Reptiles in Africa

Mating green turtles (Chelonia mydas), near Boydu Island, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Portrait of a flap-necked chameleon (Chamaeleo dilepis), Masasi, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) in morning light, Lake Baringo, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Giant plated lizard (Matobosaurus validus), Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis), Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This page deals with a selection of reptiles, which I have encountered during several visits to Africa between 1980 and 2003.

Families, genera, and species are presented in alphabetical order.

A number of pictures, depicting unidentified species, are also shown here. If you are able to identify any of these animals, or if you find any errors, I would be grateful to receive an email. You may use the address at the bottom of this page.

I have used the former name Zaire for the country today officially known as The Democratic Republic of Congo, as I find that name somewhat laborious. Furthermore, you can hardly place the term ‘democratic’ on a country that, for decades, has been pervaded by a chaos of violence.

Agamidae Agamas

Agamas are a large group of lizards, comprising 6 subfamilies with about 64 genera and more than 300 species, distributed in Asia, Australia, Africa, and southern Europe.

Agama

A genus with about 50 species, found in the entire Africa and on Madagascar. Previously, a number of Eurasian species were included in the genus, but have since been moved to other genera.

The generic name is probably of West African origin, but apparently it was a name used for chameleons.

Agama armata Tropical spiny agama

The male of this agama, also known as northern ground agama or Peter’s ground agama, has more subtle colours than most agamas, being mainly grey, although displaying males have a turquoise or bluish head and a reddish-brown body.

It is widespread from southern Zaire and southern kenya southwards to South Africa.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘armed’, like the common name alluding to numerous tiny spines on the body of this species.

Tropical spiny agama females on a termite mound, Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agama etoshae Etosha rock agama

This agama is restricted to a rather small area around Etosha National Park, northern Namibia. It was described as late as 1981.

Etosha rock agama, Etosha National Park, Namibia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agama kirkii Kirk’s rock agama

This animal is found from southern Tanzania southwards through Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, and eastern Botswana to Mozambique.

It was named in honour of British physician, naturalist, and Governor General of Zanzibar, Sir John Kirk (1832-1922), who collected many plants and animals in eastern Africa and published numerous papers. Many species are named after him, including this agama. He was also the leading figure in ending the slave trade in Zanzibar, with the aid of his political assistant, Ali bin Saleh bin Nasser Al-Shaibani.

Male Kirk’s rock agama, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agama lionotus Kenyan rock agama

The male is bright blue with an orange head, whereas the female is pale brown with blackish rectangular spots and white dots. This species is distributed in eastern Africa, from Ethiopia southwards through Kenya and Uganda to Tanzania.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek leios (‘smooth’) and noton (‘back’).

Male Kenyan rock agama, sitting on a termite mound, Lake Bogoria, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agama mwanzae Mwanza flat-headed rock agama

This species lives in savannas and semi-deserts in Kenya, Rwanda, and Tanzania. It is often observed in the heat of the day, basking on rocks. Head, neck, and shoulders of the male are violet or dark red, the rest of the body dark blue.

It was named after the type locality, the town of Mwanza in north-western Tanzania.

Mwanza flat-headed rock agama males, basking on rocks, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At some point, this male in Serengeti National Park lost its tail, and a new one is growing out. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A male and three females, basking on the skull of an African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), which has been placed as decoration on a rock outside a hotel, Serengeti National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Agama planiceps Namibian rock agama

This striking animal is restricted to rocky areas of western Namibia and south-western Angola. The male looks like most other males of the genus, with a bright red head and a dark blue body, but may easily be identified by the whitish base of the tail. Females are dark with white or yellow spots and stripes on the head and a white stripe down the back.

The specific name is derived from the Latin planus (‘flat’) and –ceps (‘-headed’).

Male Namibian rock agama, basking on a rocky outcrop, Daan Viljoen National Park, Namibia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Uromastyx Spiny-tailed lizards

A genus with about 15 species, found in arid areas of Africa north of the Sahel zone, in the Arabian Peninsula, and in the Middle East, eastwards to Iran.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek oura (‘tail’) and mastix (‘whip’), alluding to the spikes on the tail of these lizards.

Uromastyx acanthinura North African spiny-tailed lizard

This species is widespread in desert areas of northern Africa, from Morocco eastwards to Egypt, southwards to Mali, Niger, and Sudan.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek akantha (‘thorn’) and oura (‘tail’), like the generic name alluding to the spiny tail of this species.

Female North African spiny-tailed lizard, north of Assamaka, Niger. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaeleonidae Chameleons

This family of unique reptiles, comprising 12 genera with more than 200 species, is distributed in Africa, Madagascar, southern Spain, Corsica, Sardinia, southern Italy, southern Greece, the Near East, the Arabian Peninsula, southern India, and Sri Lanka. The vast majority of the species are found in Africa south of the Sahara, and in Madagascar.

The eyes of these animals move independently, and they are able to analyze two different images simultaneously when hunting for prey. When a suitable prey has been spotted, the chameleon projects its very long, sticky, folded-up tongue at a tremendous speed at the prey, often from quite a distance. The poor victim sticks to the tongue, which is then folded up and retracted into the mouth, prey and all.

