feathered) crown of the great cormorant (below) during the breeding season, whereas ‘raven’ presumably alludes to its otherwise black plumage.

Phalacrocorax carbo Great cormorant

This bird has an extremely wide, but rather patchy, distribution, found all over Europe and most of Asia, in Australia and New Zealand, and in north-eastern North America and Greenland.

In the 1800s, itwas persecuted all over Europe, partly because it was competing with fishermen, partly because its guano destroyed the trees, in which it was breeding. The complete contrast to this persecution is seen in the Far East, where fishermen, for thousands of years, have been using tamed great cormorants for fishing. Pictures, depicting this practice, are found on the page Fishing.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘charcoal’, naturally alluding to the colour of this bird.

Great cormorants and white pelicans (see above) at their breeding site, Kuş Gölü, north-western Turkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Procellariidae

A large family of seabirds, comprising fulmarine petrels, gadfly petrels, diving petrels, prions, and shearwaters, altogether about 99 species in 16 genera.

These birds are characterized by having tubular nasal passages on the upper mandible, to which a gland is attached. When feeding, they invariably swallow a lot of sea water, and surplus salt in their bodies is excreted through this gland.

Puffinus Shearwaters

A genus with about 21 species, distributed across the globe. The taxonomy of the genus is the cause of much debate, and the number of recognized species varies according to authority.

The generic name is based on the English word puffin. This word and its variants, including poffin and puffing, refers to the cured carcasses of fat nestlings of the shearwater, which were regarded as a delicacy in the old days. The word puffin dates back from at least 1337, but during the 1600s, the term was gradually used for another seabird, the Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica). (Jobling, 2010)

The common name was given in allusion to the habit of these birds of flying very low over the water, seemingly ‘shearing’ it with their wing tips.

Puffinus yelkouan Yelkouan shearwater

In former days, this bird was considered a subspecies of the Manx shearwater (P. puffinus), but was then split from that species, and, together with birds from the Balearic Islands, named Mediterranean shearwater. Today, it forms a monotypic species in the central and eastern Mediterranean, as Balearic birds are now also regarded as a separate species, the Balearic shearwater (P. mauretanicus). What complicates the matter is that at least one mixed breeding colony of yelkouan and Balearic shearwaters is found on the Balearic island Menorca.

The unusual name of this species is derived from a Turkish word, yelkovan, meaning ‘wind-chaser’.

This picture shows part of a flock of c. 1,500 yelkouan shearwaters and 1,500-2,000 western yellow-legged gulls (see above), feeding on sardines (Sardina pilchardus) in the Marmara Sea, Istanbul. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sittidae Nuthatches

Nuthatches are a family of c. 29 species of small passerines, all placed in the genus Sitta. These birds are characterized by their feeding behavior, creeping up and down tree trunks in search of larvae, which they extract from the wood, using their powerful bill.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sitte, a bird like a woodpecker, mentioned by Greek grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria (5th or 6th Century A.D.), and also by Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle (384-322 B.C.).

Sitta neumayer Western rock nuthatch

This bird breeds in rocky areas, from the Balkan Peninsula and Greece eastwards across Turkey, Lebanon, and northern Syria to the Caucasus and western Iran. Further east, it is replaced by the similar, but larger eastern rock nuthatch (S. tephronota).

The specific name commemorates Austrian naturalist and natural history dealer Franz Neumayer (1791-1842), who lived in Dubrovnik, collecting natural history items in the surrounding area.

Rock nuthatches, breeding in ruins of the Ancient Greek town of Hierapolis, Pamukkale. Two of the birds bring food for their young. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young rock nuthatch, Hierapolis. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Strigidae Typical owls

A large family with 25 genera and nearly 220 species. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica.

Athene

This genus, containing 9 species, is found on all continents, with the exception of Australia and Antarctica.

In Greek mythology, the little owl (below) represented or accompanied Athene, the virgin goddess of wisdom. Because of this association, owls were often regarded as a symbol of knowledge and wisdom in the West.

Athene noctua Little owl

This small owl breeds in a vast area, from Denmark and Estonia southwards to the Mediterranean, and northern and north-eastern Africa, and from southern Russia, Turkey, the Middle East, and Arabia across Central Asia to Ussuriland, in south-eastern Siberia, and northern Korea. It has also been introduced to England and New Zealand.

The specific name was the Ancient Roman name for this owl, which was sacred to the goddess Minerva, the Roman equivalent for the Greek goddess Athene.

