Cacti

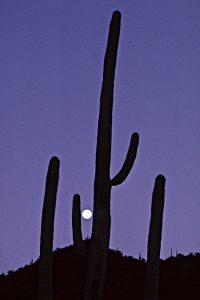

Saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) at sunset, Picacho State Park, Arizona. A large specimen may weigh up to 10 tonnes, of which 90% is water – enough for several years without precipitation. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As their name implies, the stem of barrel cacti (Ferocactus) is barrel-shaped. This picture shows red barrel cactus (F. cylindraceus), observed in Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

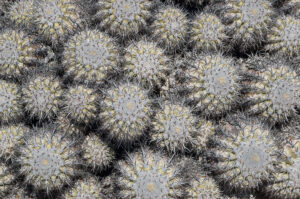

Most Copiapoa species form compact ‘cushions’ of numerous, closely clustered stems, in this caze C. malletiana, Llanos de Challe National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stem segments of prickly pear cacti (Opuntia) are broad and flat. This picture shows tulip prickly pear (O. phaeacantha), Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

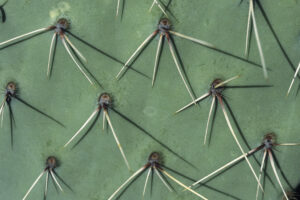

Close-up of the cylindric stem segments of buckhorn cholla (Cylindropuntia acanthocarpa), Santa Rosa Mountains, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

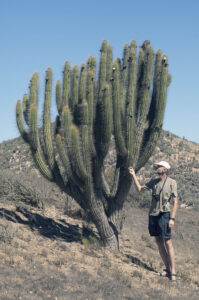

Organ pipe cactus (Stenocereus thurberi) resembles saguaro (above), but is branched from ground-level. – Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, southern Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cactus plants (Cactaceae) constitute a huge family, comprising about 127 genera and at least 1,750 species. Members of this family are succulents, storing water in the stem, which means that they are able to continue growing during periods of drought.

Shape and size of cacti vary enormously. The stem may be columnar, as in Carnegiea, Stenocereus, Eulychnia, and many other genera, barrel-shaped as in Ferocactus and Echinocactus, ball-shaped as in Copiapoa, Mammilaria, and many other genera, or low and dome-shaped as in little nipple cactus (Mammillaria heyderi) and peyote (Lophophora williamsii).

In many genera, the stem is divided into segments, which may be broad and flat as in Opuntia and Consolea, narrow and flat as in Hylocereus, Hatiora, Epiphyllum, and others, or cylindric as in Cylindropuntia, Echinocereus, and many others.

Some genera are epiphytic, including Strophocactus, Disocactus, Hatiora, and Hylocereus.

In most cacti, the leaves are reduced to spines, and photosynthesis takes place in the green stem. The spines protect the plant from being eaten, provide some shade, and bend the dry desert wind, preventing it from reaching the stem, thus reducing evaporation.

Cactus species all have small bumps on the stem, called areoles, which are also highly modified leaves. The flowers emerge from these areoles, each areole only producing one flower in its lifetime. As the plant grows, new areoles are formed.

Glochids are short spines, often hair-like, which grow in clusters from the areoles, especially on members of the sub-family Opuntioideae, which includes prickly pears, chollas, and others. When touched, these glochids easily detach and get lodged in the skin, causing immense irritation. The name is from the Greek glochinos, which may refer to any projecting point, especially of an arrow.

The word cactus is a Latinized version of the Greek kaktos, a name originally applied to an unknown spiny plant by Greek scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371-287 B.C.), called ‘the founder of botany’.

Below, a number a cacti are presented in alphabetic order, according to genus and species.

Carnegiea gigantea Saguaro

Undoubtedly, the best known cactus species is the huge saguaro (pronounced ‘sawaro’), which has provided a decorative background in countless western films, but is in fact of a rather limited distribution, growing only in the Sonoran Desert of Mexico and southern Arizona, and in a small area of adjacent California.

A saguaro begins its life as a small, black seed, which sprouts in litter at the foot of a saguaro or a tree, well protected against drought and rodents, which would happily eat it.

If the newly sprouted cactus survives its first year, it is about 5 mm high. Fifteen years later, it is app. 30 cm high, and 25-50 years old it may be as tall as 2 m. Now it will bloom for the first time. About 75 years old, it grows its first side segments, popularly called ’arms’, and about 100 years old, it may have reached a height of c. 8 m.

Reaching the ripe age of 150 years, it is the patriark of the desert, up to 12 m tall and weighing 8-10 tonnes, of which about 90% is water. Following a rain shower, the extensive root system of a large saguaro may absorb as much as 600 litres of water – enough for a year.

In May, clusters of large white flowers emerge at the tip of the ‘arms’. They open in the evening, bloom until noon the following day, and then wither. However, this is ample time for the large majority of the flowers to be pollinated by insects, birds, or leaf-nosed bats of the family Phyllostomatidae. These bats feed almost exclusively on pollen of large desert flowers.

Each of the green fruits contains up to about 2,000 seeds. The fruits open in July, revealing red, sweet pulp around the seeds. This pulp is much praised by a large variety of animals, which, by eating the pulp, spread the seeds. Previously, indigenous peoples like the Tohono O’Odham collected the fruits, making juice and jam from them.

An old saguaro produces hundreds of thousands of seeds annually, and at the age of 200 years, it may have produced up towards 40 million. Only a tiny fraction of this enormous number of seeds will sprout, and even fewer will attain old age.

In the saguaro stems, gila woodpeckers (Melanerpes uropygialis) and northern flickers (Colaptes auritus) excavate nest cavities, often several each season. However, they do not occupy one until the following year, when the soft cactus tissue has hardened to become wood.

