Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Philippines 1984: Shamanism among Ifugao tribals

Previously, these mountain tribes were animists and head hunters, who believed that they would gain power from their slain enemies by cutting off their heads and keeping them as trophies. Their houses were built on stilts, entered on ladders, which were cut out of tree trunks. These ladders were pulled up at night, making it difficult for enemies to get into the houses and take heads. – You may read more about animism on the page Religion: Animism.

In 1898, following the Spanish-American War, the Treaty of Paris ceded the islands to the United States, after which they were known as the Philippines. Gradually, the highland tribes became more civilized, and shortly after 1950 the majority had been converted to Christianity. However, even today, many tribals still believe in the old spirits, making offerings to them, as well as to various ancient gods.

At least 2,000 years ago, these tribal people constructed fantastic terraced fields, irrigated through an advanced system of canals. On these terraces, they grow their main staple, rice, supplied with sweet potatoes, taro, and various vegetables. They also raise chickens and black pigs, and the men hunt wild animals in the jungle.

Joseph decided to ask the local medicine men for advice. Using the ‘egg test’, they suggested several options for a cure. They put an egg on top of another egg, and if it didn’t stay there, the proposed option was no good. The egg kept rolling down, until one of the men suggested calling five shamans to the village to perform a ceremony, luring the evil spirit out of old Blas’ body. This time, the egg stayed on top of the other one.

Old Blas asked the five shamans to perform a healing ceremony and brought them out to the field, where the spirit had entered his body. In this field, the shamans spent all night, making sacrifices to the spirits.

A large basket occupies the centre of the floor, containing several rice sheaves, a bowl of rice wine, a bamboo flute, and a bit of dried animal hide. There is also a larger bowl of wine, and Joseph has bought a bottle of gin and seven or eight bottles of beer for the medicine men.

“The old guys drink a lot,” he says, laughing.

The medicine men start chanting, consuming large quantities of rice wine. We are instructed not to leave the hut during this chanting. Meanwhile, a large pig has been caught and tethered to a bamboo pole, its legs tied together.

Inside the hut, two of the medicine men start dancing, one of them grasping a rice sheaf and a pig’s tail. They chant, slapping their thighs and stamping on the floor with their bare feet. The oldest one, tiny and incredibly wrinkled, gets up to deliver a long speech, the purpose of which is to call upon the evil spirit.

Joseph explains that the ritual slaughtering of the pig has to be performed slowly, because its screams will convince the evil spirit that the offering is meant for him, causing him to leave old Blas’ body. It is imperative that the blood of the pig stays inside its body, as the blood is the most important part of the offering. Using a sharp knife, one of the medicine men penetrates the pig’s skin at the lungs. He then thrusts a sharpened bamboo stick deep into its lungs, twisting it several times. The pig screams horribly, pink foam bubbling out of its mouth. After a few minutes it becomes silent, kicks a couple of times, and dies of suffocation.

The medicine men enter the hut again, and the pig is handed up to them. After a couple of minutes of dancing and chanting, the pig is taken out again. Its fur is singed in a fire, the remaining hairs are scraped off with a knife. We are again allowed into the hut, but Jette has had enough and stays outside.

The shamans now cut up the pig, and all the blood is collected for the spirit. The guts are removed, and liver and gall bladder are closely inspected. The gall bladder looks excellent, making the medicine men laugh, relieved. This is a sign that the evil spirit has accepted the pig blood and has left old Blas’ body.

The pork is divided into 31 parts, one for each family in the village. The ribs and intestines belong to the medicine men.

Outside, the young men have slaughtered a smaller pig, which is also handed up to the shamans. They cut it open, and this one, too, has been accepted by the spirit.

Two live chickens are now handed to the medicine men. For a long time, they hold them in their hands, chanting. One of the men then pulls out the neck feathers of the chickens, and a wing feather from one of them. With the pointed end of the wing feather, he pierces the neck artery of the chickens and collects the blood in a small bowl. The evil spirit will move from the sick man into this bowl. The dead birds are handed back to the young men, who will cook them.

Inside the hut, we are served our share of the pork and chickens, with a bowl of rice. My share is a piece of burned pig skin, with a few hairs and a bit of fat attached to it. I eat a tiny bit, giving the rest to a village dog which has somehow been able to climb the ladder, looking for goodies. One of the shamans notices the dog, immediately landing it a precise kick right under the chin, causing it to roll backwards down the ladder, howling in pain and fear.

The rest of the meat has been distributed among all inhabitants of the village. This marks the end of the healing ceremony. I hand Joseph’s mother 20 Pesos, as a contribution to the medicine men’s salary.

However, Joseph requests that we postpone the trip for a day. On our walk we are going to pass the field, in which the shamans spent the night. If Joseph passes this particular field today, the healing ceremony has been in vain. We readily agree to this, spending the rest of the day talking to Joseph in his house.

“Would you like to see my grandparents?” he asks. Naturally, we would like to meet them. He disappears into a small hut, returning with two bundles, wrapped in beautiful cloth, under his arms.

“This is my grandfather,” he says, knocking on one of the bundles.

“Tok-tok,” it rings. Very carefully, he opens the cloth, revealing a collection of human bones.

When an Ifugao has passed away, the body of the deceased is placed in a chair for a few days, watched over by a guard. If the deceased has siblings, he or she will be carried to their home and displayed there. Following a big party, the body is buried.

Two or three years later, the bones are retrieved and cleaned, wrapped in cloth, and kept inside the house. This event is celebrated with another big party, during which water buffaloes, pigs, and chickens are slaughtered. If you can afford it, another party may take place a few years later.

