Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Plants of Sierra Nevada

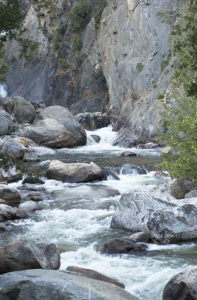

The Sierras harbour three national parks: Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon, besides 20 wilderness areas and two national monuments. Prominent features in these mountains include Mount Whitney (4421 m), the highest peak in the lower 48 states, Lake Tahoe, the largest alpine lake in North America, and Yosemite Valley, which is certainly one of the most spectacular valleys on the continent, sculpted by glaciers from ancient granite rocks.

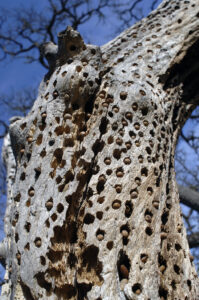

An Ahwahneechee legend relates that, long ago, two travellers, Tissiak and her husband Tokoyee, were quarrelling with each other. He became so enraged that he began beating her, which made her so angry that she hurled her basket of acorns at him. As they stood facing each other, they were turned to stone for their wickedness. The acorn basket (Basket Dome) lies upturned beside Tokoyee (North Dome), and the rock face of Tissiak (Half Dome) is stained with her tears.

1) Foothill grasslands, oak woodlands, and chaparral (including Great Basin dry zone on eastern slopes), altitude c. 300-900 m. Indicator species: grey pine (Pinus sabiniana) and blue oak (Quercus douglasii). Chaparral is a community of shrubby plants, adapted to dry summers and moist winters, which is typical of southern California.

2) Lower montane forest (dry south-western part), altitude c. 900-2100 m. Indicator species: ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and Jeffrey’s pine (P. jeffreyi).

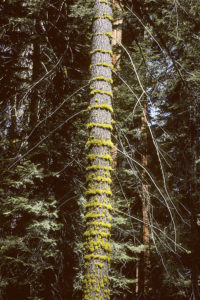

3) Lower montane forest (moist north-eastern part), altitude c. 900-2100 m. Indicator species: ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum).

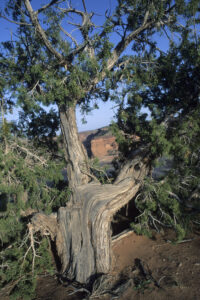

4) Piñon pine – juniper woodland (eastern dry slopes), altitude c. 1500-2100 m. Indicator species: singleleaf piñon (Pinus monophylla) and Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma).

5) Upper montane forest, altitude c. 2100-2700 m. Indicator species: red fir (Abies magnifica) and tamarack pine, or Sierra lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta ssp. murrayana).

6) Subalpine zone, altitude c. 2700-2900 m. Indicator species: whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis).

7) Alpine zone, above c. 2900 m. Indicator species: willow shrubs (Salix spp.).

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the sessile oak (Quercus petraea), possibly derived from aigilops, the classical Greek name of an oak with edible acorns. As horsechestnut fruits are poisonous, it is indeed a bit of a mystery, why Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) named the genus Aesculus. However, it must be pointed out that the meal is edible after boiling the fruits, and it was formerly used as cattle and chicken feed.

The name horsechestnut comes in part from at kestanesi, the Turkish name of the European A. hippocastanum, and the horse-part stems from the usage of the fruits to treat ailments in horses, including excessive wind. The name buckeye stems from an American indigenous tribe, who called the nut hetuck, which means buck-eye, alluding to the markings on the nut, which resembles the eye of a deer.

Its large nuts are poisonous. Several indigenous peoples, including Pomo, Yokut, and Luiseño, used to catch fish by strewing pounded nuts into streams, causing the stupefied fish to float on the surface.

Other members of this genus are presented elsewhere, European horsechestnut on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees, and Indian horsechestnut (A. indica) on the page Plants: Himalayan flora 3.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for pines, maybe originally stemming from Sanskrit pitu (‘sap’ or ‘resin’), alluding to the ample production of resin in this genus.

The specific name honours English lawyer, naturalist, and horticulturist Joseph Sabine (1770-1837) who had a lifelong interest in natural history, a fellow of the Linnean Society and honorary secretary of the Royal Horticultural Society.

