Daoism

Dressed as one of the legendary San-tai-tze (‘Three Princes’), this man is dancing during a festival in Changhua, dedicated to the supreme Daoist Mother Goddess Mazu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the Boat Burning Festival, celebrated in Jiading, near Kaohsiung, a complete wooden boat is burned as an offering to Wang-yeh, the Daoist god of disease. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Yellow and red banners, carried in procession during the annual Mazu festival. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the annual Lantern Festival, volunteers undress to represent Handan-yeh, the Daoist money god. As he dislikes cold, people shell the volunteer with firecrackers to heat him up. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pictures on this page were taken in Taiwan, unless otherwise noted.

Daoism is one of the two great philosophical, religious, and ritual traditions of China, the other one being Confucianism.

According to legend, Daoism was founded by Chinese philosopher and writer Lao-tse (also written Lao-zi or Lao-tzu), lit. ‘Old Master’, who is regarded as the author of Dao-de-jing, which describes Dao as the root of all things, unseen and immensely powerful, yet supremely humble, the ideal of all existence. Reputedly, Lao-tse was born around the 6th century B.C., but some authorities claim that he is merely a legendary figure. In everyday religious Daoism, he is regarded as a deity.

Daoism does not emphasize strict rituals and social order, which are fundamental in Confucianism. Instead, it emphasizes living in harmony with Dao (literally ‘The Way’), i.e. according to ethic principles, focusing on simplicity and spontaneity, living a moral life, understanding the nature of reality, increasing longevity, and regulating consciousness and diet.

In the 4th century B.C., many Daoists began to emphasize living in accordance with the alternating cycles of nature, and, especially in southern China, absorbed many elements from shamanism (dealt with on the page Religion: Animism). To this day, shamans still play an important role in Daoist religious ceremonies.

The Mazu cult

According to legend, the supreme Daoist Mother Goddess Mazu was born in 960, in Fujian Province, southern China, as Lin Mon-yang, 7th daughter of Lin Yuan.

Her father and brothers were fishermen. One day, while they were out at sea, a typhoon struck, and the women feared that the men would perish. Mon-yang fell into a trance, during which she saw that her father and brothers were drowning, and she reached out to them, holding her brothers up with her hands and her father with her mouth. Mon-yang’s mother tried to wake her up, but she was in such deep trance that she appeared to be dead.

The mother, already convinced that the men had perished, broke down, crying. Mon-yang opened her mouth and let out a cry to let her mother know she was still alive, but this action forced her to drop her father. He perished at sea, but Mon-yang’s brothers returned alive. They related to the villagers that by some kind of miracle they had been held up in the water during the typhoon.

According to legend, Mon-yang died at the age of 28, when she climbed a mountain and flew to heaven to become a goddess, Mazu. After her death, many fishermen and sailors began to worship her, honouring her courage in trying to save those at sea, and the worship quickly spread to other Chinese coastal provinces. Much of her popularity stems from her role as a compassionate motherly protector.

When Chinese peoples from Fujian emigrated to Taiwan in the 17th Century, they, naturally, brought the Mazu cult with them. Today, there are more than 800 temples in the island, dedicated to Mazu.

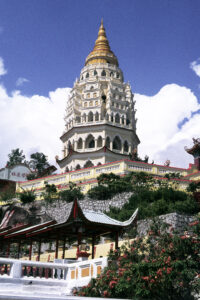

Today, Daoism is prevalent particularly in Taiwan, but Daoist temples are also found in China, Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia, and other countries with Chinese minorities.

Images of the Mother Goddess Mazu in the Grand Mazu Temple, Tainan (top), and in the Mazu Temple, Dongshih, south-western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Palanquin with a sculpture of Mazu, carried in procession during the Tiger God Festival, Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Other Daoist deities

In everyday Daoism, worship of gods is very common. There is a bewildering array of deities, guardians, and mythological figures, often depicted in temples and shrines.

Tu-di-Gong, the Earth God, is usually depicted as an old, white-bearded man, often in shrines along roads and on Taiwanese graves. (Pictures are shown on the page Culture: Graves).

Hu Ye, the Tiger God, is often depicted as a guardian in temples. He is celebrated with vigour during the annual Tiger God Festival (see below).