Abandoned woodpecker cavities are taken over by numerous other animals, including rats, mice, lizards, snakes, honey bees, and a variety of birds, including purple martin (Progne subis), western kingbird (Tyrannus verticalis), and three species of owl, western screech-owl (Megascops kennicottii), ferruginous pygmy owl (Glaucidium brasilianum), and the tiny elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi), the smallest owl in the world, being no larger than a sparrow.

For unknown reasons, the saguaro has declined in the northern part of its distribution area in later years. Severe frost and overgrazing have been suggested as two possible causes.

The generic name was given in honour of Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919), a Scottish-American industrial magnate, who devoted his later years to philanthropy, with special emphasis on world peace, education, libraries, and scientific research.

Morning sun on a saguaro ‘forest’, Saguaro West National Park, Arizona. The plant with red flowers is ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens), and the shrub with yellowish bark is palo verde (Parkinsonia aculeata). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When it is about 75 years old, a saguaro grows its first side segments, popularly called ’arms’. – Saguaro West National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Saguaro and Full Moon at dusk, Saguaro West National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Morning light on saguaro ’arms’, Colossal Cave Mountain Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of saguaro open in the evening, bloom until noon the following day, and then wither. – Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A cristate, or crested, saguaro forms, when the cells in the growing stem begin to divide outward, rather than in the circular pattern of a normal cactus. This mutation results in the growth of a large fan-shaped crest at the growing tip of a saguaro’s main stem or ‘arms’. – Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dead saguaros often remain standing for years, like this ‘skeleton’ near Lake Saguaro, Phoenix, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The gila woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis) often pecks a nest cavity in an old saguaro, as here in Tucson Desert Zoo, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Saguaros often serve as perches for various birds. These pictures show white-winged dove (Zenaida asiatica), black-throated sparrow (Amphispiza bilineata), and red cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis), all photographed in Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Consolea

Members of this genus, and of the genus Opuntia (below), are characterized by their broad, flat stem segments, called cladodes. As opposed to most Opuntia species, cladodes of Consolea species grow into rounded trunks, and new cladodes evolve at the end of these trunks.

These plants, comprising 10 species, are distributed in the Caribbean and Florida. The genus was named in honour of Italian botanist Michelangelo Console (1812-1897).

Consolea rubescens

A nearly spineless cactus, growing to 6 m tall, with characteristic bumps on the flattened cladodes. This species is native to Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, and Antigua & Barbuda.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘reddish’. It may allude to the flower colour.

Consolea rubescens, Bosque del Guanica, Puerto Rico. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copiapoa

Most members of this genus, comprising about 32 species, are rather small and ball-shaped, although some are cylindrical. They are ribbed and have a woolly apex, where the yellow flowers emerge. Most are spiny, although a few species lack spines. One species, C. hypogaea, lives most of its life underground, with only the woolly apex visible. It is barely noticed, except when flowering.

This genus is restricted to northern Chile, primarily growing in the Atacama Desert, which receives almost no rain. The plants get most of the moisture from coastal fogs, which are frequent here, concentrating around 500 to 850 m altitude.

The generic name is derived from Copiapó, a region in the Atacama Desert.

Copiapoa cinerascens

Globular, to 15 cm in diameter, with 15-20 ribs, grey-green or ash-grey, with grey wool at the top. The grey colour stems from a waxy coating, which prevents the plant from drying out. The flowers are yellow. It has shorter and much darker spines than the very similar C. malletiana (below).

This species is restricted to a coastal strip in Chile, from south-west of Antofagasta to the north-western part of the Atacama Desert. Strongholds of the plant are Pan de Azucar and Llanos de Challe National Parks.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘turning to ashes’, derived from cinereus (‘ash-coloured’).

Copiapoa cinerascens, Llanos de Challe National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copiapoa cinerea

A very variable species with several subspecies and varieties. The pictures below show subspecies columna-alba, which may be identified by its columnar shape, growing to 1.2 m tall with a diameter of 10-20 cm, ribs broad, 12-30, spines black. The stems appear white, caused by a waxy coating, which prevents the plant from drying out. The flowers are yellow, to 2.5 cm across, occasionally with a pink or reddish tint.

A very drought-tolerant plant, found from sea level up to an elevation of about 500 m. It occurs in large numbers at numerous locations from Pan de Azucar National Park northwards to Taltal, making impressive stands, “resembling a marching army.” (llifle.com)

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ash-coloured’.

“Resembling a marching army.” – Copiapoa cinerea, subspecies columna-alba, Pan de Azucar National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copiapoa cinerea, subspecies columna-alba, Pan de Azucar National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copiapoa cinerea, subspecies columna-alba, at sunset, Pan de Azucar National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copiapoa malletiana

This species, also known as C. dealbata, is restricted to a limited area around Quebrada Carrizal Bajo, notably Llanos de Challe National Park, growing at altitudes between 200 and 500 m, often forming huge populations. It very much resembles C. cinarascens (above), but has much longer and often paler spines.

The specific name is derived from the Latin malleus (‘mallet’), presumably alluding to the stem shape.

Huge congregation of Copiapoa malletiana, Llanos de Challe National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of Copiapoa malletiana are pale yellow. – Llanos de Challe National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A yellow lichen grows on the trunk of this Copiapoa malletiana, Llanos de Challe National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cumulopuntia

In 1980, about 30 species were removed from the genera Opuntia and Tephrocactus to a new genus, Cumulopuntia, primarily due to the fruits, which contain no pulp, a different seed structure, and the overall growth being a compact cushion. Since then, this genus has been reduced to 20 species, and some authorities acknowledge only 5-7 species. These plants are found in central South America.

The generic name is Latin, derived from cumulus (‘heap’), presumably alluding to the densely packed stems, and the name of another cactus genus, Opuntia, which was named for the Ancient Greek city of Opus, where, according to scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371-287 B.C.), an edible plant grew, which could be propagated by rooting its leaves – just like members of this genus can be propagated by rooting their stem segments. (Source: U. Quattrocchi 2000. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names)

Cumulopuntia sphaerica

This plant, also known as C. leucophaea, forms low clumps of small, globular, green stems with numerous long spines, pale or brownish, flowers yellow or orange. It is very common, distributed from central Chile northwards to Peru, growing from near sea level to the timber line in the Andes, sometimes found at altitudes of 4,200 m.

