Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Asia & Europe 1975: Long journey home

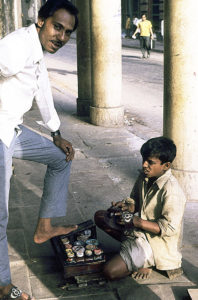

After experiencing the relatively civilized Southeast Asia, this metropolis is an overwhelming experience, displaying an entirely alien culture and religion. Everything seems utterly chaotic in this city, where trucks, busses, cars, motor-rickshaws, ox-carts, motorcycles, scooters, pedestrians, and sacred cows mingle in a seemingly hopeless tangle, but, almost miraculously, traffic is still moving, albeit at a snail’s pace. In Calcutta, you also notice the old-fashioned rickshaws – two-wheeled, open carriages, pulled by a man, who is running – most often barefoot – in front of the vehicle, holding on to two bars.

Poverty is appalling in this city, in which millions of people live without a roof over their heads. Instead, they stay beneath bridges, on railway embankments, or simply on the street, where busy people pass them, oblivious of their need. Countless Indian white-backed vultures (Gyps bengalensis) and Indian black kites (Milvus migrans ssp. govinda)* are soaring over the city.

Calcutta’s former name was Kolkata or Kalikata. In 1696, an Englishman, Job Charnock, who was working for the British East India Company, lead a group of traders up along the Hugli River, as they had been chased away from their original trading post by a local ruler. Now, further up the river, they constructed a new trading post, Fort William, near a couple of villages, of which one was named Kalikata, supposedly named after an old cultic shrine, dedicated to the Hindu goddess Kali. This name was distorted to Calcutta by the British.**

The original name of the city was Kashi, meaning ’light’, and as the city is situated at the river bank, facing east towards the rising sun, you may call it ’a city of light’. Its more recent name Varanasi is a combination of the names of two rivers, Varuna and Assi, which have their outlet in the Ganges at this spot. During the British colonial period, the name Varanasi was corrupted to Benares.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Varanasi was founded about 3,000 years ago. However, most of the present buildings are not particularly old, as the city has been destroyed several times during invasions by various peoples, including the Moghuls, a Muslim tribe from Turkmenistan, who conquered most of northern India. For about 300 years, they ruled this area. Especially during the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), who was a fanatic Muslim, many Hindu buildings were destroyed, including the Golden Temple in Varanasi, which was replaced by a mosque.

We roam the lanes of Old Varanasi, which are so narrow that cars cannot enter. What you encounter here are pedestrians, water buffaloes, sacred cows, and an occasional motorcycle or scooter. Loud shouting announces that a burial procession is on its way towards the Ganges. Many old or sick persons are brought here to die, later to be cremated on the banks of the sacred river. Following the cremation, their ashes are strewn on the river, increasing their chance of attaining moksha – liberation from the eternal sequence of re-incarnations. Moksha and other Hindu phenomena are dealt with in detail on the page Religion: Hinduism.

Eberhard plans to go to Bombay, while I want to leave this baking oven as quickly as possible. The train journey to the capital of India, Delhi, is a lengthy affair, so in order to avoid a trip similar to the one we experienced from Calcutta to Varanasi, where we had to sleep on the floor, I book a so-called ‘sleeper’. A Second-Class sleeper is just a plank bed with a thin cover, which you have the right to occupy during the night. I spread out my worn-out sleeping bag to announce that this place is occupied.

Vendors walk along the train, shouting, ”Chai! Chai! Garam chaiii!” (’Tea! Tea! Hot tea!”), carrying a large pot with hot, sweetened milk tea, and a sack filled with tiny cups, made from unburnt clay. The idea is that when you have finished drinking your tea, you just toss the cup out of the window, where it breaks on the ground, re-entering the cycle of nature. In this way, the vendor doesn’t have to return to collect cups.*

In the morning, I awake early, and during a stop at the next station, I leave the train to buy breakfast on the platform: puri, which is pancake-shaped loaves, fried in oil, until they pop up, served with tamarind sauce, and samosas – small, deep-fried triangles of dough, containing potato curry.

Refreshed, I can now concentrate on watching life on the immense, flat, dusty Ganges Plain. In the villages, houses are mostly made of clay and straw, often surrounded by groups of mango or fig trees, which cast long morning shadows. Beneath these trees, in the shade, village men will gather in the evening after a long day’s work to talk and smoke a bidi (a ‘poor man’s cigarette’, made from the leaves of a tree, Diospyros melanoxylon). Carts, pulled by oxen, move at a snail’s pace along bumpy tracks, and the leaves in small bamboo groves rustle in the morning breeze. A flock of vultures are fighting with dogs over the remains of a dead cow. Many people are defecating on the railroad slopes, oblivious of the passengers watching.

