Cattle, banteng, and yak

Zebu cattle and trees, reflected in the ancient moat, which surrounds the Angkor Wat temple complex, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wait for me! – Bringing home her family’s cattle shortly before dusk, this girl is pulling a cow while holding on to another cow’s tail. Usually, cattle owners in the Himalaya do not let their animals graze out at night for fear of attacks from wolves or bears. – Kaza, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

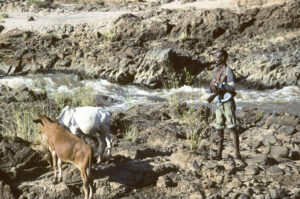

Well-armed cattle herder, carrying an automatic gun, Dawa River, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grazing cattle, Oudtshorn, South Africa. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Illuminated by late afternoon sunshine, this little Oromo herder is driving home his family’s cattle, Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This ox-cart, pulled by decorated zebu oxen, is ready to bring tourists to a hotel in Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

”You certainly don’t want to kill your mother who provides you with milk.”

Orthodox Hindu, commenting on cattle slaughtering.

The name aurochs means ‘the original ox’ in German. This magnificent animal was formerly called Bos primigenius, but is today often referred to as Bos taurus ssp. primigenius. It was once widely distributed in Eurasia and North Africa, comprising three subspecies, primigenius, which was native to Europe and the Near East, namadicus, which lived in the Indian Subcontinent, and africanus, which was restricted to northern Africa.

An old description of the aurochs is given in Commentarii de Bello Gallico (‘Commentaries on the Gallic War’), by Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 B.C.): “There is a (…) kind of animal, which is called the ure-ox. These German oxen are a little below the elephant in size, and of the appearance, colour, and shape of a bull. Their strength and speed are extraordinary. They spare neither man nor wild beast whom they have espied. The Germans take much pains to trap them in pits and kill them. The young men harden themselves with this exercise and practice themselves in this sort of hunting, and those who have slain the greatest number of them, having produced the horns in public to serve as evidence, receive great praise. But not even if they are caught when they are very young, can these oxen be accustomed to people, and tamed. The size, shape, and appearance of their horns differ much from the horns of our oxen. The Germans eagerly search for these horns, bind their tips with silver, and use them as cups at their most sumptuous entertainments.”

The aurochs was eradicated by hunting. The last ones in the wild lived about 500 years ago.

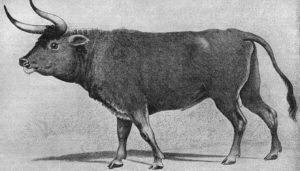

Aurochs. – Drawing from the 16th Century. (Public domain)

Petroglyphs from the Bronze Age, depicting aurochs, Bohuslän, Sweden. It seems that one of them is tossing a man about. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Early domestication

Archaeological evidence indicates that cattle were first domesticated from the aurochs in south-eastern Turkey and western Iran about 8,500 B.C., and in Europe they arrived roughly at the same time as agriculture, i.e. around 6,400 B.C. These cattle later evolved into today’s taurine cattle.

Domestication of the eastern subspecies of the aurochs, ssp. namadicus, took place about 6,000 B.C. in the Indus Valley. These domesticated animals evolved into today’s zebu, with its characteristic hump. From the Indus Valley, this breed was brought to practically all warmer areas of Asia, including China, Southeast Asia, and Indonesia. Around 2,000 B.C., it arrived in Africa. Today, it is also found in tropical areas of the Americas. (Source: Ajmone-Marsan et al. 2010)

There is a far cry between the mighty aurochs, which was first tamed in the Middle East about 10,500 years ago, and today’s scrawny cattle of the same area. – Ploughing with bullocks, Luristan, Iran. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wall painting from the 15th Century B.C. in Djeser-Djeseru, or the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Luxor, Egypt, depicting gifts for the Egyptian Pharaoh: A cow and various birds. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This relief from the 12th Century B.C., displayed in the Death Temple of Ramesses III, Valley of the Kings, Luxor, depicts an enormous zebu bull, and farmers at work. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Complicated ancestry

Traditionally, cattle were classified as belonging to three separate species: the aurochs (Bos primigenius), the European taurine cattle (B. taurus), and the Asian zebu (B. indicus). However, recent DNA research has revealed that the aurochs is ancestral to the zebu as well as the taurine cattle, and they have been re-classified as a single species, Bos taurus, with three subspecies: taurus (taurine cattle), primigenius (aurochs), and indicus (zebu).