Vernacular names of this species include gatito (‘little cat’) and perrito (‘little dog’). They must be ironic, as the plant is very spiny and not in the least cuddly.

Cumulopuntia sphaerica, encountered south of Vallenar (top) and in Valle del Encanto, near Ovalle, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia Cholla

These plants, comprising about 35 species, are native to south-western United States, Mexico, and the West Indies. They were formerly included in the genus Opuntia (below), but differ from members of that genus by their cylindric stem segments, and also by having papery sheaths on the spines.

Many species of cholla are completely covered by a dense mass of long, barbed spines. When the spines attach themselves to a furry animal or a sweater, the segments easily break off, and because of the barbs, the spines penetrate deeper into the fur or skin. When the animal or the person manages to wrench the segment from its fur or skin, it is often dumped in a new location, where it may be able to sprout – an effective way of spreading the species.

Due to the scarcity of food in early spring, this season was called ko’oak macat (‘painful moon’) by the Tohono O’Odham people of southern Arizona. During this period, they would pit-roast thousands of calcium-rich cholla flower buds, which have an asparagus-like taste. (Source: fondazioneslowfood.com)

The generic name means ‘the cylindric Opuntia‘, alluding to the cylindric stems of many of the species, and Opuntia (see Cumulopuntia above). Cholla (pronounced ‘choy-ya’) is a Mexican-Spanish word, meaning ‘skull’ or ‘head’, perhaps derived from Old French cholle (‘ball’). This term may refer to the end segments, which are often ball-shaped.

Most animals avoid chollas, but the cactus wren (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) often builds its nest among the horrible spines, where it is well protected against enemies. Pack rats of the genus Neotoma gather fallen cholla segments around their burrows as a means of defense against predators like kit fox (Vulpes macrotis) and coyote (Canis latrans). Snakes, however, are not deterred by this armour.

Singing cactus wren, Tucson Mountain Park, Arizona. This species is the largest among the wrens, about the size of a starling. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This cactus wren brings excreta of its young away from the nest, placed in a silver cholla (C. echinocarpa), Phoenix South Mountain Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia acanthocarpa Buckhorn cholla

This widespread species is distributed in southern Nevada, eastern California, Arizona, southern Utah, and extreme northern Baja California and Sonora in Mexico. It grows to 3 m tall, branches profusely, and has a rather open cover of brownish spines of uneven length.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek akanthos (‘spiny’) and karpos (‘fruit’). The common name alludes to the branches, whose shape often resemble deer antlers.

Buckhorn cholla, Cima Dome, Mohave National Preserve, California. In the lower picture, a ‘forest’ of Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) is seen in the background. This species is described on the page Plants: Plants of Sierra Nevada. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture shows the cylindric stems segments of buckhorn cholla, Mohave National Preserve. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of buckhorn cholla are various shades of yellow, orange, or red. – Mazatzal Mountains (top), Salt River (centre), and Saguaro West National Park, all in Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia arbuscula Arizona pencil cholla

This cactus is restricted to south-central Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora. Its stem segments are a little thicker than those of pencil cholla (below), up to 1.5 cm in diameter, and it has much fewer and shorter spines. The flowers are various shades of yellow.

The specific name is derived from the Latin arbor (‘tree’) and cula, a diminutive suffix, thus ‘little tree’. The common name alludes to the thin stems.

Arizona pencil cholla, Picacho State Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia bigelovii Teddybear cholla, jumping cholla

This species was named after the shape of the upper segments, which resemble the arms of a teddybear. However, should this resemblance make you hug it, you will regret it a million times: the ‘softness’ of this plant is deceptive, as it consists of a solid mass of very sharp spines. The name jumping cholla refers to the loose segments, which ‘jump’ on bypassing animals or people.

This plant is distributed from extreme southern Nevada southwards through eastern California and western Arizona to Baja California, Sonora, and Sinaloa in Mexico. It is one among many plant species named in honour of surgeon and botanist John Milton Bigelow (1804-1878), who collected many new species on expeditions to south-western U.S. and northern Mexico.

A dense stand of teddybear cholla is found in Joshua Tree National Park, California, where these pictures were taken. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Teddybear cholla and red barrel cactus (Ferocactus cylindraceus, see below), Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of teddybear cholla are green. – Joshua Tree National Park. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia echinocarpa Silver cholla

This plant, also known as golden cholla, is quite common in southern Nevada, eastern California, western Arizona, and extreme northern Baja California and Sonora in Mexico. It grows to 2 m tall, half of which may be a tree-like trunk.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’) and karpos (‘fruit’).

The barbed spines of silver cholla cling to almost anything, including the finger of my companion Lars Skipper, Tucson Mountain Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spines of silver cholla with raindrops, Tucson Mountain Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of silver cholla are mostly green or yellowish-green, but may sometimes be white, as in this picture from Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia fulgida Chainfruit cholla, jumping cholla

The name chainfruit cholla refers to the spineless fruits, which form chains, hanging down from the end of each segment. The plant may be up to 3.5 m tall, growing in scrubland and deserts, and on grassy hillsides, from south-central Arizona south to Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico. The flower colour varies from pink to violet.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘shining’, perhaps alluding to the shining thorns. The name jumping cholla refers to the loose segments, which ‘jump’ on bypassing animals or people.

A chain of pendent chainfruit cholla fruits, Saguaro West National Park, Arizona. A saguaro (see above) is seen in the background. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia ramosissima Pencil cholla

This plant is named for its thin stem segments, which have a diameter of only up to 1 cm. It is also characterized by the very long, yellowish spines, which stand out at right angles to the segments. Another distinctive feature is the diamond-shaped areoles.