Guan-yin, the Goddess of Mercy, is immensely popular. She is the Daoist female equivalent of Avalokitesvara, the Buddhist Bodhisattva of Compassion. Her name loosely translates as ‘she who hears all humankind’s cries’ or ‘she who hears all sounds of the world’, and she is known to aid those who are suffering, and to work for the salvation of all beings.

The red-faced Guan Yu, also known as Guan Gong, was originally a military general, serving under the warlord Liu Bei during the late Eastern Han Dynasty (c. 25-184 A.D.). Among Daoists, he is regarded as a subduer of demons, revered as a deity for his righteousness, loyalty, and forgiveness.

Qingshui, known locally as Zushi-Gong, is the principal Daoist god worshipped at the Zushi Temple, situated in the town of Sanxia, northern Taiwan. This temple is popularly known as the ‘Bird Temple’, due to the numerous depictions of birds on walls and columns. Some of these are shown on the page Animals – Birds: Birds in Taiwan.

Tu-di-Gong is often depicted on graves, here in Taichung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Sculptures, depicting the Tiger God, Hu Ye, and his generals, Fushing Mazu Temple, Xiluo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In Vietnam, Guan-yin is often called ‘The Lady Buddha‘. She is depicted in this statue, 67 m tall, in the Linh Ung Pagoda on Son Tra Peninsula, Da Nang. The small boat in the foreground is a thung chai (basket boat), a type of coracle. Other pictures of this boat type are shown on the page Culture: Boats and ships. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

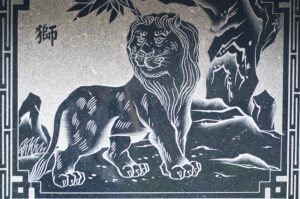

Supposedly, touching the head of this bronze lion, which guards the entrance to the Zushi Temple in Sanxia, northern Taiwan, brings good luck. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Offerings of incense sticks, bananas, money, and water have been placed at this shrine in Hanoi, Vietnam, dedicated to one of the Daoist mountain gods. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Temples and temple interior

Daoist temples are often extremely colourful, abounding with thousands of sculptures, paintings, reliefs, and other images. Many of the images depict various guardians, who protect against evil influences. The guardians on the temple doors are called menshen.

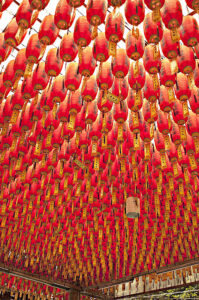

A very common feature is paper lanterns, often hung up in the hundreds on strings across the temple courtyard. A large collection of pictures, depicting such lanterns, is shown on the page Culture: Lamps and lights.

Most visitors to the temples place burning incense sticks in sand in thuribles, which are often guarded by dragons. Another very common practice is burning fake paper money as an offering in ovens, constructed in front of the temples.

Pagoda in the Kek Lok Si Temple, Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Detail of the colourful Gong Fan Temple, Mailiao. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Paper lanterns in a temple in Fengyuan (top), in the Fushing Mazu Temple in Xiluo (centre), and in Dongshih, south-western Taiwan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Temple guardian and paper lanterns in the Fushing Temple, Xiluo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These guardians, called menshen, are painted on a door, leading into a temple in Lugang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Qian-li-yan (‘He who sees far’, or literally ‘He of a thousand li’) is often placed as a guardian in Mazu temples, here in the Long Shan Temple (‘Dragon Mountain’), Lugang. A distance of 1,000 li (c. 500 m) was often used poetically for any great distance. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Temple guardian, Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Masks, depicting various benevolent guardians, Pitou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Modern temple guardian, driving a car during the Lantern Festival, Taitung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning incense sticks, Song Bo Chin Temple, Ershuei. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning incense sticks, Cihji Mazu Temple, Fengyuan. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning incense sticks, Long Shan Temple (‘Dragon Mountain’), Lugang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning incense sticks, Fushing Mazu Temple, Xiluo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Smoke from burning incense fills the air in the Zushi Temple, Sanxia. The stern guardians keep miscreants at bay. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Huge incense sticks in front of the Kuan Yin Teng Temple, Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning fake paper money, Pitou (top), and Changhua. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning a huge pile of fake paper money, Pitou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fruits and fake money, brought as offerings during the Mazu Festival, Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