Chameleons are also able to change colour very fast, which mostly happens when they get excited. An example is shown below under Chamaeleo dilepis.

The family name is derived from the Greek khamai (‘on the ground’) and leon (‘lion’), thus ‘earth-lion’, undoubtedly alluding to the hunting method and voracious appetite of these animals.

Several species are popular pets, and some places they have escaped (or have been released) to form feral populations, which are often a threat to the local insect fauna – and thereby indirectly to insectvorous birds, and plants which are dependent on insects for pollunation. This is seen in Hawaii and other places.

Unidentified chameleon, maybe Chamaeleo anchietae (see below), Geita, north-western Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaeleo

Today, this genus contains about 14 species. Previously, it was much larger, but the major part of the species have been moved to other genera.

Chamaeleo africanus African chameleon

Also known as the Sahel chameleon, this animal is found in the Sahel zone, living in savannas from Mauritania eastwards to Sudan, and thence northwards along the Nile to Egypt. It is a large species, growing to 34 cm long, including the tail. It is often green with many black spots and lateral yellow stripes along the side of the body. It has a large bony casque on its head.

At some stage, it was brought from Egypt to Peloponnese, Greece, which today has a small population of about 350 individuals.

African chameleon, north of Malbaza, Niger. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaeleo anchietae Double-scaled chameleon

This species occurs from Angola and southern Zaire eastwards to western Tanzania.

The specific name honours Portuguese explorer and naturalist José Alberto de Oliveira Anchieta (1832-1897), who travelled extensively in Portuguese Angola between 1866 and 1897, where he collected a large number of animals and plants. He died in Angola, presumably of malaria.

Double-scaled chameleon, Sao Hill, western Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chamaeleo dilepis Flap-necked chameleon

Divided into 8 subspecies, this chameleon is widespread and common in sub-Saharan Africa, from Cameroun eastwards to Ethiopia and Somalia, and thence southwards to northern South Africa. It lives in a variety of habitats, including savannah, woodland, shrubberies, and bushy grasslands, and it is also often encountered in villages and suburbs.

It is a large species, up to 35 cm long, including the tail. It may be green, yellowish, or brownish, but there is usually pale stripes on the flanks and underside.

The specific name is Ancient Greek, meaning ‘with double scales’, which may refer to the pattern on the gular sac, where rows of green double-scales alternate with rufous bands (see picture below).

The common name alludes to two flaps on the hind neck, similar to those of the African chameleon (above).

Flap-necked chameleon, west of Lindi, southern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flap-necked chameleon, Masasi, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one clings to my companion Jens Bagger’s T-shirt, Masasi. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This flap-necked chameleon displays a considerable change of skin colour in a short period of time, Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This female is digging a hole to lay eggs, Rondo Forest. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kinyongia

Most members of this genus, comprising about 23 species, are characterized by the males, and in some species also the females, having horns or knobs on their noses. They were formerly placed in the genus Bradypodion.

With the exception of K. adolfifriderici and K. tavetana, these animals are restricted to mountains in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and far eastern Zaire, and almost all have a very small range.

The generic name is the Kiswahili name of these chameleons.

Kinyongia multituberculata West Usambara two-horned chameleon

As its name implies, this chameleon is endemic to the West Usambara Mountains in northern Tanzania. It lives in forest, scrubland, and along roads, at elevations between 1,200 and 2,500 m.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘with many warts’, presumably alluding to the knobby horns of this species.

West Usambara two-horned chameleon, Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trioceros

This genus contains about 41 species, which are found in tropical regions of Africa. They were formerly included in the genus Chamaeleo (above).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tri (‘three’) and keras (‘horn’), alluding to the fact that some (but far from all) members of the genus have 3 horn-like protruberances on the forehead and nose.

Trioceros bitaeniatus Side-striped chameleon

This species, also known as two-lined chameleon, is native from Ethiopia and southern Sudan southwards to northern Tanzania, and thence westwards through Uganda to north-eastern Zaire. It mainly lives in montane areas, and on Mount Kenya it has been encountered at elevations above 3,000 m.

The specific name is derived from the Latin bi– (‘occurring twice’), and from Ancient Greek tainia (‘ribbon’), referring to two lines along the side of the body.

Side-striped chameleon, sitting on an umbellifer, Kalonga, Ruwenzori Mountains, eastern Zaire. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trioceros chapini Chapin’s chameleon, grey chameleon

Not much is known about this species. It was first collected during the Lang-Chapin expedition 1909-1915, which made a comprehensive biological survey of the Belgian Congo, as Zaire was called in those days. Since then, very few specimens have been collected. It seems to be distributed from Gabon and Equatorial Guinea eastwards to central Zaire.

According to Chapin, the general colour of the male is dark grey, with a few blackish bars, and a faint tinge of rufous in the light areas of the body. These characters are clearly seen in the photo below.

The species was described as late as 1964 by Belgian herpetologist Gaston François de Witte (1897-1980), who named it in honour of American ornithologist James Paul Chapin (1889-1964), co-leader of the Lang-Chapin expedition.