Pencil cholla is native to eastern California, western Arizona, and northern Baja California.

The specific name is derived from the Latin, meaning ‘with many branches’ – a most descriptive name.

Pencil cholla, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia spinosior Cane cholla

This species is distributed in eastern Arizona and western New Mexico, southwards into the northernmost parts of the Mexican states Sonora and Chihuahua. It is quite similar to buckhorn cholla (above) and staghorn cholla (below), but may be identified by its shorter and thicker stem segments, which tend to droop downwards. It is also lower than those two species, growing to 1.2 m tall. The flower colour is highly variable, pink, red, purple, yellow, yellowish-green, or white.

The specific name is derived from the Latin spinosus (‘thorn’) and the suffix ior, thus ‘thornier’ – i.e. compared to C. whipplei.

In Australia, where this species is known as snake cactus, it is often invasive and has been declared a noxious weed.

Cane cholla, Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cylindropuntia versicolor Staghorn cholla

The spines of this species are all short, not much more than 2.5 cm, all having more or less the same length, as opposed to buckhorn cholla (above). The specific name refers to the flower colour, which may be red, yellow, or purple. It is restricted to southern Arizona and the Mexican states of Sonora and Sinaloa.

The common name alludes to the branches, whose shape often resemble deer antlers.

Staghorn cholla, Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Deamia

This epiphytic genus contains only 2 species, found tropical forests in eastern Mexico and Central America.

The generic name honours American botanist Charles Clemon Deam (1865-1953), who discovered 25 new plant species.

Deamia testudo Yucatan climbing cactus

This species, formerly known as Selenicereus testudo and Strophocactus testudo, grows to 3 m long or more, the segmented stems clinging to tree trunks or branches. It is distributed from eastern Mexico eastwards to western Panama. The flowers are white.

It lives in a symbiotic relationship with ants. The cactus provides shelter for ant colonies, which will attack any herbivore attempting to eat the plant.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘tortoise’. German botanist Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini (1797-1848) likened the stems to “a procession of dark green tortoises, walking close behind one another.”

Yucatan climbing cactus, clinging to the branches of a tree, Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Disocactus

This genus of epiphytes, comprising 16 species, is found in rainforests of southern Mexico and Central America, with a few species extending into northern South America and the Caribbean. Stems are flattened and spineless in some species, cylindrical and spiny in others.

The generic name is derived from the Greek dis (‘twice’ or ‘double’), referring to the fact that the outer and inner flower segments are of equal length.

Rainforest tree with plenty of epiphytes, including an unidentified species of Disocactus, Tikal National Park, Guatemala. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echinocereus Hedgehog cactus

This genus, comprising about 70 species of medium-sized, cylindrical cacti, is native to Mexico and southern United States. They have large, gorgeous flowers, and fruits of many species are edible.

The generic name is derived from the Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’), referring to the spines, and the Latin cereus, derived from the Greek keros (‘wax candle’). Originally, Cereus was the name of a large number of cacti, referring to the slender and columnar shape of many of these plants.

Echinocereus engelmannii Engelmann’s hedgehog cactus

A highly variable species, distributed from southern Nevada and Utah southwards through eastern California and Arizona to southern Baja California and Sonora. It is very similar to the species below, but has 2-6 central spines per areole.

The specific and common names commemorate German-American botanist George Engelmann (1809-1884), who described many plant species, especially in the Rocky Mountains and northern Mexico.

Engelmann’s hedgehog cactus, Salt River, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echinocereus fasciculatus Cockscomb hedgehog cactus

This species is very similar to the above species, and some authorities regard them as a single species. However, cockscomb usually has one principal central spine in each areole, whereas Engelmann’s has 2-6.

It is distributed in eastern Arizona, south-western New Mexico, and northern Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico.

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin fascis (‘bundle’), thus ‘a small bunch’ (of flowers).

Cockscomb hedgehog cactus, Saguaro East National Park, Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echinocereus stramineus Strawberry hedgehog cactus

Distributed from eastern New Mexico and southern Texas southwards through eastern Mexico to San Luis Potosí. The specific name is derived from the Latin stramen (‘straw’), alluding to the long, straw-coloured spines of this species.

Strawberry hedgehog cactus, Big Bend National Park, Texas. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Echinocereus triglochidiatus Mohave mound cactus, kingcup cactus, claret cup cactus

This gorgeous plant is distributed in scrubland and dry montane woodland in the Mohave and Great Basin Deserts, from south-eastern California eastwards to Colorado and western Texas, and thence southwards into northern Mexico.

The names claret cup and kingcup refer to the red, cup-shaped flowers, claret being red wine from the Bordeaux region of France. The specific name is derived from the ancient Indo-European word tri (‘three’) and the Greek glochinos, which may refer to any projecting point, especially of an arrow. Thus, the name may be translated as ‘having three sharp points’, referring to the spines, which are arranged in clusters of 3.

The scarlet flowers of claret cup cactus seem almost too delicate to survive in the harsh environment of the Mohave Desert. These pictures are from Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eriosyce

A group of mostly globose cacti, heavily armed with strong spines. There are about 55 species, native from Peru southwards to Chile and north-western Argentina.

The generic name is derived from the Greek erion (‘wool’) and syke (‘fig’), referring to the woolly fruit.

Eriosyce curvispina

A highly variable species, mostly solitary, but occasionally forming clumps, stem globular, to 20 cm across, greyish-green, with up to 24 ribs, spines stiff, greyish-brown with a darker tip, often slightly curved, up to 3 cm long. Flowers are to 5.5 cm across, colour variable, yellowish-green, yellow with reddish-brown mid-veins, or reddish.

This plant is endemic to Chile, found from Copiapó southwards to the Rio Maule, growing in rocky areas from sea level up to an elevation of about 2,400 m.