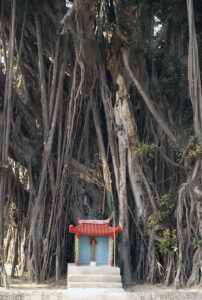

Daoist roadside shrines abound in Taiwan. This one has been erected beneath a large-leaved fig tree (Ficus superba), near Tainan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This roadside shrine near Rueilli is dedicated to the deity Tu-di-Gong (see caption Other Daoist deities above). (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dragon, feng-huang, and qi-lin

Sculptures, depicting these three mythological creatures, are ubiquitous in Daoist temples.

As opposed to the European mythology, in which the dragon is a fire-spewing monster, the dragon is a beneficial creature in Chinese mythology, a symbol of power, strength, and good luck, whereas the feng-huang (often erroneously called ‘The Chinese Phoenix’), who is the ruler of birds, symbolizes virtue, duty, mercy, and grace. As the masculine virtues of the dragon and the feminine virtues of the feng-huang complement one another, they are often depicted together in the temples.

The qi-lin is a mythological dragon-like creature, which however, is always depicted with hooves and a scaled body, often shaped like an ox, a deer, or a horse. It is a symbol of luck, good omens, protection, prosperity, success, and longevity, and although it may look fearsome, it only punishes the wicked.

Most Daoist temples abound with colourful images of dragons, Song Bo Chin Temple, Ershuei (upper 2), and Guang-fu-Gong Temple (‘vast fortune’), near Rueilli, a temple dedicated to Tu-di-Gong. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dragons on the roof of a temple in Da Nang, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dragons, and an unknown mythological figure, depicted on temples in Hanoi, Vietnam. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This fierce-looking, but cute dragon acts as an eye-catcher outside the Fushing Mazu Temple in Xiluo, where these women perform, singing traditional religious songs. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Wall painting in a temple, depicting a dragon, Miri, Sarawak, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These rather gaudy dragons, illuminated by neon light, are transported on a truck during the Mazu Festival, Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Images of the feng-huang also adorn most temples, here the Song Bo Chin Temple, Ershuei (top), and a temple on Lion’s Head Mountain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This feng-huang, observed in a temple at the Tran Quoc pagoda, Hanoi, Vietnam, is rather crane-like. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Temple decoration in Changhua, depicting a goddess riding on a feng-huang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This wall painting, depicting the feng-huang, was seen in Hau Lap, a Daoist temple built in 2012, Da Nang, Vietnam. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As the virtues of the dragon and the feng-huang complement one another, they are often depicted together on temples, in this case in Changhua. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The Moon is shining brightly behind sculptures on a pagoda in the Mazu Temple, Shingang, depicting a feng-huang and a dragon. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

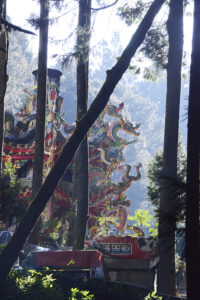

Morning sun illuminates the Shouzhen Temple in Alishan National Forest, central Taiwan, adorned with dragons and a feng-huang (beneath the dragons). The main deities worshipped in this temple are the male god Fude and the goddess Jhusheng. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This temple in Alishan National Forest is adorned with an elephant and a qi-lin. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This mosaic in the city of Da Nang, Vietnam, depicts a qi-lin. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion and tiger

Although neither the lion nor the tiger have ever lived in Taiwan, they occur abundantly in Daoist temples as mythological creatures, often in the form of guardians.

Outside many temples you notice sculptures, depicting male lions with a paw placed on a globe-like item, which, in fact, is an embroidered ball. In the old days, children presented balls, made from discarded clothes, as offerings to the temple – a symbol of yang (light forces) and friendship.

Lion sculptures are also often placed as protectors on Daoist graves. Several examples are shown on the page Culture: Graves

The presence of the tiger in Daoist temples is more easily explained than the presence of the lion. Daoism was brought to Taiwan from China, where the tiger was once quite common. In Chinese mythology, the tiger is the ruler of all animals, representing the masculine forces in nature. Traditionally, it is also regarded as one of the four super-intelligent creatures, the others being the dragon, the feng-huang, and the tortoise.