Further complicating the matter is the ability of taurine cattle and zebu to interbreed, and sometimes have fertile offspring, with closely related species of oxen, including yak (Bos grunniens), gaur (B. gaurus), banteng (B. javanicus), American bison (B. bison), and Eurasian bison, or vicent (B. bonasus).

Taurine cattle (Black Angus), near Wellsford, North Island, New Zealand. The bush with yellow flowers is common gorse (Ulex europaeus). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

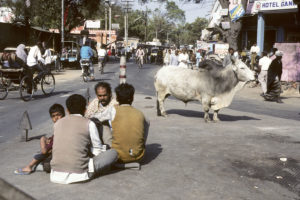

Zebu ox in the city of Pushkar, Rajasthan, India. Note the northern plains langur (Semnopithecus entellus) in the background. This monkey is described on the page Animals – Mammals: Monkeys and apes. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Etymology

The generic name Bos is from the Greek boûs (‘ox’), derived from Sanskrit gaús, plural go. The specific name taurus is Latin for ‘bull’, derived from Proto-Indo-European tawros.

Originally, the word cattle was not applied only to oxen. It originated from Anglo-Norman catel, derived from medieval Latin capitale (‘money’, ‘capital’), which originated from caput (‘head’). In those days, the word cattle covered movable property, especially livestock of any kind, as opposed to real property, the land. The term replaced the Old English word for cattle, feoh, derived from Gothic faihu, which originally also meant ‘property’.

The word cow is a corruption of Anglo-Saxon ku, which was derived from Sanskrit go, which is again derived from Ancient Indo-European gous (‘ox’). In Scotland, a cow is a coo or cou, plural kye, probably terms that came with the Viking invasions.

Driving cattle along the road to their grazing ground, Stubach Valley, Hohe Tauern, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

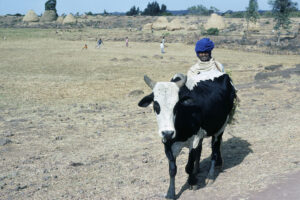

Farmer with his cow, Bahir Dar, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Some cattle facts

Terms for various ages and sexes of oxen include bull, which is an uncastrated male, whereas a castrated male is a bullock, in the United States a steer. A female, which has been calving, is a cow, in the strict sense, whereas a young female, which has not yet had a calf, is a heifer. Young of both sexes are called calves.

Evening light on heifers, grazing on an islet in Roskilde Fjord, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Heifers are usually very curious. If you lie down in their grazing field, they will surely come and sniff to you. – Jersey cattle, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Calves of Scottish Highland cattle, Öland, Sweden (top), and Bornholm, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

When a bull intends to find out whether a cow is in heat, he sniffs her vagina or her urine, whereupon he rolls back his lips in a grimace, called flehmen. A sensitive area in his mouth can detect, if the cow is producing certain hormones, which reveal that she is in heat.

After sniffing a cow’s vagina, this bull performs flehmen, Sauraha, southern Nepal. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The gestation period of cattle is about 283 days. A newborn calf typically weighs between 25 and 45 kg.

Cow with new-born calf, Fanø, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Patting a four-day-old calf, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The oldest cow on record was Big Bertha, born in Kerry, Ireland, in 1945. She died in 1993, at the ripe age of 48. She appears twice in Guinness Book of World Records, one for being the oldest cow recorded, and another for being the cow which produced most calves – no fewer than 39. (Source: irishpost.com, Jan 24, 2017)

Usage of cattle

Originally, cattle were utilized for meat, and later people learned to appreciate their milk. The wheel was invented in the Middle East, maybe as early as the 4th Century B.C., and the first carts were probably drawn by cattle. Today, ox carts are still a common sight in some Asian and Latin American countries, usually pulled by bullocks, which are easier to control than uncastrated bulls.