Occasionally, we pass stinking industrial towns, where factory chimneys emit huge quantities of black smoke into the already misty landscape. Lots of vultures and kites are soaring over the fields, while gorgeous Indian rollers (Coracias benghalensis) take off from the thickets. Various birds are feeding in puddles along the railroad, such as black-winged stilts (Himantopus himantopus), pond herons (Ardeola grayii), and yellow-billed egrets (Mesophoyx intermedia).

Throughout its long history, Delhi has been a capital at least eight times, for example during the Muslim reigns of the Delhi Sultanate and the Moghuls, and later during the British colonial days, when the capital was moved here from Calcutta. Today, Delhi is the capital of the Indian Union.

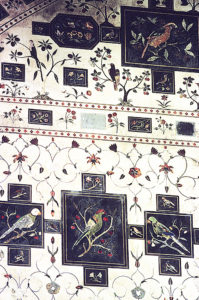

The city contains a huge number of marvellous buildings, but I concentrate on exploring two in Old Delhi. Here is an enormous fort, Lal Qila (‘Red Fort’), built in red sandstone. Construction was begun during the reign of Moghul Emperor Shah Jahan, completed in 1648. The entrance gates to the fort are very high, as the Moghul rulers wanted to be able to ride out through them, sitting on gorgeously adorned elephants, thus demonstrating their power. Divan-i-Am is a beautiful marble building, in which the emperor, seated on his famous peacock throne, would receive his subjects. Unfortunately, this building has been plundered several times and much of the original inventory stolen, including the peacock throne, the silver ceiling, and most of the vividly coloured, inlaid semi-precious stones. On the northern and southern walls is a famous inscription in Persian by poet Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), saying, “If there is a Paradise on Earth, it is this, it is this, it is this.”

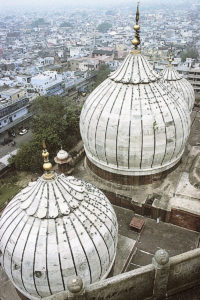

Not far from the fort is Jama Mashid (’Friday Mosque’), India’s largest mosque. Like the fort, its construction was initiated during the reign of Shah Jahan, completed in 1658. Friday prayer takes place on the 99-metre-wide main square, which is able to hold 25,000 people. Centrally on this square is a small pond, in which you wash your face, hands, and feet before the prayer. The mosque contains two minarets, both 39 m high. According to legend, a small building in the north-eastern corner of the mosque displays a footprint of the Prophet Muhammed himself.

Our journey brings us across the famous Khyber Pass, situated in the Spin Ghar Mountains. Formerly, almost all conquerors passed this way to enter the Indian Subcontinent, among these Persian kings Darius the Great (550-486 B.C.) and Mahmud of Ghazni, born Yamin-ud-Dawla Abul-Qasim Mahmud ibn Sebüktegin (971-1030), Afghan Muhammad Ghori, born Shihab ad-Din (1149-1206), Mongolians like Genghis Khan (c. 1162-1227) and Duwa (dead 1307), and Babur (’Tiger’), born Zahir ud-Din Muhammad (1483-1530), a Timurid prince of Turkic origin, who later became the first Moghul Emperor of India.

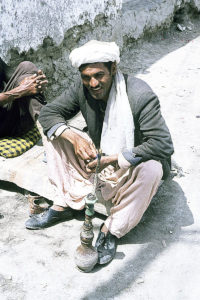

It is now mid-April, and a mild spring wind is blowing in Kabul, although the surrounding mountains are still covered in snow. I walk the streets of the city, taking in a new style of dress. The men all wear European-style jackets and long, loose trousers, making it more convenient for them to squat. Most men wear turbans, often consisting of a long, white cloth, folded numerous times around the head. Others wear small Muslim caps, often richly embroidered. Many of the women are completely hidden beneath a burka, a huge piece of cloth, which covers head and body, with a visor-like opening in front of the face, which makes it possible for the woman to find her way. The Holy Qur’an, Surah 33, verse 59, says, “Oh, Prophet! Say to your wives and your daughters and the women of the faithful to draw their outer garments close around themselves; that is better that they will be recognized and not annoyed. And God is ever forgiving, gentle.”

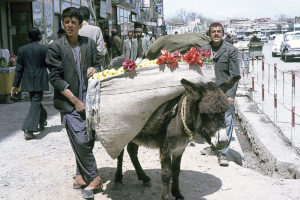

Motorized vehicles in this city mostly consist of busses and trucks, while private cars are remarkably few. Donkeys constitute a considerable part of the street scene, and several men are busy loading the animals with various items, including apples and garlic. In many places, tiny cages, containing various species of songbirds, such as calandra larks (Melanocorypha calandra), crested larks (Galerida cristata), goldfinches (Carduelis carduelis), and red-fronted serins (Serinus pusillus), are displayed for sale. Songbirds are popular pets in many Muslim societies.