This exhausted male Chapin’s chameleon was purchased from locals by one of my companions during a car trip across Zaire, between Gemena and Lisala, December 1980. Obviously, it had not been fed for several days, because it died a few hours after the purchase. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trioceros nyirit Mount Mtelo stump-nosed chameleon, Pokot chameleon

This species is known from two locations in Kenya, the Cherangani Hills and the Mtelo massif, living at elevations between 2,900 and 3,150 m.

The specific name is the word for chameleon in the Pokot language. This animal was first described from the Pokot tribal area in the Cherangani Hills.

Mount Mtelo stump-nosed chameleon, Murgogi, Cherangani Hills, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cheloniidae Sea turtles

Of the world’s 7 species of sea turtles, 6 belong to this family. These animals are characterized by having shields covering back and belly, firmly attached to vertebra and ribs. The back shield is called a carapax, the belly shield plastron. Both shields are covered in scutes, consisting of horn-like keratin. The scutes on the back are arranged in 3 longitudinal rows.

The seventh species is the huge leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which forms a separate family, Dermochelyidae. It has no scutes, but a leathery skin that covers 5 or 7 longitudinal ribs along the back.

Although sea turtles spend about 98% of their life in the oceans, the females must get ashore, when they are about to lay eggs. With a great effort, they crawl ashore on a sandy beach, where they use their hind flippers to dig a hole above the high tide line.

When a female has finished digging, she lays a number of white eggs, often between 80 and 100. They resemble table tennis balls, but are soft, so as not to break when they fall into the hole. When the egg-laying is over, the female covers the eggs, throwing sand about with her flippers to camouflage the spot. Then she returns to the sea.

Some sea turtle species lay eggs several times in a season, in some cases up to 11 clutches. It sounds incredible, but the female often returns to the beach where it hatched many years before. How she is able to do that remains a mystery. One theory is that the animals are imprinted by the physical and chemical composition of the beach, and that they are able to use the Earth magnetism to navigate from.

Earlier, adult sea turtles didn’t have many enemies. Tidligere havde voksne havskildpadder ikke mange fjender. Large sharks and orcas (Orcinus orca) may take some, although it is a rather bony mouthful. However, with the spreading of humans to the entire planet, the situation is quite different, and all eight species are declining drastically. The eggs are dug up and eaten by poor settlers, or eaten as a delicacy in restaurants, or because they are regarded as an aphrodisiac. Many adult turtles are also eaten by people.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is persecuted due to its beatiful carapace, from which jewelery, combs, and other items are carved. Numerous carapaces are imported by the Japanese. Even entire, varnished carapaces are sold as souvenirs, among other places in Indonesia.

Tens of thousands of sea turtles drown in fishing nets or become damaged by the propellors of boat engines. Young turtles die from eating waste oil and lumps of tar, floating on the surface. Many leatherbacks eat plastic, which resembles their main food, jellyfish. The plastic cannot be digested and gets stuck in the intestines, causing the animal to die from starvation.

The characteristic tractor-like tracks from an egg-laying sea turtle, Shungu Mbili Island, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Carapaces from sea turtles, which were killed and eaten by fishermen, Shungu Mbili Island. Note the barnacles on one of the carapaces. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chelonia mydas Green turtle

This species, growing to 1.5 m long, is the only member of the genus. It is widespread in tropical and subtropical waters around the world. Previously, populations along the Mexican and Central American Pacific coasts were regarded as a separate species, the black turtle (C. agassizii), but are now considered conspecific with the green turtle.

It has been much persecuted due to its delicious meat, and is now listed as endangered by the IUCN.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khelone (‘tortoise’), whereas the specific name is from the Greek mydos (‘humidity’), referring to its aquatic habitat.

Mating green turtles, near Boydu Island, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill turtle

The hawksbill turtle, the only member of the genus, is widespread in tropical and subtropical waters, living mainly at coral reefs, where its main food is sea sponges. As described above, this species is much persecuted due to its beatiful carapace, and many are also caught in fishing nets. It is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek eretmon (‘oar’) and chelys (‘tortoise’, ‘turtle’), alluding to the oarlike limbs of this species. The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘overlapping’, referring to the overlapping scutes on the carapace of juveniles and immatures.

Hawksbill turtle, caught on Kwale Island, Tanzania. This species is not eaten by the locals, but the carapace will undoubtedly end up as a souvenir at a market in Dar es Salaam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colubridae Grass snakes, keelbacks, and allies

This is the largest family of snakes, comprising over 250 genera and more than 2,100 species. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. Members of the family are non-toxic, with a few exceptions.

Dasypeltis African egg-eating snakes

These animals, comprising at least 18 species, are distributed throughout Africa, with a single species in southern Arabia. They have a unique way of feeding, eating exclusively birds’ eggs. Their jaws are extremely flexible and can be opened widely, when the animal swallows an egg. On the inside of their vertebra are protrusions, which break the eggshell, whereupon the snake absorbs all juices inside the egg, only expelling the crushed remains of the shell. When threatened, these snakes rub their scales together, producing a rasping sound that sounds like hissing.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dasys, which, strictly speaking, means ‘hairy’, but may also mean ‘shaggy’ or ‘dense’, and pelte (‘a small shield’), alluding to the rough scales.