At an early stage, oxen were also utilized to pull the plough, and to work on so-called bucket chains, or pot garlands, in which buckets or pots are attached to a turning wheel, scooping up water from wells and emptying it into irrigation canals.

Various leather items were made from cattle hides, including clothes, shoes, belts, and straps, the latter three still being produced today. At an early stage, cattle dung was utilized as fuel, and later as manure.

Beef cattle auction, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

At an early stage, people learned to appreciate cow milk. These women in the city of Jaisalmer (top), and in the village of Bambara, Rajasthan, India, is milking their zebu cows. The calves are waiting to get their share. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Old-fashioned stables are a rare sight in Europe nowadays. These pictures show dairy cattle, a crossbreed between Danish Red and Brown American, at Peder Thellesen’s farm near Bramminge, Jutland, Denmark, 2013. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The first carts were probably drawn by oxen. This Khmer relief in the Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia, depicts an army on the march, with a cart, pulled by a zebu ox. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cart, pulled by zebu oxen, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

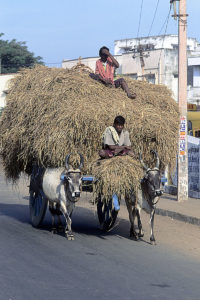

These zebu appear like midgets beneath a huge load of straw, Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, South India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Still today, ploughing with bullocks takes place in many parts of Asia. This man near Pre Rup, western Cambodia, is ploughing his paddy field, using zebu oxen. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Farmer, ploughing a field with oxen, Pokhara, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In many parts of the Himalaya, ploughing the narrow terraced fields is done with the help of small, agile oxen. This picture is from the Tamur River Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Today, bucket chains, or pot garlands, which scoop up water from wells, are a rare sight. This one, driven by zebu oxen, was seen near Mount Abu, Rajasthan, India, in 1991. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This ox-driven press near Mount Popa, Myanmar, extracts oil from peanuts. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In this picture from Ranthambhor, Rajasthan, India, cattle dung has been formed as ‘cakes’. They are now drying in the sun, later to be used as fuel. Dried ‘cakes’ have been stacked to the right. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In certain areas of Latin America, cowboys working on horseback may still be encountered.

Cowboys, driving cattle along a road, Cordillera de Guanacaste, Costa Rica. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bullfighting

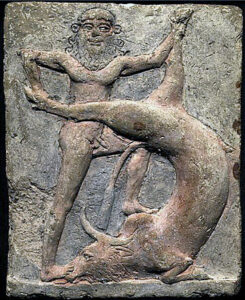

This specialized usage of cattle has its roots in bull worship and sacrifice in prehistoric Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean region. The first recorded bullfight may be found in the Epic of Gilgamesh, a collection of poems from Mesopotamia, which is regarded as one of the earliest surviving examples of outstanding literature. The beginning of this epic is five Sumerian poems, dealing with Gilgamesh (or Bilgamesh in Sumerian), a king of Uruk, ruling during the Third Dynasty of Ur, around 2100 B.C.

One episode in the epic describes, how Gilgamesh and Enkidu fought and killed the Bull of Heaven: “The bull seemed indestructible. For hours they fought, until Gilgamesh, dancing in front of the bull, lured it with his tunic and bright weapons, and Enkidu thrust his sword deep into the bull’s neck, and killed it.” (Source: Ziolkowski 2011)

Modern-day bullfighting is a kind of contest, involving a man, in Spanish called a matador de toros (‘bull matador’), who attempts to subdue, immobilize, and kill a bull, usually according to a set of strict rules. The bulls utilized in Spanish-style bullfighting are bred for their aggression and physique, raised free-range with little human contact. (Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bullfighting)

This ancient Mesopotamian terracotta relief from c. 2250-1900 B.C. shows Gilgamesh slaying the Bull of Heaven. (Photo: Public domain)

Bullfighting, Sevilla, Andalusia, Spain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle breeds

Over time, more than 1,000 cattle breeds have evolved around the world.