Despite having only about a hundred thousand inhabitants, the desert city of Kandahar is spread over a huge area, as no house has more than two storeys. The bazaar is a lively and colourful spectacle, and among many other items, vegetables are sold here. To make them look more inviting, they are rinsed in water, running in the gutter. However, this water is extremely dirty, and I immediately lose any craving for raw salads! Meat products and sweets are displayed for sale, attracting thousands of flies, which swarm around the goods. I notice several blind beggars, who are probably suffering from trachoma, an eye disease transmitted by flies.

A few of the inhabitants differ from the majority by their Central Asian facial features. They are Hazara, a people who partly descends from immigrating Mongolians or Turks, who settled in Afghanistan around the 1200s. Even today, their language, and also part of their culture, differ from those of other Afghani tribes. Most Hazara are Shi’a Muslims, as opposed to the majority of the population who are mainly Sunni Muslims (see next caption).

In 681, Husain and his followers went to Iraq to fight against the Caliph of Damascus, who claimed that he was the true heir of Muhammad, selected by a council of elders. The Shi’a did not acknowledge this choice, maintaining that only God could appoint Muhammed’s heirs. In a battle at Karbala, Husain and his men were all killed, and from this day, the Caliphs of Damascus, and later Baghdad, held the power within Islam.

The Shi’a fervently commemorate the death of Husain. In his book Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern (Gloyer und Oldshausen, Hamburg, 1837, in English Travels Through Arabia and Other Countries in the East, Performed by M. Niebuhr, Gale Ecco, 2018), German cartographer and mathematician Carsten Niebuhr gives a vivid description of a group of pilgrims, paying a visit to the tomb of the martyr in Karbala, in present-day Iraq: “I was genuinely puzzled by watching the devotion, with which the superstitious people already in the front yard kissed the entrance door, and also later kissed the door of the mosque. Inside the temple, they eagerly kiss the floor, and I was told with conviction that to some devotees the death of Hössein is so sad that they hit their head against the wall and the iron grids. It has been told that some devotees have become so mad with rage that they have killed themselves at their great imam’s grave, believing that they will also be recognized as martyrs, and go to heaven, because they have given their life for the sake of Hössein. I must confess that I have never heard anything more plaintive than these devoted Shi’a. People screamed and howled as if Hössein had been their father and had been murdered this day; this was by no means false, like the professional mourners who weep over a deceased for money, but so genuine that the eyes of those who left the mosque were swollen from crying.”

In 818, the 8th imam, Ali ibn Musa al-Riḍha (in Iran known as Imam Reza), was murdered by order of the Abbasid Caliph, al-Ma’mun. The place he was buried was called Mashhad al-Ridha (‘Martyrdom of al-Riḍha’), and in the late 9th Century, a dome was erected on the grave. Later, numerous other buildings were built on this place, today constituting the largest Islamic temple complex.

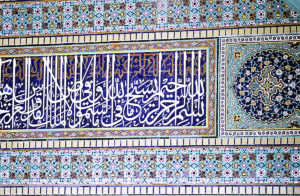

When I visit this mausoleum, the entire area in front of it is one huge construction mess. At the entrance, I learn that non-Muslims do not have access to the complex, but I am welcome to walk around it. On my walk along the outer wall, I can admire the wonderful tiles on it, adorned with Muslim inscriptions in beautiful calligraphy.

The following morning, I board another bus, headed for Tabriz and the Turkish border. The area around Tabriz is a lovely green, with poplars, in which rooks (Corvus frugilegus) are building nests, and wheat fields, where white storks (Ciconia ciconia) strut about. Yet another bus brings me along the huge Lake Van in south-eastern Turkey, a region known as Kurdistan. This area is inhabited by Kurds, a people with a sorry fate (see Travel episodes: Iran & Turkey 1973 – Kurdistan! Bum-bum-zip!). Birdlife is rich along the road, with species like lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni), ruddy shelduck (Tadorna ferruginea), European roller (Coracias garrulus), and woodchat shrike (Lanius senator). Small Anatolian ground squirrels (Spermophilus xanthoprymnus) sprint about along the road, and in case of any danger, they quickly vanish into their dens.

Formerly, the ibises in Birecik were held in esteem, as it was believed that the birds, when on migration, would guide Muslim pilgrims on their Hajj (pilgrimage) towards Mecca. Each spring, a festival would be held to celebrate the return of the birds. Despite this, its decline continued, and in 1972 only 26 pairs were breeding in Birecik.

At this point, a well-known Turkish bird painter, Salih Acar, his wife Belkis, and Udo Hirsch, a young German ethnologist and wildlife photographer, began their struggle to preserve the birds, for example by constructing artificial breeding platforms on the rock face above the town.*

Udo Hirsch once said, “Generations ago, the ibises built good, deep nests. Its eggs are very round, not oval, and roll easily. Today, the ibis nests in Birecik are nests only by courtesy. They are flat bunches of twigs, plastic-bags, and grass, and one good kick by a startled adult bird can easily throw an egg out of the nest and right off the ledge. The same is true of nestlings: as they squabble for food, the smallest are often bullied out of the nest, falling 40 feet.”