This snake, probably a common egg-eater (D. scabra), tried to swallow an egg of three-banded courser (Rhinoptilus cinctus), but gave up. Presumably, the egg was too big. – Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Philothamnus

A genus with about 24 species, found in Africa south of the Sahara.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek philos (‘loving’) and thamnos (‘bush’), thus ‘prefers to live in shrubland’.

Philothamnus hoplogaster South-eastern green snake, green water snake

This slender, green snake (rarely olive or bronze) is widely distributed, found from eastern Zaire, Rwanda, and Kenya southwards to Namibia and South Africa, living in a variety of habitats, including forest, savanna, shrubland, and along inland wetlands, from the lowlands up to altitudes around 1,800 m. It has very large, dark eyes with a round pupil.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek hoplon (‘weapon’) and gaster (‘belly’). What it refers to is not clear. Maybe the scales on the underside are sharp.

South-eastern green snake, Ncheta Island, Bangweulu Swamps, northern Zambia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

South-eastern green snake, photographed in Nairobi Snake Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cordylidae Spiny-tailed lizards

This family of small to medium-sized lizards, also known as girdled lizards, is found in eastern and southern Africa. There are 10 genera with altogether about 68 species.

Platysaurus Flat lizards

A genus with about 17 species, all living in isolated populations on rocks, found in Zimbabwe, eastern Botswana, southern Namibia, Mozambique, and South Africa.

Males of these lizards are brilliantly coloured, whereas females are brownish or greyish with white or yellow longitudinal stripes.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek platys (‘wide’) and saurus (‘lizard’), alluding to the broad, flat back of these animals.

Platysaurus broadleyi Augrabies flat lizard, Broadley’s flat lizard

This species is restricted to rocks along the Orange River, from Augrabies National Park to Klein Pella, just west of Onseepkans, Cape Province.

It was named in honour of African herpetologist Donald George Broadley (1932-2016), who described no less than 8 genera and subgenera, and 115 species and subspecies of reptiles, new to science.

Augrabies flat lizards, Augrabies National Park, South Africa. In the top picture, the Augrabies Waterfall is seen in the background. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Platysaurus intermedius Common flat lizard

This is the most widespread species of the genus, found from Zimbabwe and Malawi southwards through eastern Botswana and Mozambique to north-eastern South Africa and Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland).

Common flat lizards, Matobo National Park, western Zimbabwe. At some point, the male in the centre picture lost its tail, and a new one is growing out. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Platysaurus ocellatus Ocellated flat lizard

This species is restricted to south-eastern Zimbabwe and adjacent areas in Mozambique.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘having small eyes’, referring to the white spots on the body of the male.

Male ocellated flat lizard, Chimanimani National Park, eastern Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Crocodylidae Crocodiles

These huge reptiles, altogether about 17 species in 3 genera, are widely distributed in tropical areas, with 3 species in Africa and western Madagascar, 9 species in Asia, New Guinea, and northern Australia, and 5 in the Americas.

Crocodylus Typical crocodiles

A genus of 13 or 14 species, distributed in warm areas across the globe. The status of the Bornean crocodile (C. raninus or C. porosus ssp. raninus), remains unclear.

The generic name is derived from krokodeilos, the Ancient Greek term for these animals.

Crocodylus niloticus Nile crocodile

This formidable predator, some specimens growing more than 5 m long and weighing over 400 kg, is able to bring down large animals like zebras and wildebeest. It is widespread throughout sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of the arid areas of the south-western part of the continent, and is also found along the west coast of Madagascar. In historic times, it was living all along the Nile River (hence its name), northwards to the river delta. In Egypt, it is now restricted to the southernmost parts, around Lake Nasser.

The largest specimens occasionally turn into dangerous man-eaters.

Basking Nile crocodile, surrounded by blacksmith lapwings (Vanellus armatus), Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Basking Nile crocodiles, Ewaso Nyiro River, Samburu National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Nile crocodile is tearing apart its prey, a white-bearded wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus ssp. mearnsi), Orangi River, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elapidae

A huge and diverse family of snakes, comprising 55 genera with about 360 species, including highly venomous groups like mambas, cobras, kraits, and sea snakes. They are characterized by their permanently erect fangs at the front of the mouth.

These snakes live in tropical and subtropical regions around the world, with terrestrial forms in Asia, Australia, Africa, and the Americas, and marine forms in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. They vary greatly in size, from the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), which may sometimes grow almost 6 m long, to the white-lipped snake (Drysdalia coronoides), which is a mere 18-20 cm long.

Dendroaspis Mambas

This genus, comprising 4 extremely venomous snakes, is found south of the Sahara. Three of the species are arboreal, whereas the black mamba (below) is mainly terrestrial.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’) and asp (‘venomous snake’).

Dendroaspis angusticeps Eastern green mamba

A highly venomous, arboreal snake, which may grow to about 2 m long. It is native to south-eastern Africa, mainly found in coastal areas in Kenya and Tanzania, and from eastern Zimbabwe southwards to the east coast of South Africa.

