Kaj Halberg - Skribent & fotograf

Rejser ‐ Landskaber ‐ Dyr og planter ‐ Mennesker

Blog: Alger

Algae range from one-celled microalgae like Chlorella, Prototheca, and Ochrophyta (diatoms) to multicellular forms, including the large seaweeds, of which the largest, the giant kelp (below), may grow up to 50 m long. The most complex freshwater forms are the Charophyta, a division of green algae, which includes Spirogyra and Charales (stoneworts).

Some species of algae form symbiotic relationships with other organisms, in which the alga supplies organic material to the host organism, which, in turn, provides protection to the alga. Examples of hosts are lichens, corals, and sea sponges.

Proliferate reproduction of these ‘algae’ often takes place late in the summer. They sometimes occur in huge masses, dying ponds and lakes a characteristic bluish-green colour, which is often an indication of pollution with phosphates and other fertilizers to a level that may constitute a health hazard.

The name stonewort stems from a layer of calcium carbonate, which over time may be encrusted on these plants.

The scientific name is derived from the Greek rhodon (‘rose’) and phyton (‘plant’), thus ‘rose-coloured plant’.

Attached to stones and rocks, the branched fronds of this plant may grow to 90 cm long and 2.5 cm wide. Along both sides of the prominent midrib are a number of almost globular air bladders.

Since 1811, this species has been a source of iodine, utilized to treat goitre, a swelling of the thyroid gland, caused by lack of iodine.

It is restricted to the northern Atlantic Ocean, from Svalbard southwards to Portugal, in eastern Greenland and southwards to the north-eastern coasts of North America.

In Ireland, where this species is known as dúlamán, it was collected for food during famines. A local folk song, Dúlamán, describes a growing relationship between two people who collect the seaweed as a profession.

The generic name is derived from the Greek Nereis (originally a sea god, but in Latin meaning a mermaid), and cystis (‘bladder’), thus ‘mermaid’s bladder’. The specific name was applied in honour of German-Russian navigator, geographer, and Arctic explorer Friedrich Benjamin Graf von Lütke (1797-1882), in Russia known as Fyodor Petrovich Litke.

Elsewhere, however, this tree has been planted extensively, especially in Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Kenya, South Africa, and the island of Tristan da Cunha.

Indian, or Himalayan, horsechestnut (Aesculus indica) is common in the western parts of the Himalaya at elevations between 900 and 3,000 m, from Kashmir eastwards to western Nepal.

In parts of northern India, the leaves are used as cattle fodder, and the seeds are dried and ground into a bitter flour, called tattawakher. The bitterness is removed by thoroughly rinsing the flour, which is often mixed with wheat flour to make chapatis, and also halwa (sweet cakes). During hunger periods, a type of porridge, called dalia, is made from it. This species is also utilized in traditional medicine for a number of ailments, including skin problems, rheumatism, and headache. (Source: N.P. Manandhar 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. Timber Press)

The floating leaf is of a white waterlily (Nymphaea alba), whose leaves are usually various shades of green, but for some reason this leaf has turned orange-yellow. This gorgeous plant has a very wide distribution, found in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Temperate Asia, eastwards to Kashmir, northern India. In America, it is replaced by the very similar fragrant waterlily (N. odorata), which is also widely distributed, from northern Canada through the United States, Mexico, and Central America to northern South America.

The green stems in the foreground are common spike-rush (Eleocharis palustris).

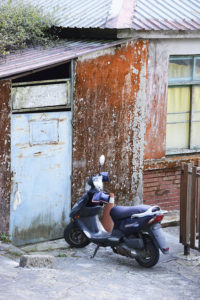

Orange alger vokser på en mur, Alishan National Forest, Taiwan. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Denne lille pige leger med grønalgen søsalat (Ulva lactuca), som hun har placeret på sit hoved, Langeland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brunalgen Pelvetia canaliculata, voksende på en stenet kyst, Loch Hourn, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Alger er betegnelsen på en stor og divers gruppe af organismer, hvoraf hovedparten er vandlevende og autotropiske, dvs. de producerer organisk materiale ved hjælp af fotosyntese eller gennem uorganisk kemisk reaktion. Mange former mangler de fleste af de celle- og vævsstrukturer, som er karakteristiske for typiske landplanter.

Alger rangerer fra encellede mikroalger, såsom Chlorella, Prototheca og Ochrophyta (diatoméer), til flercellede former, heriblandt de store brunalger, hvoraf den største, kæmpetang (nedenfor), kan blive op til 50 m lang. De mest komplekse ferskvandsformer er Charophyta, en underafdeling af grønalger, der omfatter bl.a. Spirogyra og Charales (kransnålalger).