The name grey pine alludes to the grey foliage, whereas digger pine may stem from early settlers, who observed Paiute people digging around these trees for their seeds.

Male flowers are in pendent catkins, females mostly in erect spikes. The fruit is a nut, called an acorn, which is partly enclosed in a cupule (see family above), consisting of overlapping bracts, mostly with free tips.

The generic name is the classical Latin term for oaks. It probably stems from the name of the Lithuanian god of thunder, Perkunas. The word oak is from the Anglo-Saxon ek, in ancient Germanic aik, of uncertain origin and meaning.

The specific name was given in honour of Scottish gardener and botanist David Douglas (1799-1834), who explored the North American flora during three expeditions. He introduced Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and other conifers, especially pine species, as well as a number of bushes and herbs, into British cultivation. In a letter to Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), director of the Botanical Gardens of Glasgow University, he wrote, “You will begin to think I manufacture pines at my pleasure.”

Douglas died under mysterious circumstances while climbing Mauna Kea in Hawaii in 1834. Apparently, he fell into a pit trap and was possibly crushed by a bull that fell into the same trap. He was last seen at the hut of Englishman Edward ‘Ned’ Gurney, a bullock hunter and escaped convict. Gurney was suspected in Douglas’s death, as Douglas was said to have been carrying more money than Gurney subsequently delivered with the body. (Source: Nisbet, J. 2009. The Collector: David Douglas and the Natural History of the Northwest. Sasquatch Books)

It was named in honour of Nicholas Garry (1782-1856), who was deputy governor of the Hudson Bay Company 1822-35.

The specific name was given in honour of Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus (1810-1889), a German-born physician, explorer, and botanist, who first collected it.

The generic name was given as a tribute to German businessman and politician Wilhelm Amsinck (1752-1831), who was a benefactor of the Hamburg Botanical Garden.

It was named in honour of Canadian botanist Alice Eastwood (1859-1953), who created the botanical collection at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

The generic name is composed of Ancient Greek hesperos (‘western’), and the genus name Yucca.

Its narrow leaves are all basal, to 1 m long, grey-green, stiff, saw-toothed, ending in a sharp point. It only has one inflorescence, a large panicle with hundreds of bell-shaped, white or purplish flowers, situated at the end of a thick stalk, which grows very fast, reaching a height of up to 3 m.

Other common names of this spectacular plant include Our Lord’s candle, in allusion to the huge inflorescence, and Spanish bayonet, which, of course, refers to the needle-sharp tips of the leaves.

The specific name honours Amiel Whipple (1818-1863), head surveyor during construction of the Pacific Railroad.

According to Collins English Dictionary, the generic name, and with that the common name, stems from the Latin lupinus (‘wolfish’), referring to an old belief that these plants would ravenously exhaust the soil.

The specific name was given in honour of army physician Charles Austin Stivers, who first collected it in 1862, near Yosemite. The harlequin part refers to the vivid flower colours of this plant, likened to an Italian Middle Age comic figure, Arlecchino (in English Harlequin), who is characterized by his chequered costume.

Some authorities consider it synonymous with the widespread chick lupine (L. microcarpus).

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek tri (‘three’) and teleos (‘perfect’), referring to the flower parts, which are in multiples of 3, for instance the 6 petals.

Previously, these plants were included in the family Themidaceae, but were since moved to Brodiaeoideae, a subfamily of the asparagus family (Asparagaceae).

At least 5 subspecies are known, of which scabra, called foothill prettyface, is mainly restricted to the foothills of the Cascades and the Sierras, growing in open sandy places up to elevations around 2200 m.

The specific name means ‘Ixia-like’, alluding to its (slight) resemblance to Ixia, a genus in the iris family (Iridaceae).

The flowers are small and white, and the fruit is a one-seeded nut (an achene), with the long, plumelike style still attached. The generic name refers to this plume, derived from Ancient Greek kerkos (‘tail’) and karpos (‘fruit’), thus ‘tailed fruit’. The name mahogany alludes to the hard, dark wood of these trees, but they are entirely unrelated to true mahogany, of the family Meliaceae.

The leaves are quite distinctive, entire in the lower half, then toothed to the rounded tip. They somewhat resemble birch leaves (Betula), which gave rise to its specific and popular names.