Hereford

This breed originated in the county of Herefordshire, England, in the 18th Century. By the end of the century, its characteristic white face had been established, and the present colour markings evolved during the 19th Century. Hereford have been exported to many countries, and their present number is estimated at over 5 million.

The white head of Hereford cattle is one of their characteristics. – Møn (top), and Jutland, both in Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Friesian

Friesians, or, strictly speaking, Holstein-Friesians, are an ancient breed of dairy cattle, believed to have been selected for dairy qualities during about 2,000 years. They are famed for their extremely high yield of milk, which, however, has a relatively low butterfat content.

In their present form, Friesians originated from the Dutch provinces of North Holland and Friesland, and Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. Today, however, they are widespread in lowland Europe, where local breeds have often evolved. In the United States, this breed outnumbers all other dairy breeds, producing about nine-tenths of the milk supply. (Source: britannica.com/animal/Holstein-Friesian)

Danish breed of Friesians, chewing their cud, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Jersey

The Jersey is a British breed of small dairy cattle, originating from Jersey, one of the Channel Islands. Selective breeding has caused the milk production of these cows to increase to an average of 6,024 litres per year in the U.K., with some individuals yielding around 9,000 litres. The milk has a characteristic yellowish tinge and is high in butterfat (5.4%) and protein (3.8%).

As the Jersey adapts well to cold as well as hot climates, it has been exported to many countries around the world. Some countries have developed separate breeds.

Curious Jersey heifer, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scottish Highland cattle

As their name implies, these cattle originated in the Scottish Highlands, or maybe in the Outer Hebrides, first mentioned in the 6th Century A.D. In Scots, this breed is called Heilan coo, a name of Norse origin, meaning ‘highland cow’. They are characterized by their long horns and wavy coat, which comes in a variety of colours, including red, ginger, black, dun, yellow, white, or grey.

Today, Scottish Highland cattle are popular in many countries around the world, as their long coat allows them to be outdoors all the year round, even in harsh climates. They are raised primarily for their meat, which is prized for its low content of cholesterol, and also for the milk, which generally has a very high butterfat content.

Scottish Highland cattle, Jutland, Denmark (top), Bornholm, Denmark (2nd), Öland, Sweden (3rd), and Funen, Denmark. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scottish Highland bull, Funen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Scottish Highland cow and calf, Funen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

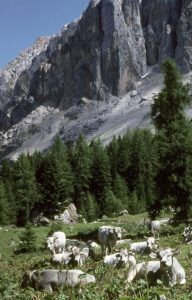

Black form of Scottish Highland cattle, Passo delle Erbe, Dolomites, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Angus

The Angus, or, strictly speaking, Aberdeen-Angus, is a breed of small beef cattle, descending from local cattle in the counties of Aberdeenshire and Angus, north-eastern Scotland, where they were first recorded in the 16th Century. This breed is very hardy and can survive the harsh Scottish winters outdoors.

The native colour of Angus is completely black, but a red form has recently evolved, and the udder may be white. Black Angus is the most common breed of beef cattle in the U.S., with 332,421 registered in 2017.

Black Angus is a popular breed in New Zealand. In this picture, a herd is being driven along a road near Kaitaia, North Island. Note the trained dog to the left. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Limousin

The Limousin is a breed of beef cattle, which originated in the Limousin and Marche regions of western France. The first reference to this breed dates from the late 18th Century. In those days, it was used mainly as a draught animal, but today it is reared for its high-quality beef, which is quite lean.

Suckling Limousin calf, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Galloway

A Scottish breed, named after the Galloway region of Scotland, where it originated in the 1600s. It is mostly black, but pied and white forms also occur. The muzzle is usually black. It has a thick coat, which is suitable for the harsh climate of Scotland. It is reared mainly for beef production.

