Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

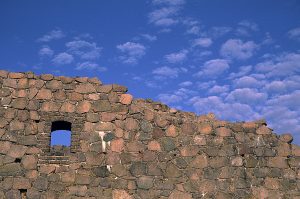

Hammershus – largest ruin in northern Europe

In 1265, Hammershus was conquered by King Erik Klipping, who handed it back to the archbishop in 1276, and during the reign of two later archbishops, Jens Grand and Esger Juul, the castle played an important role in the power struggle between King and Church.

The masons then decided to start building on another hill nearby, and this time the ’subterraneans’ approved of the site – so much that they began to help building. Every morning, when the masons returned to the construction site, the wall had, mysteriously, become higher during the night. The builders put out sentries to find out what was going on, but, invariably, they fell asleep.

A very brave man now decided to keep a watch from the wall itself – with a fatal result. Next morning the masons saw that the wall had become higher during the night, but in the new part of the wall they found a piece of the night guard’s clothes – and that was all they ever saw of him again. From this day, nobody dared to interfere with the work of the ’subterraneans’, and construction of the castle was finished without further incident.

As most people in those days had very little cash, they paid their taxes in kind, i.e. crops and husbandry. On average, in a typical year, the Bornholmians delivered the following items as taxes: c. 200 tons of crops (wheat, rye, or barley), c. 20 tons of butter, 104 head of cattle, 37 pigs, 360 geese, 2,670 chickens, 3,390 loads of firewood, and a small amount in cash. Furthermore, the farmers had to work a certain number of days per year for Hammershus – without pay.

In 1361, King Valdemar Atterdag conquered Hammershus. However, to be on good terms with the strong and wealthy Church, he handed back the castle to the archbishop, on the condition that the king could always demand it to be handed back again.

The following year, Christian II was usurped by Frederik I, who received help from the Lübeckians. In return for this favour, the Lübeckians, who wanted to control the whole trade of the Baltic area, were given Bornholm as security by King Frederik for 50 years, with the right to tax the people. In return, it was their duty to protect the island against the Swedes, who were arch enemies of the Danes.

Hammershus was now rebuilt, with new walls, bridge and moat, towers, cannons, and a church. The German commander Schweder Kettingk was very popular among the Bornholmians. Not only did he rebuild the castle, he also erected small fortifications on numerous locations along the coast around the island. Throughout The Seven Year War (1563-1570), all Swedish attacks on the island were repelled. Remains of the fortifications can still be seen many places along the coast of Bornholm.

During a new Danish-Swedish war, in 1657-1658, the Swedes conquered all Danish belongings in the southern part of the Swedish peninsula, and Bornholm. The commander on the island was Johan Printzensköld, who was most unpopular, partly because of the heavy taxes, but mainly because young Bornholmians were enrolled in the Swedish army.

In 1658, Bornholmian rebels attacked the Swedish forces, and Printzensköld rode to Rønne, the main town, to call for more troops. However, he was captured and shot in Rønne. The rebels now went to Hammershus, one of them dressed in Printzensköld’s clothes. The Swedes forces, who thought that their commander had been caught by the rebels, opened the gates and surrendered without battle. From this day, Hammershus – and Bornholm – was again on Danish hands.

In 1684-1687, a new fort was built elsewhere on Bornholm, on the tiny island of Christiansø, and Hammershus lost its importance. In 1743, locals were allowed to tear down its walls for other construction, and 50,000 bricks were sold. In 1814, the demolition came to a halt, and Hammershus was made a protected monument in 1822. Restoration began in 1885.