The generic name builds on a misunderstanding. It is a variant of yuca, which is supposedly derived from kari’na yuca, a Caribbean name of cassava (Manihot esculenta). The word was applied to these plants in 1753 by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who may have confused them with the cassava plant.

Its popular name stems from Californian Mormons, who encountered this plant on their way to settle with their fellow soul mates in Utah. To them, the outstretched ‘arms’ of this tree recalled the Biblical Joshua, guiding the Children of Israel to the Land of Canaan.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek khrysos (‘gold’) and thamnos (‘bush’), referring to the golden-yellow flowers of these plants.

Previously, it was utilized medicinally by a variety of indigenous peoples, among the Paiute to treat colds and cough, and among the Hopi for skin problems. Gosiute and Paiute produced chewing gum from latex of the roots, whereas Hopi and Navajo made orange and yellow dyes from the flowers.

The specific name is derived from the Latin viscum (a birdlime, made from the mistletoe), and flos (‘flower’), thus ‘sticky-flowered’.

The generic name is derived from the Hindi name of these plants, dhatura. The common name alludes to the extremely spiny fruit.

It is native from the south-western United States southwards to Guatemala, and has also been widely introduced as an ornamental, or inadvertently, to all continents except Antarctica.

It contains the highly toxic alkaloids atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine. The Aztecs used this plant long before the Spanish conquest for many therapeutic purposes, including as a poultice for wounds. The Aztecs warned against ingestion of it, as it might cause madness. Nevertheless, various indigenous tribes used it as a hallucinogenic.

The effects of scopolamine and hyoscyamine are described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry, under Hyoscyamus niger. On the same page, you may read an amusing anecdote from 1676, describing the altered mental state of British soldiers, who consumed common thorn-apple (D. stramonium).

When Scottish botanist Philip Miller (1691-1771) first described this plant in 1768, he misspelled the Latin word innoxia (‘inoffensive’), when naming it Datura inoxia. Another name, D. meteloides, has also erroneously been applied to it.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek di (‘double’) and plakos (‘a flat, round plate’). In his publication from 1838, On Two New Genera of California Plants, English naturalist Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859) says: “The generic name alludes to the splitting of the capsule, attached to each valve of which is seen a large placenta, and under its edges are found the slender, subulate seeds.”

These plants were previously included in the genus Mimulus.

It is one among many species, which were named in honour of surgeon and botanist John Milton Bigelow (1804-1878), who collected many new plant species on expeditions to south-western U.S. and northern Mexico.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek erion (‘wool’) and gony (‘knee’), alluding to the hairy nodes of the first species to be described, E. tomentosum.

The stems, to about 1.5 m tall, are spreading or erect, stem leaves singly or in bundles at each node, blade linear or oblanceolate, to 1.5 cm long and 5 mm wide, white-woolly or sometimes almost smooth above, greyish or green below, margin often inrolled. The inflorescence is widely branched, rounded or occasionally flat-topped, with numerous compact heads, to 2 cm across, flowers white or pinkish, to 3 mm across.

In former days, this species was widely used medicinally by various tribes for numerous ailments, including colds, headache, diarrhoea, and wounds. It was also eaten raw or used in porridges and baked items, and tea was made from leaves, stems, and root. Today, it is a very important source of honey.

The specific name is a diminutive of the Latin fascis (‘bundle’), referring to the leaf clusters.

The generic name is composed of Ancient Greek kalos (‘beautiful’), and the genus name Cedrus (‘cedar’). However, these trees are not closely related to true cedars, which belong to the pine family (Pinaceae).

The common name alludes to the leaves, which emit a fragrance when crushed.

Indigenous peoples utilized it for numerous purposes, the bark to construct temporary conical-shaped huts and also more permanent houses, and to produce fire by friction. Hunting bows and baskets were made from thin branches. It was also used medicinally for stomach problems.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘extending down’, referring to the leaves extending down the twig.

It is native from Oregon south through California to Baja California.

Scottish botanist David Douglas (1799-1834) named it lambertiana in honour of English botanist Aylmer Bourke Lambert (1761-1842). The common name stems from its sweet resin, which indigenous tribes used as a sweetener. The famous Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) preferred it to maple sugar.

The sad fate of David Douglas is related above (see Quercus douglasii).