During field work in 1989 in Tanzanian coastal forests, my companions and I encountered green mambas on several occasions, as they lay draped over thin branches in the trees. However, they were not at all aggressive, and we could admire their beautiful colour from a distance.

The specific name is derived from the Latin angustus (‘narrow’) and –ceps (‘-headed’).

Eastern green mamba in captivity, Nairobi Snake Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dendroaspis polylepis Black mamba

Despite its name, this snake is not really black, but blackish-brown or greyish. It was probably named for the inside of its mouth, which is black. It is the second-longest snake in the world, sometimes growing to 3 m long. Only the Asian king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) is longer.

The black mamba lives in various habitats, including savanna, woodland, rocky slopes, and sometimes forest. It is the fastest snake in the world, over short distances able to attain a speed up to 16 km/h.

During field work in 1990 in Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania, we observed a black mamba on the forest floor. When we approached to have a closer look at it, it regurgitated an elephant shrew (Macroscelididae), whereupon it disappeared at a tremendous speed.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek polys (‘many’) and lepis (‘scale’).

Black mamba, Nairobi Snake Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gekkonidae True geckos

This is the largest family of geckos, containing over 950 species in 64 genera.

The name gecko stems from the call of the Southeast Asian tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), rendered as geck-oo or tuc-too.

Unidentified gecko, presumably a species of house gecko (Hemidactylus), on a house wall, Chembe, Malawi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Unidentified gecko, Gombe Stream National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chondrodactylus Thick-toed geckos

A small genus of 6 species, all but C. turneri (below) restricted to southern Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khondros (‘grain’) and daktylos (‘finger’), thus ‘having feet with a granular structure’.

Chondrodactylus turneri Turner’s thick-toed gecko

This spectacular gecko is widely distributed, found from Kenya southwards through eastern Africa to South Africa, and also in Botswana, Namibia, and Angola.

It was named in honour of British entomologist and merchant James Aspinall Turner (1797-1867).

Turner’s thick-toed gecko, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the ribbed toes of Turner’s thick-toed gecko, Matobo National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Phelsuma Day geckos

A large genus with about 55 species of diurnal geckos, most of which are green or bluish with reddish-brown markings. The vast majority are endemic to Madagascar and surrounding islands, but a few species are found along the coast of East Africa.

The genus was named in honour of Dutch physician Murk van Phelsum (1732-1779).

Phelsuma dubia Dull day gecko, Zanzibar day gecko

This species is less colourful than most other day geckos, hence its common name. It is found in Madagascar, the Comoro Islands, Tanzania, and Kenya, living in various habitats, including human habitation.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘doubtful’. Presumably, German zoologist Oskar Böttger (1844-1910), who named this animal in 1881, was in doubt whether it was a valid species or not.

Dull day gecko on a house wall, Moroni, Grande Comore, Comoro Islands. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gerrhosauridae Plated lizards

This family, comprising 7 genera with about 38 species, is native to Africa and Madagascar. They are named for the rectangular scales of many of the species.

Matobosaurus Giant plated lizards

Members of this genus of huge lizards, comprising only 2 species, were previously included in the genus Gerrhosaurus, but were moved to this newly created genus in 2013. They are restricted to rocky areas of southern Africa. They include the common giant plated lizard (below) and M. maltzahni, which is found in Namibia and extreme southern Angola.

The generic name is derived from the Ndebele word matobo, meaning ‘bald head’, referring to the Matobo Hills in southern Zimbabwe, which are characterized by rather smooth granite hills. This area is prime habitat for plated lizards.

Matobosaurus validus Common giant plated lizard

This large lizard, growing to 60 cm long, is found from extreme southern Zambia, north-eastern Botswana, and Zimbabwe southwards to north-eastern South Africa, Eswatini (Swaziland), and Mozambique. When threatened, it will jam itself into a rock crevice and inflate its body with air, making it very difficult to extricate it.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘powerful’ or ‘strong’.

Giant plated lizard, Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lacertidae True lizards

Most members of this large family, comprising 39 genera with about 360 species, are small. They are widespread in Africa and Eurasia.

This is probably a species of sandveld lizard (Nucras), possibly N. taeniolata, although that species is not supposed to occur in Palapye, Botswana, where the picture was taken. The white objects are acacia thorns. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Unidentified lizard, Msimbazi Beach, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acanthodactylus Fringe-fingered lizards

A genus with about 40 species, found in northern Africa, southern Europe, the Arabian Peninsula, and western Asia, eastwards to Afghanistan and north-western India. Most species live in dry areas.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek akantha (‘thorn’) and daktylos (‘finger’).

Acanthodactylus scutellatus Nidua fringe-fingered lizard

This species lives in desert areas of northern Africa, southwards to northern parts of Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan, in the Middle East, eastwards to Iraq, and also in northern Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

The specific name is derived from the Latin scutra (‘tray’, ‘dish’, ‘platter’) and the diminutive suffix la, thus ‘with small plates’, referring to the scales.