Nogle typer alger danner symbiotisk samliv med andre organismer, hvor algen forsyner værten med organisk stof, mens værten til gengæld beskytter algen. Nogle eksempler på værter er laver, koraller og havsvampe.

Cyanobakterier (Cyanophyceae)

Disse organismer, populært kaldt for blågrønalger, lever mest i ferskvand og danner energi gennem fotosyntese. Deres navn stammer fra deres farve, afledt af græsk kyanos (‘blå’). Nutidens botanikere betragter ikke disse organismer som alger, men jeg inkluderer dem alligevel her på grund af deres folkelige navn.

Større forekomster af disse ‘alger’, kaldt alge-opblomstring eller vandblomst, finder ofte sted i sensommeren. De forekommer til tider i sådanne mængder, at overfladen på damme og mindre søer antager en karakteristisk blålig-grøn farve. Dette er ofte tegn på forurening med fosfater og anden gødning af et sådant omfang, at det kan udgøre en sundhedsrisiko.

Denne hun af gråand (Anas platyrhynchos) svømmer rundt i en ‘suppe’ af blågrønalger, Skanderborg Sø. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grønalger (Chlorophyta og Streptophyta)

Denne kæmpestore og forskelligartede gruppe af alger rummer mellem 9000 og 12.000 arter. Begge videnskabelige navne er afledt af græsk, chloros (‘grøn’), phyton (‘plante’) og strepto (‘snoet’), hvoraf sidstnævnte hentyder til morfologien af de hanlige sporer hos nogle af medlemmerne.

Grønalger (Chaetomorpha), skyllet i land på klipper, som er dækket af tangarten Pelvetia canaliculata, Loch Hourn, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Mønstre i grønalger, som vokser i et forurenet vandløb, Taichung, Taiwan. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grønalger vokser på eroderede kystklipper, Montaña de Oro State Park, Californien. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grønne og orange alger på denne våde klippe i en park i Taichung, Taiwan, danner omridset af en søvnig dinosaur. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Denne indtørrede øregople, også kaldt vandmand, af arten Aurelia aurita, hænger fast på en opskyllet planke, som er bevokset med grønalger, naturreservatet Vorsø, Horsens Fjord. Goplen kan minde om et trist rumvæsen. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kransnålalger (Charophyceae)

Kransnålalger er en gruppe af grønalger med over 400 arter verden rundt, hvoraf langt de fleste vokser i ferskvand, enkelte i brakvand. De er stærkt forgrenede, op til 1,2 m lange og producerer energi gennem fotosyntese.

I Danmark findes 5 slægter med 25 arter, der kan danne store bevoksninger i rene søer og damme, men skygges bort af planteplankton i tilfælde af øget eutrofiering. Navnet kransnålalge skyldes de kransstillede sideskud.

En ung Jens Gregersen med kransnålalger, Tåstrup Sø, Østjylland, august 1971. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rødalger (Rhodophyta)

En af de ældste algegrupper, der omfatter over 7000 arter, hvoraf langt de fleste er marine alger, bl.a. mange markante tangarter. Rødalger forekommer derimod sjældent i ferskvand.

Det videnskabelige navn er afledt af græsk rhodon (‘rose’) og phyton (‘plante’), altså ‘rosenfarvede planter’.

‘Suppe’ af trådformede rødalger, Kap Det Gode Håb, Sydafrika. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Brunalger (Phaeophyceae)

En meget stor gruppe af store alger, omfattende mellem 1500 og 2000 arter, deriblandt mange arter i køligt vand på den nordlige halvkugle. I daglig tale kaldes brunalger ofte for tang. Nogle medlemmer af gruppen spises af mennesker, især i Fjernøsten.