Eriosyce curvispina, south of Vallenar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eulychnia Copao

This genus, comprising 5 large species, which grow to 7 m tall, is restricted to the very barren deserts along the coast of Chile and Peru. This area receives little or no rainfall, and the plants survive from the condensation, which the heavy and frequent fogs brings ashore.

The generic name is from the Greek eu (‘good’) and lychnia (‘candelabrum’), naturally referring to the shape of these plants.

Eulychnia acida Common copao

This spectacular plant is endemic to western Chile, from Ovalle northwards to Copiapó, found in dry areas from sea level to about 1,300 m altitude. It grows to about 7 m tall, often branched from below, with ribbed and immensely spiny stems, the spines measuring up to 20 cm in length.

This species is often infested with a bright red, parasitic mistletoe, Tristerix aphylla, whose seeds are dispersed by the Chilean mockingbird (Mimus thenca). This bird eats the fruits, but will often deposit the seeds on the spines, where they sprout, the seedling growing up to 10 cm to reach the stem of the cactus.

The fruit is edible, almost naked, without wool or spines. The specific name refers to the fruit, which has a sour taste.

Common copao often forms extensive ‘forests’, here in Valle del Encanto, near Ovalle, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copao is branched from near ground-level. – Valle del Encanto. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The tip of copao ‘arms’ are often covered in yellowish spines. – Valle del Encanto. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The spines of this copao are overgrown by a yellow lichen, Valle del Encanto. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copao flowers are pink or white. – Valle del Encanto (top) and Llanos de Challe National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copao, infested with the parasitic mistletoe Tristerix aphylla, Valle del Encanto. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Eulychnia iquiquensis Iquique copao

This species is endemic to a narrow and barren Chilean coastal strip, up to an altitude of c. 1,100 m, from south of Acida southwards almost to Copiapó. This tree-like cactus is much branched from near ground-level, older stems and branches being without spines, while younger ones near the top have numerous spines.

Iquique copao is quite common in Pan de Azucar National Park, where the pictures below were taken. Due to prolonged periods of drought, some growths are dying.

The specific name refers to the coastal city of Iquique.

Iquique copao is restricted to a narrow coastal strip in northern Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Due to prolonged periods of drought, some growths of Iquique copao are dying. This guanaco (Lama guanicoe) is standing in front of a dead specimen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Near the tip of the branches on this old Iquique copao, the thorns are covered in a reddish-brown lichen species. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The tip of Iquique copao ‘arms’ are often covered in soft, yellowish spines. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Copao flowers emerge from a whisk of brownish hairs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ferocactus Barrel cactus

Young specimens of this genus, comprising about 30 species, are columnar, but with age they become barrel-shaped and ribbed. They are found in south-western United States and north-western Mexico, typically growing in areas with irregular water flow or in depressions, which are humid part of the year.

They have very shallow root systems and are easily uprooted during flash floods. Their formidable armour of spines is an adaptation, allowing the plant to move to a more favourable location. If it is uprooted during a flash flood, the hooked spines cling to other debris, and the plant is carried to an area, where water accumulates part of the year. Here it may take root.

Members of this genus are so-called myrmecophytes – plants that live in symbiotic relationship with ants. They have extrafloral nectaries above each areole, which host ant colonies. Thus, they provide the ants with food and shelter, and in turn the ants will attack any herbivore that attempts to eat the plant.

The generic name is derived from the Latin ferus (‘wild’, ‘fierce’), referring to the fearsome spines.

Ferocactus cylindraceus Red barrel cactus, California barrel cactus

This plant is native to south-eastern California, western Arizona, and northern Baja California and Sonora, up to an altitude of about 1,500 m. As its specific name implies, this species is often cylindrical, and with age, some specimens form columns to 2 m tall.

Numerous red barrel cacti in the Mohave Desert, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of red barrel cactus are yellow. – Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up of the red spines of red barrel cactus, Mohave National Preserve, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ferocactus emoryi Emory’s barrel cactus, Coville’s barrel cactus

This species is native to south-eastern Arizona, Sonora, northern Sinaloa, and southern Baja California. The flowers are red or yellow, and the straight spines are brown, reddish, or white.

The specific name commemorates William Hemsley Emory (1811-1887), a surveyor who was mapping the Texas-Mexico border. One of the common names was given in honour of American botanist Frederick Vernon Coville (1867-1937), who participated in the 1891 Death Valley Expedition.

Emory’s barrel cactus with fruits, Tucson Mountain Park, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ferocactus wislizeni Fishhook barrel cactus, Arizona barrel cactus

With age, this species may grow cylindric. As its name implies, it has hooked spines. The flowers are red or yellow. It is distributed in southern Arizona and New Mexico, extreme western Texas, and northern Sonora and Chihuahua.

The specific name was given in honour of German-American physician, explorer, and naturalist Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus (1810-1889), who participated in many expeditions in North and Central America.

Fishhook barrel cactus with fruits, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hatiora

A small genus of 6 epiphytic cacti, restricted to tropical rainforests of south-eastern Brazil, where they are declining. One species, the Easter cactus (H. gaertneri), is a very popular house plant.

These plants are characterized by the flattened stem segments, with areoles situated at the end of each segment. Some researchers claim that 3 species should be transferred to the closely related genus Schlumbergera. These two genera have long been a cause of confusion. One difference is that flowers of Schlumbergera species are clearly tubed, whereas those of Hatiora have very small or no tubes.

The genus is named for English astronomer, mathematician, and ethnographer Thomas Harriot (c. 1560-1621), also called Hariot, who is recognized for his contributions to create advanced maps for sea navigation. In 1585-1586, he travelled in ‘Virginia’, in reality along the Roanoke River in present-day North Carolina, which in those days was included in Greater Virginia. His observations are described in The Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588).

When American botanists Nathaniel Lord Britton (1859-1934) and Joseph Nelson Rose (1862-1928) erected the genus, they wanted to honour Harriot, labelling the genus Hariota, but upon learning that this name had already been used for another genus, they used the anagram Hatiora instead.

