Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

India 1986: “His name is Muhammed!”

The story behind the creation of this famous wetland is related on the page Travel episodes – India 1979: Hunting blackbuck with camera.

On day-long trips, on foot or bicycle, we are overwhelmed by the rich and varied bird life in this fantastic wetland. Thousands of geese and ducks, and many types of waders and eagles, spend the winter here. Among resident birds we observe painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), black-headed ibis (Threskiornis melanocephalus), oriental darter (Anhinga melanogaster), bronze-winged jacana (Metopidius indicus), various cormorants, herons, and owls, and numerous species of passerines.

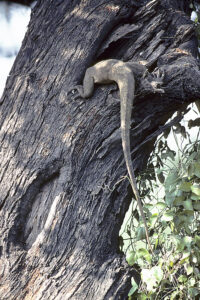

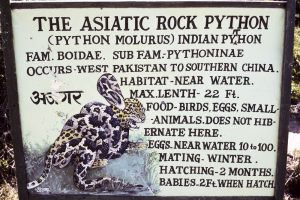

Mammals and reptiles are also found here. There is an abundance of spotted deer (Axis axis), sambar deer (Cervus unicolor), and nilgai antelope (Boselaphus tragocamelus), and we also observe smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata), turtles, Bengal monitor lizard (Varanus benghalensis), and the huge rock python (Python molurus), which may grow to a length of 5 m.

We often encounter a large nilgai bull, which has been reared in captivity and afterwards released in the sanctuary. It shows no fear at all of humans, which can cause problems. One day, when I am busy watching birds from the edge of a swamp, the bull approaches me to say hello. Foolishly, I pat it on the head – probably the last place to do so. At any rate, it seems to regard me as a rival, kneeling down on its front legs to spar with its horns. I get scared and want to back away, but my camera strap gets entangled in its horns, and I am helplessly stuck. God knows, what might have happened, if not an Indian tourist, passing by at this moment, had been able to disentangle the strap from the horns.

Between 600 and 1500 A.D., Rajasthan – in those days called Rajputana – was divided among numerous rivalling Hindu kingdoms, ruled by Rajputs (‘Sons of Rajas’). They managed to persuade Brahmins (Hindu priests) to produce genealogical tables, which connected them with the sun, the moon, and the Hindu god of fire, Agni.

These people were born warriors, divided into 36 royal clans. Because of their internal rivalries, each Rajput king ordered his people to build forts and other strongholds to protect himself and his nobles against enemies. Naturally, nobody worried about the safety of the common people.

However, when the Muslim Moghuls conquered Delhi, the glorious period of the Rajputs came to an end. Emperor Akbar, who ruled between 1556 and 1605, was a wise sovereign, who showed a great deal of religious tolerance. He managed to persuade many of his advisors to marry Rajput princesses, hereby making many of the Rajput kings become his firm allies, instead of being powerful enemies.

The power of the Moghuls weakened during the 18th Century, and the Rajputs quickly regained their former independence. In 1757, the British commenced their colonization of India by conquering Bengal, in the northeast, from where their influence spread west and south.

British forces had a very hard time subduing the Rajputs, and throughout the British colonial period they retained a great deal of power within their kingdoms. In 1948, the year after India had obtained her independence, most of the Rajput kingdoms were united into one state, Rajasthan (’Land of Rajas’), and a few years later, the remaining kingdoms joined the new state. Soon Rajasthan joined the Indian Union, and today the formerly glorious Rajputs have no political power at all.

Rajputs soon took control of the fort again, but it was conquered yet another time by Akbar’s army in 1569, after a 40-day besiege. Later, the Moghuls handed over the fort to the Maharaja of Jaipur, who kept the surrounding forests as his private hunting area. The fort was abandoned and soon fell into decay.

In 1961, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip went on a hunting trip around Ranthambhor – probably an important reason why the area in 1972 was included as one of the reserves of ‘Project Tiger’. This project was launched to rescue the Indian population of the mighty Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris), which until then had been ruthlessly persecuted. From an estimated number of 40,000, around 1900, the entire Indian population had plummeted to a mere 2,500 by 1972.

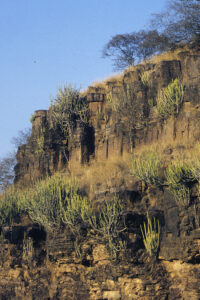

Later, Ranthambhor Sanctuary was declared a national park, and the protected area was enlarged to cover c. 500 km2. The landscape consists of low mountains, covered in shrub forest and cactus-like spurges, deep ravines with evergreen trees, and plains, covered in silvery-headed grasses. Numerous ruins are a testimony to its glorious past, as are several waterholes, constructed by the Rajputs as water reservoirs.

This park is home to an overwhelming number of animals, including spotted deer, sambar deer, nilgai antelope, Gujarat gazelle (Gazella bennettii ssp. christii), leopard (Panthera pardus), wildboar (Sus scrofa), Bengal monitor, marsh crocodile (Crocodylus palustris), and many others. There is a population of no less than 40 tigers, and – what is more interesting – they are active during the day, which naturally increases our chance of observing them.

Meanwhile, we climb the steep trail up to the old fort, from where we have an excellent view over the former maharaja’s palace, Yogi Mahal, and a beautiful lake, where large swamp crocodiles lie on the shore, jaws wide open. Two hours later, we are back at the entrance. Still no tracker is available, but since the staff has promised us that we could enter at this time, they allow us to enter without a tracker.