Little owl, near Izmir. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sylviidae Sylviid babblers

This family was once huge, containing all ‘warblers’, but genetic research has caused the vast majority to be moved to other families, leaving only 32 species in the family, divided into 2 genera, Sylvia and Curruca. These birds are widespread in Eurasia and Africa.

Curruca

A genus with 25 species, split from the genus Sylvia in 2014.

The generic name is the name used for an unidentified small bird, mentioned by Roman poet Decimus Junius Juvenalis (born about 55 A.D.).

Curruca ruppeli Rüppell’s warbler

This species breeds in Greece and western Turkey, living in maki and other drier areas. It is migratory, spending the winter around the south-eastern coast of the Mediterranean, westwards to Egypt.

It was named in honour of German naturalist and explorer Wilhelm Peter Eduard Simon Rüppell (1794-1884), who collected numerous specimens of plants and animals in Africa.

Rüppell’s warbler, between Urla and Mordogan, near Izmir. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Threskiornithidae Ibises and spoonbills

A worldwide family with 14 genera of long-legged water birds, found on every continent, except Antarctica. Traditionally, this family has been classified into two subfamilies, the ibises and the spoonbills. However, a recent genetic study concludes that spoonbills are closely related to the Old World ibises, whereas the New World ibises are an early offshoot. (Source: J.L. Ramirez, C.Y. Miyaki & S.N. del Lama 2013. Molecular phylogeny of Threskiornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Genetics and Molecular Research 12 (3): 2740-2750)

Geronticus Bald ibises

A small genus with only 2 species, the northern bald ibis (below), and the southern bald ibis (G. calvus), which is restricted to South Africa, Lesotho, and Eswatini.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek geron (‘old man’), referring to the bald crown of these birds.

Geronticus eremita Northern bald ibis

This species was once widespread across the Middle East, northern Africa, southern Europe, and the Alps. However, it disappeared from Europe more than 300 years ago, and the other populations also plummeted. By the mid-1900s, only two colonies were known, in southern Morocco and in the town of Birecik, on the banks of the Euphrates River in southern Turkey, near the Syrian border.

Formerly, the ibises in Birecik were held in high esteem, as it was believed that the birds, when on migration, would guide Muslim pilgrims on their Hajj (pilgrimage) towards Mecca. Each spring, a festival would be held to celebrate the return of the birds. Despite this, its decline continued, and in 1972 only 26 pairs were breeding in Birecik.

At this point, a well-known Turkish bird painter, Salih Acar, his wife Belkis, and Udo Hirsch, a young German ethnologist and wildlife photographer, began their struggle to preserve the birds, for example by constructing artificial breeding platforms on the rock face above the town.

Udo Hirsch once said, “Generations ago, the ibises built good, deep nests. Its eggs are very round, not oval, and roll easily. Today, the ibis nests in Birecik are nests only by courtesy. They are flat bunches of twigs, plastic-bags, and grass, and one good kick by a startled adult bird can easily throw an egg out of the nest and right off the ledge. The same is true of nestlings: as they squabble for food, the smallest are often bullied out of the nest, falling 40 feet.”

As it turned out, their efforts bore fruit. In the 1980s, the Turkish National Park Service decided to stop the decline of the ibis by taking all birds into semi-captivity. Two large aviaries were built to house the birds in winter. Each year, they are caught in July or August and kept in the center until March, when they are released to breed in their natural habitat. Some also breed in artificial nests on the rock wall, where the nesting shelves are tipped inward to prevent egg and chick loss. Today, there are well over 100 breeding pairs. (Source: traveltoeat.com/saving-the-northern-bald-ibis-birecik-turkey)

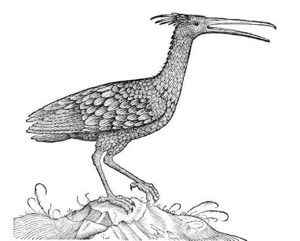

The first description and illustration of a northern bald ibis appeared in Historiæ animalium, Liber III, published in 1555 by Swiss physician and naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516-1565). He named it Corvus sylvatico (‘forest crow’), which in Old German became waldrapp – a name which has stuck to this day.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek eremía (‘desert’), alluding to the barren habitats of the species.

In Birecik, Turkish and German conservationists constructed artificial breeding platforms for the bald ibises on the rock face above the town. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Northern bald ibis. Illustration from Historiæ animalium. (Public domain)

(Uploaded November 2023)

(Latest update October 2024)