An unidentified Hatiora species with raindrops, Yunnan Province, China. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

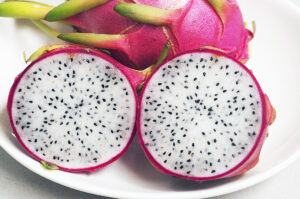

Hylocereus

This genus contains 19 species, some terrestrial, others epiphytic. They are often referred to as night-blooming cereus, which is quite confusing, as this term is also applied to many other cacti.

The generic name is derived from the Greek hyle (‘wood’), presumably referring to the stem, and the Latin cereus, derived from the Greek keros (‘wax candle’). Originally, Cereus was the name of a large number of cacti, referring to the slender and columnar shape of many of these plants.

Several species have large, sweet-tasting and delicious fruits, called dragonfruits or pitahaya – not to be confused with the word pitaya, which covers edible fruits of Mexican cacti in general. Other English names of this genus include strawberry pear, belle-of-the-night, Cinderella plant, and Jesus-in-the-cradle. In Chinese, the fruits are called 火龙果 (‘red dragon fruit’).

Mainly 3 Hylocereus species are cultivated. White-fleshed pitahaya (H. undatus) has red-skinned fruits with white flesh, red-fleshed pitahaya (H. costaricensis, also known as H. polyrhizus) has red-skinned fruits with red flesh, and yellow pitahaya (H. megalanthus) has yellow-skinned fruits with white flesh.

Stem segments of Hylocereus species are narrow and flat, and the spines are few and weak. This picture shows white-fleshed pitahaya (H. undatus), photographed in Taiwan, where this species and H. costaricensis are both commonly cultivated for their sweet, edible fruits. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Plates with white-fleshed pitahaya fruits, Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Leucostele

A genus of 13 species, almost all restricted to northern Chile, with 4 species in Bolivia and northern Argentina.

The generic name is derived from the Greek leukos (‘white’) and stele, which can be translated as ‘column’, although, strictly speaking, it means ‘a boundary post’. The name alludes to the bright white spines and the columnar stems.

Leucostele chiloensis Quisco

This columnar cactus, previously known as Echinopsis chiloensis, is common, locally abundant, in central Chile, from south of Santiago northwards to La Serena, from sea level to about 2,000 m altitude in the foothills of the Andes. It grows to about 8 m tall, branched from near the base, ribbed, and very spiny. The flowers are large and white.

Like Eulychnia acida (above), this species is a host of the parasitic mistletoe Tristerix aphylla.

Strictly speaking, the specific name means ‘from Chiloé’, an island in south-central Chile. However, in this connection, the name merely means ‘from Chile’.

Quisco, La Campana National Park, Chile. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Flowers of quisco are large and white. – La Campana National Park. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This quisco, growing south of Vallenar, Chile, is infested with the parasitic mistletoe Tristerix aphylla. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lophocereus

A small genus with only 3 species, distributed from extreme southern Arizona and Baja California southwards to western Guatemala.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek lophe (‘crest’), referring to grey bristles on the tip of the taller stems, and the Latin cereus, derived from the Greek keros (‘wax candle’). Originally, Cereus was the name of a large number of cacti, referring to the slender and columnar shape of many of these plants.

Lophocereus schottii Senita

This species, previously known as Pachycereus schottii, is native to the Mexican states Sinaloa and Sonora, the Baja California Peninsula, and extreme southern Arizona. It is branched from ground-level, usually growing to 4 m tall, sometimes to 7 m. It lives in symbiosis with the senita moth (Upiga virescens), one of the few pollinators of this plant. In return, the moth is dependent on the cactus for reproduction.

The specific name honours German artist, engineer, cartographer, botanist, ethnographer, and geologist Arthur Carl Victor Schott (1814-1875), who worked with Engelmann (see above) on the Mexican Boundary Survey.

According to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, senita is the Mexican name of this species, originally borrowed from a local tribal name of the plant, sina. Therefore, sinita would be a more correct spelling. Another popular name is old man cactus, referring to the tip of the taller stems, which are covered in grey bristles, 4-10 cm long, resembling a grey beard.

Senita, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona. The bush with yellow flowers is creosote (Larrea tridentata). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Senita has tiny, very sharp spines in the areoles. – Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mammillaria Pincushion cactus

Counting nearly 200 species, this genus is the largest of the cactus family. Most of these plants are rather small with ball-shaped stems, often growing in clumps. All have nipple-like tubercles, which have given rise to their generic name, from the Latin mammilla, diminutive of mamma (‘breast’). The name pincushion cactus refers to the formidable armour of spines, which often hides the cactus proper.

Almost all pincushion species are endemic to Mexico, a few occurring in the United States, Central America, northern South America, and the Caribbean.

Members of the rather similar genus Escobaria may be identified by their flowers, which emerge at the apex of the plant, whereas they are situated on the side of the stems in Mammillaria.

Mammillaria pottsii Rat-tail pincushion cactus

This species has a very wide range, occurring in the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, San Luis Potosí, and Zacatecas, extending into south-western Texas. It grows on hills, slopes, mesas, and flats, at elevations between 300 and 2,100 m.

The specific name honours two brothers, mining engineer Orlando Frederick Potts (1813-1855) and John Potts (1805-1876), who was director of the Chihuahua Mint in the 1830s. Both collected cactus species for English botanists.

Rat-tail pincushion cactus, Big Bend National Park, Texas. This specimen has rather dark flowers. They are usually a paler red. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Melocactus Melon cactus, Turk’s-cap cactus

This genus, comprising about 35 species, occurs in the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America, and northern and central South America.

When young, members of the genus resemble many other cacti, having globular, green stems with multiple ribs. But at maturity, they develop a cephalium, a dense mass of areoles, which form a ‘head’ directly on top of the stem. Once this cap is formed, the stem no longer grows, but the cephalium will continue growing, sometimes to 1 m tall. The small flowers emerge on top of the cephalium, often in rings. The fruits are pink or red, resembling small candles.