The bones must be treated with due respect, otherwise the deceased person will be annoyed and may cause disease in the family. The bones are kept for many generations, until nobody can remember who they are. They are then thrown away.

We now enter secondary forest, bearing the imprint of ax and fire. Two men are busy rolling a tree trunk out from a clearing, intended for growing sweet potatoes and other crops. Blue-headed fantail flycatchers (Rhipidura cyaniceps) are calling from the thickets. Joseph informs us that if one of them crosses the path in front of us, we shall have to return to the village. Luckily, they stay inside the bushes.

The path up the mountain slope is steep, and the forest gradually becomes denser. A number of orchids grow here. Joseph is quite an encyclopedia, as far as useful forest plants are concerned. The fruits of Melastoma bushes have a strawberry-like taste. The marrow from a small palm species can be eaten raw. The juice from a certain species of grass can stop bleeding. The heart-wood of a particular tree is so hard that termites avoid it, and for this reason it is very valuable for house construction, and for making rice mortars.

The trail now follows a ridge. Clouds descend on us, and it rains for some time, before the cloud cover lifts again. Often, we must stop to pull off leeches, which have attached themselves to our naked legs. Joseph’s dog is much bothered by them, bleeding in several places.

Almost hidden in the dense grass are local gods, carved from fern roots. Joseph explains that people from Cambulo always pass this place at a distance – otherwise they will cough blood.

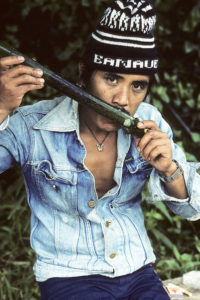

Joseph has brought his shotgun, and when an eagle takes off in front of us, he makes an attempt to shoot it. Fortunately, some branches are in the way. A large pigeon is sitting nearby, eating fruits, but Joseph is not willing to sacrifice an expensive cartridge on a small bird like that. He only shoots larger animals like bearded pigs (Sus barbatus) and deer – and the harmful eagles which eat chickens.

We reach the far end of the ridge, and then start our descent. It’s been raining a lot the last few days, making the path slippery, and we must walk with care to avoid falling. For several hours, we cling to climbers, stopping occasionally to pull off leeches. In Joseph’s opinion we are very slow, and most of the time he is far ahead.

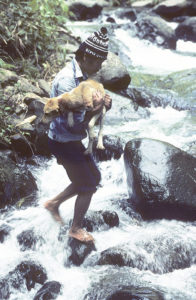

Finally, we reach the valley floor, crossing a small stream by jumping from one rock to the next. Joseph must carry his dog in his arms, as it is afraid to swim across.

The following morning, we chat with our hosts, while breakfast is being prepared. As it turns out, three young men are going to the village of Batad, further down the valley. They agree to be our guides and to carry our packs to Cambulo. We say goodbye to Joseph, who disappears up the mountain slope with his dog. He is going to do a bit of hunting on his way home.

The young men walk briskly. Following a steep descent, we walk along the levees between the rice fields. On this clear morning, the view across the valley is indeed beautiful. A couple of hours later we spot Cambulo, a large village near a river.

While I make a stop to take some photographs, Jette proceeds, and when I catch up with her, she is talking to two Western women, one of them an American missionary, named Delia. She was much surprised to see a lone European woman emerge from the rice fields. The other woman is a German tourist, whose husband is upstream, taking a bath. I join him, whereas the three women go further upstream to another bathing spot.

Delia is unmarried and has been living in Cambulo for 14 years. She confides in us that it is extremely difficult to convert these people to Christianity, and she often feels lonely. She is very happy to see us and invites all four of us to stay in her house.

When she learns that Jette is a physiotherapist, she is overjoyed, imploring her to treat some of the village women who are suffering from headache and muscle pain.

We stay in her house for a few days. She has a tame monkey, a young long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis), which was given to her by a hunter who shot its mother. It’s quite cute, but also naughty, especially at mealtime. – You may read more about this species, as well as many other monkeys, on the page Animals: Monkeys and apes.

Jette is working hard, trying to help the women. She confides in me that she has rarely encountered such damage in people. The women are simply worn out by hard work, and all she can do is to give them a massage to lessen their pain. Delia explains that the men are lazy. While the women are doing all the hard work, they collect firewood in the forest, go hunting, and look after the children.

Accompanied by several children, I stroll in the neighbourhood. The kids spot a snake in a bush, but even though they point it out to me, I am simply not able to see it. They show me a small plant, whose leaves contain a lot of vitamin C, and we encounter birds like Philippine coucal (Centropus viridis), long-tailed shrike (Lanius schach), and grey wagtail (Motacilla cinerea).

In the evening, hundreds of fireflies are gathered in a thicket. Their flashing is so bright that the bushes are illuminated.

We encounter a couple of school girls who climb a tree to collect its edible fruits, breaking off a branch and handing it to us. The berries are sweet and sticky.

Gradually, the trail widens, and, as it turns out, a road is under construction between Banawe and Cambulo. Delia told us that this construction had lasted six or seven years, and the road would probably never be completed. We meet only five or six road workers, scraping a bit with a shovel here and there – no machines. Very good, we think, this means that Cambulo will have peace for some years to come. Five or six kilometres before Banawe, we get a lift with a jeep.

We make a visit to Joseph in Bocos, as we would like to hear how his father is doing. As it turns out, he was cured by the shamans. The day after the ceremony he was moving about, and a few days later, he guided some tourists across the mountain range to Cambulo.