Kaj Halberg - writer & photographer

Travels ‐ Landscapes ‐ Wildlife ‐ People

Sri Lanka 1976: Among alcohol brewers

A water monitor lizard (Varanus salvator), almost 1.5 m long, emerges from the bushes along the shore, its forked, blue tongue continuously flicking out and in to smell the surroundings. The children chase it away, shouting. People here don’t like monitor lizards, because they eat chickens. On islets in the lake, flying foxes (Pteropus medius) – large fruit-eating bats – begin leaving their day-roost in the trees, which are taken over by cattle egrets (Bubulcus coromandus) and noisy house crows (Corvus splendens).

A pointed mountain in the distance is Adam’s Peak, which is sacred to followers of three religions. On its summit is a depression, shaped like a footprint. Christians and Muslims alike maintain that Adam made this footprint, when he and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden after The Fall. Buddhists claim that the Buddha made the footprint when he, according to legend, visited Sri Lanka.

The sun sets over the lake, and in the east a Full Moon is rising, its light reflected in the palm leaves. An Indian porcupine (Hystrix indica) passes by, its quills making a rattling sound. A collared scops owl (Otus bakkamoena) emits its piping call numerous times. From far out on the lake, you hear fishermen singing, their lamps blinking in the dark.

Padmasiri and his wife Kusuma have three sons, Lasante, Chamare, and Surange, between three and ten years old. They also had a daughter, but she drowned in the lake a few years prior. Not only the five of them live in the house, but also three relatives, Padma’s sister Daya (who, incidentally, owns the house, as Padma is not able to save any money), and two nieces, Reluka and Shamini. Thus, the house is rather crowded, but nevertheless they vacate one of the rooms for me to stay in. Padma and Daya speak a little English, so they act as interpreters for me. If a subject has to be discussed in detail, I usually go to a teacher’s house down the road.

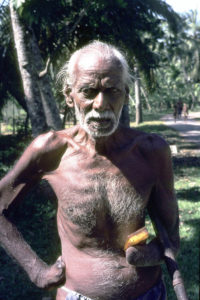

All year round, it is very hot and humid here. Around their waist, men wear a length of cloth, a sarong, about 1 m long. Besides a sarong, women wear a tiny blouse, covering their breasts. Young girls and some women wear a European-style frock. Boys only wear shorts, small children often nothing at all. When men go to town, they wear a shirt and shoes, while women dress in a fine sari, a length of cloth, wrapped around the body in a way that I am never able to comprehend.

Around their house, the family cultivates various plant species that are typical for this region of Sri Lanka. The most important of these is the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera), which produces ripe nuts approximately every second month year-round. Copra is an ingredient in nearly all meals here.

Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) is similar to breadfruit (A. altilis), but is much larger. The native area of this species is unknown, but is thought to be somewhere in Tropical Asia. Today, it is only known as a cultivated species. Its fruit, comprising hundreds, or even thousands, of individual flowers, may reach a length of 90 cm and weigh as much as 50 kilos. It grows directly on the trunk, and a mature tree can produce 100 to 200 fruits a year. Below the knobbly outer layer of the fruit is a whitish mass, surrounding the nut-like seeds. Both are delicious when boiled. A slightly acid layer around the nuts can be eaten raw.

The mango tree (Mangifera indica) has ripe fruits once a year, an important source of vitamins and minerals. The small fruits of the cucumber tree, or bilimbi (Averrhoa bilimbi), also supply lots of vitamin C, and they are also used in juices and chutney. The juice is efficient in cleaning metal pots. Bilimbi is a close relative of the star fruit (Averrhoa carambola), which is widely cultivated for its edible fruits. (A picture of this fruit may be seen on the page Silhouettes.)

The betel palm (Areca catechu) is also cultivated for its fruits, but for an entirely different reason. The hard nut is cracked into small pieces, which are mixed with tobacco, spices, and a little lime, whereupon these ingredients are wrapped in a leaf from the betel vine (Piper betle). This mixture is chewed for some time, increasing the production of saliva and causing a mild intoxication. The habit of betel chewing is evident everywhere. Walkways, house walls, and even stairs are full of red stains, left by betel-chewers.

Tubers like manioc, or cassava (Manihot esculentus), and taro (Colocasia esculenta) are cultivated beneath the trees, as are various vegetables.

Padma employs two different methods for catching fish. Mats are made from split, 1.5-metre-long, thin bamboo stems, tied together with string at the upper and lower ends, and in the middle. These mats are tied to poles, which are stuck into the lake bottom, forming two rows. The space between these rows gradually decreases, ending in a fish trap. During the day, fish are attracted by fodder, and at night by kerosene lamps, tied to the poles. The traps are emptied every morning and evening.

Employing the second fishing method, Padma places a large pile of branches in an area of shallow water, after which he pours fish fodder into the pile. After dark, he and a helper paddle out on the lake, bringing along a 10-metre-long bamboo mat, placing it in a circle around the pile of branches – as silently as possible, so as not to scare the fish away. The following morning, Padma puts on a loincloth, takes off his sarong, and enters the circle, in which he throws all the branches over the edge of the mat, making a new pile beside it. Sometimes, during this procedure, some of the larger fish manage to escape by jumping over the edge.

After removing all the branches, Padma moves into the centre of the circle, beating the water violently to scare the fish out along the mat, whereupon he moves a net, tied to an egg-shaped frame, along the mat, near the lake bottom. Occasionally, he stops to take out the catch from the net. After ten to fifteen rounds, most of the trapped animals have been caught, the mat is taken down, and the entire procedure can be repeated.