Uidentificeret brunalge, Hermanus, Sydafrika. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

En stor brunalge, skyllet i land nær Algeciras, Spanien. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Disse rugende hunner af ederfugl (Somateria mollissima) er godt camoufleret i opskyllet tang, Mågeøerne, Fyn. (Fotos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Disse afrikanske strandskader (Haematopus moquini) falder godt sammen med mørk tang, som vokser på strandsten, Muizenberg, nær Cape Town, Sydafrika. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hvor skarven (Phalacrocorax carbo ssp. sinensis) yngler på jorden, bygger den ofte høje reder af opskyllet tang, der, når den er stivnet, udgør et stabilt fundament for reden. – Mågeøerne, Fyn (øverst), samt Svanegrund, nær Endelave. (Fotos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Skarverne slæber ofte grønne planter til deres rede. – Svanegrund. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Unger af skarv i en tangrede, Mågeøerne. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Rede af sølvmåge (Larus argentatus) med to unger og et æg, Svanegrund. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Kæmpetang (Macrocystis pyrifera)

Denne art er den største af alle alger, som kan blive op til 50 m lang og er i stand til at vokse op til 60 cm om dagen. Den danner tætte bevoksninger langs Stillehavskysten fra det sydøstlige Alaska mod syd til Baja California, og den findes tillige langs kysterne af det sydlige Sydamerika, Sydafrika, Australien og New Zealand.

Denne kæmpetang, som er adskillige etager høj, blev fotograferet i Monterey Akvarium, Californien. Andre billeder fra dette fantastiske akvarium kan ses på siderne Hyldest til farven blå, samt Hyldest til farven rød. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dette eksemplar af kæmpetang blev skyllet op på Melkbosstrand, nær Cape Town, Sydafrika, og er nu delvis dækket af sand. I baggrunden ses Taffelbjerget. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Blæretang (Fucus vesiculosus)

Denne art findes langs Atlanterhavets kyster i Europa, mod øst til det nordlige Rusland samt Østersøen, endvidere i Marokko, omkring de Kanariske Øer, Madeira og Azorerne, samt fra Grønland og det østlige Canada mod syd til North Carolina.

De grenede stængler, som kan blive op til 90 cm lange og 2,5 cm brede, er fastgjort til sten eller klipper. Langs begge sider af den markante midterrib findes et antal næsten kugleformede luftblærer, som har givet navn til arten.

Siden 1811 har blæretang været en kilde til jod, som anvendes til bekæmpelse af struma, en opsvulmning af skjoldbruskkirtlen, der skyldes jodmangel.

Blæretang, Loch Hourn, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Buletang (Ascophyllum nodosum)

Bladene hos denne art, den eneste i slægten Ascophyllum, bliver op til 2 m lange. De er olivengrønne eller olivenbrune, uden midterrib, og har ægformede luftblærer (‘buler’) med regelmæssige mellemrum.

Arten er begrænset til den nordlige del af Atlanterhavet, fra Svalbard mod syd til Portugal, samt langs Østgrønland og mod syd til de nordøstlige kyster af Nordamerika.

Buletang, Loch Hourn, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pelvetia canaliculata

Denne plante, det eneste medlem af slægten Pelvetia, vokser i tætte, grenede klynger, op til 15 cm lange. Bladene har en kanal på den ene side, en metode til at undgå udtørring ved lavvande. Arten er almindelig langs Europas Atlanterhavskyster, fra Island og Norge mod syd til Spanien og Portugal.

I Irland, hvor denne art kaldes for dúlamán, blev den førhen indsamlet som føde i hungerperioder. En lokal folkesang, Dúlamán, beskriver forholdet mellem to mennesker, der har indsamling af tangen som profession.

Klippekyst, dækket af Pelvetia canaliculata, Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Indre Hebrider, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Pelvetia canaliculata, Loch Hourn, Skotland. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Nereocystis luetkeana

Denne plante danner tætte bestande og udgør en vigtig del af tangskovene langs den amerikanske Stillehavskyst, fra Aleuterne mod syd til det sydlige Californien. Den sidder hæftet fast til sten og klipper og har en rørformet stængel op til 36 m lang, som ender i en tæt klynge af blade, der kan være op til 10 m lange og 15 cm brede.

Slægtsnavnet er afledt af græsk Nereis (oprindelig en havgud, men på latin ændret mening til ‘havfrue’), samt cystis (‘blære’), således ‘havfrue-blære’. Artsnavnet blev givet til ære for den tysk-russiske navigatør, geograf og arktiske opdagelsesrejsende Friedrich Benjamin Graf von Lütke (1797-1882), på russisk kaldt for Fyodor Petrovich Litke.

Opskyllede individer af Nereocystis luetkeana danner mønstre på en stenet strand, Salt Point State Park, Californien. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Gulalger (Xanthophyceae)

De fleste af disse alger lever i ferskvand, men nogle findes i havet, andre på land, hvor de ofte klynger sig til diverse objekter, mest i fugtige omgivelser. De varierer fra encellede flagellater til simple kolonier og trådagtige former. Deres nærmeste slægtninge synes at være brunalgerne.