White Galloway, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Braunvieh

The Braunvieh (‘brown cattle’ in German) derives from a local grey-brown mountain cattle, which was raised since medieval times in the Swiss canton of Schwyz. Today, it is distributed throughout the Alpine region. Originally, this breed had multiple usages: for milk production, for meat, and as a draught animal. Today, however, it is primarily a dairy breed.

Resting Braunvieh cattle, chewing the cud, Dolomites, Italy. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Braunvieh, Col du Pillon, Valais, Switzerland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dairy cattle, grazing on the extensive meadows of the Alps, are often adorned with bells, making it easy for the owner to find them at milking times. This picture shows a Braunvieh near Säntis, Sankt Gallen, Switzerland. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pied red cattle of the Alps

This cattle breed probably evolved partly from the Ennstaler Bergscheck (‘Ennstal mountain pied cattle’), an endangered Austrian breed.

Pied red cattle, and a single Friesian, grazing on a slope in the Rosanin Valley, near Thoma Valley, Austria. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This calf of pied red cattle is wearing a prominent nose ring, Rosanin Valley. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During a music festival, which took place in the village of Prägraten, Virgental, Tyrol, Austria, this orchestra was passing by a field with grazing pied red cattle. Initially, the cows were seized by panic (top), but soon their curiosity overcame their fear. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Danish Red

Formerly, Danish Red was the commonest dairy breed in Denmark. Today, however, the Friesian and the Jersey are more numerous. Danish Red evolved from cross-breeding local cattle with imported breeds. From old times, red animals occurred among local piebald breeds on the islands east of Jutland, but red only became dominant, when they were crossed with three imported breeds from Schleswig – all solid red.

Some of these animals were brought to Copenhagen, where they were being fed with the mash from beer and alcohol production. This fodder produced milk of high quality.

This picture shows a cross between Danish Red and Brown American, Jutland, Denmark. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Norwegian Red

Norwegian Red is a breed of dairy cattle, which was developed in Norway around 1935, by crossing foreign dairy breeds with several local breeds, including Norwegian Red-and-white, Red Trondheim, and Red Polled Østland. By the mid-1970s, Norwegian Red became the dominant breed in Norway, comprising 98% of the cattle population.

This Norwegian Red has rubber balls attached to its horns, Dovrefjell, Norway. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Texas Longhorn

This American breed is known for its characteristic horns, which may extend to over 2.5 m from tip to tip. It is descended from the first cattle introduced in the New World by Spanish colonists. As their original area in Spain was arid, these cattle have a high drought-stress tolerance. They can be any colour, but pied red-and-white is dominating.

Texas Longhorn, Pipe Springs National Monument, Utah. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

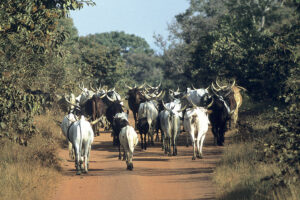

Ankole

This African breed is also characterized by the huge horns. It belongs to the broad Sanga cattle group and was probably introduced to eastern Africa 500-700 years ago by nomadic pastoralists from the northern part of the continent. Today, Ankole cattle are distributed in much of eastern and central Africa, particularly in Uganda, Zaire, Rwanda, Burundi, and parts of Tanzania.

A herd of Ankole cattle is driven along a road in Central African Republic. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Ankole cattle are characterized by their huge horns. – Mubende, Uganda. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Zebu

Zebu cattle originated from the eastern subspecies of the aurochs, namadicus, about 6,000 B.C. in the Indus Valley. Today, they are a very common sight in India, Pakistan, and Myanmar, and they are also quite popular in other tropical regions of the world, as they are more resistant to disease than European cattle breeds.