Ancient carvings, depicting lions, in the Shueisian Temple (built in 1780 and restored in 1812), Shingang (top), and in the Gong Fan Temple, Mailiao. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion sculptures, adorned with red ribbons, holding their paw on the embroidered ball, Donglong Temple, Donggang (top), Song Bo Chin Temple, Ershuei (centre), and Lion’s Head Mountain. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This lion, made from tiny bits of tiles, adorns the Donglong Temple in Donggang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Huge concrete lion, Siao Liouchou Island. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The ball of this giant lion in front of the Donglong Temple, Donggang, also functions as an oven, in which fake money is burned as an offering. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This lion is guarding outside the Guang-fu-Gong Temple (‘vast fortune’), near Rueilli, a temple dedicated to Tu-di-Gong. It keeps the ball in its mouth, instead of holding it with a paw. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion sculpture and incense sticks in front of a Daoist temple in Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion sculpture and incense sticks in front of the Kuan Yin Teng Temple, likewise in Georgetown. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This rather gaudy sculpture depicts a lion, guarding the entrance to a temple on Lion’s Head Mountain, northern Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These marble reliefs, encountered in the Guang-fu-Gong Temple (‘vast fortune’), near Rueilli, depict a lion and a tiger. This temple is dedicated to Tu-di-Gong. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This tiger adorns a temple in Beimen, dedicated to Wang-yeh, the God of Diseases. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Female tigers are often depicted with a cub, as here in the Fushing Mazu Temple, Xiluo (top), and in a temple in Lugang. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tiger, depicted on a wall painting at the entrance to a temple in Kuching, Sarawak, Borneo. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Daoist parades

A huge number of Daoist festivals are celebrated in Taiwan, all being immensely spectacular and colourful. Parades often take place during these festivals, where six or more men carry palanquins, containing images of Daoist gods, on bamboo poles, which rest on their shoulders. The palanquins are often decorated with flowers or other ornaments, and a huge number of firecrackers are ignited, often right beneath the palanquin.

Most Daoist parades include people with decorated faces, performing as devil-like figures, called Bajiajiang. They usually practice kung-fu during the parades. Other persons are hidden inside huge puppets, depicting various gods or guardians. They walk in a peculiar striding style, with swinging arms. Most Daoists regard these participants as persons being possessed by the various gods or spirits.

Tongji (or Jitong) are persons, who, as an act of repentance, often inflict wounds on themselves, using knives, spears, swords, or clubs with numerous spines.

During Daoist festivals, fireworks are always ignited, often beneath the palanquins, in this case during the Lantern Festival in Taitung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Colourful fireworks outside a temple in Beimen, dedicated to Wang-yeh, the God of Diseases. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

These tired men are resting in a pile of discarded fireworks boxes, Shingang. They are black in the head from forework smoke. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This palanquin, observed during a festival in Madou, near Tainan, is shaped like a huge crab-like monster. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This young man is being decorated as a Bajajiang, Taitung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dancing Bajiajiang, Donggang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During a parade in Taitung, these Bajiajiang practice kung-fu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bajiajiang, performing a dance in front of shops in Taitung, accompanied by music from brass horns and gongs. Supposedly, this act benefits the owner, i.e. he will make more money. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Bajajiang is blessing shop owners during a festival in Madou, near Tainan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Bajajiang with a trident, Beimen. In Daoism, the trident represents the Three Pure Ones, i.e. the universal energies, divided into the heavenly energy, the energy on the surface of the Earth, and the energy inside the planet. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Bajajiang in Taichung has been ‘adorned’ with huge tusks. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Huge puppets, depicting various gods or guardians, are steered by men, hidden inside the puppets. These were seen in the town of Beimen. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man, wearing a huge puppet outfit, participates in a procession during the Mazu Festival, Pitou. Note the peephole in the stomach. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This puppet is passing through exploding fireworks during the Mazu Festival, Pitou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man, wearing a puppet which depicts an old man whose face was scorched by fire, participates in a procession during the Lantern Festival, Taitung. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