Besides fish, Padma often catch shrimp and spiny lobsters. He and his family eat some of the catch, but the major part is taken to the market in a nearby town, 3 km away. A couple of times Padma has caught small marsh crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) in his trap. In former times, huge, man-eating crocodiles were living in the lake, but they have long since been eliminated.

Padma gets up around four o’clock to bring out bread. The other family members sleep a couple of hours more, whereupon the women start preparing breakfast in the kitchen – a tiny outhouse, the walls of which consist of bamboo mats, with a layer of clay applied, while several layers of palm-leaf mats constitute the roof. The fireplace is at one end of the kitchen, built of bricks, with other bricks to place the pots on. Most of these are clay pots, blackened by fire, while a few are aluminium. Water for cooking and drinking is brought from the well, situated c. 25 m away.

Rice is the main staple in Sri Lanka, served with curries, i.e. vegetables, fish, or meat, cooked with copra, chilies, and various spices. The chili grinder and the coconut scraper are two important tools in a Sri Lankan kitchen. The spicy chili is an ingredient in most courses. Unripe, green chilies are cut into bits and served raw, leaving a burning sensation on the lips, while ripe, red chilies are ground on the grinder – a flat, smooth stone, which is a bit higher at both ends. The chilies are placed on this stone and ground with a stone roll to a soft mass, which is added to the courses.

Daya splits a green coconut on an iron spike to remove the outer, tough layer, afterwards cracking open the nut itself with a heavy knife, collecting the milk into a small bowl. She then brings the two coconut halves to a coconut scraper, a small wooden board with a bent iron piece attached to one end. The free end of the iron is flat, with very sharp spikes. On this iron, the copra is scraped into small bits, which are then pressed to extract the oil. Copra and oil are cooked with the curries. The scraped copra can also be eaten raw, mixed with raw onion, lemon juice, salt, and chili powder. This mixture is called sambol.

For breakfast, the women often prepare indiapa – a type of very thin rice noodles. They are made by pressing dough of wet rice flour trough a pipe with numerous tiny holes at the end. A suitable amount is pressed onto tiny woven mats, which are then placed on top of each other and steamed for four or five minutes. Before eating indiapas, you often dip them in sambol.

When the boys have finished their breakfast, Lasante and Chamare go to school, wearing their school uniform: blue shorts and socks, white shirt, and brown shoes. Their mother hands each of them a small metal box, containing their lunch of rice and curry. Little Surange is playing all day long with his puppy or with other small children in the village.

Padma returns from his job at the bakery, and after eating breakfast he paddles out to collect his nightly fish catch. Meanwhile, the women clean the house and the yard, after which they go to the well to have their morning bath. Kusuma collects some palm leaves, which have been soaked in the lake for days. Using a large knife, she splits the leaves along the midrib, whereupon Reluka starts weaving mats from the halves. She bends every second leaflet backwards, weaving it into the ones, which remain in their natural position. During this process, the leaves must be wet, as the leaflets will otherwise break. The finished mats, measuring c. 1.5 x 0.5 m, are mostly used as roof cover.

Now Padma returns with his catch and proceeds to clean the fish, scraping off the scales, taking out the guts, and cutting off the fins. One foot holds the knife steady, the sharp edge upwards, leaving both hands free to do the work. The fish are cut into smaller pieces and cooked with herbs and chili. Meanwhile, the rice has been cooked, and soon we can enjoy a delicious lunch.

Padma takes a well-deserved nap, together with Surange and the dogs, while the women clean the kitchen. When he wakes up, Padma rides to town on his bicycle to sell the fish, which were not consumed. On his way, he also collects payment for the bread he delivered in the morning.

The Fernandos are Buddhists. In the evening, Daya approaches a small niche in one corner of the living-room, in which a small, golden statue of the Buddha is placed. She puts fresh flowers in a bowl of water, whereupon she lights two small oil lamps and two incense sticks. For a minute or so, she silently venerates the Buddha, hands cupped in front of her face.

By now, I am regarded as a family member, and Padma has gained some confidence in me. He admits that he, in fact, has a third job. When I ask him, what that job might be, he is somewhat secretive, telling me to join him out on the lake, paddling towards an islet. On our way, we pass a huge raft, c. 50 m long, consisting of numerous tree trunks, which are tied together. Six men are punting this ‘vessel’ towards the coast, and today is their third day of this amazing task. At night, they must stop, as the Moon is new, and the raft is very difficult to manoeuvre in the dark. On the raft, the men have constructed two small huts, in which they cook and sleep.

When we reach the islet, Padma guides me into a dense patch of bushes. Hidden in here is a large oil drum, placed on a roaring fire, a long glass tube sticking out of it. It wheezes and bubbles inside the tube, from which kasippu, home-brewed alcohol, is dripping into a smaller container. A small group of men are busy pouring the alcohol into bottles, which are then smuggled to the opposite lake shore to be sold there. I am informed that one of their customers is the local policeman! Padma confides in me that this activity is very profitable – much better than fishing. I believe him. The process requires only sugar, yeast, and water.

I am offered a glass of the brew, which is probably pure wood alcohol – awful stuff, which kicks worse than a horse. After a couple of drinks, I feel rather dizzy, and on our way back to Padma’s house, I laugh like a fool, babbling to some of the brewers who paddle next to us. By now, I am so drunk that they appear to have two heads!