Nidua fringe-fingered lizard, Zaranik Protected Area, Sinai, Egypt. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ichnotropis Rough-scaled lizards

A genus of 6 species, found in the southern half of Africa.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ikhnos (‘track’, ‘footprint’) and tropis (‘the keel of a ship’).

Ichnotropis capensis Ornate rough-scaled lizard

This colourful lizard lives in southern Africa, from Angola, Zaire, and Zambia southwards to South Africa, occurring in deserts, grasslands, and shrubberies. It is very short-lived, few surviving into their second year.

The specific name refers to the Cape region of South Africa.

Ornate rough-scaled lizard, Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pelomedusidae African side-necked turtles

A family with 2 genera and about 27 species of freshwater turtles, widespread south of the Sahara, and also occuring in Yemen and Madagascar, and on São Tomé and the Seychelles (although they may have been introduced by humans to the Seychelles). They are usually encountered in rivers, lakes, and marshes, but may occasionally be observed quite far from water.

These turtles are omnivorous, mainly eating invertebrates, including insects, mollusks, and worms. However, in South Africa one species has been observed to grab and drown doves that came to a waterhole to drink. They may also feed on carrion.

Pelomedusa African helmeted turtles, African marsh terrapins

Previously, it was thought that this genus contained only one species, P. subrufa, but today many authorities accept 10 species, 9 in Africa and one in Yemen. Many of them have a very restricted range.

The generic name is derived from the Latin pelo- (‘in mud’) and medusa. In Greek mythology, three sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, were Gorgons – winged monsters with living venomous snakes on the head instead of hair. It was said that if you happened to look at any of them, you would be turned into stone.

Thus the name means ‘Medusa, living in mud’. Well, these animals often live in muddy waters, but the connection to Medusa is hard to see.

This turtle, presumably P. subrufa, was observed in Nairobi National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This one is possibly Tanzanian marsh terrapin (P. kobe), which has a much flatter shiekld than P. subrufa. It was observed quite far from water in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Psammophiidae

A family of poisonous snakes, containing 8 genera with about 55 species, distributed in Africa, Asia, and southern Europe. It was previously regarded as a subfamily of Lamprophiidae, but is now considered a separate family.

Psammophis Sand snakes, sand racers

This genus, comprising about 33 species, is widely distributed in Africa and Asia. These snakes are diurnal, hunting for mainly lizards and rodents. All members are poisonous, but the venom is not dangerous to humans.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek psammos (‘sand’) and phis (‘snake’), thus ‘sand-loving snakes’.

Psammophis punctulatus Speckled sand racer, speckled sand snake

This beautiful snake is widespread in eastern Africa, found from southern Sudan, northern Ethiopia, and Eritrea southwards through Somalia, Kenya, and Uganda to northern Tanzania.

The specific name refers to numerous black dots along the side of the body.

Speckled sand racer, photographed in Nairobi Snake Park, Kenya. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scincidae Skinks

A huge, almost worldwide family, counting about 1,500 species of small to medium-sized lizards, many with smooth and shiny scales.

The family and common names are adapted from the Ancient Syriac word for these animals, sqinqur.

Trachylepis Striped skinks

A large genus of about 90 species, primarily distributed in Africa. One species, T. atlantica, is found on the Brazilian island of Fernando de Noronha. Its ancestors presumably drifted across the Atlantic on a floating tree, sometime during the last 9 million years. Two other species of the genus may also occur on mainland South America, but they are poorly known.

Members of the genus were formerly included in the genera Mabuya and Euprepis.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek trakhys (‘rough’) and lepis (‘scale’), alluding to 3 or more slight longitudinal keels on the dorsal scales.

Trachylepis margaritifera Rainbow skink

This colourful species is found in montane areas of southern Kenya and Tanzania, and thence southwards through eastern Africa to eastern Botswana, north-eastern South Africa, and western Mozambique.

Adult males and females are very different in colouration. Females have a dark back with 3 longitudinal white stripes and a bright blue tail, whereas males are greyish or brownish with a reddish head and tail.

It was formerly considered a subspecies of the five-lined mabuya (below), but was elevated to a separate species in 1998.

The specific name is derived from the Latin margarita (‘pearl’) and fer (‘bearing’).

Female rainbow skink, Otter Point, Lake Malawi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rainbow skink from Otter Point may be a young male, as the tail is reddish. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachylepis quinquetaeniata Five-lined mabuya, rainbow mabuya

A colourful species with a blue, reddish or brownish tail, basic colour usually olive-brown or dark brown, sometimes with pearly whitish spots and 5 white stripes on the back and sides. These stripes often fade and become indistinct in the adults. Some animals have a bright yellow line from the mouth to the forelegs, bordered by black with white dots (see picture below).

It is widely distributed, found from northern Africa southwards to Zaire and Tanzania.

The specific name is derived from the Latin quinque (‘five’) and taeniatus (‘banded’).

Five-lined mabuya, Boali Waterfalls, Central African Republic. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachylepis striata African striped skink

This skink is quite variable, but usually has a dark back, bordered on each side by a white or yellowish stripe, dark sides, and a pale belly. It is found from Central Africa and Sudan southwards to South Africa, and also on the Comoro Islands.