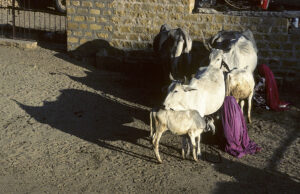

Zebu are characterized by a hump on their shoulder and a large dewlap. Most are white, but greyish, brownish, or blackish forms are sometimes seen.

A large herd of zebu cattle is driven across the Ayeyarwadi (Irrawaddy) River, Bagan, Myanmar. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Oblivious of the traffic, these multi-coloured zebu are chewing their cud on a bridge across the Parvati River, Himachal Pradesh, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Shoeing a zebu, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

After completing their working duties, Indian zebus are often released, roaming city streets and elsewhere.

For a number of years, this short-legged zebu bull constituted a part of the street scene in Jaipur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Do you have any goodies for me? – Inquisitive zebu, looking into a door-way, Jodhpur, Rajasthan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle in religious beliefs

Due to their long relationship with humans, cattle play a significant role in most religions. In former times, cattle were sacrificed during religious rites in many areas.

Animisme

To the ancient Asian animists, the ox was sacred, and it was often presented as an offering to gods or spirits. Still today, traces of this ancient practice are found in areas, where the dominant religion was the ancient animistic Bon. Even though this belief at an early stage was replaced by Mahayana Buddhism (Lamaism), you sometimes still encounter stone cairns in Ladakh and Tibet, on which horns of cows, yaks, or wild sheep have been placed as offerings. The horns and stones are often painted red, called Lato Marpo (‘Red Gods’), the red dye probably symbolizing blood from sacrificed animals.

These horns of yak and Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica), which have been painted red, are placed as offerings on cairns, Markha Valley, Ladakh. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This yak skull has been placed as an offering near mani stones (slabs with carved Buddhist mantras) on the kora, or pilgrim route, around Tashilhunpo Monastery, Shigatse, Tibet. Note that mantras have also been carved into the skull. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hinduism

In the Vedas, ancient Hindu scriptures, the cow is associated with Aditi, the mother of all the gods, and the cow is still sacred to Hindus, called Go Mata (’Mother Cow’). An orthodox Hindu will never kill a cow purposefully, and he will never eat beef.

Veneration of the cow arose in the Vedic Period, between 1,500 to 600 B.C. The Aryans, who invaded India around 1,500 B.C., were pastoralists, and the importance of cattle was reflected in their religion. Initially, Aryans sacrificed cattle and ate their flesh, but, over time, the slaughter of milk-producing cows gradually became prohibited. Parts of the great epic Mahabharata forbids it, and in the Rigveda, cattle are said to be ‘unslayable’. Panchagavya, the five products of the cow: milk, curd, butter, urine, and dung, are all used in rites of healing, purification, and penance.

When Hinduism took form, the cow was associated with various deities, including Brahma, Shiva, Indra, Krishna, and Yama. Shiva’s steed is the bull Nandi, whereas Krishna was a cowherd in his youth, and Indra is closely associated with Kamadhenu, the wish-granting cow, which is regarded as the source of all prosperity.

In one of the Puranas, the earth-goddess Prithvi milked the cow to generate crops for humans to end a famine, and, subsequently, milked it of beneficent substances for humans.

In Hindu mythology, the mount of the supreme god Shiva is a bull, named Nandi. – Khmer relief, Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This huge sculpture on Chamundi Hill, Mysore, Karnataka, India, depicting Nandi, was carved from a single block of granite in 1659. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This carving in a rocky river bed on the hill Phnom Kbal Spean, near Angkor, Cambodia, depicts Shiva and his consort Devi, riding on Nandi. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

To Vaishnavites, followers of the Hindu god Vishnu, the Muktinath Temple in Jhong River Valley, Mustang, central Nepal, is a most sacred site. In the Mahabharata, this place is called Salagrama, named after the fossilized ammonites (saligram in Hindi) – a group of extinct squid-like animals, which are often found in the river beds of this area, embedded in rocks. The spiral form of these ammonites causes Vaishnavites to regard them as sacred symbols of Vishnu’s chakra (disc).