The first description and illustration of a northern bald ibis appeared in Historiæ animalium, Liber III, published in 1555 by Swiss physician and naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516-1565). He named it Corvus sylvatico (‘forest crow’), which in Old German became waldrapp – a name which has stuck to this day. The generic name is derived from the Greek gerón (‘old man’), referring to the bald head of the ibis, whereas the specific name is from the Greek eremía (‘desert’), alluding to the barren habitats of the species.

The wild population in Morocco is believed to be around 500, and the total number of birds in captivity is about 1,000. In Spain, the species was re-introduced in 2003, and today a growing population is breeding in the wild. In 2005, when I visited the Extremadura region of western Spain, I observed a bald ibis. I hardly believed my own eyes, as I had no knowledge of the re-introduction program, and this bird was indeed very far from the breeding colonies in southern Morocco!

My next goal is the small town of Çeşme, on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey, near the city of Izmir. During my stay in Sri Lanka, I met two Danes, Pia Rasmussen and Fritz Hansen, whom I stayed with for some time. They were planning to spend the spring on the Greek Island of Chios, and we agreed to meet there in May.*

However, when I arrive at Çeşme, I learn that the ferry to Chios has been cancelled for an unspecified period of time, due to tensions between the governments of Turkey and Greece. Consequently, I must travel north along the coast to the town of Çanakkale, where I board a ferry across the Dardanelle Strait.

While I trudge along the road towards the centre of Ivanic Grad, a car comes to a stop, and the driver informs me that I can sleep in his new house, which has not yet been fully completed. As it turns out, he has already had a fair share of drinks, but nevertheless makes a stop at a restaurant, where we meet some of his friends who offer more drinks. After some time, I am not quite sober myself. On our way towards the man’s house, his reaction speed has now been reduced to a degree that he forgets to turn at a road bend, causing the car to slide sideways into the ditch. This doesn’t bother him much. He gets hold of some friends who can pull his car out of the ditch, and we continue our journey to his house, where he bids me good night.

The following morning, I get a lift to Zagreb, but, unfortunately, I am dropped at a place with a long queue of cars. I trudge along the road, but then I am lucky again. A car comes to a stop, and the driver asks me if I want a lift to Germany! He is a young Turk, who is in a hurry to go back to Germany, where he is working. His father, who didn’t go back to Turkey on holiday, has fallen sick. The young man already has two other passengers, one of whom I met previously in Pakistan. By contributing a small amount for petrol, I get a lift the rest of the way through Yugoslavia and most of Austria.

On my way, I notice flowers like Christmas rose (Helleborus niger), alpine snowbell (Soldanella alpina), spring gentian (Gentiana verna), and alpine butterwort (Pinguicula alpina). The Christmas rose, also called black hellebore, is among the earliest flowering plants of the Alps, sometimes appearing in winter, as the name Christmas rose implies. Incidentally, the species has nothing to do with roses, as it belongs to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae). The generic name of snowbells, Soldanella, is a diminutive of the Italian word soldo (‘coin’), thus ‘little coins’, referring to the leaf shape of most of the 15 species of this genus.

The mentioned species and many other alpine plants are described on the page Plants: Flora of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

Birdlife in this area is scarce at this time of the year, but I do observe ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus), water pipit (Anthus spinoletta), and alpine accentor (Prunella collaris).

When I reach the pasture huts on Rinnberg Alm, snow is still covering the ground in most places. The door of a wood shed is unlocked, so I decide to spend the night in it. There is a very fine view from a ridge, and I look forward to enjoy the morning sun in this lovely place. But alas, when I wake up the following morning, the mountains are hidden in clouds, with a cold wind blowing. I quickly pack up, returning the way I came.

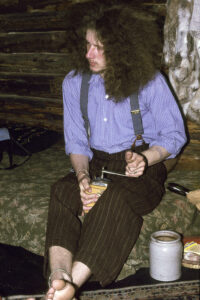

His name is Dieter, and he and his wife make a living from picking up all sorts of things, for instance from estates of deceased persons, which nobody else wants, selling the most useful items at flea markets in Frankfurt. They live in a small farm house in the village of Wittelsberg, and Dieter kindly invites me to stay with them for a couple of days. Here I meet his wife, Judith, who is likewise very friendly. Their home is an unbelievable collection of things, which most people would call old rubbish, but a cozy and happy atmosphere prevails here, so I spend a few lovely days with the family, before taking to the road again. On May 14, I am back in Denmark, 39 days after leaving Kuala Lumpur.