African striped skink, Chirindi Forest, Zimbabwe. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Trachylepis wahlbergii Wahlberg’s striped skink

This species, previously regarded as a subspecies of T. striata, is distributed in Namibia, extreme southern Angola, northern Botswana, north-western Zimbabwe, and extreme southern Zambia.

The specific name was applied in honour of Swedish naturalist and explorer Johan August Wahlberg (1810-1856), who travelled in southern Africa between 1838 and 1856, sending thousands of specimens back to Sweden. He was exploring the Okavango area in Botswana, when he was killed by a wounded elephant.

Wahlberg’s striped skink, Zambezi River, southern Zambia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Testudinidae Tortoises

Tortoises, comprising about 18 genera with around 50 living species, are distributed on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. They vary greatly in size, from the famous Galapagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger), which grows to more than 1.5 m long and weighs up to 400 kilos, to dwarves with a length of less than 10 cm.

Aldabrachelys gigantea Aldabra giant tortoise

This gigantic tortoise is the second-largest tortoise species, males growing to about 1.2 m long and weighing up to 250 kg, females generally smaller, about 90 cm long and weighing up to 160 kg. It is the only living member of the genus, distributed on a number of islands in the Seychelles. Two other members, which were found in Madagascar, have gone extinct.

The generic name is composed of Aldabra, and the Ancient Greek word for tortoise, khelys.

In historic times, giant tortoises were found on many of the western Indian Ocean islands, as well as in Madagascar, and fossil records indicate that giant tortoises once occurred on all continents, except Australia and Antarctica. Many of the Indian Ocean species were driven to extinction by European sailors, for whom they were a source of food, and they seemed to be all extinct by 1840, except the Aldabra giant tortoise.

The Aldabra giant tortoise, ssp. gigantea, is endemic to Aldabra Island. This captive specimen at Lake Baringo, Kenya, is eating grass. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise

This small tortoise, males growing to 25 cm long, females to 20 cm, is the only member of the genus. It is restricted to a broad coastal belt, from central Southern Africa northwards to central Namibia.

The generic name is a classical Greek word for tortoise, whereas the specific name refers to the shape of the throat shield, which is used when males fight during mating season, attempting to overturn each other.

Angulate tortoise, Hopefield, South Africa. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kinixys Hinged tortoises

This genus, comprising 8 species, is distributed most of sub-Saharan Africa, from the Sahel zone southwards to South Africa. Several of the species are threatened.

The popular name refers to a band of flexible tissue, forming a hinge in the rear part of the shield of these tortoises, which, when closed, protects the rear legs and tail from predators.

Kinixys belliana Bell’s hinged tortoise

This northern species is distributed from the Central African Republic, Eritrea, and Ethiopia southwards to Tanzania and Angola.

The specific and common names were given in honour of English naturalist and dental surgeon Thomas Hornsey Bell (1792-1880), who became professor of zoology at King’s College in 1834.

When the famous English naturalist Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) returned to England after participating in an expedition around the world on board the HMS Beagle 1831-1836, Bell was given the task of describing the reptiles and crustacean, which had been collected during the voyage.

His works include:

A Monograph of the Testudinata, 1832-1836, which summarizes all the world’s turtles, living and extinct.

A History of British Quadrupeds, 1836.

A History of the British Stalk-eyed Crustacea, 1844-1853.

Young specimen of Bell’s hinged tortoise, Rondo Forest, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kinixys spekii Speke’s hinged tortoise

This southern species has a wide distribution, found from Zaire, Rwanda, and Kenya southwards to South Africa and Eswatini (Swaziland).

The specific and common names were given in honour of English officer and explorer John Hanning Speke (1827-1864), who explored eastern Africa on three expeditions. He attempted to find the source of the Nile, and was the first European to reach Lake Victoria.

Speke’s hinged tortoise, Tunduru, southern Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stigmochelys pardalis Leopard tortoise

Previously, this tortoise was placed in the genus Geochelone, but today that genus contains only two Asian species, and the leopard tortoise is now considered the only member of the genus Stigmochelys.

It is widely distributed in eastern and southern Africa, found from southern Sudan, Ethiopia, and Zaire southwards to South Africa and Eswatini (Swaziland). Its prime habitats are savanna and shrublands.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek stigma (‘spot’) and chelys (‘tortoise’), the specific name from the Greek pardus (‘mottled’), both names alluding to the densely spotted shield. The common name also refers to the pattern on the shield, which, with a bit of imagination, resembles the pattern on a leopard’s coat.

Leopard tortoise, Tarangire National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leopard tortoise, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Testudo Mediterranean tortoises

This genus, counting 5 species, is found in southern Europe, northern Africa, and Asia, eastwards to Xinjiang and Pakistan. Several species are threatened in the wild, mainly from habitat destruction.

They range in length from 7 to 35 cm, weighing between 0.7 and 7 kilos.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for tortoises, derived from testa (‘shell’ or ‘covering’).

Testudo kleinmanni Egyptian tortoise

This critically endangered species is native to northern Egypt, northern Libya, and southern Israel and Palestine. Previously, it was more widespread, but its numbers have dwindled alarmingly, and it may soon become extinct in the wild, unless actions are taken to protect it.