The generic name is a shortened form of the original name Echinomelocactus, derived from the Greek ekhinos (‘hedgehog’), melon (‘apple’), and kaktos (see top of this page), thus ‘spiny apple plant’, presumably referring to the shape and appearance of young plants of this genus. The popular name Turk’s cap was given in allusion to the cephalium.

Melocactus intortus

This plant is restricted to islands in the eastern half of the Caribbean. It is one of the larger species of the genus, growing to 1 m tall, not including the cephalium.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘twisted’. When Scottish horticulturalist and botanist Philip Miller (1691-1771) described this plant in 1768, he noted that the ribs were “spirally twisted”. Well, they may have been twisted on his specimen, but usually they are not.

Melocactus intortus, Bosque del Guanica, Puerto Rico. The bottom picture shows an aberrant form with several cephalia. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Miqueliopuntia miquelii

The sole member of the genus, growing in coastal regions of northern Chile. This plant, which forms dense thickets, has cylindrical, jointed stem segments with prominent tubercles, on which the areoles and many glochids occur. The cup-shaped flowers are pink, white, or yellowish green.

The generic and specific names were given in honour of Dutch botanist Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel (1811-1871), director of the herbarium at University of Utrecht.

Flower and fruits of Miqueliopuntia miquelii, south of Vallenar, Chile. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia Prickly pear cactus

Members of this genus, and of the genus Consolea (above), are characterized by their broad, flat stem segments, called cladodes.

Opuntia, comprising between 150 and 180 species, occurs from southern Canada southwards to southern South America. It is named for the Ancient Greek city of Opus, where, according to scholar and botanist Theophrastos (c. 371-287 B.C.), an edible plant grew, which could be propagated by rooting its leaves – just like prickly pears can be propagated by rooting their stem segments. (Source: U. Quattrocchi 2000. CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names)

Opuntia basilaris Beavertail prickly pear

This cactus is distributed from the Californian Anza-Borrego, Mohave, and Colorado Deserts eastwards across southern Nevada and Utah southwards into north-western Mexico. Most plants are without spines, but have numerous glochids in the areoles.

The specific name is drived from the Latin basis (‘pedestal’, ‘foot’, ‘base’) and aris, a suffix, thus ‘footed’, or ‘on a pedestal’. What it refers to is not obvious.

The common name alludes to the pads, which are more or less wrinkled, resembling a beaver’s tail.

Beavertail prickly pear, Joshua Tree National Park, California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia engelmannii Engelmann’s prickly pear

The range of this plant is from California eastwards to Louisiana, and thence southwards to Sonora and Chihuahua states, Mexico. In the Sonoran Desert, its terminal pads mostly face east-west, to maximize the absorption of solar radiation during summer rains.

The specific and common names commemorate German-American botanist George Engelmann (1809-1884), who described many plant species, especially in the Rocky Mountains and northern Mexico.

This species has been introduced elsewhere, and in Kenya it is regarded as an invasive.

Engelmann’s prickly pear, Mazatzal Mountains, Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spines and glochids in areoles of Engelmann’s prickly pear, Mazatzal Mountains. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia humifusa Eastern prickly pear

This hardy plant grows in open, sunny areas, from south-eastern Canada southwards in a belt along the eastern coast of the United States into northern Mexico.

The specific name is derived from the Latin humus (‘ground’) and fusus, from fundere (‘to spread’), in a botanical context meaning ‘procumbent’.

Some botanists do not recognize this species, but treat it as a variety of O. compressa.

Young pads of eastern prickly pear, Assateague Island, Maryland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia littoralis Coastal prickly pear, western prickly pear

As its name implies, this plant is found in coastal regions, growing in sage scrub and chaparral, from the Los Angeles area in southern California southwards to southern Baja California.

The specific name is derived from the Latin litorale (‘of the seashore’).

Coastal prickly pear with fruits, Ronald W. Caspers Wilderness Park, Santa Ana Mountains (top), and Point Mugu State Park, both in California. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Spines and glochids in areoles of coastal prickly pear, Torrey Pines State Park, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia phaeacantha Tulip prickly pear

This species is distributed from California eastwards to Colorado and Texas, and thence southwards into northern Mexico. Its flowers may be red, orange, or yellow, or often yellow with reddish centre.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek phaios (‘dusky’, ‘grey’, ‘brown’) and akanthos (‘spiny’), alluding to the spines, which are often dark.

Tulip prickly pear, Saguaro East National Park (top) and Pima Canyon, both in Arizona. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia pinkavae Pinkava’s prickly pear

This prostrate species, to 25 cm tall, is also known as Bulrush Canyon prickly pear. It is restricted to a small area in northern Arizona and southern Utah, growing in grasslands and pinyon-juniper woodlands. It may have many or few pale spines, to 7 cm long, and the flowers are magenta or purple.

The specific and common names commemorate Dr. Donald Pinkava (1933-2017), who studied the genus Opuntia for many years.

Pinkava’s prickly pear, Lake Powell, Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia spinosibacca

This plant is restricted to a small area in and around the Big Bend region of western Texas and adjacent Coahuila in Mexico. It grows to 1.5 m tall, segments flat, green, often purple near the areoles, to 25 cm long and 11 cm broad, flowers yellow or yellow-orange with a bright red centre.

The specific name is derived from the Latin spinosus (‘full of spines’) and bacca (‘berry’), alluding to the very spiny fruits.

Opuntia spinosibacca, Big Bend National Park, Texas. In the upper picture, Chisos lupine (Lupinus hartmannii) is seen in the background. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pilosocereus

This genus, comprising about 37 species, is widespread from Mexico and the Caribbean southwards throughout South America. The generic name is from the Latin pilos (‘hair’), referring to the very hairy areoles of this genus, and cereus, derived from the Greek keros (‘wax candle’). Originally, Cereus was the name of a large number of cacti, referring to the slender and columnar shape of many of these plants.