Ponderosa pine is native to a huge area in western United States and Canada, found from British Columbia southwards to southern California, eastwards to South Dakota and New Mexico.

It was first collected in 1826 by David Douglas (see Quercus douglasii above), who labelled it Pinus ponderosa, from the Latin ponderosus (‘heavy’), referring to its heavy wood.

This species is adapted to fire, protected from smaller fires by its thick bark. It is killed by larger fires, but easily sprouts again from the roots. Acorns mainly sprout, when a fire has cleared an area of leaf litter. This was known by several indigenous peoples, who purposely lit fires to renew growths of this tree, whose acorns was a staple food source to them.

The specific name honours American physician and botanist Albert Kellogg (1813-1887), one of the founding members of the California Academy of Sciences.

Members of this genus have no ray florets, but very conspicuous, floret-like involucral bracts.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek ana, which has several meanings, in this connection probably ‘exceedingly’, and phalos (‘white’), referring to the white, pearl-like flowerheads.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek margarites (‘pearl’), likewise alluding to the white, pearl-like flowerheads.

The genus was named to commemorate botanist John Clayton (c. 1694-1773), who served as an Anglican minister in the Colony of Virginia.

It occurs from southern Alaska southwards through western United States and Mexico to Central America. It is common in the Sierras.

In Europe, where it was cultivated as a vegetable as far back as in the 1500s, it is widely naturalized today.

The specific name refers to plants, in which the leaves are clasping the stem. The name miner’s lettuce stems from the 1849 Gold Rush in California, when miners ate this plant as a fresh salad, presumably to avoid getting scurvy.

The generic name was used as early as 1561 for E. angustifolium (today called Chamaenerion angustifolium) by Swiss physician and naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) in his unfinished work Historia plantarum. He composed the name from Ancient Greek ion epi lobion (‘violet on a pod’), lobion literally meaning ‘fruit of the cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), alluding to the similarity of the flower colour to that of certain violets (Viola), and to its pod-like fruit.

The common name refers to the similarity of the leaves of some species to those of certain species of willow (Salix).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘grey’ or ‘ash-coloured’, presumably referring to the leaves, which may sometimes be greyish, but are usually green.

Previously, it was called Zauschneria californica, named in honour of physician and botanist Johann Zauschner (1737-1799) of Prague. However, genetic research has revealed that it is in fact a species of willow-herb.

The popular name refers to the scarlet flowers, which resemble those of fuchsias. Hummingbirds are much attracted to these flowers, giving rise to two other common names, hummingbird flower and hummingbird trumpet.

The generic name is a Latinized version of erysimon, the classical Greek name of a species of hedge-mustard, Sisymbrium polyceratium. Some authorities suggest that it stems from erymai (‘to protect’ or ‘to save’), presumably alluding to the usage of Sisymbrium species to cure inflammation of the throat. Why the name was applied to these plants is not clear.

Formerly, it was used medicinally by indigenous peoples for various ailments, including stomach ache and muscle pain.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘forming a head’, referring to the dense inflorescence.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of the silver fir (A. alba), probably derived from the Ancient Greek name of the plant, abin. The English name is probably derived from Old Norse fyri, which, however, was the word for pine trees (Pinus).

White fir may live up to 300 years. The largest specimens have been found in the central Sierras, of which the largest was 75 m tall, with a trunk diameter of 4.6 m at breast height.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘of the same colour’, alluding to the needles, which have the same colour above and below.

These plants, comprising about 130 species of deciduous trees or large shrubs, are widespread in the Northern Hemisphere, with most species in Asia, others in Europe, northern Africa, and North and Central America. Only a single species occurs in the Southern Hemisphere.

The leaves are palmate in most species, and the foliage often turns a brilliant red or yellow in autumn. A number of pictures, depicting this autumn foliage, are found on the page Autumn.

The fruit consists of 2 connected single-seeded units, each with a long wing. When ripe, the fruits are often propelled a considerable distance by the wind. An account of the effectiveness of this spreading is described on the page Nature reserve Vorsø: Expanding wilderness.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for maples.

Pictures, depicting the yellow autumn foliage of this species, may be seen on the page Autumn.