Baishuei-terrasserne i Yunnan-provinsen, sydvestlige Kina, er et område med snehvid kalcium-bikarbonat, aflejret af vand, som siver ned over en skrænt, hvorved der gennem årtusinder er blevet dannet terrasser. Dette område er helligt for den stedlige Nakhi-befolkning, som er beskrevet på siden Folk: Kinesiske minoriteter.

Denne dam på Baishuei-terrasserne er fyldt med gule alger. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I den fugtmættede og mineralrige luft omkring Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area, New Zealand, er talrige træer og grene dækket af orangegule algebelægninger. (Fotos copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Det naturlige udbredelsesområde af Monterey-fyr (Pinus radiata) er begrænset til nogle få lokaliteter i Santa Cruz og San Luis Obispo Counties i det centrale Californien, samt to øer, Guadalupe og Cedros, der ligger ud for vestkysten af det nordlige Baja California, Mexico. I disse områder trues den alvorligt af en indslæbt svampeart, Fusarium circinatum.

Mange andre steder er arten blevet plantet i vid udstrækning, især i Australien, New Zealand, Spanien, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Kenya og Sydafrika, samt på øen Tristan da Cunha.

Stammen af denne Monterey-fyr (Pinus radiata) i Wai-O-Tapu Thermal Area er delvis dækket af orangegule alger. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Grøn frø (Pelophylax esculentus) i en tæt bevoksning af gulalger og vandranunkler (Ranunculus), Amager. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

I den fugtige luft i Mangapohue-kløften, New Zealand, har disse gulalger kunnet få fæste på trådvævet af et hegn. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Hestekastanjer, slægten Aesculus, er hjemmehørende i tempererede egne af den nordlige halvkugle, med én art i Europa, som i sin tid kun var vildtvoksende på Balkan, ca. 10 arter i Asien, samt 7 arter i Nordamerika. Europæisk hestekastanje (A. hippocastanum) er præsenteret på siden Planteliv: Gamle og store træer, mens en amerikansk art, californisk hestekastanje (A. californica), er omtalt på siden Planteliv: Flora i Sierra Nevada.

Indisk hestekastanje (A. indica), også kaldt Himalaya-hestekastanje, er almindelig i den vestlige del af Himalaya i højder mellem 900 og 3000 m, fra Kashmir mod øst til det vestlige Nepal. I dele af det nordlige Indien anvendes dens løv som kvægfoder, og frøene tørres og males til et bittert mel, kaldt tattawakher. Bitterstoffet fjernes ved at skylle melet gentagne gange, hvorefter det ofte blandes med hvedemel til fremstilling af chapati’er, og også halwa (søde kager). I hungerperioder fremstilles en slags grød, kaldt dalia, af melet. Arten anvendes også inden for folkemedicinen mod forskellige lidelser, deriblandt hudproblemer, rheumatisme og hovedpine. (Kilde: N.P. Manandhar 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. Timber Press)

Stammen af denne indiske hestekastanje i Great Himalayan Nationalpark, Himachal Pradesh, er delvis dækket af en gul alge. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dette Khmer-relief, som gengiver en hinduistisk gudinde eller en adelsdame, er delvis dækket af en orange alge. – Bayon, Angkor Thom, Cambodia. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Dammen på billedet herunder, beliggende i en klitsø på Fanø, er fyldt med en gullig alge.

Flydebladet i forgrunden er af hvid nøkkerose (Nymphaea alba), hvis blade normalt er forskellige afskygninger af grønt, men dette blad er af en eller anden grund blevet gullig-orange. Denne prægtige plante er vidt udbredt, idet den findes overalt i Europa, samt i Nordafrika, Mellemøsten og dele af tempererede egne af Asien, mod øst til Kashmir i Nordindien.

I Nordamerika erstattes den af den næsten identiske amerikansk hvid nøkkerose (N. odorata), som ligeledes har en meget stor udbredelse, fra det nordlige Canada gennem USA, Mexico og Mellemamerika til det nordlige Sydamerika. Mere om nøkkeroser kan læses på siden Planteliv: Planter i folketro og digtning, hvor der også findes billeder af adskillige arter.

De grønne stængler i forgrunden er almindelig sumpstrå (Eleocharis palustris).

(Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

Denne husmur i Alishan National Forest, Taiwan, har fået patina af en orange algeart, som vokser på den. (Foto copyright © by Kaj Halberg)

(Oprettet september 2021)