In a trance, this Tongji on Siao Liouchou Island has been possessed by a god or a spirit. He has inflicted numerous wounds on his face and body – a common practice during Daoist festivals. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blood running down his face from self-inflicted mutilations, this Tongji is participating in a procession in Lugang. His cheeks have been pierced with a spear, to which people have attached money as a donation, expressing sympathy with his repentance. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This Tongji in Beimen, his face painted black, carries a club with numerous spines, with which he is going to inflict wounds on his back. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This pilgrim, participating in a parade during a festival in Madou, near Tainan, is dressed as Miss Piggy from The Muppet Show. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Neon lights constitute a part of modern Daoist parades, here in Madou, near Tainan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

The pilgrim in the picture below participates in almost all Daoist festivals, always walking in front, carrying a banner with an attached gong on which he announces the arrival of the procession. He always wears the same outfit: colourful straw hat, black dress with one long and one short trouser leg, red belt, white wool vest, patches covering ‘boils’ on the leg, one bare foot and one in a straw sandal.

Over the years, I encountered this pilgrim three or four times, here during the Tiger God Festival in Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Music during parades

Each palanquin is followed by worshippers on foot, and a pick-up with musicians, playing traditional music on drums, gongs, cymbals, flutes, clarinets, and string instruments – all contributing to a veritable cacophony. In present-day parades, music is sometimes delivered by ghetto blasters, playing techno music or other modern sounds, full volume, while sparsely clad girls dance to the music. Daoism is indeed a very tolerant religion, in which almost everything new is accepted.

Musicians, performing during the Boat Burning Festival (see below), celebrated in Jiading, near Kaoshiung. They play flutes, cymbals, a traditional 2-stringed instrument, named er-hu, a small clarinet-like instrument, and even a small guitar. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Musicians, playing gongs and clarinets, pass through fireworks during the Mazu Festival, Pitou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Equilibrist drummers, performing during the Lantern Festival, Taitung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blowing horns during festivals, Donggang (top), Pitou (centre), and Siao Liouchou Island. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Small boy – large drum, Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man is beating a gong with a drum stick, whose tip is wrapped in red cloth, Dongshih, south-western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mazu Festival

During the annual Mazu Festival, which is usually celebrated in April, thousands of pilgrims walk along a route, many kilometres long. The route is determined by the goddess herself, i.e. by priests ‘throwing the sticks’ in front of her image – two small concave wooden items that repeatedly have to land in a special way to determine the outcome of the question.

During the Mazu festival, a palanquin with an image of the Mother Goddess is carried along the route, from temple to temple, in this case in the town of Pitou. To receive the blessings of the goddess, people lie down in a long row, so that the palanquin will pass over them. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This pilgrim and his dog in Pitou are both well prepared for their long hike during the Mazu Festival. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Participants in the Mazu pilgrimage bow to receive her blessings in front of the Mazu Temple in Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the Mazu parade, these women, carrying colourful banners, bow to Mazu at a temple in Pitou. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Elderly pilgrim, participating in the Mazu Festival, Wangchien. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lantern Festival

This annual festival is celebrated during Chinese New Year. Thousands of paper lanterns are produced, and well-wishing words are painted on them, after which they are released into the air, with a bundle of burning fake money inside.

During this festival, volunteers undress to represent Handan-yeh, the Money God. As he dislikes cold, people shell the volunteer with firecrackers to heat him up, thus maybe winning his favour. The volunteers wear glasses, a hat or a helmet, and a scarf over their mouth and nose, to protect their face, but their naked body is often burned in numerous places.

Well-wishing words are painted on paper lanterns, after which they are released into the air, with a bundle of burning fake money inside. – Xiluo (upper 2), and Changhua. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Processions in honour of the money god Handan-yeh take place in the morning as well as in the evening, here in the city of Taitung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Boat Burning Festival

Until recently, this spectacular festival was celebrated in certain fishing communities in southern Taiwan. Prior to the festival, a complete, elaborately adorned wooden boat is built, only to be burned as an offering to Wang-yeh, the God of Diseases, hoping that he will spare the people of the plague and other dreadful diseases. In former times, the burning boat was pushed out to sea, ceremonially carrying the diseases away, but in later years, this practice was abandoned, and the boat was burned on land.

The pictures below were taken in 2007 in the village of Jiading, near Kaohsiung.