The generic name is the classical Latin name of alders. Some authorities connect the name with High German elo (’greyish-yellow’), and with Sanskrit aruna (’reddish-yellow’), referring to the fact that the wood of common alder (A. glutinosa), when cut, assumes a bright reddish-brown colour. The common name evolved from the Old English word for these trees, alor, which in turn derived from Proto-Germanic aliso.

The specific name refers to the leaves, whose shape is sometimes rhombic.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘horn’. It was the classical name of Cornelian dogwood (C. mas), whose wood is so dense that it will sink in water. The prefix dog may imply that the fruits of common dogwood (C. sanguinea) are of little value, due to their bitter taste. Alternatively, it may refer to the former usage of dogwood shoots, which were sharpened and used by farmers as cattle prods, called dags. Skewers were also made from the tough and durable wood.

It is native along the Pacific Ocean, from southern British Columbia to southern California. Inland populations are found in the Sierras, and also in central Idaho. In 1956, this tree was appointed as the provincial flower of British Columbia.

In his book My First Summer in the Sierra, from 1911, Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) writes about this tree: “Nuttall’s flowering dogwood makes a fine show when in bloom. The whole tree is then snowy white. The involucres are six to eight inches [15-20 cm] wide. Along the streams it is a good-sized tree thirty feet [9 m] high, with abroad head when not crowded by companions. Its showy involucres attract a crowd of moths, butterflies, and other winged people about it for their own, and, I suppose, the tree’s advantage.”

The specific name was given in honour of Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), a British printer, who came to the United States in 1808. Shortly after his arrival, he met botanist Benjamin Barton (1766-1815), who induced a strong interest in natural history in him. During the following years, until 1841, Nuttall undertook several expeditions in America, and numerous plants and animals are named after him.

The leathery leaves are entire or toothed, glossy green above. Young leaves are covered in yellowish down beneath, often turning grey and almost hairless the second year. The acorns vary quite a lot, but are mostly ovoid, with a shallow, turban-like, scaly cup, densely covered in yellowish hairs, which gave rise to the specific name, derived from Ancient Greek khrysos (‘gold’) and lepis (‘scale’).

After leaching of the tannins, the acorns were a staple food of many indigenous tribes. They have also been used as a coffee substitute.

The following quote of Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914), from 1870, is cited in the book John Muir: His Life and Letters and Other Writings, edited by T. Gifford, Mountaineers Books, 1996: “Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia! Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia and have been and am at his feet, fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods, in the world? Where are such columns of sunshine, tangible, accessible, terrestrialized?”

Most people of that period did not share Muir’s enthusiasm. Despite the fact that their wood is fibrous and brittle, and of little use for construction, thousands of these magnificent trees were ruthlessly cut down, between the 1880s and 1924, even though their commercial value was marginal. The heavy trees would often shatter when they hit the ground, and it has been estimated that as little as 50% of the timber came to use. The wood was utilized mainly for shingles and fence posts, or even for matchsticks. – Imagine! From grand tree to matchstick!

Today, fortunately, felling of this species is strictly forbidden, and a few magnificent groves have been saved.

The generic name is composed of the genus name Sequoia (Californian redwood), and Ancient Greek dendron (‘tree’).

Other pictures, depicting these impressive trees, may be seen on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.

It grows to 30 m tall, with fragrant lance-shaped leaves, to 10 cm long. The yellow or yellowish-green flowers are arranged in small umbels, which has given rise to the generic name, meaning ‘little umbel’. The fruit is an oval berry, to 2.5 cm long, green at first, purple when mature.

The leaves have been used as a substitute for those of the true bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) in cooking. They were utilized by native tribes for a number of ailments, including headache, toothache, earache, stomach ache, colds, sore throat, and mucus in the lungs. A poultice of the leaves was used for rheumatism and neuralgia.

Many American species are characterized by having smooth, orange or reddish bark, and stiff, twisting branches. Several species occur in the Sierras, many of them quite similar and often difficult to identify.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek arktos (‘bear’) and staphyle (‘a bunch of grapes’), alluding to the fruits, which form grape-like clusters in many species. They are much relished by bears.

The word manzanita is Spanish, a diminutive of manzana (‘apple’), referring to the fruits.

Red bearberry (A. uva-ursi), and a presumed hybrid between this species and hairy manzanita (A. columbiana), often called A. x media, are presented on the page Autumn.