The specific name was given in honour of French banker and naturalist Edouard Kleinmann (1832-1901), who collected the type specimen in 1875.

I encountered this species in Egypt in 1999, when my late friend Uffe Gjøl Sørensen and I visited the renowned herpetologist Sherif Baha el Din (born 1960) in Cairo. He took us to the Zaranik Protected Area, where he had marked several Egyptian tortoises with chips for radio-tracking.

Egyptian tortoise, marked with a chip, glued on to its carapace for radio tracking, Zaranik Protected Area, Sinai, Egypt. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

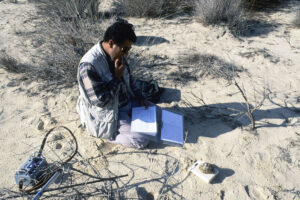

Sherif Baha el Din, weighing one of his marked Egyptian tortoises, Zaranik Protected Area. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varanidae Monitor lizards

This family is a group of about 85 species of large, carnivorous and frugivorous lizards of the genus Varanus, native to Africa, Asia, and Australia.

The family name is of Semitic origin, meaning ‘dragon’ or ‘lizard beast’. The English name is explained in various ways. Some say it has its origin due to the occasional habit of these animals to stand on their two hind legs, seemingly ‘monitoring’ something. Others say that it arose from an old superstitious belief that they would warn people of the approach of venomous animals.

My experience with the famous Komodo dragon (V. komodoensis) is related on the page Travel episodes – Indonesia 1985: Difficult journey to Komodo.

Previously, the earless monitor lizard (Lanthanotus borneensis) was placed in this family, but has since been moved to a separate family, Lanthanotidae.

Varanus albigularis White-throated monitor, rock monitor

This species, divided into 3 subspecies, is widespread in Africa south of the Sahara, found from Zaire, Uganda, southern Ethiopia and southern Somalia southwards to South Africa and Eswatini (Swaziland). It is rather large, weighing up to 17 kg. It lives in open, dry habitats, but avoids harsh desert areas.

The specific name is derived from the Latin albus (‘white’) and gula (‘throat’).

This eastern white-throated rock monitor, ssp. microstictus, allows ants to crawl on its face, perhaps to get rid of annoying pests, Tunduru, southern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varanus exanthematicus Savanna monitor

This stockily built monitor, which has a large head and a rather short tail, is widespread in open habitats south of the Sahara, found from Mauritania, Mali, Chad, and Sudan southwards to Zaire and Zimbabwe.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek exanthema, from ex-, which forms the genitive, anthos (‘flower’), and –ticus, a suffix forming adjectives, thus ‘flower-like’, presumably alluding to the pattern on the body.

Savanna monitor, Nairobi Snake Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Varanus niloticus Nile monitor

A variable and widespread species, found in almost every country in Africa, from Mauritania, Chad, and Egypt southwards to Namibia, South Africa, and Eswatini (Swaziland), living in a variety of habitats. It is the largest African monitor, weighing up to 20 kilos.

In some areas, it has become extinct locally due to over-exploitation for the skin industry.

A feral population has been established at several locations in Florida, formed from escaped or released pets. It poses a threat to the local fauna.

Nile monitors on termite mounds, Lake Manyara National Park, Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Nile monitor is basking on a tree trunk, Lake Manyara National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A monitor’s sense of smell is situated in its blue tongue. – Nile monitor, Lake Manyara National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Swimming Nile monitor, Lake Awassa, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Young Nile monitor, basking on a termite mound, Buffalo Springs National Park, Kenya. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Viperidae Vipers, adders, rattlesnakes

A huge, worldwide family of poisonous snakes, comprising 3 subfamilies, the true or pitless vipers (Viperinae) with 13 genera and about 90 species, the pit vipers (Crotalinae) with 22 genera and about 250 species, and Fea’s vipers (Azemiopinae) with one genus and 2 species.

The family name is the classical Latin word for vipers. The Latin name of the pit vipers, Crotalinae, is derived from Ancient Greek krotalon (‘castanet’), alluding to the rattle on a rattlesnake’s tail. This subfamily is found in Asia and the Americas. The members, which include rattlesnakes, lanceheads, and Asian pit vipers, are distinguished by the presence of a heat-sensing pit organ, located between the eye and the nostril on both sides of the head.

Bitis African adders

A genus with about 18 species, found in Africa and southern Arabia. All are poisonous, and some species are extremely dangerous to humans, having a fatal bite.

Bitis gabonica Gaboon viper

This extremely poisonous adder lives in forests and savannas south of the Sahara, occurring from Nigeria, Chad, and South Sudan southwards to South Africa. It has the longest fangs of any venomous snake, up to 5 cm long.

The specific and common names refer to Gabon, an area in Equatorial West Africa, named Gabão by the Portuguese, which was originally much larger than the present-day country of Gabon.

The diamond pattern down the back of the Gaboon viper is very beautiful. This one was encountered on a sandy road in Rondo Forest, southern Tanzania. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded August 2023)