Before the burning of the boat takes place, people donate offerings of fake paper money to Wang-yeh, throwing bundles of them on board the boat. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Burning the boat. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

On the island of Siao Liouchou, southern Taiwan, the practice of burning a boat during the Boat Burning Festival has also been abandoned. Instead, fishermen place an image of Wang-yeh, or another local god, on board their vessel, whereupon they circumnavigate the island, hoping that this will suffice. Lots of fireworks are ignited during this circumnavigation.

I was invited on board this fishing vessel, which circumnavigated Siao Liouchou Island, bringing an image of a local deity on board. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

During the Boat Burning Festival, people on Siao Liouchou carry countless palanquins, containing images of local gods, to the beach to perform a ritual cleaning of the palanquin and its image in the sea water. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Tiger God Festival

The pictures below were taken during the Tiger God Festival, celebrated in the town of Shingang.

These men are spreading out long strings of fireworks in a street. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fireworks explode around palanquins, carried in procession. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This man has had his share of smoke from the fireworks! (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

A palanquin with images of the Tiger God and his generals is carried in procession. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Fireworks explode around the palanquin with the Tiger God and his generals. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dragon dance and lion dance

During Daoist festivals, so-called dragon dances and lion dances often take place in front of the temples. A dragon dance is performed by many men, who, with the help of poles, move a long piece of cloth, to which is attached a dragon’s head. The moving cloth and head create the perfect illusion of the writhing body of a dragon.

As a rule, a lion dance is performed by two men, hidden under a gaily coloured cloth, which acts as the body of the lion, whereas a lion mask is held by the man in front. During a more acrobatic form of lion dance, two men, hidden beneath a lion cloth, jump between small metal plates, placed on poles, often rather high.

Dragon dance, performed during the Lantern Festival, Taitung. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion dance, performed in front of the Fushing Temple, Xiluo (top), and in front of the Samlong Temple, Siao Liouchou Island. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Lion dance, performed during the Mazu Festival, Shingang. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Acrobatic lion dance on poles during the Mazu Festival, Shingang. (Photos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Chinese New Year

The pictures below show celebration of Chinese New Year 2015, in the town of Xiluo.

Shortly before midnight, thousands of balloons are released into the air from the courtyard in the Fushing Temple, dedicated to the Mother Goddess Mazu. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

People carry torches, consisting of green bamboo sticks with rolls of burning paper inside, from the temple through the streets of the town, hereby scaring away evil spirits. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

As a rule, entrances to Daoist temples are only closed once a year, about two hours before midnight on New Year’s Eve. They will be re-opened at midnight, marking the start of the new year.

In this picture, people are waiting for the doors of the Fushing Temple to be re-opened. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Daoist legends

Naturally, Daoist legends and stories about heros abound.

The Pilgrimage to the West is a mythological novel by Wu Cheng-en (1500-1582), in which a Tang monk, Xuan-zang, travels to the Thunder Monastery in western China with his three disciples. Sun Wu-kong (‘Monkey’) wreaked havoc in heaven and was punished by the Buddha to remain under the Five Fingers Mountain for 500 years. When he was released by Xuan-zang, he accompanied the monk as his disciple in order to repent. Armed with a magic stick, he was able to perform miracles on the way. The other companions were Zhu Ba-jie (‘Pig’), who was armed with a rake-like weapon, and Sha Wu-jing, who was responsible for the luggage, transported on a horse.

Sun Wu-kong is variously regarded as a deity or a mythological figure.

These puppets, depicting Xuan-zang (the monk), Sun Wu-kong (‘Monkey’), Zhu Ba-jie (‘Pig’), and Sha Wu-jing (the servant), were photographed during a marionette performance by the Hsin Shing-Kuo Puppet Show, taking place in the town of Huwei, western Taiwan. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

This picture from the same performance shows a scene from The Pilgrimage to the West, in which Sun Wu-kong, assisted by a Heavenly Goddess, manages to kill a demon, who has abducted the monk. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Presumably, this wall painting in a Daoist temple in the town of Miri, Sarawak, Borneo, relates how a poor couple inadvertently has come across a treasure. (Photo copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Uploaded November 2016)

(Latest update February 2025)