In the past, the Miwok people of northern California made cider from the fruits.

The specific name is derived from the Latin viscidus (‘sticky’), alluding to the glandular leaves and fruits.

In the past, this genus and the genus Viburnum constituted the family Sambucaceae, but were then transferred to the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae), and later to the moschatel family (Adoxaceae), which is today called Viburnaceae.

The generic name is derived from Ancient Greek sambuca, the name of an ancient instrument of Asian origin. Presumably, flutes were made from the branches. The name elder is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word aeld (’fire’). In those days, the hollow stems of elder were used to kindle a fire.

It grows in a variety of habitats, including river valleys, woodlands, and exposed slopes with access to water, up to altitudes around 3,000 m. It has a very wide distribution, from British Columbia southwards through much of western United States to north-western Mexico, with scattered occurrence in Oklahoma and Texas.

Many indigenous tribes used the berries of this plant for food, and a number of herbal medicines were produced from its wood, bark, leaves, flowers, and roots. The wood was also used to make pipes and musical instruments, such as flutes and small whistles. A dye was obtained from the berries.

These plants of the broomrape family (Orobanchaceae) are parasitic, obtaining a large part of their nutrients from roots of other plants.

The flowers of some species are edible and were formerly consumed by various native tribes, but as these plants tend to absorb and concentrate selenium in their tissue, roots and green parts can be very toxic.

An attractive plant, distributed from south-western Oregon through much of California, just extending into Baja California.

Formerly, members of the Miwok and Pomo tribes used it medicinally for treatment of wounds, burns, diarrhoea, and eye trouble.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘orange-coloured’.

These plants have a hollow, jointed, silica-containing stem with 3-40 longitudinal grooves. The leaves, often reduced to scales, are arranged in whorls at each joint. There are two distinct types, of which one has brown, fertile spring shoots and green, sterile summer shoots, which supply the photosynthesis. The other group has only green summer shoots, with terminal sporangies. They vary from dwarf plants, 20 cm tall, to giants up to 8 m tall.

The generic name is derived from the Latin equus (‘horse’), and seta, which has several meanings, including ‘rough’, ‘brush’, or ‘hair’. The latter word can refer to the rough, silica-containing stems of these plants, but together with equus, the word means ’horse hair’. With a bit of imagination, a bunch of drying stems do resemble a horsetail.

A number of horsetail species are described on the page Plants: Plants in folklore and poetry.

It grows in wet areas in forests, often on slopes along streams. In Japan, it is cultivated in ponds in ornamental gardens.

Certain indigenous American tribes used a decoction of the stems for venereal diseases and as a diuretic.

The specific name is derived from the Latin hiems (‘winter’), and the suffix alis, thus ‘found in winter’, referring to the evergreen stems.

The name scouring rush stems from its former usage as a scouring remedy, and as sandpaper, due to its high content of silica.

The generic name honours Swedish-born American naturalist Thure Ludwig Theodor Kumlien (1819-1888), who contributed much to the knowledge of the natural history of Wisconsin. He taught botany and zoology, as well as foreign languages, at the Albion Academy.

Some authorities, including Kew Gardens of London, do not accept this genus, but include it in Ranunculus.

The specific name is derived from hystrix, the classical Greek word for porcupine. The connection to this plant is hard to see.

Native peoples of California utilized these plants for a variety of purposes. Arrow poison was produced from their toxic foliage. Klamath people would soak porcupine quills in an extract of the plants, which dyed them yellow. They were then woven into baskets to make patterns. The Okanagan-Colville tribe used these lichens medicinally, internally for stomach problems, externally for wounds.

The generic name is Latin, meaning ‘deadly’, alluding to the toxicity of these plants. In the old days, Norwegians used common wolf lichen to kill wolves and foxes. The toxic foliage was mixed with crushed glass, and then stuffed into a carcass on frozen ground. The specific name vulpina refers to foxes, in Latin Vulpes.

The generic name is derived from madi, a native Chilean name of the coast madia (M. sativa). Their foliage exudes a fragrant oil, hence the common name tarweed.

The small nut-like fruits (achenes) were previously eaten raw by several indigenous tribes, or ground into flour and baked.

The leaves of these plants are arranged in a basal rosette, and the flowers are usually in terminal umbels on a leafless stalk. The petals are usually fused, forming a tube with 5 terminal, spreading lobes.