For three hours we drive around in the park. Obviously, our driver doesn’t possess much knowledge of the art of wildlife watching. Rather, his passion seems to be racing. Several times we ask him to slow down, but it seems that he is not able to control his inclination. He is willing enough to stop when we ask him to, but his speed is so high that, invariably, whenever we come to a stop we are enveloped in a cloud of dust.

Despite our driver’s behaviour, we observe lots of mammals and birds. In the trees, troops of northern plains langurs (Semnopithecus entellus) jump about. As they are quite picky feeders, they drop more than they eat, and the ground beneath the trees is full of green twigs, to the benefit of grazing spotted deer and nilgai.

On the grass plains, we encounter wildboar, gazelles, and scores of peacocks (Pavo cristatus), and in the lakes, sambar deer walk about, eating water plants, taking no notice of the large crocodiles. It does happen that a large crocodile will grab a calf, pulling it beneath the surface to drown it. It is then tucked away somewhere to rot, until the meat is easier to tear from the bones.

During an earlier visit to India, Mr. Fateh Singh, Chief Wildlife Warden of Keoladeo Ghana, told me that tigers often come to the waterholes in Ranthambhor to kill sambar, and on several occasions, he has seen tigers steal prey from large crocodiles.

We are not that lucky. In fact, we see no tigers at all. However, today is a Sunday, and traffic around the waterholes is heavy. We decide to give it another try the following morning.

We leave the park, but soon the same problem occurs. This time, the driver’s pumping is in vain, but, as we only have to negotiate a small hill, before going downhill, he requests us to push the jeep. We struggle with the heavy vehicle, while the driver shouts: “Push! Push!” Finally, when we reach the top of the hill, we enjoy a well-deserved rest.

We proceed, zooming downhill, but haven’t gone far, before the car again comes to a stop. We shall have to disembark and push again. The driver becomes more and more agitated, shouting his: “Push! Push!”

It seems that this is one of the few English words he commands – but we must admit that in this situation it is rather relevant. The jeep jumps like a rabbit a couple of times, ignites, drives a couple of hundred metres, and then comes to a complete stop again.

By now, we are utterly exhausted, and when the driver wants us to push the car up a particularly steep hill, we refuse, making it clear to him that we intend to walk the 10 km back to Sawai Madhopur, even though the Moon is new, and it is dark as in the grave. We instruct him to walk back to Yogi Mahal to get help from the staff there, whereupon we commence walking down the road.

The darkness is so intense that we cannot see the blackish asphalt in front of us, but if we encounter soft grass we know that we are not on the road anymore. The driver has decided to follow us. Behind us, we hear his fine patent-leather shoes on the asphalt: “Clop! Clop! Clop!” Then suddenly the sound ceases. We continue in silence.

A couple of minutes later, I say: “What happened to him?”

“Yes,” someone answers from the dark, “I’ve been wondering the same thing!”

“Yes,” the others chime in.

“After all, we are in tiger land!” I say.

My companions make no comment to this, and we continue our journey. Nobody feels the slightest inclination to go back to find out what has happened to our driver.

We agree that if a car is heading for Sawai Madhopur, we are going to block the road, forcing the car to stop. Finally, we hear the welcome sound of an engine behind us, and we spread out, blocking the road. A jeep moves towards us, slows down and comes to a complete stop. Who disembarks? None other than our driver! After all, he has not been abducted by a tiger!

With a huge smile on his face (the only one we have seen all day) he explains, in Hindi, supplemented by sign language, that the petrol pump was full of dirt, and that he has sucked it out.

“Well done!” we say (in Danish), wondering why on Earth he didn’t think of that earlier.

“Yes-yes,” he says, smiling, but apart from that he does absolutely nothing.

“Ask him!” I say once more.

“Yes-yes,” he answers, again smiling widely.

I repeat four or five times, but each time he just smiles, obviously not understanding a word of what I’m saying. I get more and more desperate, but then, finally, it seems to penetrate. However, he doesn’t get an opportunity to speak to the driver. While he has been digesting my instructions, I have handed our driver 250 Rupees, the sum we agreed to pay for the jeep rent. However, he is not at all satisfied, babbling about one o’clock, long time, and the like. Despite his long speech, he doesn’t succeed in getting more money out of us.

Another driver, who has overheard our ‘conversation’, approaches us. He speaks some English, offering to drive for us the following morning. I proceed to negotiate with him.

“His name is Muhammed!” interrupts the young receptionist, smiling all over his face, filled with pleasure that he has been able to convey this important piece of information to me.

“Is that so,” I say. “I’m pleased to hear that.”

I resume my negotiations with Muhammed, arguing about the price, when the receptionist once again, with a huge smile on his face, interrupts us, saying: “His name is Muhammed!”

I give him a deadly look, and, finally, we are allowed to complete our negotiations. Behind us, my four friends are rolling with laughter.

As time goes by, he points less, instead spending his energy talking to the driver. Then a striking silence prevails on the front seat. I bend forward to have a closer look – the tracker is slumbering peacefully! At this time, not much activity is taking place around us, so we let him sleep.

Later, he awakes, returning to his old self. We are soon going to leave the park, and he doesn’t want to miss his tip. Naturally, he gets one.