Pilosocereus royenii

This blue-stemmed, tree-like cactus, which may be up to 8 m tall, is one of the commonest cacti in the Caribbean, and is also found on the Yucatan Peninsula, eastern Mexico. It grows in dry, rocky scrubland, on cliffs, beaches, and plains.

Pilosocereus royenii has blue stems, which may be up to 8 m tall, here photographed in Bosque del Guanica, Puerto Rico. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture, Pilosocereus royenii (left) grows in dry scrub forest together with another cactus, Melocactus intortus (above), Bosque del Guanica, Puerto Rico. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stenocereus

This genus, comprising 23 species of mostly shrubby or tree-like columnar cacti, is found in southern United States, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and northern South America.

The generic name is derived from the Greek stenos (‘narrow’), referring to the narrow ribs on most species, and the Latin cereus, derived from the Greek keros (‘wax candle’). Originally, Cereus was the name of a large number of cacti, referring to the slender and columnar shape of many of these plants.

Stenocereus aragonii

This species is restricted to a rather dry area along the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica.

Presumably, the specific name alludes to the region Aragón in northern Spain, which got its name from the Aragón River, originating in the Pyrenees.

Dry tropical forest on a rocky hill in Santa Rosa National Park, Guanacaste, Costa Rica, with vegetation of Stenocereus aragonii (right), gumbo-limbo (Bursera simaruba, with brown trunks), and piñuela (Bromelia pinguin), a pineapple-like bromeliad. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Stenocereus thurberi Organ-pipe cactus

This huge cactus, growing to 5 m tall, resembles saguaro (above), but is branched from ground-level. It is mainly found in northern Mexico, in the Sonora Desert and on Baja California, with a small population in the extreme southern United States, notably in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona.

The specific name honours American botanist George Thurber (1821-1890). The name organ-pipe cactus refers to the stems, which resemble pipes of a church organ. In Spanish, fruits of this species are known as pitaya dulce (‘sweet pitaya’), the word pitaya referring to edible fruits of Mexican cacti in general.

Organ pipe cactus, photographed in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, southern Arizona. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Close-up view of organ pipe cactus, showing areoles with spines, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Usage of cacti

Numerous species of cacti are cultivated for their wonderful flowers. The fruits of many species are edible and sweet-tasting, but they must be peeled carefully to remove the glochids. Some indigenous peoples, including the Tequesta, would roll the fruit in sand to get rid of the glochids. They are also easily removed by using fire. The most common culinary species is Indian prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica), which is widely cultivated around the world.

During periods of drought, collared peccaries (Pecari tajacu), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), and other wild animals often feed on cacti to quench their thirst. The flesh is also an excellent feed for domestic animals.

In Mexican traditional medicine, prickly pear pulp and juice are utilized for wounds and inflammation of the digestive and urinary tracts.

Juice, extracted from pads and stems, especially of Indian prickly pear, is utilized as an additive in earthen plaster.

Cactus flesh can be used for water purification.

For thousands of years, peyote (Lophophora williamsii) has been utilized by native peoples in northern Mexico and south-western United States for production of mescaline, which was used as a hallucinogen in religious rites.

Peeled fruits of Indian prickly pear for sale, Damascus, Syria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chomp! – Partly eaten pad of a prickly pear, Mohave National Preserve, California. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Various prickly pear cacti are used as very effective hedges around the world, here near Sfax, Tunisia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This church door in the village of Toconao, San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, is constructed of cactus wood. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Opuntia in dye production

Dactylopius coccus is a scale insect of the family Dactylopiidae, which is native to tropical and subtropical Latin America. This insect is partial to prickly pears, feeding on the sap. It produces a carminic acid, which is extracted from its body and eggs to make a red dye, called cochineal dye, primarily used as food colouring and for cosmetics.

Cochineal was utilized by the Aztec and Maya peoples as far back as c. 700 B.C. for dyeing clothes and as paint. Later, the dye was almost exclusively produced in Oaxaca, Mexico, and it became the country’s second-most valued export after silver. When artificial food dyes emerged, cochineal production declined, but recent increased demand for healthy foods has renewed its popularity. Today, the main producers of the dye are Peru, Chile, and the Canary Islands.

Mexican coat of arms

The Mexican coat of arms depicts a golden eagle with a rattlesnake in its beak, perched on a prickly pear cactus. According to the official history of Mexico, this coat of arms is inspired by an Aztec legend regarding the founding of their capital, Tenochtitlan.

The Aztecs, who were nomads in those days, were searching for a place to build this capital. Huitzilopochtli, deity of the sun, and of war and human sacrifice, commanded them to find an eagle devouring a snake, perched atop a cactus, which grew on a rock in a lake. After 200 years of wandering, they spotted the promised sign on a small island in a swampy lake, Texcoco. Here, they founded their new capital, which they named Tenochtitlan after a local species of prickly pear, in Nahuatl tenochtli. (Source: J.B. Minahan 2009. The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems)

By mistake, this species was named Cactus ficus-indica (‘Indian fig cactus’) by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), presumably because he thought that it originated in India. It was later renamed Opuntia ficus-indica, in daily speech called Indian prickly pear.

The Mexican coat of arms depicts a golden eagle with a rattlesnake in its beak, perched on a prickly pear cactus. (Illustration: Public domain)

Main sources

cactiguide.com/cactus

iucnredlist.org

llifle.com/Encyclopedia/CACTI/Family/Cactaceae

Anderson, E.F. 2001. The Cactus Family. Timber Press, Portland

Tweit, S.J. 1992. The Great Southwest Nature Factbook – a Guide to the Region’s Remarkable Animals, Plants and Natural Features. Alaska Northwest Books, Seattle

(Uploaded March 2019)

(Latest update November 2022)