A large number are very hardy, reflected in the generic name, which is a diminutive of the Latin prima (’first’), referring to the early flowering of several species. The name primrose stems from the Latin prima rosa, meaning ‘the first rose’, although primroses are not even distantly related to roses.

According to some authorities, the name cowslip is a corruption of an Old English word, cuslyppe (‘cow dung’). This probably refers to the favoured habitat of the common cowslip (P. veris), namely dry slopes, grazed by cattle. Others claim that the word is a corruption of cow’s leek, derived from the Anglo-Saxon word leac (‘plant’).

It has been said that the name oxlip, which is a corruption of ox and slip, refers to the fact that oxlip, like cowslip, often grows on cattle grazing grounds. This may be a wrong presumption, as true oxlip (below) – at least in the northern part of its distribution area – mainly grows in forests.

The role of these plants in folklore and traditional medicine is described on the page Plants: Primroses. Shooting stars are a group of primroses, which were formerly placed in the genus Dodecatheon, derived from Ancient Greek dodeka (’twelve’) and theos (’god’), thus ‘twelve gods’. The Greeks applied this name to plants that they thought had acquired their medicinal properties from the twelve most prominent gods and goddesses. The genus was erected by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), supposedly in allusion to the inflorescence of these plants often consisting of 12 flowers.

This group, comprising 17 species, is widespread in North America, from north-western Mexico northwards through western United States and Canada to Alaska, with a single species extending into north-eastern Siberia. The flowers are pollinated by bees, which cling to the petals by beating their wings very fast, thus releasing the pollen.

The popular name shooting star refers to the flowers, in which the yellow stamens and the petals, which are bent backwards, converge to a common point, likened to a shooting star, in which the petals constitute the ‘tail’.

The Nlaka’pamux people used the flowers as amulets and love charms.

It was named in honour of Scottish botanist John Jeffrey (1826-1854), who spent four years exploring and collecting plants in Washington, Oregon, and California, sending his specimens back to Scotland. In 1854, he disappeared while travelling from San Diego across the Colorado Desert, and was never seen again.

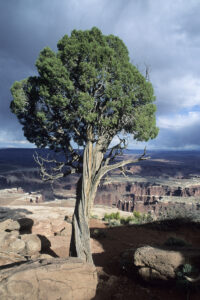

There are various theories as to the origin of the generic name. Some authorities claim that it stems from the Latin iungere (’tie together’ or ’weave’), referring to the use of its branches in baskets and fences, whereas others maintain that it is derived from juvenis (’young’) and parere (’to produce’), referring to the fact that juniper bushes constantly are renewed by new shoots.

The words gin and genever are derived from Juniperus, attesting to the usage of juniper fruits in these beverages.

The cones are berry-like, to 1.3 cm across, bluish-brown, with a whitish waxy bloom.

In former days, Native Americans used the bark for a variety of purposes, including beds, and ate the cones both fresh and in cakes. The gum was smeared on wounds as a protective covering. Tea made from the leaves was given to women to calm their contractions after giving birth. The Navajo would sweep their tracks with boughs from the tree, so that death would not follow them.

The specific name is derived from Ancient Greek osteon (‘bone’) and sperma (‘seed’), alluding to the hard seeds of this species.

It is one among several pines of the piñon pine group, which are native to western United States and north-western Mexico, from southernmost Idaho, Utah, and south-western New Mexico westwards to eastern and southern California and Baja California.

This tree, which grows to 20 m tall, usually occurs at altitudes between 1,200 and 2,300 m. It is very common, forming open woodlands, often mixed with junipers.

As described in the quote above, the edible nuts were formerly an important source of food for indigenous peoples, and they are still widely harvested.

Tamarack pine is widely distributed in mountains, from Washington southwards to northern Baja California, and thence eastwards to southern Nevada. The nominate contorta is found along the Pacific Coast from southern Alaska to north-western California. Another coastal subspecies is bolanderi, which is endemic to Mendocino County, north-western California. It is threatened by urban development. Finally, ssp. latifolia is found in the Rocky Mountains, from Yukon and Saskatchewan southwards to Colorado.