Since ancient times, Muktinath has been the site of a temple, dedicated to Vishnu. From the barren landscape here, a sacred spring wells forth. Its waters are led in channels into the temple, where it is divided into 108 fountains, 105 of which are shaped like a cow’s head, the remaining three like a mythical, elephant-like creature. For devout Vaishnavites, a bath in these sacred waters will ensure that you obtain mukti (release from being reborn) after death.

Out of the 108 fountains at the Muktinath Temple, 105 are shaped like a cow’s head. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Today, the cow is venerated during various Hindu festivals.

To many Nepalese, Tihar, or Dipávali (’Festival of Lights’) is the most important festival of the year. According to legend, the death of a Nepalese king had been foretold by a sacred serpent. However, an astrologer predicted that the king might avoid death by placing a row of lamps, dedicated to goddess Lakshmi, from the entrance of the palace, leading to his bed. If the lamp in the doorway was extinguished, the king would die, and he could only be saved, if the serpent would beg for mercy from Yama, the god of death.

When the lamp was extinguished, the serpent approached Yama, who was entirely unaffected, marking a 0 at the king’s name in his register. However, the cunning serpent managed to add a 7 in front of the 0, thus prolonging the king’s life with 70 years.

To commemorate this miraculous gift, the king introduced an annual, five-day-long Festival of Lights, during which devout Nepalese show their gratitude towards Yama and Lakshmi. The most important day of this festival is Lakshmi Puja, in which the sacred cow is worshipped in the morning, as it is regarded as the visible form of the great mother-goddess Lakshmi.

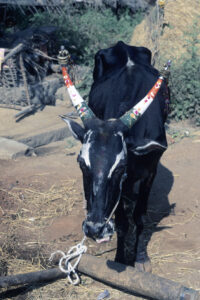

The cows are washed early in the morning, and their forehead, horns and tail are dyed with vermillion powder and turmeric. Mallas (garlands of marigolds) are draped around their neck, and they are fed with delicacies. People remove the sacred raksha thread from their wrist and tie it to the tail of a cow, begging it to guard their souls into heaven after death.

During the festival of Tihar, this cow has been adorned with mallas and bits of brightly coloured cloth. – Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Another Hindu festival, in which the cow plays an important role, is the South Indian Pongal, or Sankranti, which marks the beginning of the harvest. During this festival, cows are fed with pongal (a mixture of rice, sugar, lentils, and milk), after which they are washed in water, which has been dyed with turmeric powder, and their horns and hooves are painted in vivid colours.

During Pongal, celebrated in in Mysore, Karnataka, the horns of these zebu cows have been painted red, and some of them have been washed in turmeric water. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Judaism

In Ancient times, cattle were an important status symbol in Palestine, where a man’s wealth was measured by the number of cattle he owned.

Christianity

And the Lord said unto Noah: ”Come thou and all thy house into the ark; for thee have I seen righteous before me in this generation. Of every clean beast thou shalt take to thee by sevens, the male and his female; and of beasts that are not clean by two, the male and his female. Of fowls also of the air by sevens, the male and the female; to keep seed alive upon the face of all the earth. For yet seven days, and I will cause it to rain upon the earth forty days and forty nights; and every living substance that I have made will I destroy from off the face of the earth.” (Genesis, 7.1-4)

In Ancient Palestine, a ‘clean beast’ was any animal that would chew the cud and have a completely split hoof, i.e. cattle, sheep, goats, and other members of the family Bovidae, whereas ‘unclean beasts’ were other animals.

This mural painting in Kirke Stillinge Church, Zealand, Denmark, shows a ‘clean’ and an ‘unclean’ beast onboard Noah’s Ark: an ox and a donkey. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Christian evangelist Saint Luke is often depicted as a winged ox, or otherwise sometimes accompanied by an ox.

Stain-glass window in St. Dominic’s Church, Oyster Bay, Long Island, United States. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Daoism

During the Daoist festival Tzuoh Jiaw, celebrated in Taiwan, local gods are worshipped to prevent bad incidents. Other events, including pranks, also take place during this festival.