The specific name is derived from the Latin con (‘with’) and torqueo (‘twisted’), referring to the low, twisted trees, commonly found along the Pacific Coast. This is also reflected in one of the common names of this species, twisted pine.

Native peoples often used this species to build their lodges, hence the common name lodgepole pine.

The leaves are broad, mostly heart-shaped, with a long, slender stalk, which is flattened, making the leaf rustle in the wind. Inflorescences are pendent catkins, with numerous tiny flowers clustered around a central axis, each flower surrounded by papery bracts. The flowers are wind-pollinated, seeds fluffy, spread by the wind.

Several species display brilliant yellow foliage in the autumn, examples of which are shown on the page In praise of the colour yellow.

The generic name is the classical Latin word for poplars. The common name cottonwood alludes to the fluffy seeds. The name aspen is derived from Old English æspe, originally from Proto-Germanic aspe (‘shaking’), alluding to the fluttering leaves of European aspen (P. tremula).

In autumn, the foliage of this iconic species adds vivid splashes of yellow to numerous montane areas in western North America.

The leaves of these plants have a dense layer of golden scales beneath, which gave rise to the generic name, derived from Ancient Greek khrysos (‘gold’) and lepis (‘scale’). The fruit is very spiny, a so-called cupule, containing three edible nuts, which were a common food of indigenous peoples, raw or roasted.

The name chinquapin also refers to the related genera Castanopsis and Castanea. This word is a corruption of an Algonquian word, chechinquamin or chincomen, possibly from xinkw (‘great’) and mini (‘fruit’).

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘evergreen’.

Originally, Helenium was the name of elecampane (Inula helenium), which, it was said, Helen of Troy planted on the island of Pharos.

The common name was given in allusion to the ancient usage of dried leaves to make snuff, which was inhaled to help sneezing, thus ridding the body of evil spirits.

The specific name was given in honour of surgeon and botanist John Milton Bigelow (1804-1878), who collected many new plant species on expeditions to south-western U.S. and northern Mexico.

American botanist, chemist, and physician John Torrey (1796-1873) found the colour of this plant so striking that he named it Sarcodes sanguinea, from Ancient Greek sarkos (‘flesh’) and the Latin sanguis (‘blood’), thus ‘the blood-coloured, fleshy one’. The common name refers to the early flowering of this species, which often appears, when snow is still partly covering the ground.

In his book The Yosemite (1912), Scottish-American writer and environmentalist John Muir (1838-1914) writes the following about this species: “The snow plant (…) is more admired by tourists than any other in California. It is red, fleshy, and watery and looks like a gigantic asparagus shoot. Soon after the snow is off the ground, it rises through the dead needles and humus in the pine and fir woods like a bright glowing pillar of fire. (…) It is said to grow up through the snow; on the contrary, it always waits until the ground is warm, though with other early flowers it is occasionally buried or half-buried for a day or two by spring storms. (…) Nevertheless, it is a singularly cold and unsympathetic plant. Everybody admires it as a wonderful curiosity, but nobody loves it as lilies, violets, roses, daisies are loved. Without fragrance, it stands beneath the pines and firs, lonely and silent, as if unacquainted with any other plant in the world; never moving in the wildest storms; rigid as if lifeless, though covered with beautiful rosy flowers.”

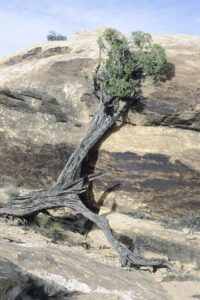

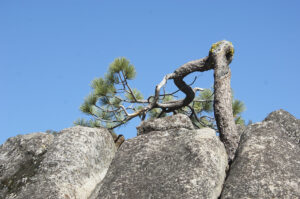

In favourable conditions, it may grow to almost 30 m tall, but at exposed locations it often becomes stunted and twisted.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘white-stemmed’ (i.e. ‘with a white trunk’).

These peculiar trees are restricted to high-altitude areas in eastern California, and in Nevada and Utah. Apart from certain clones, including a creosote (Larrea tridentata) in the Mohave Desert, whose age is estimated at c. 9,400 years, this pine is the oldest living organism on Earth, a few of them being around 5,000 years old.

The specific name is Latin, meaning ‘ancient’.

Other photos, depicting these remarkable trees, are shown on the page Plants: Ancient and huge trees.