In this picture, Tzuoh Jiaw is celebrated in the village of Dalinpo, near Kaohshiung. Four men are performing as two fighting bulls, while two other men simulate a fight. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Cattle and environment

Although cattle are not seriously overgrazing areas, like sheep and goats do, they nevertheless have a heavy impact on natural areas around the world. Huge tracts of forest are cleared annually to create grazing grounds for the ever-growing number of cattle.

A herd of cattle is driven along the Rapti River, southern Nepal, causing huge amounts of dust to rise. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This herd of cattle is approaching a water hole in the Fuloha Oasis, Ethiopia, to quench their thirst. The trees in the background are doum palms (Hyphaene thebaica). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Banteng (Bos javanicus)

In former times, the wild banteng, also called tembadau, was distributed from eastern India and Southeast Asia southwards to the islands of Borneo and Java. This species has declined drastically, and today the total population of wild banteng may be as low as 5,000, its most important strongholds being on Java.

Banteng was domesticated at an early stage, and today the total population of domesticated animals is around 1.5 million, found mainly on Java and Bali. It has also been introduced to northern Australia, where feral populations constitute a threat to the local ecology.

Domesticated banteng are a common sight on Bali. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Indonesia, banteng bulls are utilized for racing, pulling a kind of wooden sledge, on which the coach is standing. These pictures are from the island of Madura. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yak (Bos grunniens)

The yak is a high-altitude species, which used to roam the Central Asian highlands in large numbers. It is adapted to a life in this harsh environment, having a luxurious fur, which keeps it warm in temperatures below -30o Centigrade. – A Nepalese legend, which explains how the yak got its rich fur, is related on the page Animals as servants of man: Water buffalo.

The yak was domesticated by nomadic tribes as early as c. 5000 B.C., and today the population is estimated at 14 million, the vast majority in Chinese territories. The population of wild yak may be fewer than 15,000, and though it is legally protected, illegal hunting still takes place and may threaten this magnificent animal with extinction.

The scientific name is Latin for ‘grunting ox’ – a most descriptive name, as it grunts incessantly.

At high altitudes in the Himalaya, yaks burdened with bulky loads are commonly encountered. – Gokyo Valley, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female yak, called nak, with calves, grazing near the village of Dingboche, Khumbu, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The nak yields excellent milk. In this picture, a man is milking a nak in the Upper Ghunsa Valley, eastern Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

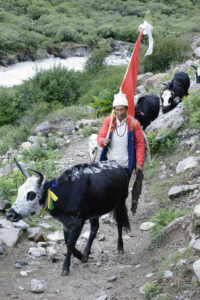

A dzopkio is a crossbreed between a yak and a lowland cow. It is used for transportation at lower altitudes in the Himalaya, as yaks do not thrive below 3,000 m, where they are vulnerable to diseases.

Dzopkios in an enclosure, constructed of rocks, Ghora Tabela, Langtang National Park, Nepal. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Decorated dzopkios are driven up into the Upper Langtang Valley, Nepal, on a day with ‘good luck’, predicted by a Buddhist monk. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

After a long day’s work, dzopkios and yaks are often released in the forest to graze. Whatever they can find of wild foods is supplied with hay, bought by the owner from local farmers.

This dzopkio is passing a mani-stone with carved Buddhist mantras, near the village of Ghat, Khumbu, Nepal. The plant to the left is Sikkim spurge (Euphorbia sikkimensis), which is avoided by grazing animals, as it is toxic. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

References

Ajmone-Marsan, P., J.F. Garcia & J.A. Lenstra 2010. On the origin of cattle: how aurochs became cattle and colonized the world. Evolutionary Anthropology 19: 148-157

Ziolkowski, T. 2011. Gilgamesh among us: Modern Encounters with the Ancient Epic. Cornell University Press

(Uploaded September 2017)

(Latest update October 2024)